For many years Gordon Andrews was the most popular artist in Australia. We coveted his work with a passion; we spent our days pursuing it, and our nights dreaming about it. We sacrificed and scrimped to get more of it. Some of us even stole it. We couldn’t get enough of the stuff.

Though Andrews was hardly a household name, we all knew his most famous works: the Brown Bomber, the Sick Sheep, the Pink Snapper, the Blue Heeler, and the Red Lobster.

Gordon Andrews was, of course, the man who designed Australia’s banknotes when the nation shifted to decimal currency in February 1966. So appealing were they that the nation accepted them with alacrity, and soon bestowed upon them the greatest Australian compliment: nicknames. (And there were many of them. A Lobster – as the $20 bill is sometimes called – was also known as a Red Drinking Voucher on my teenaged Saturday nights.)

Banknotes are simply a portable means of exchange – pieces of paper representing a monetary value. They don’t have to be beautiful to do their job. The mighty US dollar, though exciting to possess in large quantities (I’m told), is famously dull to look at. But Andrews’s designs for our currency were positively pulchritudinous compared to the greenback. They were distinctive, modern and brightly coloured, and they told a more interesting narrative of our nation than we could reasonably have expected from a designer working in the early 1960s.

History is always an admixture of stories, and the tale of these designs, and how they came about, is blended with several others from postwar Australia. And though the story of Australia’s decimal banknotes is one of artistic accomplishment and acclaim, these other stories come down the darker road of our past. They’re about the theft of Indigenous art, a doomed criminal conspiracy, and a national business success story sadly drawn into corruption.

Should we be surprised? Isn’t money the root of all evil?

Australia had been thinking about decimalisation for a long time before it finally took the plunge. A House of Representatives Select Committee on coinage had first recommended that Australia go decimal in 1901; the 1937 royal commission on money and banking strongly favoured making the shift; and during the election campaign of 1958 prime minister Robert Menzies promised to ditch Australia’s pounds, shillings and pence for a simpler decimal currency. In 1959 Menzies’s treasurer, Harold Holt, convened a Decimal Currency Committee, and it soon endorsed the conclusion reached by all of the earlier inquiries: Australia needed to go decimal. Money calculations would be simpler; time would be saved at the cash register; school children would cease to be tortured by the complexities of the imperial system; and international trade would be made more efficient.

But what to call the new notes? Federal Labor MP Allan Fraser helpfully conducted his own competition, and some of the suggested names bear remembering: the Victa – after the lawnmower; the Billie – after the Little Digger; and the Eureka – after the tax revolt. Someone obsequiously proposed the Ming, in honour of the prime minister, who had acquired that nickname. In response, another citizen put forward the prosaic appellation Arthur – after Labor’s Arthur Calwell – but only if the new one cent coin was called the Ming, “because it takes one hundred Mings to equal one Arthur.”

Eventually a thousand possible names were submitted to Treasury. This voluminous list was whittled down to just seven for the Menzies cabinet to consider: Dollar, Royal, Crown, Austral, Pound, Regal and Tasman.

As if suddenly unnerved by the change it was contemplating, cabinet reached for the comforts of Empire. The new currency would be named the Royal, in honour of Australia’s unbreakable love for the monarchy. But strangely – it was 1963, after all – this caused an uproar.

Though Prince Philip had been in the country to open the 1962 Commonwealth Games in Perth a mere year before, the vast majority of Australians thought naming our currency in honour of his family a risible notion. As the president of that well-known left-wing organisation, the Chamber of Commerce told the Canberra Times, the use of the name Royal “over-emphasises, to the point of acute embarrassment, links and traditions which Australians appreciate and value but which they don’t like to advertise.”

Acutely embarrassed itself, cabinet backed down, and the idea was crumpled up and lobbed into the wastepaper basket of history.

Sense eventually prevailed and the new notes were christened Australian dollars. But what would they look like? Changing a currency is an economic reform, but it’s also a momentous cultural change. Would Australia get it right?

