At a time when a special series on schools means for the Age “celebrating schools that achieve outstanding improvement in their VCE results over a decade”; when think tanks assume that to think about schooling is to pick a bite-sized “problem” or “issue” and offer a fix; when an agency with a $50 million grant from government offers the sovereign remedy of filling teachers’ heads with “gold standard” research so that their “practice” will be “evidence-based” — at such a time to see stablemates the Monthly and the Saturday Paper run series on the school system and its structural difficulties is a relief, albeit a mixed one.

The argument, put in a total of eight articles and two podcasts by three authors over several months, goes like this.

We have inherited a “two-track” public–private system from the sectarian conflicts of the nineteenth century. Funding such a system is bound to be a hot issue, and we are doing it particularly badly at the moment. The least needy students get more — a lot more — than those who need it most, and governments over-fund private schools while short-changing the public systems. The big losers, almost all of them in government schools, are “the disadvantaged.” A three-year gap exists between the educational attainments of the highest and lowest socioeconomic groups; kids who start behind stay behind because “nothing in our school system helps them catch up — in fact we put barriers in their way.”

Disadvantage goes hand in hand with social segregation. Thanks to the workings of “parental choice,” disadvantaged students are increasingly concentrated in disadvantaged schools — more so now than in any other OECD country. Public schools have been “residualised”; “privilege” and “disadvantage” are being entrenched. Australia’s high social mobility, supported by a strong system of school education is at risk. We need “mixing across the income distribution side,” the chair of the Productivity Commission is quoted as saying. “That seems to be really important for helping those from poorer backgrounds getting a leg up in life.”

