IN THE EARLY HOURS of the morning a week or so before Christmas each year, students and principals in New South Wales begin logging onto the Board of Studies website to download those vital numbers which – fairly or otherwise – sum up twelve years of schooling. It’s an emotionally charged time. At one of the schools I taught in we used to have the Year 12 students back that morning to celebrate, commiserate, plot their university track – or discuss a last-minute change of career direction, which isn’t the end of the world and you really will like…

This is the time of year when newspapers inevitably focus on the schools that get the best exam results. In New South Wales the list of “top performing schools” includes the academically selective James Ruse High, the exclusive Sydney Grammar, and Peak Hill Central School in Central New South Wales. In Victoria the two selective government schools, MacRobertson Girls High and Melbourne High, usually top the list, followed in 2007 by a group of schools, mainly private, and another government school, Charlton College in north-west Victoria. In Queensland, Gin Gin State High School near Bundaberg isn’t far behind the state’s leaders.

Peak Hill Central School? Charlton College? Gin Gin High? For three years in a row Peak Hill Central has been one of half a dozen rural schools with over 6 per cent of its Higher School Certificate scaled exam marks in the highest band. Last year Charlton College had a Victorian Certificate of Education median study score of 35, well above most Victorian public and private schools. A very high percentage of students at Gin Gin State High School are offered tertiary places.

The sceptic might say that one or two bright kids could inflate the performance of these schools, which have a relatively small number of senior students. But many other rural schools also do very well in the Year 12 results. In New South Wales, schools in Bega, Eden, Condobolin, Dorrigo, Murrumburrah and Barraba do well, as do schools in tiny Barellan, Trundle and Tullibigeal. In Victoria the highest scoring state schools in 2007 included Wycheproof and Rainbow in remote western Victoria, and Mallacoota in the far east. The dozen or so state high schools in Queensland with a good proportion of high achievers regularly include Clermont, Cloncurry, Dalby, Kingaroy and Miles.

So does this mean that our best schools have gone bush? And what do we mean by “best” schools anyway? Are they schools where students achieve “top” results? If so, then what does it mean if these schools do little more than enrol the highest achieving students? Is a school less successful because a lower proportion of its students achieve high-end results? Do you measure success just in external exam scores?

Educators know that good teachers can make a difference to students. But school principals are also practical people: they know that the profile of a school is very much dependent on who walks in through the gates each day. So it might be safest simply to say that the schools mentioned in this article have a “high academic profile.” And it is certainly true that many of our more distant rural schools tend to have a better-than-average academic profile. Why is this the case, especially when the conventional wisdom is that kids in rural areas tend to fall behind?

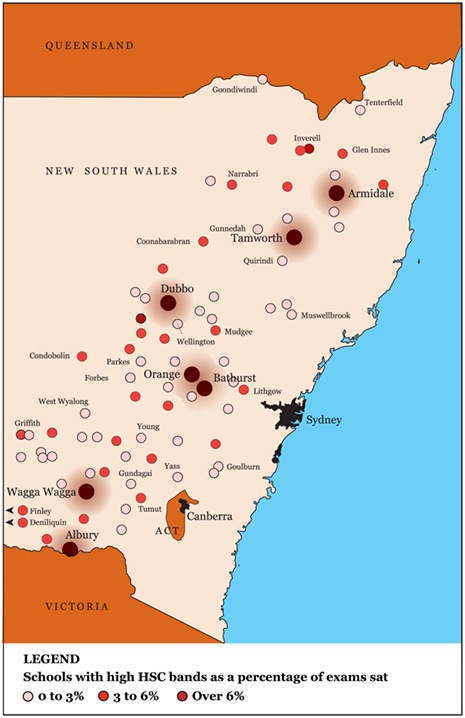

The map below shows how schools with a high academic profile weave a pattern through inland New South Wales. While there are obvious exceptions, the pattern is not completely random: each of the higher academic profile schools (the red and dark red dots) are a safe distance from the larger regional centres – places like Wagga, Orange, Dubbo, Tamworth and Armidale – with their bigger public schools and their growing number of private schools. It seems that many of these more remote rural schools retain the students who might otherwise be lured into bigger and brighter centres and schools.