Now, committees have a bad reputation. Conventional wisdom asserts that a camel is a horse designed by a committee, and committees are traditionally where good ideas go to die.

Luckily, this isn’t always the case. The majestic King James version of the Bible, for example, was created by committee. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil…” Yes, a committee signed off on that.

In Australia we’ve had our share of camels born of committees, but the Currency Note Design Group, convened in 1963 by the governor of the Reserve Bank, H.C. “Nugget” Coombs, brought forth a Melbourne Cup winner.

When Coombs was putting together the committee, he asked Hal Missingham, director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, to recommend some Australian artists for the task. Missingham assured Coombs that he didn’t need painters, he needed graphic designers. “What the hell are they?” asked Coombs.

In the end he got one painter, Russell Drysdale, who acted as the Reserve Bank’s artistic adviser to the Design Group. The committee itself comprised seven individuals. Three of them – Missingham and the graphic designers Alistair Morrison and Douglas Annand – didn’t put pencil to paper, but acted as mentors to the others. It was these four – Richard Beck, George Hamori, Max Forbes and Gordon Andrews – who did the grunt work, labouring alone on their individual sketches. Despite the element of competition, the group evidently worked harmoniously. It was a panel of experts and Coombs expertly let them get on with it.

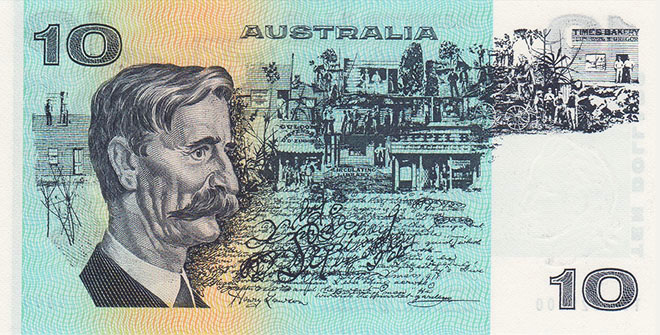

In April 1964 Andrews was declared the first among equals by his fellow designers. His design for the $1 bill featured a portrait of Australia’s head of state and some beautiful examples of Aboriginal art; the $2 note celebrated our agricultural traditions by featuring ruthless sheep baron John Macarthur on one side and the father of Australia’s wheat industry, agronomist William Farrer, on the other. The $10 bill coupled the convicted forger and colonial architect Francis Greenway with the writer, committed drinker and republican Henry Lawson. Clearly the Note Design Group wasn’t scared of ratbags – or complaints from wowsers either. The $20 bill celebrated the role of aviation in overthrowing the tyranny of distance by carrying portraits of the pioneer flyers Lawrence Hargrave and Sir Charles Kingsford Smith. (A $5 bill would be released in 1967. It managed to feature a woman – the humanitarian and advocate for migrants Caroline Chisholm – and the botanist Sir Joseph Banks.)

Designer currency: Australia’s first decimal banknotes, by Gordon Andrews.

They were all beautifully designed. They acknowledged the past and celebrated science and the arts. They didn’t take the easy route to popularity and acceptance; there were no soldiers or sporting heroes; there was no Don Bradman. Together they told a useful and unifying story: Australia was a serious place with some serious achievements; it had Indigenous people with a culture of their own; it was a constitutional monarchy – in other words, a democracy. Imagine if a similar committee were convened today. It would probably be staffed by shock jocks and News Limited columnists and we’d end up with an Anzac Tenner, a Phar Lap Fiver and a Don Bradman Century.

But even this highly effective committee didn’t get everything right. The $1 note was about to cause trouble for Nugget Coombs.