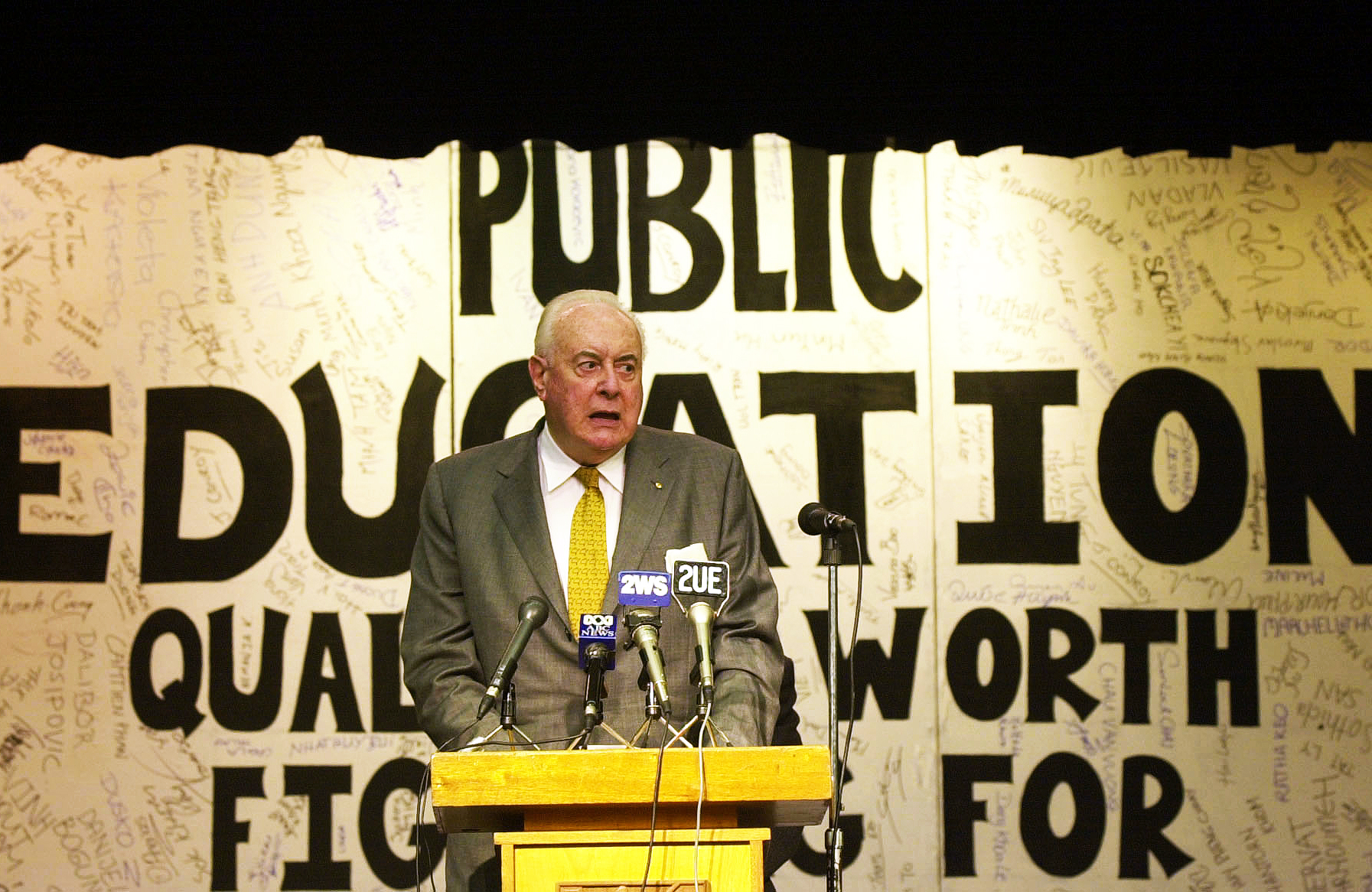

This “expensive and unproductive” schooling system is largely the doing of successive Coalition governments; Labor has tagged along behind, a mere “fellow traveller.” Fraser ‘lit the flame’ for an increase in funding for private schools but it was Howard and his education minister David Kemp who “fanned it into a bonfire.” They made choice “the central driver of education,” giving us “an ersatz voucher system.” In the face of all this Gonski “made a huge leap”; its failure was “tragic.” Labor in government has been intimidated by the religious lobby, by neoliberal shock jocks and by the Murdoch press. The task now is to level the sectoral playing field. Schools in receipt of public monies must accept greater public obligations; all schools should be funded in the same needs-based way irrespective of sector.

With the exception of the “segregation” argument and some specifics, this case will be familiar to most readers. It has been the basis of campaigning by and for public schools for at least thirty years.

But winning battles along the way hasn’t won the war, and here we are again in late 2024 with the feds locked in a bitter arm wrestle with the big states over who’s going to pay more for public schools. Getting more for public schools is urgent and important, but the problem behind the problem is to change the game. Gonski was not a “huge leap” in that direction; it proposed a first step. Its failure was a serious setback, but it was not “tragic.” On funding and much else a rethink is long overdue.

It’s not only the sectors

The public schools are indeed subverted by the sector system. The two non-government sectors feed off the increasingly “residualised” public schools because that’s the way the system is set up. The non-government schools have political leverage not available to the public schools — their parents pay fees, which means they can run scare campaigns about public funding: cut our grants and fees will go up!

Different funding sources compound the problem: non-government schools can spend whatever they can get their hands on from two levels of government, and from fees, philanthropy and investments. Particularly at the ever-expanding top end, they get their hands on a lot. Governments subsidise handsomely, but they have not demanded fee limits or spending caps in return. Government schools can spend no more than they get from governments; almost all try to supplement their income by charging de facto fees (what used to be called “voluntary contributions”) that can run to thousands of dollars, but the total collected is only a very small fraction of total government school revenues.

Then there’s real villain of the sector system, overlooked by the Monthly and the Saturday Paper: the regulatory gap between government and non-government schools, which particularly affects choice (by families) and selection (by schools). We do not have an ersatz voucher system that allows parents to take their voucher wherever they please. We have two systems, one of which includes some voucher-like features, the other its antithesis. It’s the existence of the two systems that does the damage: choice and selection are encouraged on one side, but prohibited (at least in theory) on the other. The rules are set up to encourage one-way traffic.