This scenario is replicated in other eastern states. In Victoria the highest scoring rural state schools in 2007 were safely out of the way in the Wimmera–Mallee or in the most remote part of East Gippsland. Most of the dozen or so high profile state high schools in Queensland are located well away from large population centres and schools, including any seriously competing private school.

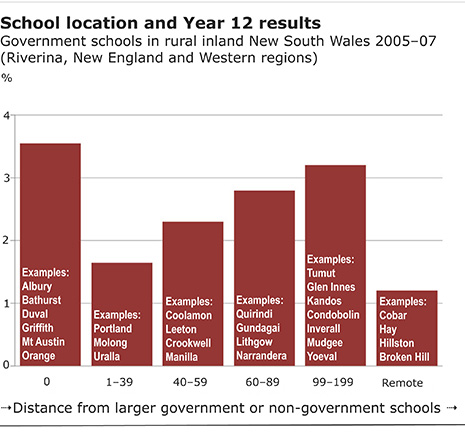

The chart below reinforces this point. Using NSW Board of Studies data it shows how the average Higher School Certificate scores of rural schools in three NSW regions increase the further they are located away from larger centres and larger competing schools. The HSC profile of the schools much closer to larger towns and competing schools is less impressive, as is the profile of schools in very remote locations. (Highest of all, of course, are the schools in the largest towns, which tend to draw in the best students from the surrounding areas.)

For the higher profile schools it seems that there is no necessary tyranny in distance – the problem is for those schools too close to their larger neighbours. This won’t be news to residents of small communities on the fringe of the big regional centres. These “sponge cities” across much of rural Australia have long soaked up many of the services of nearby towns and they are now drawing in their school kids as well. In New South Wales many of the schools in large regional centres stretching from Armidale to Albury have considerably inflated enrolments and reputations, derived in good measure from importing the best and brightest from the countryside, and from each other as well.

There is an irony in the fact that the schools that seem to hang onto their achieving kids are the ones that are relatively remote from the very competition that everyone seems to think is good for schools. The lack of competition seems to have preserved the academic profile of a significant number of these schools. They are in areas where most kids go, by default, to the local school – where the strugglers learn side-by-side with the achievers. It doesn’t mean that the more remote towns have better teachers or better facilities – they just enrol all or most of their local kids.

Obviously more than just distance is at work. The nature of the community has an impact on schools. School principals can be a critical factor – they send out distinct messages by what they say and do and by what they choose not to say and do – even more so in the bush. A school advantaged by location can still be let down by poor leadership. In some towns the picture is complicated by some limited competition between the public school and the usually smaller Catholic school. Patterns of schooling in rural Australia often go back generations, especially the preference amongst wealthier families for boarding schools in the cities. The distance factor is complicated by some commuting between adjoining towns, sometimes over state borders; schools just across the borders in parts of Queensland, Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory enrol a disproportionate number of NSW students, for example.

Despite all this, the evidence clearly shows a measurable academic bonus for most schools that have been anointed sole providers by an accident of geography. These mainly public (but sometimes Catholic) schools achieve remarkable things for their kids and families. Two of them are quite close together on the south coast of New South Wales, and so far they are resisting competition from new private schools.

DRIVING SOUTH from Sydney to Bega in the early 1960s – when I first made the trip – was a long and tortuous journey of over 400 kilometres, with a climax of hills, dales and hairpin bends. Travellers who eventually arrived at Bega could wind their way out to the coast at Tathra – a journey made longer, it was said, by the need to make the road stretch at least eleven miles from Bega so that the Tathra pub could keep its liquor licence. Or they might negotiate an even longer and winding road to Eden, the town whose changing fortunes from whales to woodchips seemed to embody remoteness itself.

