Peter Parker begins the first of a projected three volumes on gay life in London, this one from 1945 to 1959, by quoting the novelist E.M. Forster. “What the public really loathes in homosexuality,” he came to write, “is not the thing itself but having to think about it.”

Two stories from the prewar period capture this precisely. One concerns Winston Churchill, who was talking about it once with a close friend. “I tried it once, you know,” the great man said. Did you… who with, he was asked. Ivor Novello the songwriter came the reply. What was it like? “Musical!” smirked Churchill, using a common term for homosexuality at the time. And then there was the man who told his son that he’d been called up for jury duty and had to attend a trial for sodomy. What happened? asked the son. “He got off, of course… Half of us didn’t think it was possible, and the other half didn’t think it mattered.”

Few people got off (always excepting the vulgar sense) in immediate postwar London. There was a feeling that morals had become too relaxed during the war, with female prostitutes also a cause for concern. A moral panic was evident in some local associations being formed to uphold public standards of behaviour. And convictions had risen: in 1947, 637 cases involving homosexual offences came up before the London magistrates’ courts, three times the number in 1942.

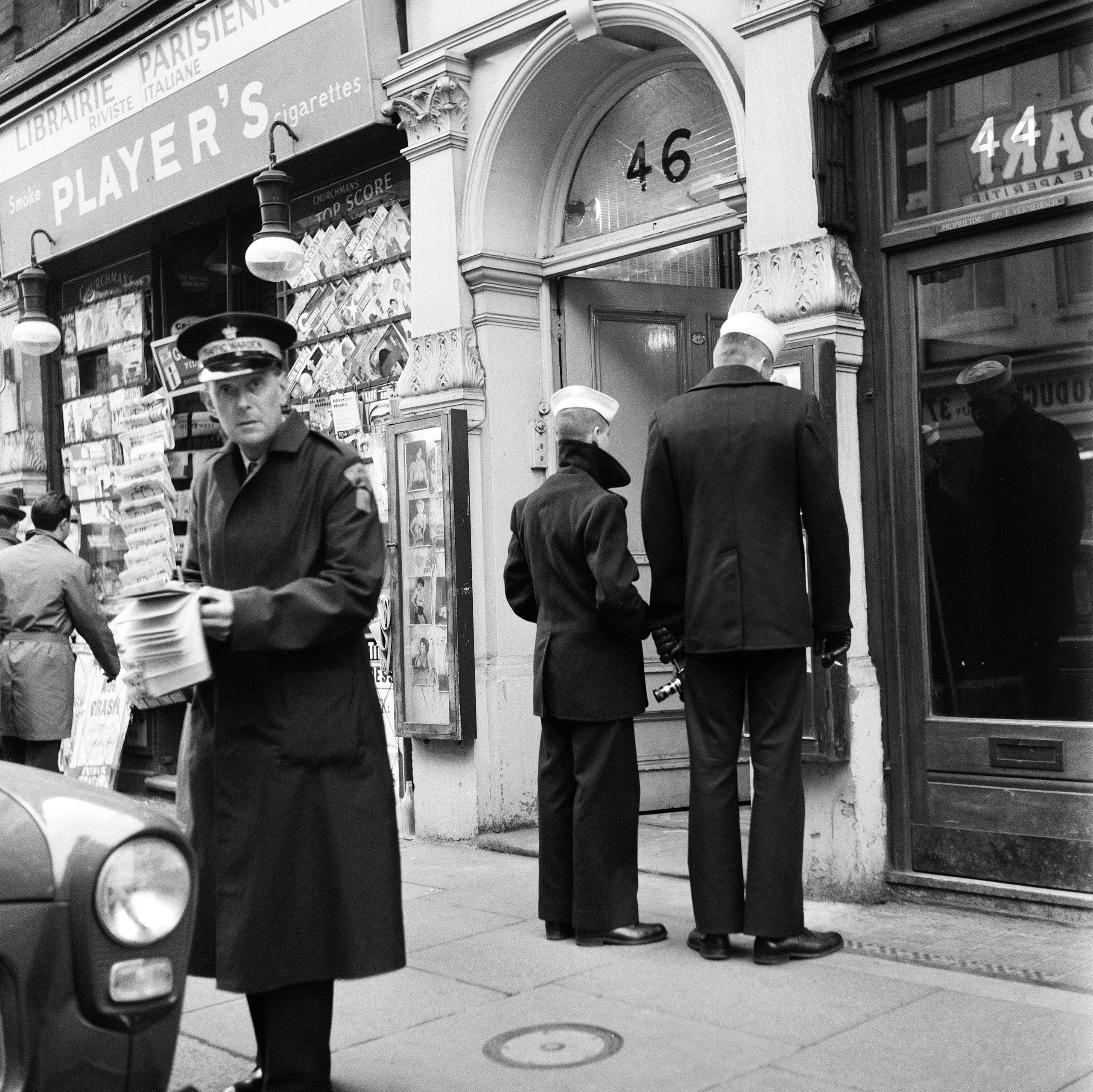

The excessive zeal of the police may have had something to do with it. In London, although not in the provinces, a gay couple living together were more or less left alone. But any interest a stationary man might appear to be taking in another, catching his eye, might land him in court. No distinction was made between a man seeking company, and a male prostitute on the beat. A second offence usually brought a jail term, and further offending could bring imprisonment for two years. (Offending with a minor or indecent assault understandably compounded the term.)

Certain places in the West End (like Piccadilly Circus tube), or particular public conveniences, were haunted by young policemen acting as decoys. Police promotion was often related to the number of convictions they procured. Scoreboards in police stations were not unknown. In this spirit Brian Epstein (of Beatles fame), once caught, found himself subject to a ghastly inflation: instead of just the decoy, by the time he reached the police station the number of men he had supposedly importuned had gone up to four. Later in court it rose to seven.

