This is the text of the keynote address to the T.J. Ryan Foundation on 14 February 2017 by former NSW Education Department director-general and Gonski panellist Ken Boston

When I ran Britain’s Qualifications and Curriculum Authority during the first decade of this century, I reported to a secretary of state for education who was obsessed by the man on the Clapham omnibus: his acid test for any new proposal on curriculum, testing or qualifications was how it would be understood by this hypothetical, ordinary, reasonable and inevitably male commuter.

Given the number of middle-aged men in lycra pedalling to work in this city, I guess your local equivalent is the bloke on the Brisbane bikeway.

We presented the Gonski report to the federal government in December 2011. More than five years, four federal governments and two elections later, what, I wonder, does the bloke on the Brisbane bikeway understand about the report and what has happened as a result?

Like the man on the Clapham omnibus, his views will be drawn from newspapers, radio and television.

First, he almost certainly believes that the Gonski report said additional funding was the key to improving Australian education. Second, he probably believes that the Gillard and Rudd governments adopted Gonski by reaching “Gonski agreements” with the states, and promising additional “Gonski funding.”

Third, if he reads the Fairfax press, he will think that most of the problems facing Australian education will be solved if we get the last two years of “Gonski funding.” But fourth, if he reads the Murdoch press, he is likely to think that socioeconomic status has little bearing on educational outcomes, and that the differences between low-achieving and high-achieving schools are caused by poor teaching, inadequate curriculum, low standards, and lack of school autonomy.

Fifth, and regardless of which newspaper he reads, he believes that non-government schools save money for the government. And finally, he almost certainly believes that the two sides of politics are poles apart, and that no easy solution is in the offing.

I want to challenge these beliefs by explaining some of the thinking behind the Gonski report, going back to the government’s response, and answering some of the criticisms made of the report. Finally, I want to look at the post-Gonski realities of 2017.

Where, rather than how much

First, the Gonski report did not see additional funding as the key to improving Australian education. Its most critical recommendations were about the redistribution of existing funding to individual schools on the basis of measured need.

The report envisaged the amount allocated to independent schools being based on the measured need of each individual school, and the amounts allocated to Catholic and government systems being determined by the sum of the measured needs of the individual schools within each system – a process of building funding up from the bottom.

This is in sharp contrast to the process of the last forty years: top-down political negotiation by the federal government with state governments, independent school organisations, church leaders, teacher unions and others. The outcome has been that the funding allocations to independent schools, state Catholic education commissions and the state government systems are arrived at without any agreed and common system of assessing real need at the level of each individual school.

School funding has been, and continues to be, essentially based on a political settlement, sector-based and largely needs-blind. The Gonski report proposed that school funding be determined on an educational, not political, basis, sector-blind, entirely needs-based, and built up by aggregation of individual school needs from the bottom, not flowing down from the top.

Further, the report envisaged that, instead of a large part of this recurrent funding being spent in schools that don’t need it on things that matter little in terms of education outcomes, the strategically redistributed funding should be spent in schools that need it, and on the things that matter in the classroom.

We understood, of course, that funding is a means to an end, not an end in itself. In our final chapter, we set out some priorities for expenditure: quality teaching and school leadership, local deployment and management of resources, innovative approaches to teaching and learning, effective engagement with parents and the community, and quality assurance mechanisms. We were cognisant of the critical classroom factors for success, based on research by Michael Fullan, John Hattie and many others: instructional leadership by the principal and senior staff, diagnostic assessment, differentiated teaching, and tiered interventions to extend high-achieving students and support those falling behind.

We concluded that an additional $5 billion might be needed on top of the $39 billion then being spent annually by the state and federal governments, because of the commitment given by the federal government, after the review had started, that no school would lose a dollar as a result of the review. That was an albatross around our necks.

Education is a public good. Like other public goods, it is universally available, it has a cost, it is of benefit to all of us, and the benefit to each of us does not reduce the availability of the benefit to others. Teaching one child to read does not reduce the capacity of another child also to learn to read.

Our objective was to ensure that every child – regardless of language background, or family income and employment status, or ethnicity, or location and so on – should be given whatever support it takes to be, say, reading at minimum national standard by Year 3 (age eight).

Up to age eight, you learn to read: beyond that, you read to learn. If children are still sounding out the majority of words phonetically at age eleven or twelve, their comprehension is weak, their learning falls behind, and the chances are they will never fully recover.

Educational qualifications, on the other hand, are a positional good – an inherently scarce product, which confers an advantage. A Queensland Certificate of Education, a TAFE certificate, a degree, a higher degree – all are positional goods. We sought to ensure that educational achievement, as a positional good, is earned on the basis of talent and hard work alone, rather than purchased by those in a position of wealth and privilege.

In doing both things, we aimed to maximise Australia’s national stock of human capital, and to create a genuine meritocracy.

The bloke on the Brisbane bikeway almost certainly doesn’t appreciate that Gonski was a fundamental reimagining of Australian education within the framework of existing and available resources, not simply an argument for more resources for schools.

Labor’s version of Gonski

The second misunderstanding is that the Gillard and Rudd governments adopted Gonski, and then reached “Gonski agreements” with the states, promising additional “Gonski funding” over six years.

The Gillard and Rudd governments did not adopt the Gonski report, and neither has the current Labor opposition. The history is clear. The Gonski review recommended:

• That funding allocations for schools should be sector-blind and needs-based.

• That post-hoc equity programs, the most recent of which was New Partnerships funding, should be incorporated into the total needs-based funding.

• That the basis for the general recurrent funding for all students in all sectors should be a schooling resource standard for each school, set at a level at which it has been shown – in schools with minimal levels of educational disadvantage – that high performance is achievable over time.

• That the loading of funding for non-government schools as a proportion of average government school recurrent costs, or AGSRC, should cease. This is the mechanism that ensures that funding of non-government schools increases with increasing costs in the government sector, without measurement of need.