It was the far south coast’s relative isolation that gave it a distinct character, largely untarnished by the growing summer invasions from Melbourne and the swarm of Canberra public servants flocking to the self-styled “Sapphire Coast”. As the holiday season ended these transients would head off home and the locals would resume their usual pattern of existence – a culture, which at the extreme end, would see the Bega Valley cast as the “deep south” of the state.

And remote it remained. Until the 1970s rural students attending Bega High still stayed in boarding houses in the town. Until recently, parents who wanted to exercise “choice in schooling” would have had to pack their kids off to a boarding school in a large town or the city. As a result, the public schools in and around Bega were, and still largely are, microcosms of the local area, as is often the case in rural Australia, enrolling kids from both sides of the tracks.

But if consistently high Year 12 scores are any guide, both Bega and Eden Marine High Schools are up there with the best non-selective schools in New South Wales. Over the last three years an average of six per cent of their Year 12 students could be called distinguished achievers, making the two schools stand-outs in rural NSW. One of Victoria’s remote high-profile schools, Mallacoota P-12 College, is just over the border.

The staff at these schools have plenty of stories of student success to tell. Jill Tourlass, principal of Bega High, mentions the students who topped the state in three HSC subjects in recent years. A parade of Bega students appears among the Education Minister’s Awards, scholarship lists, and among high achievers in creative arts and sporting. Eden Marine High recently ranked among the top three non-metropolitan public secondary schools in NSW. The principal, Brad Barker, is proud of the predominantly working class kids who do so well. Both schools run strong vocational education programs alongside their academic subjects, and the tracking of school leavers shows almost half of the students in both schools heading off to TAFE and university.

Distance may have protected these two schools in the past but there was never any guarantee that this would continue. Competition between schools increased with the establishment of a secondary campus of the Bega Valley Christian College in 1995. The area was also ripe for a Catholic school and Lumen Christi, one of the few new Catholic schools in New South Wales, was neatly dropped a few years ago into Pambula, a middle class area accessible to both Bega and Eden. The school has become a de-facto local school for Merimbula and Pambula and also draws in students from further afield.

So far, the impact on the two government schools has been muted. Bega Valley Christian College grew for a while but fell out of favour. It was recently taken over by the Anglican Schools Corporation, which renamed it Sapphire Coast Anglican College, and has not much more than a couple of dozen students at each year level. (Locals offer many reasons for the fall in enrolments. The school did not specifically respond to questions for the purpose of this article.) Bega High and Lumen Christi appear to have been the beneficiaries, with Lumen Christi’s enrolment growth almost a mirror image of the decline in the enrolments at the Christian College.

Paul Morris, one of the deputy principals at Bega High, isn’t under any illusions about what will happen in the event of a resurgence at the renamed Sapphire Coast Anglican College. One Bega High senior student has already been enticed to switch, complete with scholarship, and the private school has engaged in considerable marketing to make sure others follow. If it is going to grow, the Anglican school needs to get its enrolments from the Bega public schools – it has nowhere else to go.

While one rival was temporarily dispatched, Lumen Christi Catholic College proved to be more resilient, with enrolments growing since its first intake in 2001. Little clusters of Lumen Christi uniforms board the bus at stops along the Sapphire Coast Drive for the 50 minute journey to Pambula. The distance to school doesn’t worry Stan, father of two who catch the school bus each day. Stan told me that his kids started at Bega High when the family moved into the area, but now attend Lumen Christi. He says that the Bega school was all “fashion parades and fights,” and he wanted his kids to avoid the rough elements.

Lumen Christi parents aren’t necessarily Catholic or after any religion. In the unhappy recent tradition (as noted in August 2006 by Cardinal George Pell), Catholic schools draw their enrolments disproportionately from those better-off families who can afford fees, regardless of whether or not they are Catholic. The Catholic Bishops of NSW may have wrung their hands in anguish at the large numbers of non-Catholics in their schools, but schools like Lumen Christi need fee-payers of any faith, or no faith, to keep the books balanced.