Meanwhile the time-honoured nexus of young guardsmen frequenting certain pubs to sell sexual favours continued — even as the well-known writer J.B. Priestley railed against poofs in the theatre. So, implicitly, did the Lord Chamberlain, who until 1967 acted as chief censor: plays with a homosexual theme, or characters, were not permitted on the public stage. Even a couplet by John Osborne,

I could try inversion

But I’d yawn with aversion

was cut from the text of Look Back in Anger.

The law, as it stood, functioned as a blackmailer’s charter — a former attorney-general stated that he would put at 95 per cent the proportion of known blackmail cases connected with homosexual offences. People would commit suicide rather than face exposure. One man threw himself in front of a train, two hours before he was to appear in court. Others were beaten up, robbed. A consequence, perhaps, of the upper English penchant for the common man, not the least disquieting aspect of the matter to those who saw such mixing as socially corrosive.

There was an extraordinary view, held dear not least in Labour circles, that homosexuality was almost unknown among working people. It was confined to upper-class decadents — who then corrupted members of the lower classes. “Perversion is very largely a practice of the too idle and the too rich,” thundered the Sunday Express. “It does not flourish in lands where men work hard and brows sweat with honest labour.” But as Parker points out, a table published in the mid-1950s showed that of 321 men brought to court for homosexual offences, schoolmasters, clergymen and men of independent means were vastly outnumbered by truck drivers, factory hands, clerks, unskilled labourers and other ordinary workers.

The defection to Russia in 1951 of Burgess and Maclean (Cambridge-educated Communist spies, one of them certainly gay) didn’t help. Shortly after the British press picked up that the US State Department — at the height of McCarthyism — was purging staff thought to be potential spies or security risks. The list included 325 homosexuals.

It was also feared that homosexuality was a manifestation of national decline, a fear by no means restricted to the tabloids, which warned “It grew in classical Greece to the point where that civilisation was destroyed.” One unsuccessful Tory candidate expressed the view that homosexuals should be hanged.

By the 1950s, nevertheless, there were signs of a shift. When the actor John Gielgud was brought before the courts on a homosexual offence, he was convicted. But not in the court of public opinion: at his next on-stage appearance he was wildly applauded. As E.M. Forster wrote at the time, “If homosexuality between men ceased to be per se criminal — it is not criminal between women — and if homosexual crimes were equated with heterosexual crimes and punished with equal but not with additional severity, much confusion and misery would be averted.” A sensational pair of trials occurred a few years later, involving a peer and the articulate journalist Peter Wildeblood; it was plain that the police had acted corruptly. Wildeblood’s persuasive book Against the Law, written after he had served a prison sentence, was a further impetus towards change.

Some time before, a manual (reprinted) had advised homosexuals on how to pass for straight. But now books also began to appear discussing homosexuality not as a criminal problem but as a psychological one. Some sociologists based their work on interviews with gay men (often indifferent to the fact that there might be distortion since most of those were felons.) But even here the prevalent view was that some form of treatment would solve the problem, and preferably eliminate homosexuality altogether. The way was opened to a blitz of ECT treatment.

In 1954 a committee was set up by the Conservative government to examine the laws relating to homosexuality and prostitution. (Something has to be done about it…) It was headed by Sir John Wolfenden, who had a gay son. (He asked the lad to steer clear of him while the committee was deliberating, adding that he should be sparing with his make-up.) But then the committee had been suggested by a bisexual.

Opinion was divided. On one hand, the Church of England’s Moral Welfare Council had published a pro-reform pamphlet; on the other, the magistrates’ association voted decisively against any change. When the report was tabled three years later, Wolfenden was careful to state in a TV interview that it was not condoning homosexuality in any moral sense.

It is not surprising, then, that a Conservative government would be dilatory in the matter. Wolfenden was not debated in the Commons until 1960. But the whole conspectus of attitudes had been evident in an earlier debate in the Lords. “We must not laugh at India,” said Lord Brabazon, “with their untouchables; we have our untouchables here in these poor people who are inverts.” The Bishop of Rochester — professional dispenser of Christian charity — likened homosexuality to leprosy. Demonisation continued in the tabloids: “How to Spot a Possible Homo,” ran one article. It was reprinted here in Australia, with the tentative “possible” dropped. Entrapment and convictions continued.

Eventually a reforming act was passed in 1967 — but with restrictions. It would apply to consenting adults in private only in England and Wales (not Scotland or Northern Ireland); nor to members of the armed services or the merchant navy (the fear of decline and fall).

Peter Parker, an accomplished biographer and man of letters, has produced an impeccably edited volume. For his documentary history he has drawn on a wide variety of sources, sometimes juxtaposing high society diaries, records of convictions, hostile tabloid accounts, touching personal letters. (The diary entry giving a finely drawn account of the rent boy Johnny Walsh is a minor masterpiece.) Introductory notes are brief, succinct and complemented by short biographies.

Parker also uses extracts from an astonishing number of gay novels. He is determined to give us the flavour of the period, so he chooses a fictional portrayal of Quentin Crisp rather than a highly coloured extract from the autobiographical The Naked Civil Servant, written much later. (It was a good career move of Crisp’s to pick that name rather than the one he was born with, Dennis Pratt.)

This is not a history but an extraordinary source book — the grist to many mills. (Perhaps it’s a bit surprising that it’s been published as a Penguin Classic.) A high standard has been set for the following two volumes. But let’s hope they, at least, will be given an index. •

Some Men in London, Volume 1: Queer Life 1945–1959

Edited by Peter Parker | Penguin Classics | $65 | 458 pages