Mist billows up the cliff face, merging with the low cloud and shrouding the valley in a thick white blanket. This is often the view from Point Lookout, a high spur of the New England tableland, northeast of Armidale, near the headwaters of the Styx and Serpentine rivers. On a clear day, the view stretches over the high country in the west and eastwards out to sea, and sharp rays of light pierce the canopy of the rainforest below, setting the wet understorey of moss and ferns and staghorns aglow. Today, as the clouds heave across the granite escarpment, the snowgums become lost in the white.

I am here on the trail of the archaeologist Isabel McBryde, who roamed the landscape of northern New South Wales in the 1960s in search of rock art and ceremonial grounds, scarred trees and surface scatters, middens and massacre sites, rock shelters and quarries. “We aim at a complete, systematic and objective record of all archaeological features in an area,” McBryde wrote of her survey team in 1962, “not only the most spectacular.” Her study area extended from the high plateau country of the tablelands, which slopes gently to the black soil plains of the Darling Basin, to the broad rivers of the subtropical coastal valleys in northern New South Wales. Sites on the escarpment, such as Point Lookout, marked the divide between these dramatically different environmental zones. Through her survey, she sought to discern the cultural implications of these varying climates and environments: she yearned to understand the personality of New England.

But as I make my way through the undergrowth on this cool, damp May morning, I am haunted by the words of the great Australian poet Judith Wright, who came here often as a child. She lived on the tablelands and camped at Point Lookout with her father, as he had with his mother. She remembered being mesmerised by the splendour of the cliffs, the mystery of the thickly forested valley and the “the great blue sweep of the view from the Point to the sea.” But she saw a darkness here, too. To the north of Point Lookout, jutting out from the plateau and dropping in sheer cliffs into the thick rainforest below, is a place once known as Darkie Point. Wright’s father told her the story of how it got its name: how, “long ago,” a group of Aboriginal people were driven over those cliffs by white settlers as reprisal for spearing cattle. Their sickening plunge was inscribed with Gothic flair in one of Wright’s early poems, “Nigger’s Leap, New England” (1945). The story was later revealed to be an “abstracted and ahistoricised” account of a documented event.

Through her poetry, and especially in her later histories, Wright sought to confront the violence in Australian settler history and to reimagine it through the eyes of the first Australians. Her words breathed sorrow and compassion into the early encounters between settlers and Indigenous people, evoking the tragedy of the Australian frontier. Her love of the New England highlands was bound to a creeping uneasiness about its past. She lived in “haunted country.” In another early poem, “Bora Ring” (1946), she mourned the passing of a dynamic world:

The hunter is gone; the spear

is splintered underground; the painted bodies

a dream the world breathed sleeping and forgot.

The nomad feet are still.

In seeking out such stories, Wright was fighting against what anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner described in 1938 as “a mass of solid indifference” in Australian culture to Indigenous Australia. In his 1968 ABC Boyer Lectures, Stanner coined the phrase “the great Australian silence” to describe the phenomenon, which could not be explained by mere “absent-mindedness”:

It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned into habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness on a national scale.

The silence to which he referred was largely a phenomenon of the twentieth century, rather than colonial Australia. And its mist was clearing by the time he spoke those words. Despite a tempestuous and harrowing history, Aboriginal people had survived the invasion, and they were making their voices heard. The fog was lifting from Darkie Point.

When Isabel McBryde came to New England in 1960, she expected to encounter the haunted landscape of Wright’s early poems: a land stripped from its first inhabitants, their culture and tradition “splintered underground.” She had been led to believe that her study would be a “matter of archaeology and the distant past.” But as she searched for traces of Aboriginal culture in the landscape of New England, her views began to change. She found a series of stone arrangements to the southwest of Point Lookout, near the Serpentine River, and recorded the cairns, walls and standing stones that protruded from the steadily encroaching bush. Across the tablelands she found carved trees and surface scatters; she mapped axe quarries on the ridgelines and excavated campsites under towering granite boulders; she recorded ancient middens on the coastal plains and wandered through old bora grounds in the river valleys. She formed relationships with locals, absorbing their intimate knowledge of the history and traditions of the country, and worked with landholders, teachers, historians, field naturalists and Indigenous people.

