Updated, with new material on the response to the jailing of two police officers, on 28 February 2017

Is the impasse finally being broken in Hong Kong? Some candidates for next month’s election of the city’s new chief executive would have you believe so, as they release policies aimed at bringing harmony to a city that has been politically polarised since the Umbrella Movement protests in 2014.

When that movement for fully democratic elections ended without result after seventy-nine days, some young protesters, angered by the lack of any concessions from the government in Beijing, turned to other strategies. Hong Kong has since seen the rise of “localism” – a focus on a city identity distinct from that of China – along with calls for self-determination rarely heard since the return to Chinese rule in 1997. Some localists launched angry protests against daytripping shoppers from across the border in mainland China, whom they accused of driving up rents in the city; others clashed with police in a row over street trading in early 2016.

Continuing evidence of China’s tightening grip on Hong Kong has only fuelled the backlash. Of particular concern has been the disappearance to the mainland – or abduction, as many in the city believe – of several booksellers associated with Hong Kong’s Causeway Books, which published and sold books claiming to reveal scandals in the private lives of China’s leaders. These worries were compounded in January when Chinese billionaire Xiao Jianhua was escorted from his Hong Kong residence to the mainland by a group of men thought to be acting on orders from the Chinese government.

Some young activists are now calling for independence from China, prompting a furious Beijing to label them as traitors. The government barred six localists from running as candidates in last September’s elections for Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, or LegCo, reportedly because of suspicions that they supported independence. Yet public anger saw six others win election on a record turnout, with localist candidates taking an overall 19 per cent of the popular vote and more moderate democrats losing votes and seats.

The political temperature rose further after two of these new legislators changed the words of the oath at their LegCo swearing in, in one case cursing China. When legislature president Andrew Leung ordered them to retake their oaths, pro-government legislators walked out to prevent them doing so. The Chinese government’s subsequent intervention, ruling that the legislators could not retake their oaths, only added to a sense among democrats that Beijing was no longer willing to tolerate the “high degree of autonomy” it had promised the city in 1997.

Add to this the government’s attempts to disbar several other legislators, a recent attack on one of them at Hong Kong airport, the banning of a film seen as critical of China, and the filibustering of government bills by angry democrats in the city’s legislature, and you have an unusually febrile atmosphere. One commentator recently described it as “akin to a cold war.”

Yet a superficial glance at the campaign for the new chief executive might suggest that some of the bitterness is fading. For one thing, current chief executive C.Y. Leung isn’t standing for re-election. Leung took office in 2012 promising to unite all sectors of society, but many have blamed him for sparking the Umbrella Movement protests by allowing police to teargas unarmed pro-democracy demonstrators, a move that brought many previously apolitical residents onto the streets.

Leung’s loyalty to Beijing and seeming disdain for Hong Kong’s relatively democratic norms – he famously suggested that full democracy would give the poor too much say – alienated many residents. His plunging popularity, down to just 23 per cent in the latest polls, is summed up by the fact that many in Hong Kong, including some pro-business and traditionally pro-Beijing groups, have embraced a simple formula for an acceptable successor: ABC, or Anyone But C.Y.

Despite all this, it was widely expected that Leung, whose thick skin seemed to match his political ambition, would run again this year. Announcing his decision not to do so, he cited family reasons – his daughter has been in hospital – yet many observers saw the move as a sign that Beijing may be seeking to calm tensions in Hong Kong. (China may also reward Leung’s loyalty by giving him a senior post on a central government advisory body.)

“Of course it was Beijing’s decision,” says Jean-Pierre Cabestan, head of the Department of Government and International Studies at Hong Kong Baptist University. Cabestan argues that China’s leaders “can’t ignore” public opinion in Hong Kong, however suspicious they may be of it. “C.Y. had become a liability for the central government,” he says, “particularly after the LegCo election in September 2016 and the subsequent clumsy management of the pro-independence LegCo members.”

Those competing to replace Leung have certainly done their best to woo the public with soothing messages, not least pledging to heal the underlying economic divisions contributing to anger and disillusionment among the young.