• That there should be loadings for the different elements of aggregated social disadvantage – English language proficiency, low socioeconomic status (broadly defined, which I will return to later), school size and location, and indigeneity – and we envisaged a further loading in due course for children with disability.

• That all government schools should continue to receive full public funding, and that this should be extended to a small number of non-government schools in areas where there is no government provision.

• That any additional public funding for other non-government schools should continue to be on a scale relating to parental capacity to pay, except that – in order to meet the government’s requirement that no school should lose a dollar – there should be a minimum level of public funding for all schools of between 20 and 25 per cent of the schooling resource standard, excluding loadings.

Finally, there was a major recommendation on process.

As a Commonwealth inquiry, we had developed a model that needed to be fully tested and refined with the states and the non-government sectors before implementation. We had proposed certain boundaries to the loadings for aggregated social disadvantage, but recognised that these had to be tested against hard data held by the states and non-government sectors.

We therefore proposed that a National Schools Resourcing Body, similar in concept to the former Schools Commission, owned jointly by all state and federal ministers and supported by an advisory group from all three sectors, should be established immediately to proceed with this necessary work.

What happened?

The Gillard and second Rudd governments buried the concept of a National Schools Resourcing Body, disallowing the possibility of a federal-state technical roundtable to test and develop the Gonski model.

The government drew up a National Education Reform Agreement to be agreed by COAG, under which government schools systems would receive funding, while non-government systems and schools would be funded under a National Plan for School Improvement.

This proposal allocated additional funding to all schools provided that the state governments (under the National Education Reform Agreement) and non-government schools and systems (under the National Plan for School Improvement) would undertake to apply the funding to projects approved under the headings of quality teaching, quality learning, empowered school leadership and meeting student need; to provide greater transparency and accountability to school communities; and to allocate funding according to the needs of their students.

Now, this was not what the Gonski review recommended.

• It was not sector-blind, needs-based funding.

• It continued to distinguish between government and non-government schools for funding purposes.

• It maintained the principle of the AGSRC, under which public funding for new places for children in disadvantaged government schools automatically generated public funding for non-government schools, without any consideration of disadvantage.

• And, although empowered school leadership, greater accountability, greater transparency and so on and are all worthy objectives, Gonski was about funding what happens in the classroom of each individual school – about money going through the school gate.

The National Education Reform Agreement and the National Plan for School Improvement contain needs-based loadings, but they are not founded on rigorous national, evidence-based testing of the school resourcing standard or the loadings and indexation. The Gonski panel envisaged that this would be done by a National Schools Resourcing Body on the basis of the needs of individual schools. As in the past, Labor’s agreements were negotiated top-down on a sector basis with the Association of Independent Schools, the National Catholic Education Commission, the Australian Education Union, and state treasuries.

This response to Gonski – which was far from implementing Gonski – was packaged as “Gonski agreements” and “Gonski funding.” These terms are now widely accepted by the public and the media as meaning that Labor (now in opposition) is committed to implementing the Gonski reforms.

That is not what the record shows. In government, Labor provided additional and very welcome funding for schools; in opposition, it has been an advocate for the so-called “last two years of Gonski funding”; and it declares a commitment to needs-based funding. But the Labor Party has not committed to sector-blind funding; it has retained the principle of the AGSRC; and it has not committed to total school funding being built from the bottom up according to measured need.

Labor delivered more money for education. But, like the Coalition government, Labor has ducked the fundamental issue of the relationship between aggregated social disadvantage and poor educational outcomes, and has turned its back on the development of an enduring funding system that is fair, transparent, financially sustainable and effective in promoting excellent outcomes for all Australian students.

Just two more years?

The third misunderstanding – the Fairfax view – is that most of the problems facing Australian education will be solved if we get the last two years of “Gonski funding.”

This funding was projected to flow over the six years 2014–19, with the bulk of the funding in the last two years. Substantial amounts are involved; the balance for 2018–19 is $4.5 billion across Australia. In contrast, the present federal government has allocated only $1.2 billion for the four years 2018–21.

Much has been achieved with the money received in the first four years. In every state, there are good examples of improvements in educational achievement as a result of the intelligent application of the funding to classroom practice. Every state minister has some anecdotes of success, and the Australian Education Union has produced a useful review of its impact in various places throughout the country. But there is no sign of a reversal of our national decline in educational performance. Unless we change the current top-down, sector-based, needs-blind funding system, and abolish the principle of the AGSRC, there will be a continually spiralling increase in the education budget without any lift in performance.

Providing the so-called “last two years of Gonski funding” will not deal with the fundamental problem facing Australian education. Neither side of politics is talking about the strategic redistribution of available funding to the things that matter in the schools that need it, on the basis of measuring the need of each individual school. And in the absence of a proposal for such redistribution, state ministers have no alternative but to clamour for additional funds.

Good money after bad?

I turn now to the view of the Murdoch press that Gonski was throwing good money after bad, that socioeconomic status has little bearing on educational outcomes, and that the difference between low-achieving and high-achieving schools is caused not by lack of funding but by poor teaching, inadequate curriculum, low standards, and lack of school autonomy.

The Gonski report was based on recognition of the causal relationship between aggregated social disadvantage and low educational achievement, as demonstrated nationally and internationally, not least in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, surveys of the impact of economic, social and cultural status on educational attainment.

There is no agreed definition of socioeconomic status in universal use in the literature. Parental socioeconomic status is a composite index that can be measured in a variety of ways. Precision is important because imprecision will reduce the observed association with achievement. Conclusions about the relationship with achievement are best based on studies that encompass the full range of socioeconomic status, because if the range is truncated (for example, to parental income alone) the measured association will appear less than the true association.