“The great blue sweep”: the view from Point Lookout towards what used to be called Darkie Point. Billy Griffiths

And as she surveyed this vast region, and imbibed the lore of the land, she stopped thinking of the Aboriginal past as “a dream the world breathed sleeping and forgot” and started seeing it as a living heritage, maintained through powerful connections to country, “preserved faithfully by a small community” and “now the focus of a revival of interest in traditional culture and values.”

This quiet revelation, experienced by many researchers throughout the 1960s, would forever alter the course of Australian Aboriginal archaeology. As McBryde reflected in 2004, “It gave a whole new dimension [to the field] and also made new demands” — no longer were academic priorities the only priorities. Archaeologists were compelled to be cultural scholars as well as researchers, and they were faced with a conflict of obligations: “your obligation to investigate and record and your obligation to respect the wishes of the members of the creating culture.” The story of Australian archaeology — and Isabel McBryde’s career — is inextricably entwined with that seismic shift in Australian historical consciousness.

Isabel McBryde is an enigmatic character in Australian archaeology. She is at once conservative and radical, gentle and passionate, modest and visionary. She has quietly, patiently transformed the way we relate to the Aboriginal history of Australia. One of her students, Sharon Sullivan, described her as “a real lady”: “kind,” “courteous” and “thorough,” with a “powerful intellect” and a “steel-edged, or should I say stone-edged view, of what is ‘proper.’” Her conservative demeanour belied her innovative and often subversive ideas and practices, and the significance of her early contributions to Australian archaeology remains understated. If John Mulvaney is the so-called father of Australian archaeology (a term with which he was uncomfortable), then McBryde is undoubtedly its mother.

McBryde had no direct contact with Aboriginal people as a child. She grew up in a seafaring family and moved constantly, living in Fremantle, Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne before the age of nine. She was used to her father, a merchant seaman from Scotland, being away at sea, and she took great comfort in his steady stream of letters. She and her older sister were cared for by their mother, who had worked as a secretary before her marriage. Occasionally her mother talked of the Aboriginal people she had known when she lived in Kalgoorlie, but, for the most part, the not-too-distant past was obscured. “Why,” McBryde reflected in her seventies, “didn’t I pick up that dissonance in the reporting of Australian history?” Her experience of growing up in white, middle-class Australia in the 1930s and 40s speaks to the heart of “the great Australian silence” that Stanner described in 1968. Even the most socially aware Australians were subject to the structures that marginalised Indigenous Australians.

McBryde recalled a childhood of writing and reading poetry, practising the violin and “devouring” books on the train as she commuted to school. She developed a fascination with the classical world at an early age, especially ancient Rome, and when she matriculated in 1952, she enrolled in Latin and history at Melbourne University. Like Mulvaney, she envisaged a career in school teaching and, also like Mulvaney, her first glimpse of another career path came under the tutelage of the historian John O’Brien. In his lectures on the classical world, delivered in a precise, even style, he urged his students to query accepted wisdom — to return to the primary sources and develop their own interpretations of the past. It was an empowering approach and it encouraged an inquisitive eye and a broad understanding of the range of historical evidence available. McBryde wrote her honours thesis on the Roman poet Lucan, who raised questions of liberty and power in his epic on civil war before falling foul of his friend, the mad emperor Nero; she pursued similar themes in her master’s thesis on expressions of resistance to the Roman government at the end of the first century. Spurred on by her passion for the ancient world and the encouragement of her teachers, McBryde decided to pursue a career in the academy.

