The value of imaginative, non-directed play in building young people’s capabilities and sense of their place in the world is an enduring theme in educational and social thought. But the conditions under which it thrives are easily overlooked.

Play, as the Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga argued in his landmark 1938 book Homo Ludens, is fundamental to the human condition. The right to play is inscribed in the 1989 UN convention on the rights of children, along with the right to freedom of expression, but young people’s right to construct their own playworld, to explore and experiment, is generally constrained. The insights of Friedrich Pestalozzi, Johann Fröbel, Maria Montessori, John Dewey and other early child-centred educational theorists — that learning is grounded in experience — seem increasingly challenged by intensive parenting and the wider apprehensions of a risk society.

These debates and concerns frame Joan Healey’s new book, The Cubbies, a joyous history of the adventure playground she helped establish in 1974 in Melbourne’s inner-suburban Fitzroy.

Healey grew up in nearby Westgarth. Like some of her contemporaries, she escaped what she saw as the conformity and predictability of 1950s Australia for more than a decade of wandering and working in North America and Europe. A job advertisement for a play leader in London’s counter-culture magazine Time Out led her to a vacant lot in Notting Hill that had been transformed into “a higgledy-piggledy forest of turrets and tyres, splashed wildly with paint, toppling over a wooden fence like a giant pumpkin plant, with kids clambering all over it.” Free to muck about however they wanted with whatever came to hand, the kids built forts and shelters, raced billy carts, played in mud, devised elaborate games, and generally relished the conditions. Returning to Melbourne, Healey resolved to establish a similar patch there.

The concept of an adventure playground is generally attributed to Carl Sorensen, a Danish landscape architect interested in creating opportunities for what Fröbel termed “natural play” in urban settings. The idea traded on the persistent contrast between the benefits of direct experiences of nature in rural areas and the corrosive environment of cities and, more recently, exposure to technology. Richard Louv’s immensely popular Last Child in the Woods (2005), diagnosing nature-deficit disorder in children, is a recent iteration.

Sorensen also argued that city children, like their rural counterparts, should become familiar with the use of tools and materials. In the late 1930s, working with local educationists, he set up a family and children’s park that rejected the functionalism of existing playgrounds in favour of providing materials for children to use in designing their own experiences.

Sorensen’s ideas crystallised further on seeing children playing in the rubble of buildings destroyed during the Nazi occupation of Denmark, and in 1943 he and play leader John Bertelsen set up a “junk playground” on a deserted patch in Emdrup, Copenhagen.

After a visit that year to Emdrup, British landscape architect Marjory Allen, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, took the concept to London, setting up the playground on the Notting Hill bomb site where Healey was later to work.

Sorensen and Bertelsen’s advocacy of skrammlog or “junkology” was not universally welcomed. Criticism focused on aesthetics, discipline and risk. Sorensen responded to aesthetic concerns by screening the Emdrup site from its surrounds with dense plantings. Marjory Allen headed off perceptions of disorder and delinquency with a clever rebadging of the sites as adventure playgrounds. A long-time child welfare campaigner, she had overseen a wartime project to refashion the building rubble from bombsites into children’s toys. But risk-averse officials objected to her proposal to turn the bombsites themselves over to children. Her devastating riposte: better a broken bone than a broken spirit.

The Fitzroy site Healey eyed for Australia’s first adventure playground was a large vacant space owned by the Victorian education department, bordered by the Fitzroy town hall, a police station, a Catholic church and school, a creche and, looming on the southern border, high-rise public housing towers. In different ways, the first four institutions all found fault with the new facility along the lines that Sorensen and Allen encountered. But it was the children living in the high-rise, mostly from newly arrived communities and all lacking space, materials and sometimes parental licence for self-directed play, that Healey set her sights on.

She was buoyed by the optimism of the 1970s. New and innovative federal and state government departments dealing with youth, community development and recreation suggested political and funding support. But the enterprise scraped along precariously for years, with Healey and two co-workers operating in a cycle of short-term funding requiring the seemingly endless preparation of grant applications and acquittals. It’s a burden familiar to many community workers, but Healey’s notes and observations at the time provided an archive from which she has drawn creatively for the book.