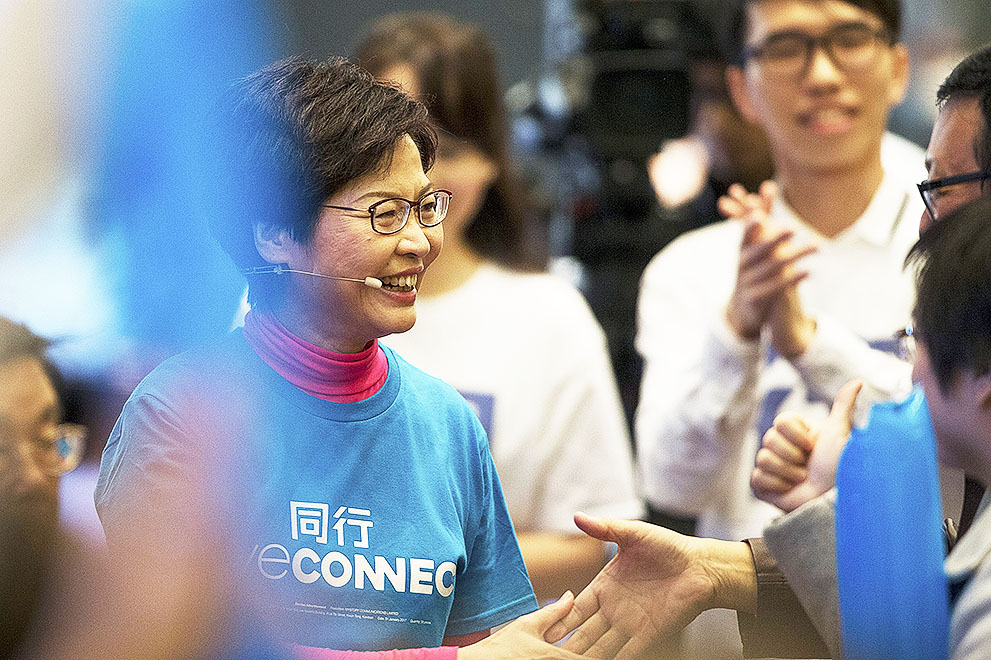

There’s Carrie Lam, former second-in-command to Leung, promising to spend more on education, help small-to-medium enterprises, and subsidise housing for young people struggling with some of the world’s most inflated property prices. (She would do the latter partly by allowing building on some of Hong Kong’s large, and long-sacrosanct, country parks.)

There’s John Tsang, Hong Kong’s financial secretary for the past nine years and long seen as a fiscal conservative, who is now offering an even wider reaching scheme to provide public housing to 60 per cent of the population, and seeking to reach out to democrats with promises to push ahead with greater democratisation.

There’s Regina Ip, once a hardline security secretary, also offering to relaunch political reforms. And there’s even veteran rebel MP “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, who once called for a boycott of the process of nominating a chief executive but has now announced he might run if enough citizens back him online.

The recent jailing of seven police officers for the televised beating of a pro-democracy activist during the Umbrella protests also hinted at some kind of closure. Police aggression at the time shocked many citizens who had previously retained faith in “Asia’s finest.”

Yet few expect the wounds in Hong Kong society to be so easily healed. For one thing, Hong Kong’s police have said they may appeal against the jailing of the officers, and more than 30,000 serving and retired police officers held an unprecedented public rally in support of their jailed colleagues in what one participant described as “the largest single gathering of police officers the world has ever seen.” The son of a late Chinese general poured oil on troubled waters by offering a cash reward for anyone who beat up the judge who jailed the policeman.

More broadly, implementing meaningful economic reforms will be no easy task in a society dominated since the days of British rule by tycoons, many of whom derive much of their wealth from real estate and have no interest in seeing property prices fall. Leung, who formerly worked for a real estate company, was quick to criticise John Tsang’s plan to promote public housing, warning that by withholding land from developers he would push up prices on the commercial market even further. Leung’s own failure to deliver on pledges to bring in social reforms, such as limits on working hours and a boost to pension rights, also highlight how hard change will be.

“I think that no chief executive in Hong Kong can really embark on reducing inequalities: blatant social inequality is part of Hong Kong DNA,” says Baptist University’s Cabestan, adding that this is “well accepted… What is less accepted has been the substantial reduction of social programs since the [1997] handover, in terms of affordable housing in particular. To be honest,” he adds, “C.Y. Leung has done better than his predecessors, but he has not gone very far: without the tycoons’ support, how can any chief executive operate?”

There’s one other crucial consideration. To win the post of chief executive in an election system that remains unreformed, candidates still need Beijing’s backing.