On one side of this note is a portrait of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, looking very regal, decked out in the Order of the Garter. The other side, by contrast, is adorned with three examples of Aboriginal art. In the top right are sticklike hunters – known as mimi figures – derived from the cave paintings of the Nalbidji people in western Arnhem Land. Below these figures are a kangaroo, a goanna and a snake, rendered in the x-ray style, also taken from the rock art of western Arnhem Land. These images are of unknown age and were first encountered by white Australia, in the form of anthropologist Charles Mountford, in 1948. The rest of the design is a copy of a bark painting from eastern Arnhem Land, which depicts the mourning rites of the Manharrnju clan.

There was just one small problem – the artist who produced this bark painting was very much alive. His name was David Malangi Daymirringu and he was a Yolngu man from Arnhem Land. Malangi had been a de facto member of the Currency Note Design Group but no one had thought to let him know his art had been used – or pay him.

When the story broke in the Adelaide Advertiser, Coombs – a man with a sincere and lifelong interest in the welfare of Australia’s Indigenous people – must have been mortified. He quickly gave instructions for Malangi to be recognised and compensated.

In 1967, after consulting with the artist, the Reserve Bank gave Malangi an engraved silver medallion – “To commemorate his contribution to the design of the Australian $1 note” – a fishing kit (including a tackle box) and $1000, which he used to buy a tinny with an outboard motor. (I like to think he was paid in cash with a bundle of the Brown Bombers he had unknowingly helped to design.)

Honour was served and justice – finally – done, and for the rest of his life Malangi was rightfully proud of his role in the design of the $1 bill. He continued to paint, and is now recognised as one of Australia’s greatest artists. In 1996 the Australian National University awarded him an honorary doctorate. He died in 1999, his place in our history assured.

So how did Malangi’s art make its way into Gordon Andrews’s design? There’s a story that Harold Holt – or another of Menzies’s ministers, William McMahon, or both of them – had seen the work in a French museum and recommended its use in the new design; but that version appears to be apocryphal. The truth is a little more tortuous. As the historian David H. Bennett describes it in the journal Aboriginal History, a Hungarian art collector and anthropologist named Karel Kupka, who did indeed work for the Museum of Arts of Africa and Oceania in Paris, met Malangi on one of his many collecting trips to Northern Australia and acquired the bark painting. While still in Australia, Kupka gave a photo of the work to A.C. McPherson, secretary of the Reserve Bank, who in turn passed it on to the Design Group.

It was an embarrassing episode but much good came of it. The mistake – and its rectification – is commonly credited with kicking off the debate about copyright law and Aboriginal art. It is harder today for Indigenous artists to be ripped off – in part because the Reserve Bank did the right thing fifty years ago. And let’s not forget that in the lead-up to the historic 1967 referendum just about every Australian of voting age was carrying around a little piece of Aboriginal culture. It couldn’t have hurt the cause of the Yes vote.

But the headaches weren’t over for Coombs. While he and the Note Design Group were basking in the success of a job well done, another group of determined and talented Australians were working just as hard to undermine their achievement. The full story emerged in 2012 when new evidence came into the hands of journalist Adam Shand.

Just before Christmas 1966, Jeff Mutton, a failed Melbourne milk bar owner, was at his local pub buying pots of beer – which sold in those days for the princely sum of twelve cents. He was using crisp new $10 bills. An astute observer might have noticed that Mutton pocketed the entire $9.88 change and then produced a fresh $10 bill to buy his next round.

Mutton was the ringleader of an audacious counterfeiting scheme and this was his first attempt at laundering the dodgy dough he had produced after almost a year’s labour. Can life get any better than this, he must have thought to himself, as he ordered another beer and trousered the change. Buried in his backyard in suburban Ashburton was a cache of nearly $800,000 worth of forged $10 bills – worth about $9.6 million in today’s money.

Mutton couldn’t have realised it at the time but this was the high point of his scheme. By the time he got home his life was in ruins. The police were there – ripping the house apart, searching for his hoard of fake cash.