When she graduated in 1957, the possibility of a career in archaeology seemed no more than a dream. As curator Frederick McCarthy put it drily in 1959, archaeology remained “a non-career course” in Australia: there were no jobs in the universities, no funds to finance excavations and no institutional support for the lone researcher. But McBryde had heard of Mulvaney’s work at Fromm’s Landing in South Australia, and as enamoured as she was of the classical world, she could see the importance of his pursuit of Australia’s ancient past. Australian archaeology, she decided, would be “more worthwhile and realistic than classical archaeology.” But the only way to study prehistoric archaeology was to travel abroad, and all the scholarships of the day were designated for “young men.” She would have to pay her own way. She lectured in ancient history at the University of New England for six months in 1958 and then, with the support of her parents, sailed to the United Kingdom.

Cambridge University seemed an obvious choice. It had a strong archaeology department under the guidance of Grahame Clark, and postgraduates had the privilege of small classes, fieldwork opportunities and ready access to leading intellectuals. Clark’s interest in world prehistory made Cambridge especially attractive. His desire to fill in the gaps of global knowledge — to gain an outline of the diverse “cultural endowment of mankind” — led him to encourage and facilitate research abroad and to equip his students with the expertise necessary to pioneer a new field. In his office he had a map of the world covered in colourful pins, a physical manifestation of his vision for Cambridge’s international role. Each pin represented an archaeologist from the Cambridge diaspora, from Louis Leakey’s groundbreaking excavations in Kenya and the Rift Valley to Jack Golson’s pioneering efforts in New Zealand. When McBryde arrived in 1958, a lone pin pierced the heart of Melbourne, representing John Mulvaney’s Australian contribution to the “Cambridge archaeological empire.”

The archaeology and anthropology department was located in a gloomy Edwardian building in Downing Street that also housed the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Lectures were held in an uncomfortable theatre alongside cabinets filled with antiquities from all parts of the world. But the department had a “compelling atmosphere” and McBryde found her time there to be “intellectually, very, very stimulating.” These were the heady postwar years and she recalls feeling an exciting sense of possibility about what could be achieved. Many of the major discoveries in European and British prehistory had been made in McBryde’s lifetime. As Golson reflected, “The discipline to which we had apprenticed ourselves was young and the opportunities it offered seemed limitless.” And the value of archaeology at Cambridge was undisputed. Clark described it as being “as necessary to civilised man as bread itself.”

The Cambridge model of archaeology was dominated by the methods and principles of Mortimer Wheeler, who emphasised the importance of systematic, stratified excavation, while other forms of archaeology were considered to be, in McBryde’s words, “the province of the non-digging amateur.” McBryde was initiated into this tradition during excavations at an Iron Age farmstead and two Roman forts on Hadrian’s Wall. But she was also drawn to another strain of archaeological thought. She found Clark’s ecological approach, which combined documentary and environmental evidence, “eminently translatable” to the Australian context. And she was intrigued by the work of O.G.S. Crawford and Cyril Fox, who viewed an entire landscape as an archaeological site: “The history of the part,” Crawford argued, “cannot be divorced entirely from the history of the whole.”

By studying a region, not simply a site, and by focusing on interactions between people and land, Crawford was able to read the English countryside in a new light, finding Roman roads and Celtic fields, barrows and quern quarries, megalithic monuments and medieval castle mounds. “The surface of England is a palimpsest,” he wrote in 1953, “a document that has been written on and erased over and over again; and it is the business of the field archaeologist to decipher it.” His method was to look for patterns in the landscape, to study maps and aerial photography, paying particular attention to topography, and then to walk the country, searching for the cultural in the natural. This was his primary source. Secondary sources, such as local histories or seeking out “the old-time local antiquary” were useful, but walking, he believed, was “preferable to talking.” Cyril Fox took a similar approach. He sought to understand the “personality of Britain”: how the nature of the landscape had affected “the distribution and fates of her inhabitants and her invaders.”

