YOU MIGHT have heard some small explosions coming from Melbourne last week. Mostly, it was the sound of champagne corks popping, as supporters of an Australian Human Rights Act greeted the release of the much-awaited report of the National Human Rights Consultation. But not all the noise was in celebration; some of it might well have been the sound of blood vessels bursting among a group of disappointed Human Rights Act opponents.

Quite a crowd had gathered, under the impression that the attorney-general, Robert McClelland, would not only launch the report but also deliver the government’s response. Barely had he put off that decision (saying only that “the government will carefully consider all of the committee’s recommendations”) before the people with the burst blood vessels had “slammed” the report, to use the journalistic cliché. The chair of the consultation committee, Father Frank Brennan, came in for special criticism.

But what did the report say, and what are the prospects for change? The headline reform proposal was recommendation 18, which couldn’t have been clearer: “The committee recommends that Australia adopt a federal Human Rights Act.” While there are divergent views in the community on the merits of a Human Rights Act, the popular response was overwhelming. A total of 29,153 submissions – 83 per cent of those received – favoured this reform. Some concern was expressed that the ratio was skewed by successful campaigns to rally supporters of an Act. (The pro-Act side was led by Amnesty International and GetUp!. The opponents were led by the Australian Christian Lobby.)

To counter this concern, the committee commissioned independent opinion polling which showed 57 per cent of respondents supported an Act, 14 per cent opposed it and 30 per cent were neutral. Among those who had made up their minds, 80 per cent were in favour and 20 per cent opposed (figures rounded). The committee could only conclude that there was strong support for a Human Rights Act.

Introducing an Act would bring Australia in from the cold, as we are the only liberal democracy without some form of national human rights statute. But there is no universal template for human rights protection, so the Brennan committee had to choose from the many different models of human rights protection on offer.

Opponents of a Human Rights Act, meanwhile, warn that we should abandon the whole endeavour. After all, the human rights statutes in Zimbabwe and the Soviet Union didn’t exactly do the job in those countries. But there is an obvious response to this: the success of a human rights law – indeed any law at all – depends on a country’s having robust democratic institutions that adhere to the rule of law.

The committee opted for an approach known as the “dialogue model,” which is dominant in countries whose legal systems most resemble Australia’s, including the United Kingdom and New Zealand. This model – variants of which have already been adopted in Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory – would strike a very different balance from most constitutional bills of rights. For starters, it would not be constitutionally entrenched. The Australian Human Rights Act would be enacted and, crucially, could be amended by the ordinary parliamentary processes. So, for example, were it to contain a right that subsequently became anachronistic – as is arguably the case with the “right to bear arms” in the US Bill of Rights – parliament could simply amend the Act.

In the division of powers between parliament, the executive and the judiciary, parliament would remain the first among equals. This result is achieved by the interaction of two key provisions in the Act. The first is an “interpretative provision,” which says that laws should be interpreted compatibly with protected rights, subject to the express will of parliament. This means that the courts will attempt to interpret laws consistently with the rights set out in the Act, but cannot strain that interpretation beyond what parliament intended.

Sometimes a law will simply be incompatible with a particular human right. Where the High Court makes such a finding, it will only be able to issue a “declaration of incompatibility,” the second of the two key provisions. Rather than invalidating the law, such a declaration would simply notify parliament of the incompatibility. Parliament would then choose whether or not to amend the relevant law.

The Ghaidan case in Britain illustrates how this would work. The case centred on the Rent Act, which says that when a protected tenant dies, certain property rights are conferred on the tenant’s “surviving spouse” if the spouse had been living “as [the tenant’s] wife or husband.” The critical word is “as,” which must have been included to allow these property rights to extend not just to wives and husbands, but to people who were living in relationships like that of a wife and husband. If Westminster had wanted to confine this benefit to people who were recognised in law as a married couple, surely it would have opted for that simpler definition.

By the time of the Ghaidan case, it was uncontroversial to argue that the Rent Act extended to de facto heterosexual couples. The effect of the court’s decision was to extend the benefit to homosexual couples, because this interpretation allowed the Rent Act to operate consistently with the anti-discrimination principle and the right to private life.

Although there are some differences between the British interpretative provision and the Brennan committee’s proposal, we can expect that the Australian courts would use it in a broadly similar way. Essentially, such a provision encourages courts to interpret laws through a human rights filter, mitigating the unintended harshness that the law sometimes produces.

