Ghetto at the Center of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong

By Gordon Mathews | University of Chicago Press | $29.95

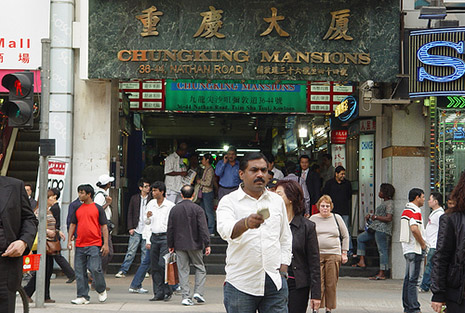

CHUNGKING Mansions, a down-at-heel complex of shops, guesthouses and restaurants in the heart of Hong Kong’s Tsim Sha Tsui district, is arguably the most infamous building in this 24/7 city. A second home to traders from across the developing world, it is a bustling zone of informal commerce. DVDs, appliances, garments, precious metals, medicines, books, mobile phones – almost anything can be bought here, off the books and in wholesale quantities. Entrepreneurs from across Africa, South Asia and the Middle East come to make their fortune, returning home with suitcases full of gadgets and gear.

Although most locals are put off by the building’s reputation for vice and the pushy touts who congregate outside, Chungking Mansions attracts a diverse mix of tourists, exiles and third-world traders. Asylum seekers find opportunities for work and for conversation in its labyrinthine corridors. European backpackers drop by for a taste of the demi-monde captured in Wong Kar Wai’s much-loved 1994 film Chungking Express. Others come seeking drugs, prostitutes or perhaps a curry at one of the excellent Indian restaurants. Chungking Mansions has something for everyone.

In Ghetto at the Center of the World – the first serious study of this remarkable building – anthropologist Gordon Mathews takes us deep into the lives of the people who live and work there. For Mathews, Chungking Mansions is more than a curiosity. As a hub of informal trade in Hong Kong’s turbo-capitalist present, it facilitates a specific kind of “low-end globalisation,” channelling untold quantities of goods, money and people around the globe, out of sight of the institutions of world trade. It is, he writes, “an alien island of the developing world lying in Hong Kong’s heart.”

Mathews’s study reads the global economy from the ground up. In 240-odd pages we learn of people smuggling gold across borders in their teeth, of Nepali Gurkhas selling heroin in back alleys, and of intricate systems for trading counterfeit and second-hand mobile phones. Mathews estimates that a fifth of Africa’s mobiles come from Chungking Mansions, and his analysis of how this trading system works is one of the most fascinating things I’ve read in a long time.

Mathews writes in an unadorned, no-nonsense style, with the intention of documenting – rather than celebrating or critiquing – the rhythms of this trading mecca. Based on several years of fieldwork, the book weaves together the stories of hundreds of store-holders, landlords, asylum seekers and workers interviewed by the author and his assistants. Edited interview transcripts with workers and residents lend rich ethnographic detail to Mathews’s arguments.

Some of these first-person accounts are very moving, detailing people’s attempts to make lives for themselves in an indifferent city. Mathews spends a lot of time discussing the fate of asylum seekers in Hong Kong, many of whom spend years – even decades – eking out a living in Chungking Mansions while waiting for their claims to be processed. Hong Kong’s lax visa policies mean that large numbers of people from Africa and South Asia can enter, but its asylum system is woefully inadequate at meeting their needs once they arrive. The cash-in-hand economy of Chungking Mansions often fills this gap.

Mathews's emphasis is firmly on the place, the people and the stories. Sometimes I wanted him to range a bit more widely, and to place these narratives into a broader analytical context. Mathews resists theorising, preferring to let the stories speak for themselves.

Perhaps this is a blessing in disguise. Amid all the loose talk about globalisation and neoliberalism that characterises contemporary academic debates, few writers have been able to provide better insights into how these processes play out at ground level. Anyone interested in the way our international economy actually functions will enjoy this marvellous book. •