McBryde gained firsthand experience of these geographically oriented methods in the last few months of 1959, when she took a scholarship to work in the British School of Archaeology in Athens. There she studied sites across a whole landscape, asking why they were where they were and what connections they had with other sites, and exploring the relationships between history and landscape. It was a fusion of two of her longest-held passions, classics and geography. It was also her introduction to understanding the sacred and the mythic in landscape.

Isabel McBryde’s return to Australia in 1959, after a year abroad, doubled the number of professionally trained Australian archaeologists. She dived immediately into fieldwork, joining John Mulvaney in excavating rock shelters at Glen Aire, Cape Otway, in January 1960. By that stage, Mulvaney already had a vision of the key questions in Australian archaeology. The best way to approach them, he believed, was though careful, systematic excavation of deep stratified sites: “The cornerstone of prehistory is stratigraphy, and in this pioneering phase of Australian research, precedence must be given to the spade (or preferably the trowel).”

In her new role as lecturer in prehistory and ancient history at the University of New England, McBryde began to articulate a different vision. Echoing Crawford, she argued that regional field surveys, in combination with stratigraphic excavation, should form the backbone of any archaeological program. Her head of department, historian Mick Williams, shared her regional vision and had already established connections with local historical societies and field naturalists. McBryde was the first female lecturer in the Department of History, and she was alone among her colleagues in using material culture as a historical source. When introduced as an “archaeologist,” she was often asked by those outside the university: “What is there for you to do here?” She sensed the same question on the lips of her colleagues.

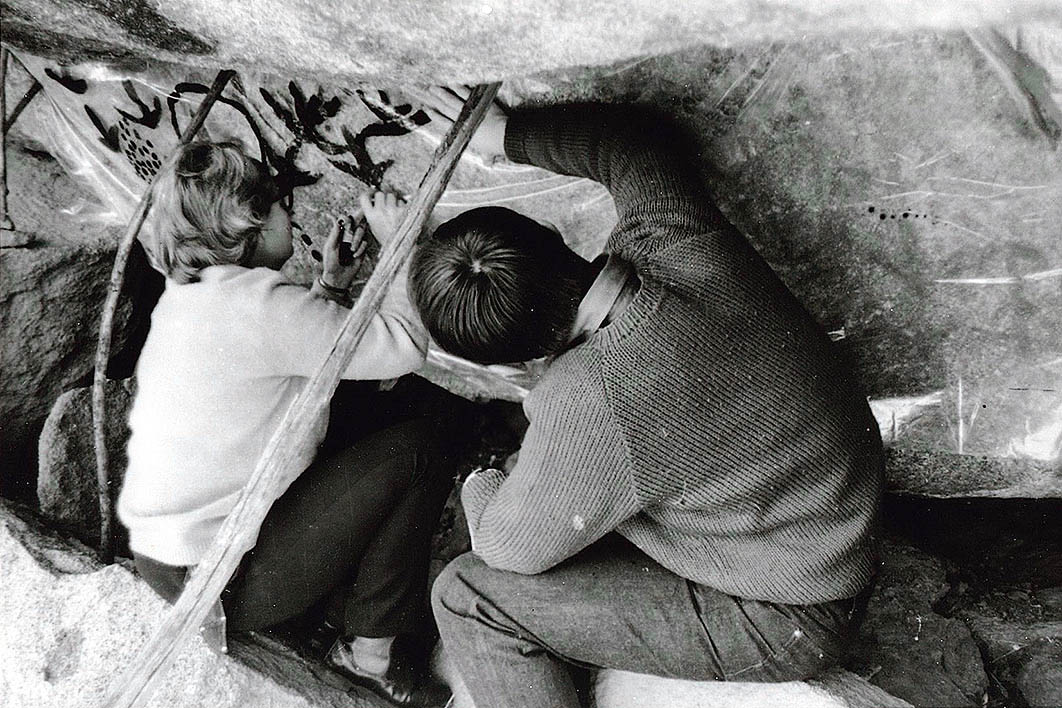

“Nerve and nous”: Isabel McBryde and University of New England students at Schnapper Point on the north coast of New South Wales. Courtesy of Isabel McBryde

