China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism

By Rana Mitter | Belknap Press | $47.95 | 336 pages

“There never was a good war,” wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1783, and few privy to the devastation of China during the second world war would have disagreed. Rana Mitter presented us with an account of that war in his 2013 book, Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937–1945. Now, in China’s Good War, he returns to the subject, this time with an eye to how it is being curated as a historical topic in the People’s Republic of China. The “good war” of the title proves not to be a rebuttal of Franklin but a reference to Studs Terkel’s “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II, winner of the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction.

Mitter is fundamentally interested in the Chinese government’s efforts to integrate the history of China’s war with Japan into the world history of the second world war. As he indicates, success in these efforts would mean a China-centred history in which China replaced the Pacific as the significant theatre in the east and the Chinese rivalled the Americans in importance in combatting the Japanese.

The book is overtly aimed at showing (to quote the subtitle) “how World War II is shaping a new nationalism,” though the nationalist character of China’s project is mainly left implicit. Statist aims seem more obvious. In chapters on formal historical scholarship, TV drama, film and other forms of popular history, sites of historical memory, and historical debates, Mitter shows that remembering the war, and reminding the rest of the world about it, is helping China to burnish its “claim to ownership” of the post-1945 world, “deny Japan any significant role in the region” and “add moral weight to China’s presence in the region and the world.”

China had a long war with Japan: just over eight years counting from the attack on Beijing in July 1937 to the Japanese surrender in September 1945. These days, as Mitter tells us, children in China are taught about a fourteen-year war that begins with the Manchurian crisis of 1931 and the Japanese occupation of northeast China. The September 18th Historical Museum in Shenyang, built to commemorate this starting point, was formally opened in 1999, but Mitter dates the new orthodoxy to a 2015 statement by Xi Jinping. In 2017, the education ministry decreed that the iconic “eight-year war” was henceforth to be called the “fourteen-year war” in all textbooks. Historians in China have greeted this new development with a mixture of irritation and resignation.

Early sign: the September 18th Historical Museum in Shenyang. Antonia Finnane

Mitter’s own view is that China did not regard itself as being at war with Japan during the six years before 1937 (which were admittedly marked by extreme tensions and even outbreaks of armed conflict between China and Japan). His introductory chapter provides an outline history of the war, and it is for the most part the eight-year war. As he goes on to show, research and publishing on war history in recent years have also mainly been concerned with events that took place in those years.

Prior to the 1980s, Chinese research on the war years was largely directed at party history rather than war history. The result, not surprisingly, was a body of work that contrasted a positive interpretation of the Communists with a “very hostile analysis of the record of the Nationalists.” (Even Western historians held a negative view of the wartime Nationalist government.) When China entered a period of relative openness in 1980, discussion about the war widened. In this newly established field of research, moves were made to rehabilitate the Nationalists’ role in the war. As it turned out, they had done most of the fighting.

The treatment of the Nanjing Massacre of 1937 epitomises historiographical change in the 1980s. A much-studied topic in Japanese and English as well as Chinese-language works, the massacre doesn’t dominate Mitter’s book but he frequently returns to it. Research on the massacre carried out at Nanjing University in the 1960s had been suppressed during the Mao years but was finally allowed to see the light of day in the eighties. A museum commemorating the massacre was built in 1985 and redeveloped in stages in subsequent decades. Partly inspired by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, it is a standing reminder of Japanese wartime atrocities in China. Later, in the early 2000s, a number of documentary and feature films about the massacre were released, some to international acclaim.

In a historical landscape dominated by Beijing, attention to the massacre signified a new acknowledgement of local history, significant not least because Nanjing had been the Nationalist capital and also the capital of a collaborationist regime during the war. A comparable process of recovering local history has been undertaken for the wartime capital of Chongqing, another topic explored by Mitter.

The recovery of these local histories has been accompanied by a fever of interest in the Republican era, causing some concerns in Beijing. An effort to “own” the histories is the obvious strategic response. On 13 December 2014 (although Mitter doesn’t mention this) Xi Jinping presided over a ceremony at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum on the occasion of the first National Day of Mourning. The nation came to a standstill as air sirens sounded. In retrospect (since 2014 is a fairly random year in commemorative terms), that event seems to have laid the groundwork for the great victory parade of 2015, which marked the seventieth anniversary of the Japanese surrender.

