Just so we know what we’re talking about, let’s begin with an example.

Former National Party leader Barnaby Joyce recently made some comments about the makeup of the Voice to Parliament:

What you’ll see is people on $300,000 a year, twenty-four of them, and they won’t be elected, they’ll be selected. Which one are you going to select? Which tribe are you selecting from? I’ll give you a little tip, they don’t get along. You pick one, watch out, the other one’s coming. Right down to families, families don’t get along. A group of people, highly paid, they’ll be like a quasi House of Lords.

As the late, great Tommy Cooper used to say, “Deja Moo: the feeling that you’ve heard this bullshit before.”

We all recognise bullshit when we see it, but do we recognise it as a genuine philosophical concept? Could we one day find ourselves attending an erudite lecture on the topic by Oxford University’s Rupert Keith Murdoch Professor of Philosophy?

If you were in the habit of visiting bookshops around 2005 you may recall encountering a little hardback called On Bullshit. Written by someone with the unlikely name of Harry G. Frankfurt, it became an unlikely bestseller.

On Bullshit looked like one of those “joke” books they stack next to the cashier’s desk. I’d happily bet that many of its buyers were jaded Christmas shoppers on the lookout for a last-minute stocking stuffer. But it was, in fact, a serious work of scholarship, with a serious message.

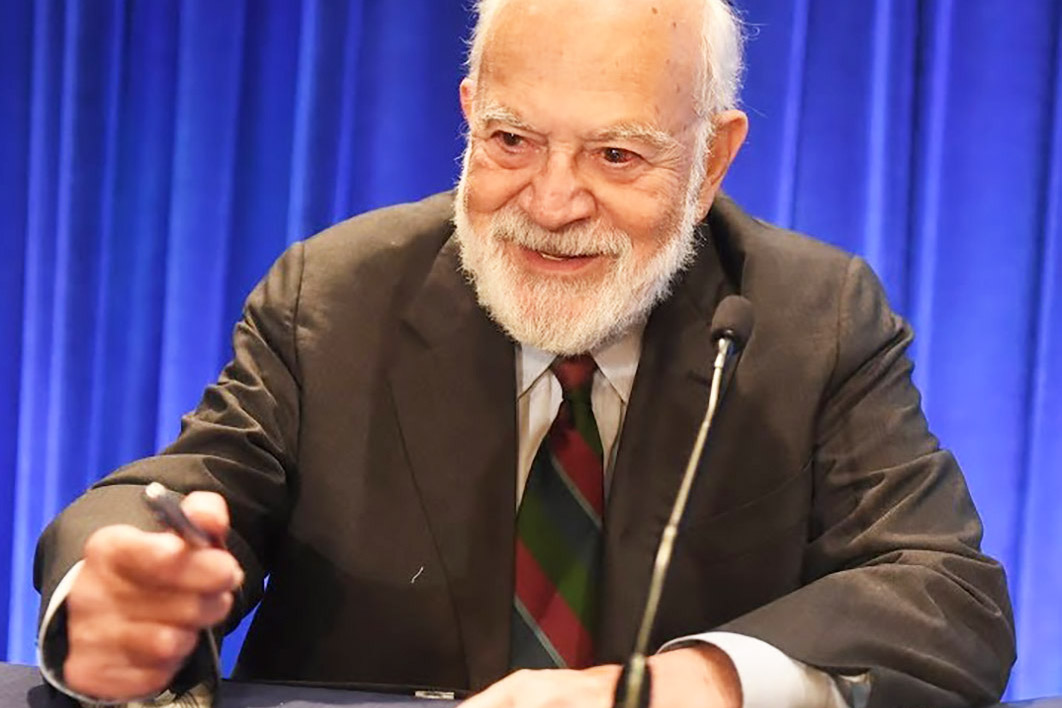

Frankfurt, who died this month at the age of ninety-four, was a professor of philosophy at Princeton University who made substantial contributions to moral philosophy. He is also the father of Bullshit Studies and On Bullshit is the nascent discipline’s seminal work.

I’m sure he hoped to be remembered for his writings about free will and moral responsibility in a deterministic universe, but it was his pathbreaking theorising on bullshit that got him invited onto 60 Minutes and Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show, and assured him a place in the popular culture.