The public schools are indeed victims in all this but they are by no means innocent. Many government schools join in feeding off other government schools, in several ways: by design — the sizeable NSW selective high school system is the most offensive case in point, but the same kind of thing can be found on a smaller scale and other forms in most states and territories, often via “special focus” schools in areas such as music, the performing arts or sport. Zone dodging is a bigger problem — “out of zone” enrolments in one state (Victoria) account for something like four-in-ten government school enrolments.

The biggest problem of all is the real estate market. Parents can pay a one-off premium to buy a house in the zone of a “good” public school — that is, a school where they will find other students and families just like themselves without having to pay those onerous fees. Often seen as beyond the reach of policy, it isn’t. Governments could fund terrific schools in Mt Druitt or Elizabeth or Balga or Logan or Broadmeadows and the real estate market would soon get the message. That governments choose not to do so is as much a matter of public policy as the NSW selective high school system is. Levelling the playing field is, as the Monthly and the Saturday Paper say, the right idea. But there is much more levelling to be done than they realise.

Equality, social mobility and the grammar of schooling

Along with just about everyone else, the Monthly and the Saturday Paper assume that the point of more money is not just to help the public schools recover their self-respect but also to help them to do a better job of giving those from “poorer backgrounds” a leg up in life (as the head of the Productivity Commission put it) or, more ambitiously “to ensure that educational outcomes are not the result of differences in wealth, income, power or possessions” (as the Gonski panel put it). Opportunity should be equally available and its rewards should be equally distributed as between social groups.

No doubt equal opportunity and social mobility according to merit are good things in the wider society, or at least better than the alternative. But for kids? The long struggle by school systems to give every student an equal opportunity to develop and demonstrate merit has done terrible things to schooling and to many students. It has helped shape schooling as a kind of race track, a twelve-year competition for ranking within an entire cohort that becomes more and more explicit and intense as the moment approaches when students receive — and fail to receive — their ATAR (Australian Tertiary Admission Rank).

That “tyranny of merit,” as US philosopher Michael Sandel called it, is so familiar and so fundamental to many peoples’ experience and thinking about schools that is rarely noticed or remarked upon. Once it is taken for granted, other ideas follow: “educational outcomes” are and should be schools’ stock-in-trade; differences in outcomes are okay so long as they aren’t the result of differences in wealth, income, power or possessions; schools are there to give their students the best possible shot at success; systems should fund them so that the “disadvantaged” will do as well overall as “the advantaged.” With all this comes an even more fundamental assumption: the point of being at school is to get what comes after it.

Many schools — and especially schools catering to “the disadvantaged” that can’t rely on the “peer effects” available at “good” schools — do everything they can to help “the strugglers,” to get the kids to stay in the competition until they can’t or won’t, not necessarily because the schools want to do that but because that’s what the system requires and/or because the system provides no alternative.

To the extent that such efforts, sometimes bordering on the heroic, get more kids to read confidently, understand numbers and so on, that is an unqualified good thing. But when such efforts are fuelled by the campaign to give kids a leg up or to equalise the social distribution of “educational outcomes” — the competition thing — it’s not so straightforward.

One problem is that the language of “disadvantage,” “catch up” and so on is deaf to the effects of being a struggler or of starting behind and staying behind. Life in the “long tail” is no fun. Even the “extra help” — the “catch up tutoring,” the special coaching — can carry a deadly subtext. School is humiliating for many kids much of the time; their confidence is shot. That’s one reason why catch-up work is so difficult and why so many catch-up schemes, particularly at scale just don’t work.

Another complication: what is gained by one student or school or group is lost by another. The competition is a zero-sum game. What is a workable, even inspiring strategy for one student or family or school adds up to something entirely different over the system as a whole.

In Australia now and for many years around a fifth of students leave school before completing, another fifth last the distance but leave with no certificate or qualification to show for it, a further fifth get a certificate but a second-rate one of little use in making the transition to the next stage of life, and of the remaining two-fifths who get the coveted ATAR only half actually use it to get into a tertiary course. Trying to make this race a bit fairer, as the Monthly and the Saturday Paper (and the head of the Productivity Commission, and the Gonski panel) want to do, leaves the race intact; in fact it contributes to the media hype (vide the Age and its “celebration of schools that achieve outstanding improvement in their VCE results”), which is what keeps the race going. Working toward “equality” understood as a fairer distribution of success — and therefore of failure — is one thing; trying to provide twelve equally safe, happy and worthwhile years to every child and young person is quite another.