The main local commentator arguing that socioeconomic status is not that important for educational outcomes is Gary Marks, a researcher at the Australian Catholic University, who uses a very narrow definition of socioeconomic status. He defines it in terms of occupation, education and income, and – writing in the Australian recently – criticises the Gonski report on the grounds that “the ability to understand calculus, balance chemical equations, comprehend and make inferences from unseen text or write reasonable essays is not because a student’s father works as a bank manager rather than a bank teller, or because their mother has an arts degree rather than a TAFE qualification.”

Of course, Gonski never proposed that such fine distinctions as the difference between the children of a bank manager and the children of a bank teller matter educationally. We were concerned about aggregated social disadvantage, about children who experience some or many disadvantages: children who do not speak English, who have never been to school, who have been in the country for less than three years and (because their parents must look for work) are unlikely to remain in any particular school for more than two years, whose families are destitute, and whose mothers are illiterate even in their own language, rather than concerned about children suffering from the apparent liability of having a mother with a TAFE qualification.

I agree with Marks’s conclusion that the key driver of student achievement is student ability, that some children are born smarter than others, and that much of the variation in student achievement is genetic. But I do not believe that potential ability is restricted to the upper levels of the socioeconomic scale. The Gonski report was based on the premise that there is potentially similar latent cognitive ability among all three- and four-year old children about to start school, whether they be from a fourth-generation Australian family with an income three times the national average, or from a family that has been unemployed for three generations, or from a newly arrived refugee family speaking no English.

The measure of socioeconomic status used in most survey research is the Index of Economic, Social and Cultural Status, or ESCS, developed as part of PISA. This is much broader than the Marks measure; in addition to parental occupational status and parent educational attainment, it includes measures of home possessions relating to wealth, measures of educational resources, and measures of cultural possessions.

It is on that basis that the OECD constructs its familiar graphs showing the socio-educational gradients in PISA results for the thirty-five OECD countries, and their average. These demonstrate the relationship between low achievement and low economic, social and cultural status, the impact of which is greater in Australia than in similarly developed countries, greater than the OECD average, and becoming more so since measurement began at the start of this century.

The Gonski measure of aggregated social disadvantage is broader still: it includes the ESCS measure, but adds to it measures of English language proficiency, Indigeneity, and school size and location. For each of these we proposed a scale of loadings, to be tested by the National Schools Resourcing Body and added for each school to the base grant. This would provide the compound resources needed in disadvantaged schools to support such things as whole-school instructional leadership, teachers’ aides, counsellors, intervention programs, and home/school liaison personnel fluent in the dominant community languages.

Three other factors are commonly raised as alternative explanations for the low achievement of disadvantaged schools.

One is teacher quality. Are teachers in our disadvantaged and low-performing schools less skilled and imaginative than those in our more advantaged and higher-achieving schools?

The term “teacher quality” is a curious one. We never talk of doctor quality: we talk of the quality of healthcare. And the quality of healthcare varies greatly from place to place: the variation is explained not by the quality of the medical staff, but by their number, the availability of specialist diagnosis and treatment, and the availability of technical and ancillary support. Low-quality healthcare is explained by inadequate resourcing for the task at hand, not by the relative incompetence of the available doctors and nurses.

It is the same with teaching. The issue is not about teacher quality, but about the quality of education. The teachers in our most disadvantaged schools are at least as good as those in our most advantaged schools; the issue is not their competence, skill or commitment. The issue is that their number, resources and support are unequal to the task.

There are some ineffective teachers, just as there are incompetent doctors, but they can be found in schools both effective and ineffective, and there are procedures for dealing with them. Research has shown that there is greater variation in teacher quality within schools than between schools. I believe there is no correlation between teacher quality and school performance in Australia.

But the quality of education in disadvantaged schools is – with very few, although notable, exceptions – greatly inferior to that in schools serving advantaged communities.

The schools at the lower end of both the scale of aggregated social disadvantage and the scale of educational performance are the emergency wards of Australian education. In a hospital emergency ward, a battery of medical specialists and intervention techniques is targeted at the recovery of the individual.

A typical Australian suburban school serving a migrant community – more than 80 per cent of its children with a language background other than English, from at least ten different language groups, having been in the country less than three years and unlikely to stay more than two years in the school – is an emergency ward in the same real sense.

So, too, is a small rural school or school in a regional centre, taking children from the long-term unemployed, some suffering from foetal alcohol syndrome, many of whom have never been read to, or even held a book, or know that the pages are turned from right to left.

Hospitals save lives. Schools save futures. That image is not in the public mind. Children entering schools from backgrounds of aggregated social disadvantage require immediate diagnosis of need, and immediate intensive care if they are to be saved. They need smaller class sizes, specialist personnel to deliver the appropriate tiered interventions, speech therapists, counsellors, school/family liaison officers including interpreters, and a range of other support.

And that support requires money. You can’t deliver education as a genuine public good without strategically differentiated public funding directed at areas of need. That’s what Gonski sought to achieve.

The second factor commonly raised is the curriculum. Do our disadvantaged and underperforming schools provide a poorer curriculum than other schools?

If we think of curriculum as the sum of all the experiences the school provides for a child, both formal and informal, planned and incidental, then the answer is yes. Disadvantaged schools sadly lack the capacity to offer experiences such as outdoor education, instrumental music, drama classes, after-school sport, inter-school competition, clubs and societies, and within-school counselling services, with all the activities of the school being conducted in first-class indoor and outdoor facilities. Some of that provision would, of course, involve capital rather than recurrent funding. The Gonski report made very significant recommendations on capital funding and infrastructure, but these received no response from the federal government and were ignored by the media.

If curriculum is defined solely in terms of the subject content to be covered, the answer is no. The state curriculum authorities and the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority have set a robust and appropriate curriculum. Processes are in place to monitor its ongoing effectiveness and to change it as necessary.

