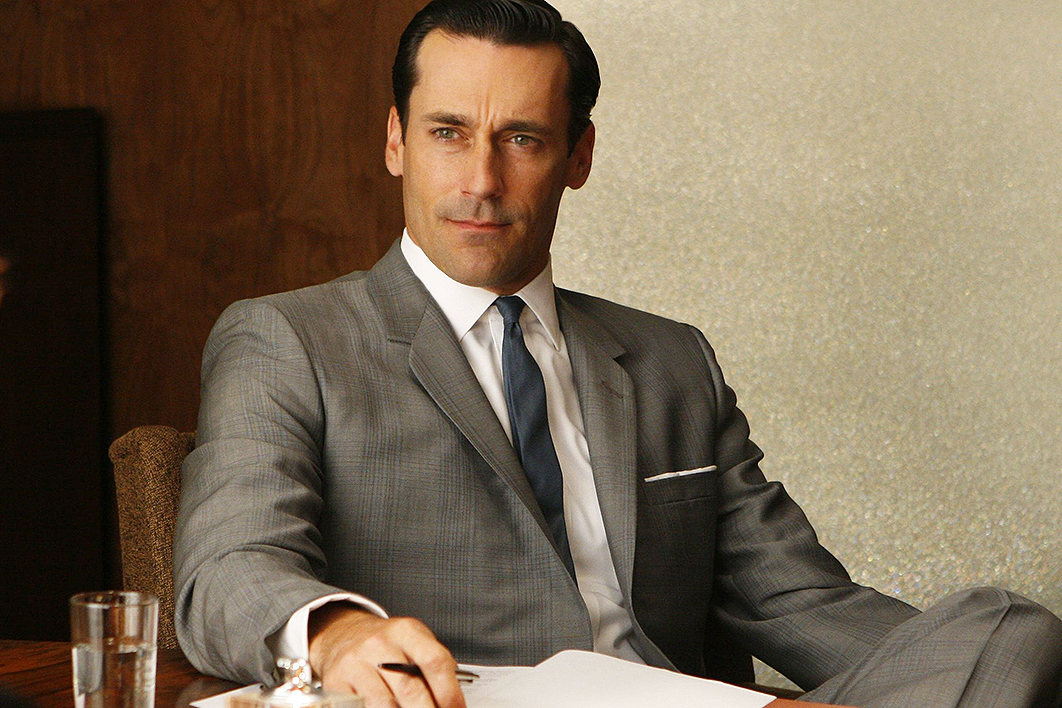

BY NOW, most Mad Men devotees living outside the United States will have bought and watched Season 4, screened there in 2010. Set in a Madison Avenue ad agency on the cusp of what baby boomers remember as the liberating Sixties, Mad Men has won a string of awards; so has lead actor Jon Hamm for his portrayal of Don Draper, creative director of Sterling Cooper. Yet, in my experience, even its fans disapprove of Mad Men, which they regard as a historically accurate but morally ambivalent portrait of the bad old sixties.

Taking the show to task in the New York Review of Books earlier this year, the American critic Daniel Mendelsohn said that, watching the first series, he found “the characters and their milieu… unrelentingly repellent,” the action, “the stuff of soap opera.” “What is supposed to give [Mad Men] its higher cultural resonance is the historical element,” he says, but this is undermined by the show’s “hypocrisy”: “it’s simultaneously contemptuous and pandering.” In a follow-up letter in the New York Review, Mendelsohn stressed that his objection to the series “was made on structural and aesthetic not historical grounds.”

Well, I want to praise the series on structural and aesthetic not historical grounds, and to do so, I want to suggest another prism through which to view it: The Great Gatsby.

Consider first the similarities between Don Draper and Jay Gatsby. Jimmy Gatz, born in the Midwest, runs away from home, reinvents himself as Jay Gatsby, joins up and, after the Great War, makes his fortune working with a bootlegger. Don Draper, born Dick Whitman in the Midwest, assumes his dead buddy’s identity in Korea and, after the war, makes his fortune as an advertising executive. Both have a conscience about their life of deceit. When Gatsby buys his mansion, he also buys a house for his father. Draper, forced to come clean to the real Mrs Draper, buys her a house.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel is such a knockout aesthetically that its brilliant structure, as a thriller, can be overlooked. Think of how Fitzgerald builds – through a succession of distorted, mesmeric scenes among the rich on Long Island, the sleazy in New York, and at the gas station overlooked by the sinister eyes of Dr T.J. Eckleberg – to, first, the fatal car accident, and then the absurd death of romantic, chivalrous Gatsby on a blow-up mattress in his swimming pool. The overall effect is dark, tragic.

So it is with Mad Men. The sets are often dark, garish and claustrophobic. The sixties are shown to us distorted, almost grotesque, as in the over-upholstered, cinch-waisted women, and especially in the “battle of the sexes.” The recklessness of these chain-smoking, hard-drinking, serial adulterers, the callousness of their demeaning treatment of their wives and secretaries, its effects on the women themselves, is beyond shocking. So worldly Joan sends ambitious virginal Peggy on her first day at Stirling Cooper to be prescribed the brand-new Pill, readying her for the inevitable sexual advances of a predatory adman. Like the desperate party-going adulterous rich in The Great Gatsby, they’re all going to hell in a handcart. At the same time, they are vulnerable and, like Peggy’s priest, we care about them. •