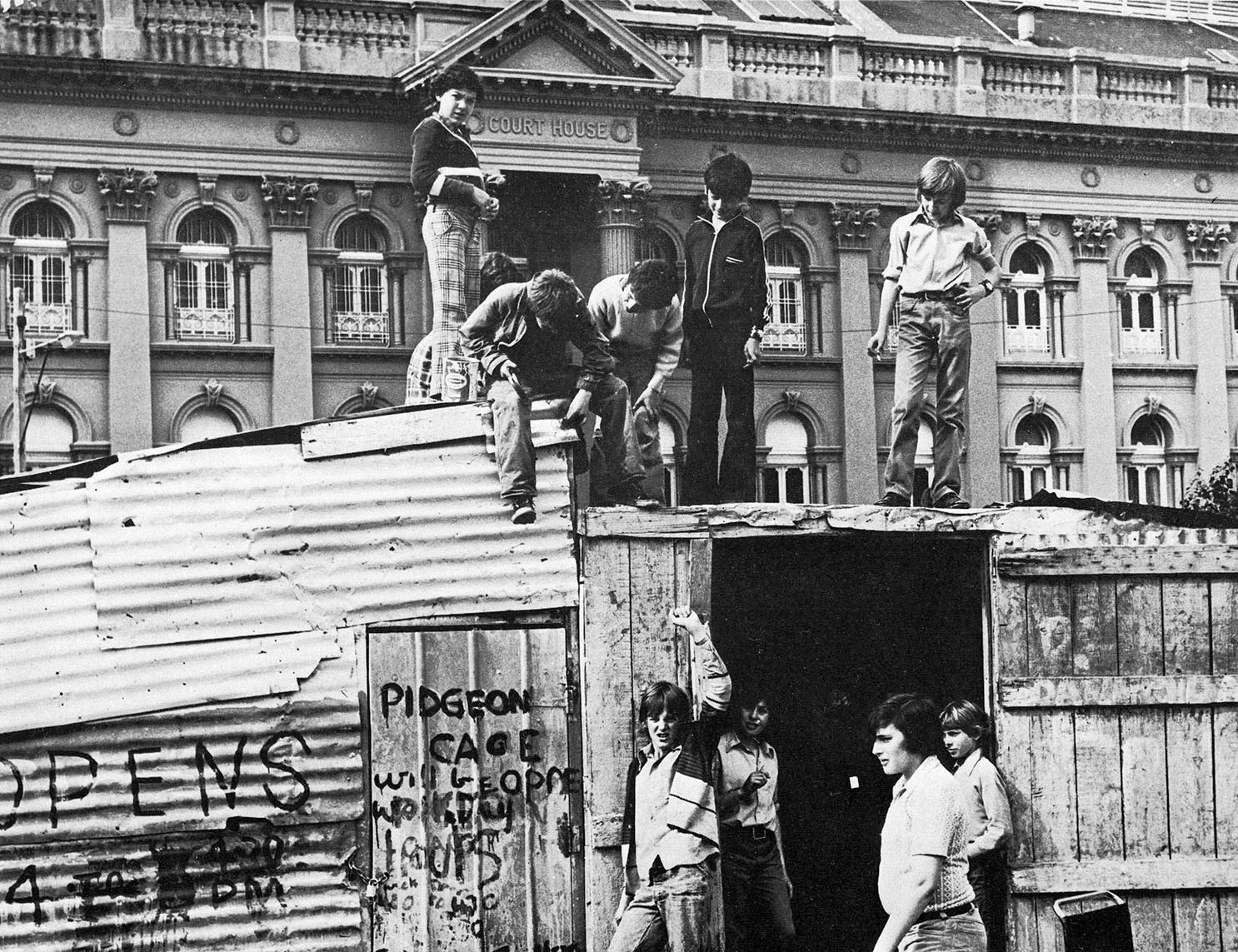

If funding agencies were sometimes reluctant to support the vision succinctly articulated by John Bertelsen — that children need places to play in, not to play on — young people embraced the idea enthusiastically. Instinctively, it seemed, they began to scrounge material to build the cubby houses that gave the site its name. Local business donated crates and pallets, old tyres, carpet scraps and more, the staff distributed basic hand tools, and the youthful building cooperatives, mostly comprising boys, set to work. Structures might last only a few days, but it was the experience not the product that mattered.

Instinctively, too, it seemed, the children began to dig garden plots and bring animals onto the site, applying their new construction skills to make guinea pig and rabbit hutches, chook pens, pigeon coops and more. Some animals feature as memorably in the book as the children. Lambchop, brought from a distant sheep farm, quickly adapted to rough-and-tumble inner-city life, surviving a kidnap attempt, developing a craving for discarded cigarette butts and creating mischief in a nativity play staged at the Catholic church. It became such a fixture that its profile featured on the Cubbies’ logo.

The building enterprise branched out further when young Jesus, from the high rise, set about constructing a sailing boat. One Sunday, the boat, its coat of paint still wet, was hoisted, mast upright, atop Healey’s tiny Austin sedan and driven across the city for its maiden voyage. The members of the Black Rock Yacht Club had surely never seen its like on the launch ramp, and everyone but Jesus, it seemed, was amazed when it floated.

Among these anecdotes, Healey’s discussion of the social and economic context in which the Cubbies operated underscores the challenges of community and youth work and the responsibilities and affective labour required of people in those roles. Healey writes movingly of the dilemmas that the social context posed for the free-play ethic: it was deliberately not instrumental, not aimed at “improving” children, but could their welfare needs be ignored?

As well as dealing with disputes and occasional bullying, Healey was aware of some children’s exposure to poverty, domestic violence and drug use, of the vulnerability of children home alone or locked out until late because their parents were working. Links were gradually forged with local community and health organisations, placing the Cubbies within an ecosystem of social care and lifting some of the burden from its staff.

The Cubbies survived an early attempt to close the place down. And the adventure playground concept soon spread, with at least four others established across inner Melbourne and more across Australia. At times, the concept had powerful supporters. Healey namechecks both the Fraser government’s social security minister Margaret Guilfoyle and the Hawke government’s deputy prime minister Lionel Bowen as two champions who rescued the project from financial precarity with longer-term funding.

Much of The Cubbies is voiced through the young people involved, and in doing so Healey recalls a vernacular of young Australia that now seems lost. Generations of children moving through the playground reflected waves of settlement — southern European, central and south American, Southeast Asian, African — but all, at least on Healey’s telling, were quick to pick up the playground argot. The pressure to transform the site, to minimise its supposed risk (Healey’s catalogue of injuries is remarkably slight) was ever a factor.

Still badged as an adventure playground, the Cubbies continues to operate on the original site. But like many of its counterparts, the ethic of self-direction and build-your-own has receded in favour of manufactured play structures and experiences. Things in Fitzroy, it seems, are not quite as grouse as they once were. •

The Cubbies: The Battle for Australia’s First Adventure Playground

By Joan Healey | Monash University Publishing | $36.99 | 288 pages