Mitter was in Beijing for that parade — an event designed, he writes, “both for domestic political purposes and also to send signals to the outside world about China’s international role.” He uses it to highlight the significance of the second world war in the Chinese government’s repackaging of itself in a changing world order. If the war was remembered primarily as an anti-Japanese war in the 1980s, by 2018 it had become “the main Eastern battlefield for the global war against fascism.” In other words — in history, as at the present time — China was to be perceived as a world player, not merely a regional one.

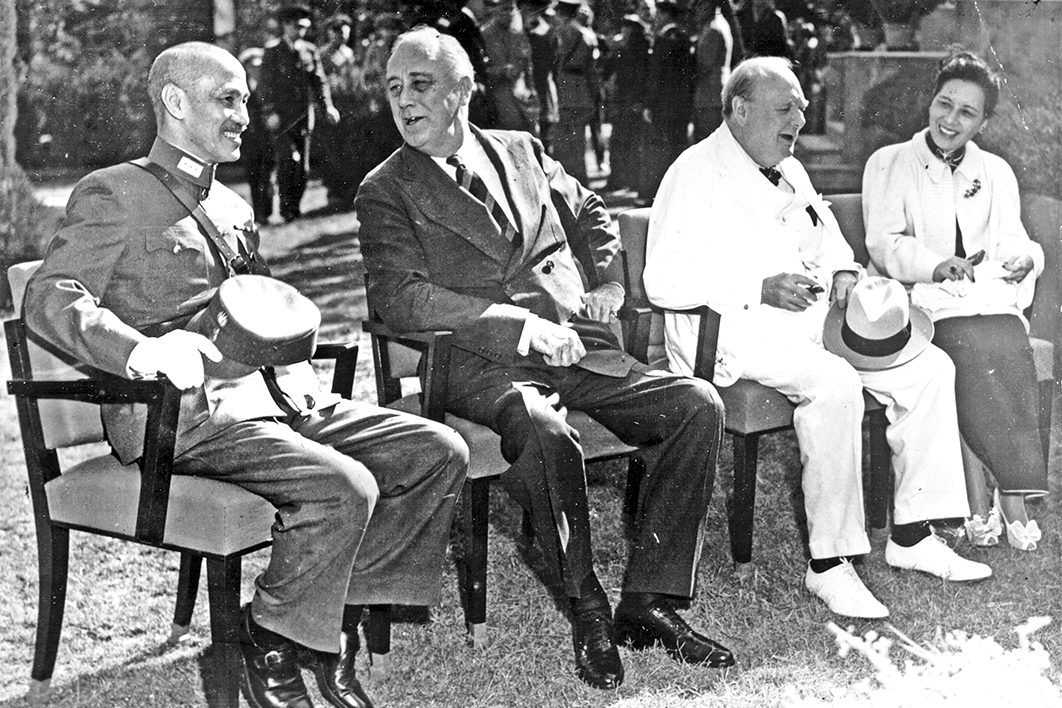

An important point of reference in the new war history is the 1943 Cairo Conference, at which president Chiang Kai-shek joined Churchill and Roosevelt to discuss postwar arrangements in Asia. In an absorbing discussion of the conference, Mitter shows that the point of the Chinese Communist Party’s present-day (re)writing of war history is to show not only that China fought the “good war” too. Even more importantly, it also participated in postwar planning. In other words, China was “present at the re-creation” of the postwar world.

The pace of change in Chinese historiography has been rapid, and the politics of the changes rather transparent. Mitter is far from the only observer interested in the relationship between the two. As a call for a greater awareness of history as ideology in China, his book is part of a growing chorus: Zheng Wang’s Never Forget Humiliation (2012), Huaiyin Li’s Reinventing Modern China (2013) and Bill Hayton’s The Invention of China (2020) all riff on similar themes. In similar vein, James Millward, historian of Xinjiang, has called on historians of modern China to be less lazily compliant with the revised standard version that passes muster as history in China.

All of this prompts consideration of what, if anything, students in Australia are learning about Chinese history. Sure enough, guidelines for the Chinese Revolution unit for the Year 12 Victorian Certificate of Education reveal a series of sub-topics that might well be taught from a critical perspective but nonetheless follow a path that could have been laid by the Chinese education ministry.

If teachers are asked any time soon to bone up on the 1943 Cairo Declaration, they could do worse than read Mitter on the subject. He writes a plain, uncluttered history that informs and explains in equal parts. In China’s Good War, he shows that the history of wartime China has been largely shaped by just one of its outcomes: the ascendancy of the Chinese Communist Party and the creation of a state that depends heavily on a certain sort of history for its legitimacy. •