But the proposed Human Rights Act would also preserve parliament’s flexibility to impinge on human rights where appropriate. After all, there are many situations in which human rights conflict with each other. The law of defamation, for instance, seeks to balance freedom of expression and the right to protect one’s reputation.

Just as importantly, the proposed Act anticipates that there are some extreme situations in which certain rights must cede to other legitimate interests. There is a strong argument that effective anti-terrorism laws must sometimes impinge on rights such as freedom of association – albeit to the minimum extent necessary to protect Australia against terrorist attack.

During the consultation process, some concern was raised by former High Court judge Michael McHugh, among others, about whether some features of the UK version of the dialogue model would pass constitutional muster in Australia. Some of the heat of that debate was removed when a group of constitutional experts, including McHugh, agreed publicly that the key elements of the dialogue model could be incorporated into a carefully drafted Australian Act.

The report noted the committee’s cautious approach, with consideration only given to “those options that were constitutionally watertight.” The report annexes the advice of the solicitor-general, Stephen Gageler SC, which clearly affirms that the committee’s proposals are constitutionally sound.

WHILE THE PUNDITS have focused on the relationship between parliament and the judiciary under a Human Rights Act, in my view the really significant impact will be seen in the public service.

The Act would provide that “public authorities” must comply with protected rights. The term “public authority” refers principally to ministers, public servants, government departments and agencies. This means that when the government makes a decision, it must pay due attention to the human rights of anyone affected.

Significantly, the definition of “public authority” extends to private organisations performing functions on behalf of the government. This means that where the federal government outsources to a corporation the management of an immigration detention centre or a service on behalf of Centrelink, that corporation would be treated as if it were a public authority and it would be required to comply with the Act for this purpose. This prevents the government from contracting out of its human rights obligations.

But what happens where a public authority does breach someone’s human rights? The Brennan committee recognised the need for flexibility in allowing tribunals and courts to frame appropriate remedies. Often the best way of remedying a human rights breach is to require the relevant public authority to change its practices.

Usually where an individual’s human rights have been infringed, monetary compensation will be inadequate because it can do little, if anything, to restore the damage done to the individual’s dignity. For example, would compensation really salve the dignity of an individual who is unjustly denied the right to vote? And if so, how much?

Nevertheless, it remains an important remedy of last resort, and shows that we take human rights seriously. The law takes a similar approach in relation to defamation, where damages are frequently part of a court order in favour of a plaintiff. While it is generally accepted that a monetary award for defamation is an imperfect remedy, it still provides some relief to someone wrongly defamed and sends a warning to would-be defamers.

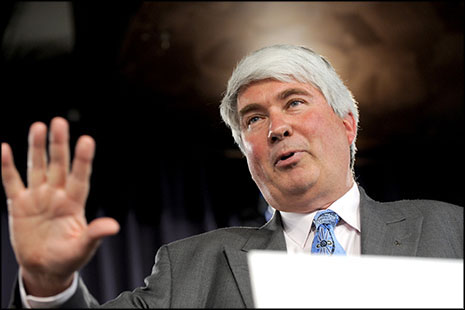

In spite of the popular support for an Act, the Brennan report frequently acknowledges that there remains a divergence of views in the community. Crucially, that divergence is most pronounced among politicians themselves, with shadow attorney-general George Brandis leading the opposition.

Recognising this, there is plenty of hard-headed pragmatism in the Brennan report. It makes a number of recommendations for reform that don’t assume a Human Rights Act is introduced. The report proposes major changes to the Acts Interpretation Act, for instance, which provides guidance to courts on how to interpret laws. It also proposes amending the legislation that guides public servants in their decision-making. The significance of these reforms is that they resemble key aspects of a Human Rights Act, and so provide the government with an option to pick and choose which features of such an Act it might want to introduce.

More broadly, the committee recommends fundamental changes to the way we learn about rights in Australia, and improvements in access to justice for disadvantaged people. Although the committee found great concern about the disparity in rights protection for Indigenous people, very few of its proposals are directed specifically towards Indigenous groups. For instance, the committee made no recommendation for the legal protection of the cultural rights of Indigenous people.

Many reports from large public inquiries are greeted with fanfare only to languish on a dusty Canberra bookshelf. But the size and scope of this inquiry – in terms of popular participation, it is the largest inquiry in Australia’s history – build momentum for human rights reform. That momentum is not all one way, and the vehemence of some criticism of the report highlights the fact that the government will have to be deft in building consensus if it decides to implement these recommendations. •