Because of the lack of awareness of Indigenous history, she devoted much of her time to community outreach. She advertised the potential of the field, giving public talks at schools and regional societies across northern New South Wales and introducing concepts such as “antiquity” and “cultural change” to lay understandings of Aboriginal Australia. Through these talks, and in an early film on archaeological techniques, she joined Mulvaney’s attempts to rein in the persistent culture of surface collecting and educate the broader public on the importance of protecting Aboriginal sites: “Occupation sites in Australia (middens, rock shelters and open stations) are not so numerous that we can afford to be prodigal with them, to allow them to be destroyed… to be dug carelessly by treasure-hunters whose sole interest is the collection of curious relics for the family mantelpiece.”

These public meetings also allowed her to conduct valuable research. Unlike Crawford, McBryde prioritised talking alongside walking. She sought out and interviewed members of the local Aboriginal communities on the tablelands and the coastal plains, and fostered interest and involvement among locals with the belief that a conversation over a cup of tea could yield as much historical insight as a week in the field. In the Clarence Valley especially, McBryde formed connections with Bundjalung people who maintained a strong sense of cultural continuity despite the ravages of dispossession. Over time, her views on site protection became more inclusive: “If we argue for conservation of sites, for protective legislation, and acknowledge the very real concerns of the Aboriginal people, then we should also argue for Aboriginal involvement in decisions of site management, on conservation policy and on research.” If the deep past was a living heritage, then engaging with Indigenous communities, and making the insights of archaeology accessible to them, seemed to be fundamental to any research program:

Unless archaeology, in the present, addresses social questions, unless it is “peopled” archaeology, its representations will lack dimensions of meaning as pasts, as history. If it fails to interact with other groups within society, it is not accessible to their poetics, it denies to them aspects of their past.

The landscape of northern New South Wales lent itself to field survey. The thin soils of the tablelands meant that deep, layered sites were few and far between, while the coastal plains were dominated by recent shell middens: the cultural artefacts, in archaeologist Sandra Bowdler’s words, of “the unremitting efforts of woman the gatherer.” But McBryde was also eager to establish a regional chronology and she searched for older, stratified sites, where evidence of human occupation had built up over millennia. On her initial survey in February 1960 she came across a series of overhangs in a low outcrop overlooking the Clarence River at Seelands near Grafton. The sandstone walls bore clusters of cryptic engravings, the roof of the main shelter was stained by smoke and animal bones, shell fragments and debris from tool-making lay scattered on the sloping sandy floor. She returned to Seelands to excavate in August, and again the next year, uncovering a dynamic history of occupation over the past 6000 years. She also continued to survey the surrounding area, finding axe-grinding grooves and rock art nearby, and collecting the stories and stone tools amassed by the landowner, Mr O’Grady, during his time in the area.

In this slow, thorough way she progressed across the coastal plains, excavating middens, recording rock art, and mapping stone working sites at Evans Head, Station Creek and Moonee, before taking the survey onto the tablelands and western slopes, where she dug sites at Bendemeer, Graman and Moore Creek. She could be ambitious about the scope of the study because she intended it to be an open-ended, collaborative departmental program. A year in she took it on as her PhD under the supervision of John Mulvaney and Russel Ward.

Excavation and survey work took place during university vacations and on weekends. McBryde relied on her students and her colleagues (especially Mary Neeley) as field assistants, and marvelled at their intellectual and physical ability: “They could drive trucks, mend fences and dissuade curious bulls from exploring the trenches… All this, of course, provided there was a transistor radio between the sieves and the trenches so no one missed an episode of [American soap opera] ‘Portia faces life.’” McBryde gained a reputation among her students for her warmth and kindness, as well as her “nerve and nous.” She was hands-on and hardworking, with the uncanny ability to emerge from a day in a dusty trench, in Sharon Sullivan’s words, “clean, well-groomed, with lippy in place and radiating energy and goodwill.”