The issue is not the curriculum itself, but enabling children to access the curriculum by getting their feet on the lowest rungs of the ladder, and then assisting them to climb steadily. And that is far more difficult in schools serving disadvantaged communities than elsewhere. Teaching a child who arrives at school without breakfast, or has had insufficient sleep because she is the main carer for her siblings, or has learnt English only in the last two years, or has been physically abused at home, requires rather more preparation, effort and resources – and hence funding – than teaching in a large, wealthy independent school where the majority of children, thankfully, are likely to have had a much better start in life.

The third common explanation for low school achievement is lack of school autonomy. Is this why some schools are underperforming and others are doing much better?

I don’t believe so. In England my organisation was responsible for the school curriculum, for qualifications, and for examinations and tests. This covered all schools, both the independent schools and the grant-maintained schools funded by government, which encompass all other schools including faith-based schools of all religions. We were responsible, among other things, for reporting to government on school outcomes – that is, providing the data from which the British media then construct the notorious “league tables.”

Maintained schools in England receive a block grant. They are run by elected school boards that have the power to hire and fire the head teacher, who in turn hires and fires the staff. Schools have considerable autonomy in the use of resources and in school organisation, including discretion within broad guidelines over the structure of staffing and their remuneration.

During my time, there was also a steady move towards the establishment of academies – independent schools endowed and run by philanthropists, but with matching money from government. These academies, the independent schools and the grant-maintained schools have levels of autonomy far greater than any government or Catholic school in Australia.

This degree of autonomy had absolutely no impact on the socio-educational gradient in England. Year after year, the grant-maintained schools in the whole of the north of England, and in the depressed areas in Essex and the west perform poorly, except in the more affluent parts of the large cities and towns. Those schools in the Home Counties around London are the highest-performing in the country. Despite their autonomy, it is aggregated social disadvantage that determines the outcome.

Greater autonomy is not the reason some schools perform better than others in Australia. High-performing non-government schools generally have much greater management (if not curriculum) autonomy than high-performing government schools, but the key factor in both sets of high-performing schools is generally that they serve affluent and educated communities, and are selective either academically or financially.

More autonomy for government schools in Australia would have no impact on the impact of the aggregated social disadvantage on educational performance. It does, however, have some benefits, the most important being that it shifts accountability for school management from compliance with inputs to the achievement of outcomes.

The Gonski report proposed that any school in receipt of public funds should be publicly accountable for the outcomes it achieved. We floated the concept of an external audit process, such as the Ofsted inspection model in England, and referred to the use in Queensland of the Teaching and Learning School Improvement Framework, the external audit process developed by the Australian Council for Educational Research.

President Ronald Reagan’s dictum, “trust, but verify” is the key to managing increased autonomy for schools in receipt of public funds. An independent, external quality-assurance agency, composed of highly skilled and experienced professionals, would provide schools, parents and governments with authoritative and sound assessments of school achievement – in both the cognitive and affective domains of learning, not just test scores – and identify areas for attention. In my view, such an approach would be beneficial in assisting all schools in Australia to achieve improved outcomes, as it has been in England.

Follow the money

That brings me to the fifth belief of the bloke on the bikeway, that non-government schools save the government money that otherwise would have to be spent on teaching the children who attend Catholic and independent schools.

This seems intuitive and logical. The Productivity Commission has estimated the amount received from governments by government schools in 2014 at around $12,085 per student, and by non-government schools $9262 per student. Education minister Simon Birmingham has put the non-government student figure at about 60 per cent of the government amount. The saving to governments is variously claimed to be anything between $4 billion and $9 billion per year.

In some very important work, Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd in two recent papers have given us the first evidence-based analysis of school recurrent income for all schools. From the My School website dataset for 2016, they took the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (or ICSEA, the mean value of which is around 1000) for each school, and the annual recurrent funding (which was for 2014, the latest available.) ICSEA is the best proxy currently available for the educational challenge facing each school.

With the advent of the My School website, we have access for the first time to disaggregated recurrent financial data for each individual school in the country, rather than averages and total figures for sectors and states. These data are on the public record, provided and authorised by the schools and the responsible authorities and systems.

Bonnor and Shepherd asked the question “What would be the recurrent funding cost to governments if they had to fully fund the education of all school students?” To answer this, they divided the My School dataset into nine ICSEA ranges from lowest to highest, totalled the government funding for government, Catholic and independent schools within each range, and calculated a funding rate per student. They thus had nine groupings of comparable schools serving similar communities, from which the funding for government, Catholic and independent schools could be compared.