In the process Lumen Christi has probably impacted more on Eden Marine High School than on Bega High. Eden has an interesting social mix, with a middle class layer on top of what has traditionally been a working class town. The bus heading north to Lumen Christi each day is unlikely to be carrying the full range of local kids. Like Bega High School, Eden Marine has a significant enrolment of Aboriginal kids, over 50, compared with less than a dozen at Lumen Christi. Joe Stewart, local Catholic and Aboriginal teachers’ aide at Eden, had his two kids at Lumen Christi, but they now happily attend Eden Marine. There were racism problems prior to the move but he supports the way the Catholic school handled the matter. The decision came down to the cost of enrolment. Brad Barker and his deputies remain upbeat about the success of Koori kids at Eden High, with ten currently in the senior years.

So what does the future hold for the public secondary schools on the far south coast? Any visitor to the two high schools can only be impressed by the level of energy in each school. Bega High’s Jill Tourlas makes every post a school promotion winning post. Both she and Pam Wellham, her predecessor, have successfully lobbied for upgrades of school facilities. The foyer of Eden Marine High is a parade of student achievement. Eden’s deputy principals, Linda Thurston and Bob Lind, have been genuinely impressed at the commitment of the staff. They point to the large numbers of teachers whose kids go to Eden Marine, despite an alternative being available. Parents at both Bega and Eden point to the diverse and relevant curriculum at the two public schools.

IT WOULD DO these two schools a disservice to claim that their high academic profile is simply because high achieving kids have had nowhere else to go. They don’t seem to take the competition for granted: all four deputy principals at the two schools are recent arrivals and know what has happened to public schools in other places. On the other hand there is a strong public education heritage in this area. Both Paul Morris and April Carter, president of the Bega High Parents and Citizens’ Association, commented on the high proportion of the local population with an active commitment to social inclusivity and public education.

In the face of competition the two schools are forming a mutually supportive relationship which extends to professional dialogue and sharing the burden of difficult kids, and will soon extend to sharing subjects and collaborating on more online learning. Together they are working with their feeder primary schools to form an enlarged learning community of schools, a trend which has had a successful track record elsewhere in New South Wales. They are also well aware of the issues which resonate in any parent community and have given judicious attention to discipline, uniforms, staff morale and school media exposure.

Eventually all the local schools will have to face the reality that, despite some population growth, the good citizens of the far south coast are ageing and aren’t having too many more children. As in so many other parts of Australia the area is becoming oversupplied with schools and overfed on the illusion of choice. If they survive, each school will probably invest an inordinate amount of energy to make sure it doesn’t end up on the bottom of the heap. In that competition the dice is always loaded against the inclusive schools.

Why does all this matter? Our robust and inclusive rural schools were the forerunners of comprehensive schooling across Australia. But for two decades we have been in rapid retreat from the idea that schools should serve all the students in each community. We have a new commitment to choice of schools – only our more remote and successful rural schools stand geographically defiant against such trends.

Schools have always been more than just places of learning. Schools which are inclusive have always been an essential core of democracy. That is why inclusive and free schools were established in the nineteenth century. Such schools not only serve the public – they create the public. They also help generate and sustain the social capital which creates successful and robust communities. None of this makes public schools immune from change, but we dismantle this structure at our own risk. •

The measures used in this article are all in the public domain. The NSW Board of Studies releases the names of students who achieve highest band results in each subject. The Sydney Daily Telegraph matches these against the number of HSC exams sat in each school. Queensland data shows the percentage of students in each school who receive an OP (Overall Position) between 1 and 15. About 80 per cent of all OP-eligible students in the 1–15 range are offered a tertiary place in Queensland. Such data, as well as VCE median study scores for Victoria, doesn’t allow interstate comparisons but it can show patterns within each state.

Chris Bonnor discusses this article on ABC Radio National’s Life Matters >