Her field notebooks are similarly immaculate, with detailed observations and ideas executed in impeccable handwriting. She was organised, precise and thorough, and she understood that good food was essential to the success of any fieldwork. She purchased a Rice Bros horse float and refitted it as a mobile field lab with a sink, a stove, a cupboard, a drawing board, water tanks and material to transform it into a darkroom for developing photos. It became known as “the soup kitchen” and she towed it along the small, winding New England roads behind her Land Rover, “Telemachus.” She called on a colleague, Professor Ian Turner, to look up the rations for the British army in Mesopotamia in the first world war, and used that as a catering guide for fieldwork.

Alongside the field survey, McBryde and her students pored over regional historical records, analysed early photographs and trawled through word lists for insights into Aboriginal culture and traditions. She was haunted by the collision of cultures captured in the colonial archive and later wrote about some of the witnesses to this transformative period, such as early anthropologist Mary Bundock and photographers John William Lindt and Thomas Dick. As she reflected in 1978, “It seemed unwise when attempting to reconstruct culture history to ignore the evidence of observers of tribal life at the time of its passing, in the last few decades of its prehistory.” While she found such documentary sources illuminating, she also acknowledged their limitations as a lens through which to view the deep past: “The ethnographic present may always haunt the archaeologist in this continent, both inspiring and constraining interpretation.”

What emerged from her study was a clear, cultural distinction between the societies that lived in the coastal river valleys and those that roamed the tablelands and western slopes over the last 9000 years. The differences in rock art, ethnography and artefact groupings — or “assemblages” — underlined the isolation of the two cultural groups, with the steep escarpment of the plateau and the poor high country of the tablelands acting as a “barrier” between them. It showed that while Australia may be a continent, it is made up of many countries.

Yet despite this barrier, McBryde found some rare raw materials — such as axes made from andesitic greywacke — scattered across the whole region. Along with geologist Ray Binns, she investigated the origin, distribution and composition — or petrology — of these stone axes, and together they unravelled a remarkable map of how people had moved and traded across the landscape over several thousands of years. They were able to trace, for example, greywacke stone axes found in excavations at Graman in northern New South Wales to a large axe quarry 200 kilometres away on Mount Daruka, Moore Creek, where greywacke lies cracked in heaps along the ridgeline in sight of Tamworth. McBryde’s breakthrough was to view these trade routes as more than “purely mechanisms for the distribution of raw rare materials.” By considering the social and ceremonial aspects of the stone axe trade, and the “ritual cycles of exchange,” she could glimpse webs of connections and interactions, past social affinities and mythology. She had found the shadow of a complex system of exchange that was intimately entwined with the symbolic construction of the landscape.

“Nobody,” Mulvaney reflected in 2005, “had previously traced and explained the dynamics and social determinants of exchange networks using science, linguistics, anthropology and ethnohistory.” It was groundbreaking international work, coming alongside Colin Renfrew’s famous study of obsidian networks in the Aegean, and it emphasised the magnitude of the insights that could emerge from the minutiae of local, regional research. McBryde later continued her work with axes at Mount William quarry in Victoria, where she mapped a great network of exchange that saw greenstone axes travelling over 1000 kilometres across southeastern Australia.

The significance of such vast, sprawling “chains of connection” cannot be overstated. “In theory,” Mulvaney mused, “it was possible for a man who had brought pituri from the Mulligan River and ochre from Parachilna to own a Cloncurry axe, a Boulia boomerang and wear shell pendants from Carpentaria and Kimberley.” These exchange networks brought to the fore the intimate knowledge Aboriginal people have of the land and its resources, and the interconnectedness of their societies across the continent. They also provided an archaeological signature for an oral phenomenon: the travels of ancestral beings in the Dreaming, and the epic songs they left in their wake.