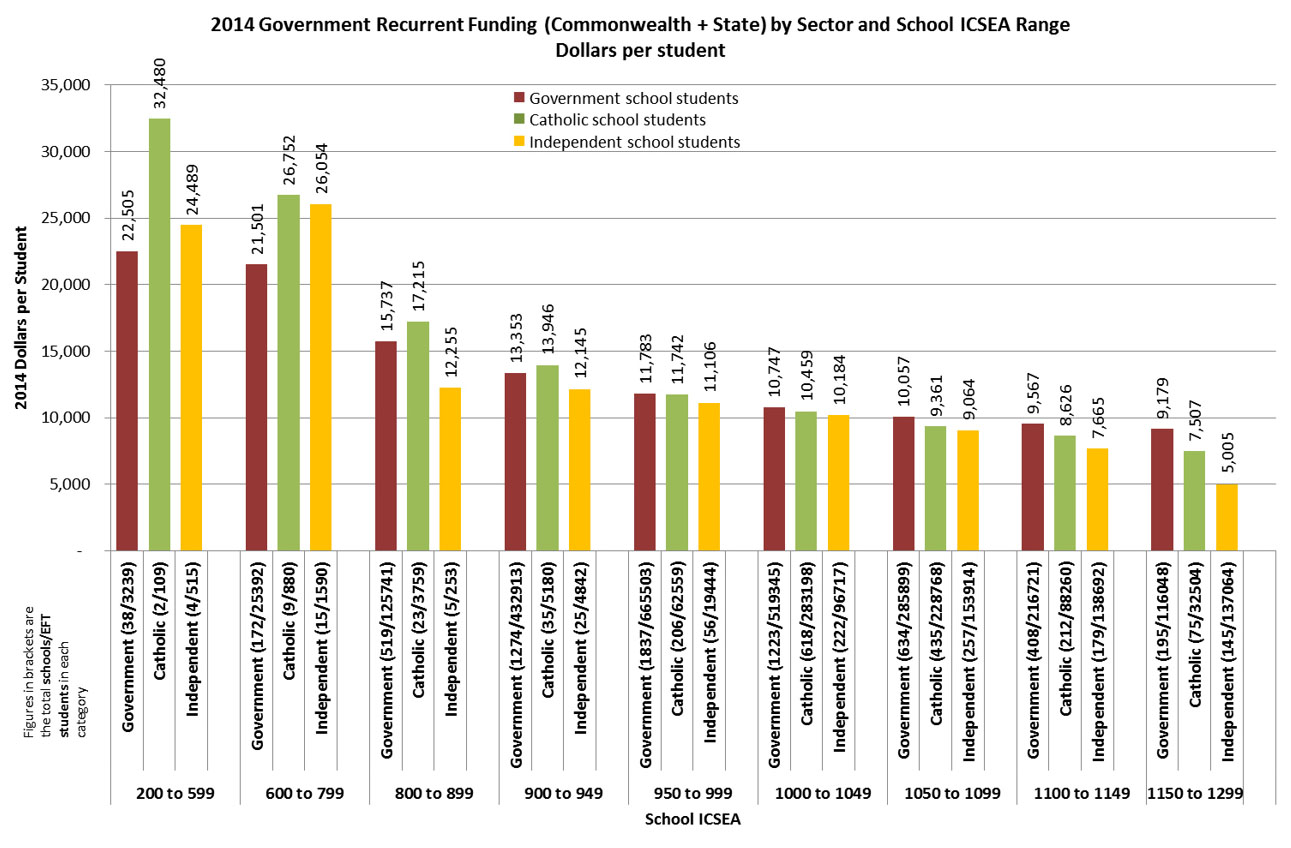

This is shown in Figure 1. The brackets below the graph are the number of schools and students in each category. As expected under the National Education Reform Agreement, higher rates of funding apply to the more disadvantaged schools. This is why people say the current system is needs-based, although as we will see, the reality is very different.

1. Government recurrent funding, Commonwealth and state, by sector and school ICSEA range, 2014

Source: Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd, “The Vanishing Private School.”

The distribution of the number of schools is important. The ICSEA range 950 to 1149 embraces 65 per cent of all schools, but 91 per cent of Catholic schools are within that range, and 79 per cent of independent schools.

You can see that the combined state and federal government dollars per student in each of the sub-ranges from 950 to 1149 are remarkably similar for each sector. The Catholic schools within this range receive between 90.8 per cent and 99.5 per cent of the public dollars going to public schools enrolling similar students, on top of which they charge fees. The 79 per cent of independent schools in this range receive between 79.5 per cent and 94.6 per cent of the amount for similar public schools, again before they impose fees.

On the basis of these data for all ICSEA categories, Bonnor and Shepherd conclude that if all students in the non-government sector were to transfer to the government sector, the recurrent cost to governments would be, at most, about $1.9 billion per year.

How can the large discrepancy between that figure and claims of up to $9 billion be explained? There are several factors.

The grossly inflated figure of up to $9 billion is what it would cost the governments to pick up the entire recurrent funding of non-government schools from all sources, including fees, which in some schools are more than $30,000 per annum. Clearly, this should not be factored into a calculation of what governments save by children attending non-government schools.

The Productivity Commission figures are averages. The use of averages in comparisons between government, Catholic and non-government schools assumes that each sector enrols identical students in terms of socio-educational background, and that they are distributed evenly along the ICSEA scale.