By all accounts Frankfurt was a committed intellectual: it was philosophy, not fame or money, that got him out of bed each morning. Predictably, he was also committed to the truth — as a concept and as a practice. Asked why he chose Descartes as the subject of his first book, for example, Frankfurt happily admitted that he was attracted to the brevity of the Frenchman’s books.

First published in 1986 as an essay in Raritan and then as that very short book, On Bullshit grabbed the imagination of so many because it identified something that was obvious as soon as Frankfurt pointed it out: “One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.”

Using his training as an analytical philosopher, Frankfurt then went further and defined this phenomenon: bullshit is not just lying, it is indifference to the facts: “the essence of bullshit is not that it is false but that it is phony.”

Truth-tellers and liars, Frankfurt argues, are playing in the same game on the same playing field. Liars may seek advantage by lying to hide the truth but, just like an adherent of the truth, they know what it is. In essence, they agree about the rules of the game and have their own kind of respect for the facts. A liar understands that if he’s caught out in a lie, there will be consequences.

The bullshitter, on the other hand, is sitting in the grandstand, tweeting on a smartphone, and pretty much ignoring the game of truth and lies. The bullshitter’s intentions are very different. As the old saying goes: “Never tell a lie when you can bullshit your way through.”

As Frankfurt writes:

When an honest man speaks, he says only what he believes to be true; and for the liar, it is correspondingly indispensable that he considers his statements to be false. For the bullshitter, however, all bets are off… He does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of truth than lies are.

The great bullshitters of our age — you know who I mean — are certainly highly skilled purveyors in counterfeit thought; they don’t care if what they say is true or is not true.

What they really care about is conveying a politically useful impression of themselves to their audience; they care about their image and the power that flows from it. They bluff to deceive and deceive to bluff; they cherrypick ideas and facts and present them as an advertisement for themselves.

This is why Frankfurt believed that bullshit is a greater dishonesty than lying: if you don’t have to believe that something is true, you’re free to believe that anything might be. In a democratic system where accountability is supposed to depend on facts, this is highly corrosive. The public square becomes a kickboxing ring without an umpire.

Unfortunately for Bullshit Studies, Frankfurt’s argument is weakest when he attempts to explain just why there is so much bullshit around nowadays. “Bullshit is unavoidable,” he argues, “whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about.” Now this is true — to a certain extent.

Writing near the beginning of the digital age, Frankfurt never anticipated that the rivers of bullshit would soon become tsunamis, supercharged by the internet, social media and a 24/7 media cycle.

But none of this really explains where the original impetus comes from and why it’s so rewarding for its proponents. Unfortunately, I think it comes from us: the audience.

Barnaby Joyce says things, and because they’re colourful and he’s a member of parliament, the media reports them. Then, as he intends, someone else responds in outrage and the media reports on that. By creating a clickfest, Joyce has manoeuvred debate about the Voice referendum to just where he wants it: circling the drain.

Frankfurt’s short essay — great as it is — would have benefited from being just a bit less short: bullshit has a long history.

In his classic essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” first published in Harper’s Magazine in 1964, the historian Richard Hofstadter explains that American politics has always been “an arena for angry minds.” A nation’s political rhetoric, he says, reveals its political psychology — and it’s not a pretty picture.

“I call it the paranoid style,” writes Hofstadter, “simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness and conspiratorial fantasy.” Take one bullshitter, add a dash of social media, stir into a bowl of paranoid style and you get a recipe for disaster.

Hofstadter’s essay is full of examples from American history, such as the red scare of senator Joe McCarthy, but he argues that the paranoid style can be found anywhere.

It’s a view supported by recent science, As one survey of the field suggests, “paranoia should not solely be viewed as a pathological symptom of a mental disorder but also as a part of a normally functioning human psychology.” Being a bit paranoid was an evolutionary advantage. Our ancestors who were too scared to go into the dark forest may have been more likely to pass on their genes because oftentimes the dark woods were dangerous. And then the tribe’s big man — possibly the original bullshit artist — came along and exploited it.

Harry Frankfurt learnt the hard way about the dark side of our fascination with bullshit. Impressed by the popularity of his little book, Knopf paid him a six-figure advance for whatever he came up with next. The sales of the book he produced, On Truth, were disappointing. •