In 2014, the Chinese government offered political reforms including “one person, one vote” for the 2017 chief executive election – but only with a limited slate of pre-approved candidates, who would all, it was assumed, be acceptable to China. Many of the Umbrella protesters denounced this as “North Korean–style universal suffrage” and called for unrestricted choice. After the protests failed to win any concessions, democrats in Hong Kong’s legislature expressed their anger by vetoing Beijing’s reforms.

This has left the electoral process back at square one, with the chief executive, as in previous years, to be chosen by a committee of just 1194 people from different sectors of Hong Kong society. A minority of them come from democratic parties and traditionally liberal groups such as social workers and educators, but the majority come from pro-Beijing parties and social groups.

Beijing is reported to have confirmed its support for Carrie Lam, seen as loyal and a safe pair of hands, in a recent meeting between China’s top legislator, Zhang Dejiang, and pro-China Hong Kong delegates. Lam was once popular in Hong Kong, and may benefit simply from “not being C.Y.” but observers say she has been hit by her years as the public face of the Leung administration, and any candidate with China’s endorsement may struggle to win support across the board in such a polarised society.

Opinion polls routinely show around 40 per cent support for pro-Beijing groups, with a similar or higher number demanding greater democracy. The Leung administration’s efforts, until last year, to prosecute Umbrella Movement activists, and its continuing attempts to have four more legislators – including former student leader Nathan Law, and veteran democrat “Long Hair” himself – kicked out of the legislature have arguably only increased the divide.

No wonder, then, that Carrie Lam’s recent attempt to garner popularity by announcing plans for a new museum to house treasures from Beijing’s Forbidden City appeared to backfire. She was criticised both for her closeness to Beijing and for allegedly working on the project before public consultations were complete.

Similarly, John Tsang, despite his overtures to liberals and his lead over Lam in public opinion polls, is still regarded with suspicion by some for his role in Leung’s government. Tsang might also be hobbled by his apparent attempt (which he later sought to play down) to make himself acceptable to Beijing by reviving plans to introduce a controversial national security law, which was shelved after angry public protests in 2003.

Anson Chan, Hong Kong’s chief secretary under its first postcolonial chief executive Tung Chee-hwa, says that in Hong Kong’s “increasingly divided society… unlike in the old days, you’re not even able to sit down and discuss issues, and agree to disagree, without coming to blows.” She puts the blame squarely on Leung, who she says has gone “out of his way to talk about things that divide the community.” (Indeed, some critics have argued that it was Leung himself who stirred up the independence debate by picking up on, and attacking, an obscure student article referring to the topic, causing a backlash among localists.)

The atmosphere of suspicion is such that divisions in the democratic camp have grown too. Some older democrats have accused the two localists involved in the oath-taking controversy of being stooges of Beijing, sent to stir up hatred for liberals. “I think this [controversy] has been generated by the communists,” says Martin Lee, the retired legislator and veteran democracy campaigner. “I think these two guys [whose oaths were ruled invalid] were put up to it by someone… It’s a matter of logic.” According to Lee, who founded the Democratic Party, the pair “went out of their way – the girl in particular, she used swear words in the oath… insulting the whole Chinese nation. Now who would do that, unless there’s another motive?”

Others simply accuse the young activists of naivety – or egotism. Hong Kong’s last British governor, Chris Patten, a long-time supporter of greater democratisation in the city, warned on a recent visit that the activists’ “extreme views” could lose the “moral high ground” they had gained with the non-violent Umbrella Movement. They risked “diluting the campaign for democracy,” he said, “by arguing for independence.”

But Sixtus “Baggio” Leung, one of the two elected legislators disqualified over the oath-taking, says the pair simply wanted to speak up for Hong Kong, and thought that such behaviour had been tolerated before. Leung – no relation to C.Y. – says he has nothing against the people of China, but is adamantly opposed to the nation’s government. “I hate the People’s Republic of China,” he says. He argues that Hong Kong’s younger generation has been backed into a corner by what he sees as the hard line taken by Beijing and the Leung administration in relation to the promises of greater democratisation made at the time of the handover in 1997, as part of China’s “one country, two systems” formula for governing Hong Kong.