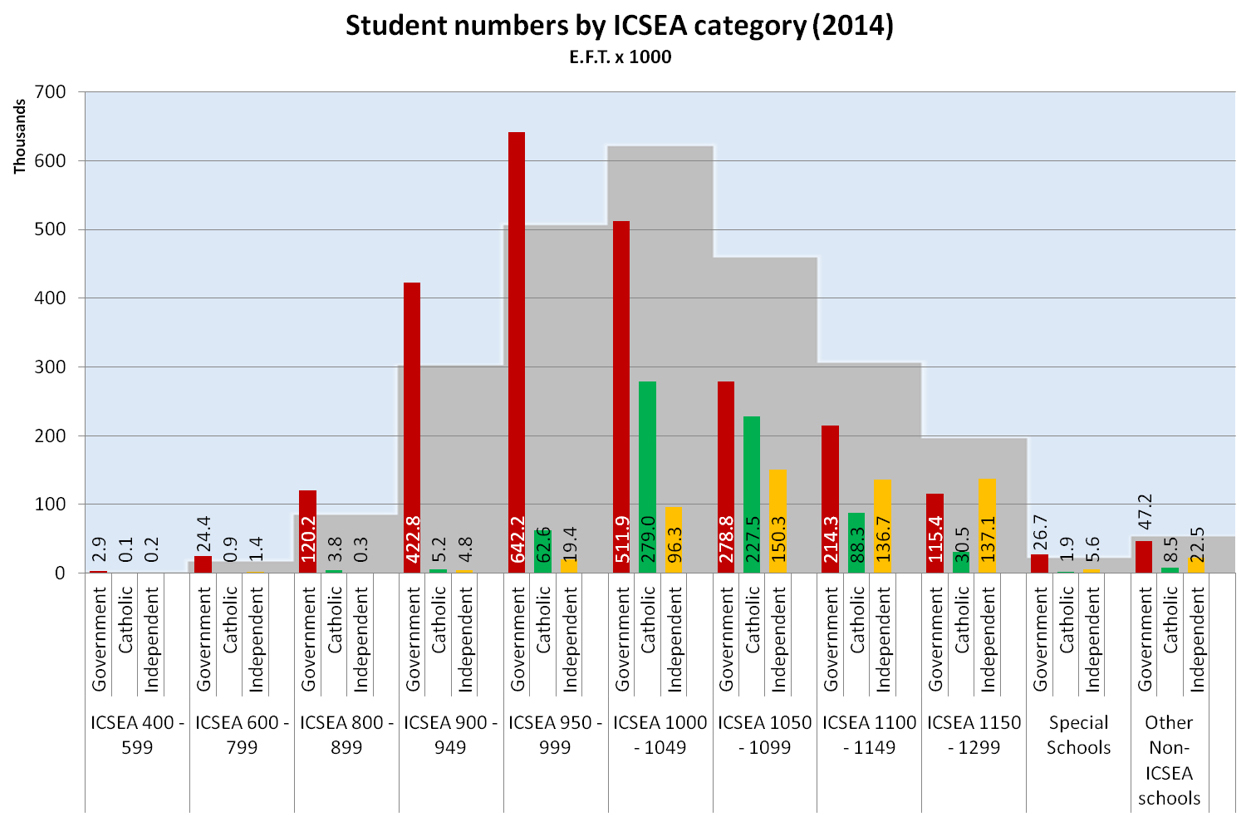

But they are not: they are students from measurably different backgrounds, and the three distributions are also very different. In Figure 2, the red, green and orange columns show student numbers in government, Catholic and independent schools; the grey area in the background illustrates the relative totals of students in each ICSEA range. The two columns of non-ICSEA schools on the right are there for the sake of completeness: they are special schools and remote schools, and are predominantly government schools.

2. Student numbers by ICSEA category

Source: Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd, Uneven Playing Field: The State of Australia’s Schools.

On the basis of the data in the figure, it can be seen that government schools enrol 52 per cent of their students from below the ICSEA mean of 1000, Catholic schools 11 per cent of their students, and independent schools just under 5 per cent. Forty-eight per cent of government school enrolments are above ICSEA 1000, compared to 89 per cent of Catholic school enrolments and 95 per cent for independent schools. Government schools enrol students from all socioeconomic levels; Catholic and independent schools have only insignificant numbers below ICSEA 950. This reflects not only socioeconomic factors, but also enrolment practices: government schools (except for selective high schools in some states) are open to all local students, while non-government schools have a range of enrolment discriminators, the most important being the charging of fees.

Further, consistent with government requirements, the Productivity Commission methodology for calculating these averages includes data on user cost of capital, depreciation, payroll tax and school transport for government schools, which are not added to the non-government numbers. None of these items provide funds for day-to-day use in teaching and learning. The result is that – despite warnings and caveats against the misinterpretation of data contained in the Productivity Commission reports and national reports on schooling, which are more often than not overlooked by commentators in their search for a preferred rationale – the reported funding of government schools is overstated by almost $5 billion, or 15 per cent.

There is one other important factor: over the period since the Gonski panel began its review, government funding (state plus federal) to government schools increased by an average of just under 3 per cent per annum, which is comparable with inflation. In the same period, government funding to non-government schools increased by around 6 per cent per annum, twice the rate to government schools and a figure well above inflation.