By the time McBryde finished her thesis in 1966, archaeological investigations were being carried out in every Australian state and Aboriginal archaeology was being taught as a university subject in Melbourne, Armidale, Sydney and Brisbane. “Miss McBryde’s vigorous one-woman band” was gradually gaining the attention of this growing archaeological community. As Mulvaney announced in 1964, “I feel that the model for us to follow is provided by Miss McBryde’s patient survey and record of all aspects of New England prehistory.”

But although Mulvaney and Jack Golson fostered a strong program of regional research at the ANU, McBryde lamented that most archaeology in Australia continued to be “based on the evidence of a small number of excavated sites, widely separated in both space and time.” Why, we must wonder, did large-scale regional surveys not take on in Australia, considering the insights into land use that McBryde had demonstrated with her work on New England? The changing political landscape of the 1960s and 1970s had a part to play. With the dramatic shift in control that followed the rise of the Aboriginal land rights movement, archaeologists faced new challenges negotiating access to sites on Aboriginal land, let alone surveying large swathes of country.

Gender was also undoubtedly a factor. Although men also mapped landscapes and women led grand stratified excavations, these activities carried gendered assumptions, attitudes and behaviours, which changed the way they were valued. There was little prestige in survey work, while the search for the oldest and most spectacular finds was caught up in the machismo of “cowboy archaeology.” Sylvia Hallam, another pioneer of the regional model, raised this point in 1982 when reviewing Josephine Flood’s survey of the southeastern highlands. “Are only women sufficiently tough, conscientious and foolhardy to collect and analyse such a mass of trivia, and hammer it into meaning and shape?” she wryly asked.

In 1974 McBryde moved to the ANU, where she became increasingly concerned with promoting an inclusive approach to Indigenous heritage. She saw an urgent need to empower Aboriginal people to tell their own stories and to create mechanisms through which they could control their own heritage. Through her roles on the Australian Heritage Commission, the World Heritage Committee and the UNESCO advisory body, she argued for legislation that recognised the significance of whole landscapes, the inseparability of natural and cultural heritage and the intangible values of connections to country. This advocacy has had a profound role in shaping Australian and world heritage conservation practice. McBryde’s proudest achievement, however, is the number of Aboriginal students she has helped become archaeologists.

In 1991 McBryde returned to New England and walked the land as she once had done. She revisited familiar places on the tablelands and across the coastal plains, and met and talked with residents, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. As she moved across the landscape, wandering through rich subtropical valleys and densely forested steep terrain, she was followed by a story. Helpful locals told her of a woman who had come to look at the archaeology in the region long, long ago, “maybe last century.” She gradually identified the woman as herself. Her work had merged in local memory with that of another pioneer: nineteenth-century anthropologist Mary Bundock. She had entered the lore of the land.

McBryde first encountered Bundock’s name in 1968 while trawling through the Australian ethnographic collection at the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden: “With intense excitement I began to realise, working through registers and cabinets, that its collection included a comprehensive regional group of artefacts from my own research area of north-eastern New South Wales.” The carefully documented artefacts, donated to the museum between 1885 and 1892, led her to their collector, the little-known Mary Bundock. Information about Bundock’s life was sparse, yet McBryde was intrigued by one surviving fragment of her writing: an eleven-page document titled “Notes on the Richmond River Blacks.”

Bundock’s ethnographic notes bore the stamp of someone who had formed close bonds with the Indigenous community on the upper Richmond River and had a knowledge of the local dialect of Bundjalung. “The Aborigines in her account are people,” McBryde noted, “not exemplars of a stage of human existence long past in the civilised European world.” She also detected in the modest, non-judgemental observations what she described as “an inheritance of concern”: “a response to the challenges of living on the pastoral frontier, of facing the responsibility of being dispossessors.” That same inheritance has shaped McBryde’s life and values; it underwrites the inclusive, social approach to archaeology she has advocated since the 1960s. Her routes across the landscape linger today, sustained in fragments of text and memory, casting light upon the shadows of a haunted country. ●

This is an extract from Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia, published this month by Black Inc., and full references are provided there.