Earlier that evening Mutton’s sister-in-law had purchased a box of chocolates for 65 cents at a corner store, innocently using a $10 bill supplied by her husband, Desmond, who didn’t tell her it was fake. Moira Mutton’s simple transaction was the beginning of the end for a criminal conspiracy that could have undermined the integrity of Australia’s new currency. A suspicious shop assistant didn’t like the feel of the bill and called the police. Fatefully for the gang of forgers, she also took down the licence plate number of Mrs Mutton’s car.

The Reserve Bank was shocked to discover that Mutton and his accomplices – Dale Andrew Code, a tailor; Ronald Keith Adam, a photographer; and artist Francis John Papworth – had used a run-of-the-mill colour offset printer and some freely available Strathbond No. 8 paper to create the forgeries. Despite the security features – a watermark of Captain Cook, a metal strip woven into the paper, and raised intaglio printing – a bunch of amateurs had been able to create a convincing facsimile of Australia’s new $10 note.

Adam, Code and Mutton were tried and convicted. Papworth gave evidence against his co-conspirators and was found not guilty. Mutton got ten years in Victoria’s French Island Prison. Several members of his family got short sentences or good behaviour bonds for using the notes. It was a triumph for the Victorian Police but a bitter reckoning for the Mutton family. If Mutton had put as much effort into his milk bar as he did into trying to defraud the Australian people, his business may never have failed.

Interestingly, the scheme was financed by one of Australia’s most notorious criminals, Robert Douglas Kidd. “Bertie” Kidd cracked open the safe of the Hampton Hotel in Brighton in order to finance the scheme. To make fake money you first need some of the real stuff. Kidd was charged over the affair, but incredibly he got off.

When news of the forgery hit the media, public distrust of $10 notes spread throughout Australia. Members of the Amalgamated Engineering Union even refused to accept them as part of their pay packets. Dud notes were still turning up in wallets and cash registers many years later.

Nugget Coombs decided he needed to take action to make sure this couldn’t happen again. He called in the CSIRO and commissioned it to come up with the world’s most secure banknote. At a meeting held in Thredbo in 1968, a young scientist called David Solomon first proposed making Australia’s currency from polymer.

Eventually the new notes created by CSIRO would be just about impossible to forge. They contained a see-through panel and a diffraction grating – “an optical component which splits and diffracts light into several beams.” Neither could they be reproduced by simply copying the note using state-of-the-art colour printing technology. They took a long time and many millions to develop, but by the bicentennial in 1988 Australia had released its revolutionary polymer banknotes, and created a new national industry along the way. And the first note off the printing presses was – you guessed it – a new $10 bill.

But the spirit of Jeff Mutton’s entrepreneurial criminality somehow proved infectious. The Reserve Bank set up two subsidiary companies – Securency International and Note Printing Australia – to develop and export the technology. In May 2009 two investigative journalists at the Age – Nick McKenzie and Richard Baker – revealed that Securency was involved in the bribery of foreign officials to gain contracts. Multimillion-dollar payments had allegedly been made into suspect tax-haven accounts. Evidence also emerged that some Note Printing Australia employees were up to no good. This complicated and ongoing scandal has unwound like a venomous snake in the heart of Australia’s supposedly staid central bank.

Eventually the $1 and $2 notes were withdrawn from circulation but, courtesy of inflation, we gained the $50 and $100 bills. Then the polymer notes arrived, featuring a new, all-star cast of Australian characters. More women – including Dame Mary Gilmore, Dame Nellie Melba and Mary Reibey – and just a single soldier, Sir John Monash. And still, thankfully, no sporting heroes.

Years went by, and the story of how Australia’s decimal currency came to be called the Dollar was largely forgotten. Then, more than half a century after public opinion had knocked cabinet’s decision in favour of the Royal on the head, a hapless prime minister decided it was a good time to reintroduce imperial honours. Not content with that, he decided to award one of the new gongs to the same member of the royal family who’d visited Australia when a name for the new currency was being debated. And the rest, as they say, is history. •