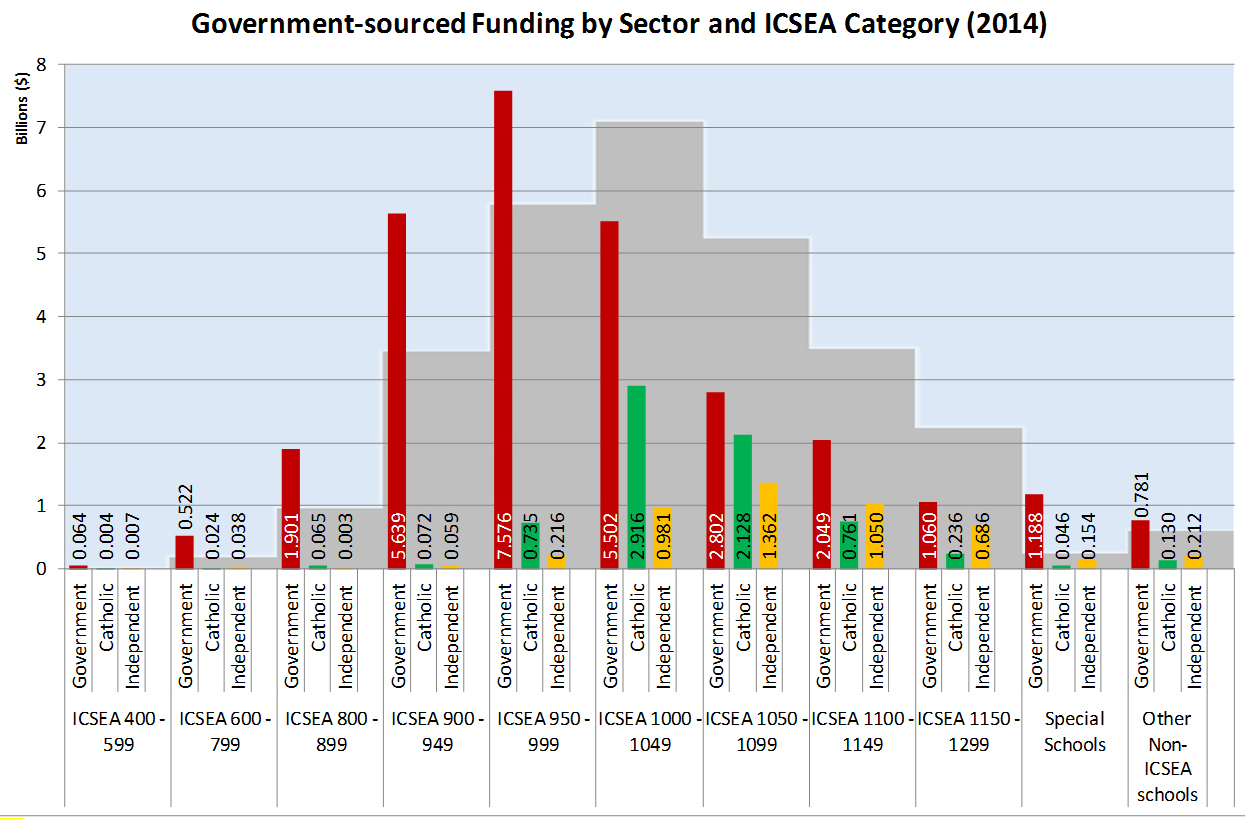

Five years after Gonski reported, the recurrent costs of the majority of non-government schools are essentially funded by governments. Figure 3 shows total government funding in each sector across the ICSEA range.

3. Government-sourced funding by sector and ICSEA category, 2014

The grey area in the background illustrates the relative totals of students in each range (not to scale)

Source: Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd, Uneven Playing Field: The State of Australia’s Schools.

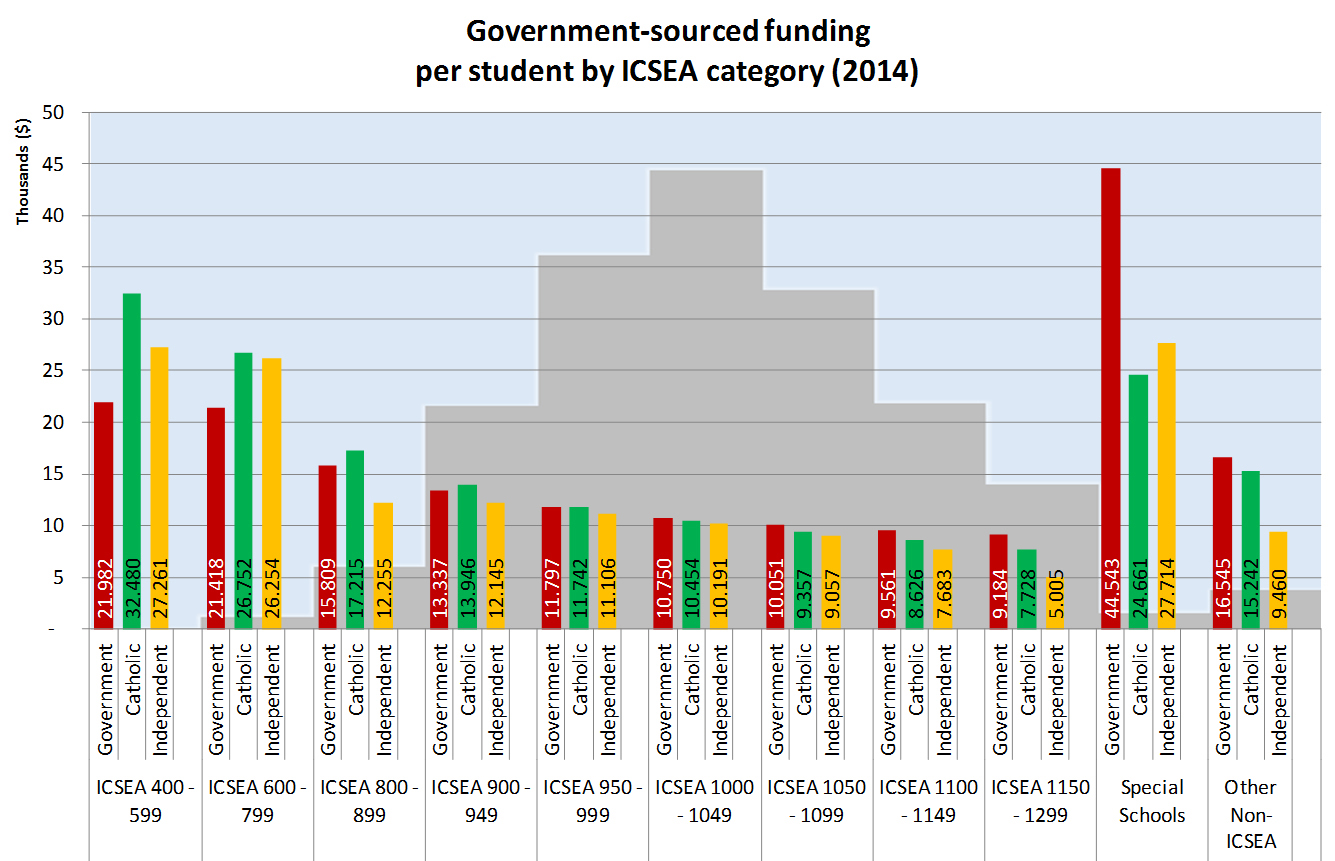

In Figure 4, Bonnor and Shepherd show government-sourced funding by ICSEA category. Below 800 ICSEA, non-government school students attract considerably more government funding than government school students. In Catholic schools, this situation persists through to ICSEA 1000: it is only in the 1050 range and above that government funding of Catholic schools falls noticeably below that of government schools.

4. Government-sourced funding per student by ICSEA category, 2014

The grey area in the background illustrates the relative totals of students in each range (not to scale)

Source: Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd, Uneven Playing Field: The State of Australia’s Schools.

With more than 91 per cent of Catholic schools receiving 90–99 per cent of the funding going to similar public schools, and 79 per cent of independent schools receiving 80–95 per cent of the public funding for similar government schools, the state and federal governments are close to funding the entire cost of the teaching workforce in non-government schools in Australia. Parental “capacity to pay” has become an irrelevance.