What the media (and the Productivity Commission) should be doing is getting themselves up to speed on the emerging alternative: organising each student’s work program around their intellectual progress (a larger and more important thing than mere “attainment,” by the way) and their progress in learning to learn, work in groups, communicate effectively and other such “general capabilities.”

In other words, the media and public agencies such as the Productivity Commission need to understand and help their audiences to understand what a different “grammar” of schooling — a different way of organising the work of learning and growing — might look like and why it’s needed. They should also be thinking about what schools are for, and whether the way of thinking and talking about schools that has driven educational policy since the Whitlam years is good for another fifty years.

It’s not all the Coalition’s fault

Labor hasn’t simply been a fellow-traveller in any important aspect of educational policy over the past half century or more; it has been the prime mover in several ways.

First, the structure of the sectors, including their funding and regulation, was designed by Whitlam’s Karmel committee in 1973 and installed by that government’s Schools Commission. “We created a situation unique in the democratic world,” said the principal author of the Karmel report, looking back on the arrangements it installed. Karmel’s system had “no rules about student selection and exclusion, no fee limitation, no shared governance, no public education accountability, no common curriculum requirements. We have now become,” she continued, “a kind of wonder at which people [in other countries] gape. The reaction is always ‘What an extraordinary situation.’” Successive Coalition governments have worked within this framework and taken advantage of its flaws to advance the interests of their constituencies in non-government schools.

Nor is “choice” the Coalition’s doing. It has been at the heart of Australian schooling since the early days of white settlement; the shift toward choosing as a consumer was well under way by the time Fraser came into office in 1975, and was intensified by Labor governments and their My School site.

Second, the philosophical basis of Karmel stemmed from the Fabians (including Karmel himself). From the days of R.H. Tawney’s Secondary Education for All (1922) and Equality (1931) equality has been the Fabians’ central goal, and schooling its key instrument. Tawney was representative of his generation in using “equality” to refer to the common dignity of all and to require the full entry of the working class into civil society and political life. But he also sponsored “equality of opportunity,” which in practice meant seeing that “bright” work class children (aka boys) would be able to “go on.” In the tumultuous construction of secondary education for all in the 1950s and 1960s the third of those meanings overwhelmed the first and second. (A careful reading of the Karmel report, by the way, will reveal its muffled protest against the degradation of a grand ideal).

The Rudd and Gillard governments completed the rout; their talk of “performance,” “accountability” and the like was among other things an attempt to whip schools into delivering more successes like themselves. The ideological substrate of the Monthly and the Saturday Paper is the Fabian tradition as fashioned by Labor governments in Canberra.

Labor was a prime mover of policy in a third area not mentioned by the Monthly or the Saturday Paper: it constructed a complicated and incompetent machinery for the governance of schooling, first in Whitlam–Karmel’s systematising of a national approach that embedded a second level of government — the federal government — in all three sectors in all six states (and now two territories). The Rudd–Gillard governments gave this approach its current institutional form including the National School Reform Agreements and a national system of surveillance of every school in the country.

The sector system and the grammar of schooling generate many of schooling’s problems; the governance system prevents their resolution. Only the first of these comes into the view of the Monthly and the Saturday Paper series, and then incompletely.

In one of its articles the Monthly draws almost in passing on Andy Mison, president of the national government school principals’ association. While we’re busy talking about Gonski, Mison is reported as saying, we’re not asking whether we’re going in the right direction or the wrong one. The accountability push has wasted a lot of time and energy in schools but it hasn’t delivered better education. As for Gonski, it only aimed at getting 80 per cent of kids up to the minimum standard in literacy and numeracy, scarcely an ambitious target. We need to start thinking about the design of schools and education systems, Mison continues. What do we want from them? From principals and teachers? Maybe it’s time to actually take a different approach. •