“If you look back to 1997, at that time our economy was not very good, but no one would yell for Hong Kong independence then,” he says. “So why, in 2016, when theoretically we are richer, are people doing this? Something happened, especially during the last ten years: Beijing is destroying our system and restricting our freedom.” Leung cites the Causeway Booksellers case, the disqualification of election candidates, the oath-taking row and Beijing’s subsequent intervention as examples. “These incidents have proved that ‘one country, two systems’ seems to have failed… The government is trying to use any way they can to destroy Hong Kong’s system, [its] separation of powers, rule of law. Do you still think that the so-called ‘moral high ground’ can defend or protect core values or rule of law, or [fight for] true democracy in Hong Kong?”

Jean-Pierre Cabestan says such a sense of disillusionment is increasingly common among young people – including students at his university, who recently used a graduation ceremony to criticise Beijing’s ruling on the oath issue. Many young people “don’t seriously want independence, but they’re just so angry,” he says, not least at Beijing’s “conservative” approach to political reform in Hong Kong. (Not only has it sought to limit the choice of chief executive candidates, but it has maintained the “functional constituencies,” or professional groups, that not only dominate the CE selection committee but also account for half the seats in Hong Kong’s legislature.)

“Some decided to push for independence not because they want independence per se, but because they want to send Beijing a very clear signal that it’s not kept its promises, and has actually frozen any kind of project for full democracy,” Cabestan says. This trend was highlighted by when an opinion poll last year suggested that more than a third of citizens aged between fifteen and twenty-four supported independence for Hong Kong.

This radicalisation has only added to the gap in understanding between the younger generation and Hong Kong’s older democracy activists, says Cabestan. While the latter group were galvanised by the Tiananmen protests in Beijing in 1989 and “cares about mainland China’s future – their final objective is the democratisation of all China,” he says that the young activists “only care about Hong Kong,” and often feel, rightly or wrongly, that the older generation has failed to push hard enough for political reform.

Beijing might well be happy to see the democratic camp fragmenting. But it is clearly alarmed by the rise of “hotheads” and growing calls for independence, along with other gestures such as the flying of colonial-era flags by some activists. And while it doesn’t wish to see chaos in Hong Kong, and may be seeking a more conciliatory chief executive, its apparent backing for Carrie Lam suggests that, even in an election that is likely to be contested only by candidates broadly loyal to China, the mainland leadership can’t restrain what many in Hong Kong see as its tendency to meddle in the city’s affairs.

The desire to control Hong Kong, where non-government and religious organisations are far more active than in mainland China, has increased since Xi Jinping became China’s top leader in 2012, according to Cabestan. “He wants to prevent Hong Kong becoming a base for subversion [of the mainland],” he says, noting that a number of Taiwanese political figures have also been banned from entering Hong Kong in recent years. “What they dislike the most is the growing cross-fertilisation between Hong Kong and Taiwan activists.” Xi’s aim, Cabestan suggests, is “to ‘Singaporise’ Hong Kong… to control the polity much more, but to keep the economy and courts independent as far as business cases go.”

There’s no doubt Beijing is now exerting greater control over Hong Kong’s media – with mainland-related companies holding stakes in or controlling major players including the main free-to-air broadcaster TVB and the South China Morning Post. Yet the media remains more open than that of the mainland and, despite China’s influence, Cabestan suggests Hong Kong’s “democratic culture” will be hard to shift, with the young less influenced by mainstream media. “They use social media to communicate, they read what they want,” he says. “So you get all these kids agitating – and that’s what worries Beijing.”

It’s worth noting, too, that revelations in Hong Kong’s media dealt a fatal blow to the campaign of Beijing’s preferred candidate for chief executive in 2012, Henry Tang, giving C.Y. Leung, originally an outsider, the chance to win.

And while some of those in Hong Kong who are more actively opposed to China may ultimately vote with their feet – one recent poll suggested that some 40 per cent of the population, and 57 per cent of eighteen-to-thirty-year-olds, would like to leave the city – many say they won’t leave, or simply can’t afford to. In a city that remains “on the frontline between liberal democracies and authoritarianism,” as Cabestan puts it, that means tensions are likely to continue.

Whether any candidate can win Beijing’s approval while smoothing over at least some of these tensions remains to be seen. Carrie Lam sought to play down divisions over policy by announcing, unusually, that she wouldn’t unveil her full platform until the formal election process begins in early March, stressing that “governance is not only about a manifesto. It is more about my heart, my attitude and integrity.”

Many in Hong Kong are hoping for less confrontational leadership, but winning hearts and changing attitudes may not be so easy in a city where even definitions of political integrity have become polarised. •