The bloke on the Brisbane bikeway can no longer be justified in the belief that the non-government sector provides a substantial saving for the taxpayer. That is not a criticism of Catholic and independent schools, which can be defended on other grounds, though cost-effectiveness for governments is not one of them.

The great political divide

Finally, the bloke on the bikeway is right in believing that the two sides of politics are poles part. But the government and the opposition are fluffing around the margins of the issue, and neither appears to understand the magnitude of the reform that is needed, or – if they do – to have the capacity to tackle it.

Equity and school outcomes have both deteriorated sharply since we wrote the Gonski report. Some stark realities now shape the context in which governments – state and federal – must make decisions two months from now about how Australian education might recover from its long-term continuing decline.

The present quasi-market system of schooling, the contours of which were shaped by the Hawke and Howard governments, has comprehensively failed. We are on a path to nowhere. The issue is profoundly deeper than argument about the last two years of Gonski funding, or changes to the governance of federal–state funding arrangements. If governments are to provide genuinely needs-based funding, the individual school must be the common unit for measuring need.

Neither side of politics has come to grips with what needs-based funding really means. No good will be achieved by allocating Commonwealth funding to states on some sort of equalising basis, as Senator Birmingham seems to envisage, unless each state allocation is the sum of the measured needs of each individual school within the state.

Nor would anything of lasting substance be achieved by severely reducing or removing the funding to the wealthiest non-government schools with an ICSEA value above 1150, which take fewer than 200,000 students or less than 5 per cent of the school population: it would be a handsome saving of $900 million per annum but still not get to the root cause of the problem.

The current arrangement for block funding of Catholic and government school systems, based on an average measure of their socioeconomic status rather than the aggregated socio-educational disadvantage of each individual Catholic and government school, must be replaced.

As several states have already shown, it is entirely achievable to use the individual school as the base unit for measurement: the elements of aggregated social disadvantage – low socioeconomic status, Indigeneity, English language proficiency, school size and remoteness – can readily be calculated from existing data for government schools and for Catholic systemic schools, and can be assembled from school data for independent schools.

New architecture is needed to bring state and Commonwealth funding together on the basis of the individual school. The current complexity of government, Catholic and independent sectors, each receiving recurrent and capital funding from two government jurisdictions but in different proportions from each level of government, and with two of the sectors charging fees, all within a framework of seven governments at different stages of three-year electoral cycles, is unworkable.

Further, the view that government schools are a state matter, and that fee-paying, government-funded non-government schools are a Commonwealth matter is outrageous: the federal government has a role in relation to the education of all young people in Australia, and every state minister for education has responsibilities for the education of all young people in the state, regardless of the schooling sector they attend.

The funding architecture should be greatly simplified by making the individual school the basis for funding. Each would receive a core component according to enrolment, and a supplementary component based on agreed national loadings for the elements of aggregated social disadvantage. The core component for fee-paying schools should continue to be adjusted according to parental capacity to pay, but on a much more realistic basis than at present. The allocations to the government and Catholic systems should be sum of the grants to the schools in those sectors; the individual independent schools should continue to be funded directly.

The cost of external systemic support, such as regional or diocesan consultancy and administration for government and Catholic schools, should be deducted from their total allocations determined as the sum of the needs of their schools, within guidelines agreed by governments, and should be public. The Association of Independent Schools, which provides similar support for independent schools, should be funded by the schools that choose to join it, on a user-pays basis.

The My School website should show the total grant for each school, the amount deducted by the system for consultancy and administration, and the external services being provided to the school on the basis of that deduction. That would be a significant step towards greater autonomy for schools, and a long overdue level of transparency. A workable alternative would be for the state governments and the Catholic Church to pick up the full costs of their bureaucracies from their own resources.

Federal and state funds would need to be pooled. Both state and federal governments have a responsibility to determine priorities for expenditure on education; the pooling of funds would mean that those priorities would need to be determined jointly by the ministerial council, and for fixed and longer periods, bringing greater stability and certainty for schools and system planning, and reducing the impact of seven staggered three-year electoral cycles on school planning, which necessarily has much longer horizons.

Increasing urgency

We are in the absurd situation where we virtually have two publicly funded systems. One system is government-funded, can’t charge fees, is inclusive in that it has a legal responsibility to enrol all students who wish to attend, and has a range of obligations and accountabilities to government. The other is government-funded to almost the same extent, sets and charges fees in addition to its government funding, is exclusive in that it has a selective enrolment process and can legally refuse admission, and has a statutory exemption from a range of anti-discrimination provisions.

The charging of fees on top of being largely government-funded distorts enrolments between schools and sectors, which is the key factor causing our steepening socio-educational gradient. Given their level of fees, most of these schools don’t require government funding to provide a quality education. The high level of government funding is quite out of proportion to parental capacity to pay.

As non-government schools and systems are able to borrow money, the excess recurrent funding can be used to underwrite the servicing of loans on capital works. Unnecessary government funding is therefore fuelling competition between over-funded non-government schools on the one hand, and between government and non-government schools on the other. This situation is now common in suburbs and towns across Australia, where adjacent schools can receive similar levels of taxpayer support yet operate under quite different obligations to the taxpayer, in facilities of sharply differing standards, and with clientele deeply divided on the basis of class, ethnicity and income.

This is not where we want to be.

So, the Gonski report: vision or hallucination?

School funding is not a matter of optics, either real or imagined. The Gonski report was neither a prophetic revelation nor a deceiving illusion: it was a proposal for governments to make a coldly rational investment decision in order to achieve a specific return – the full realisation of our national stock of human capital – and this requires sweeping away the existing funding structure and replacing it with something entirely different and better.

Five years later, that has become a critically urgent imperative. •