On 17 August 1942 Ulrich Boschwitz, a twenty-seven-year-old German-Jewish writer, departed Australia for Europe aboard a British ship, the Abosso. Nearing the end of its journey, in the dangerous wartime waters of the north Atlantic, the vessel was torpedoed by a German U-boat. Boschwitz was among the 362 passengers and crew who perished. An unpublished manuscript of his was lost forever, and even his published work, now long out of print, seemed fated to leave scarcely a trace.

Three-quarters of a century later, Boschwitz’s novel Der Reisende (The Traveller) has been published to great acclaim in Germany. Rediscovered and re-edited, it is a work of great historical significance that deserves to be translated into other languages and read by a wider audience.

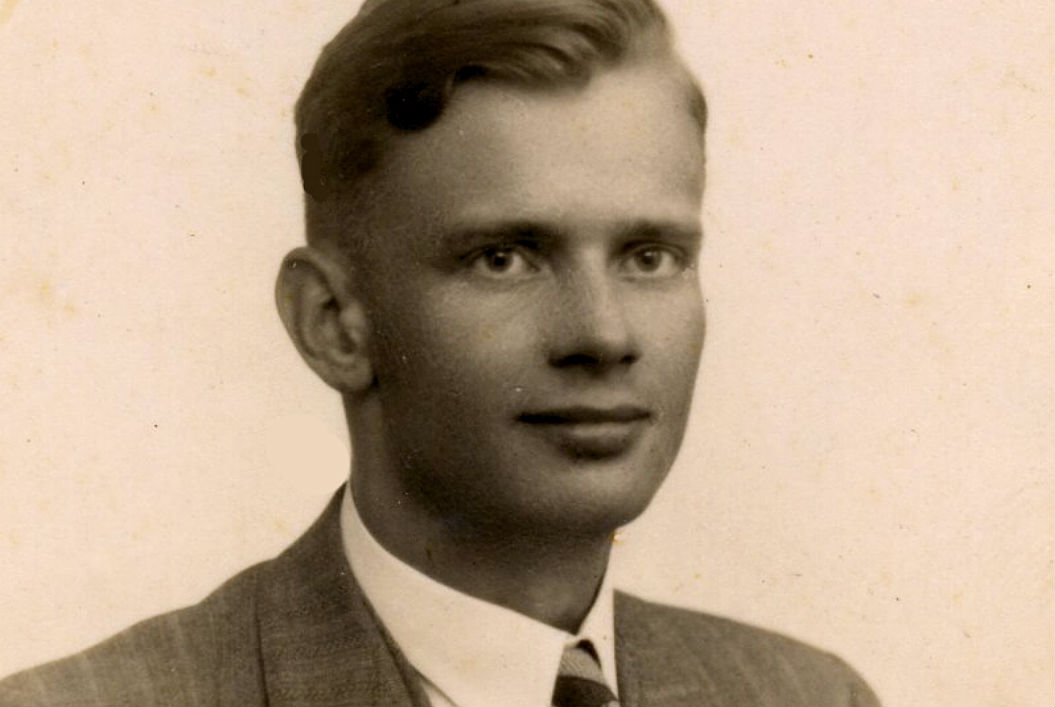

Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz was born into an affluent German-Jewish family in Berlin in 1915. His father, Sally, was a factory owner who died shortly before Ulrich was born. His mother, Martha, came from a leading Lübeck mercantile dynasty, the Wolgast and Plitt families. After Sally’s early death Martha, an amateur artist, took over the running of the business. Ulrich undertook a business apprenticeship after completing school and seemed destined to take over the business.

Hitler’s rise thwarted that plan. On 1 April 1933 the National Socialist regime declared a national boycott of Jewish businesses and life soon became extremely difficult for German-Jewish families. Ulrich’s elder sister, Clarissa, emigrated to Israel in 1933, and Martha and Ulrich left the country two years later. They had no choice but to leave the family fortune behind.

They went first to Sweden and then to Norway, where Ulrich wrote his first novel, Menschen neben dem Leben (People Next to Their Lives). Sweden was important for exiled German writers — Thomas Mann was among the authors whose work was published there — and Boschwitz’s first novel appeared there in Swedish 1937 as Människor utanför. He used the pen name John Grane rather than the very German Ulrich Boschwitz.

The novel was a success and Boschwitz was able to move to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. During the late 1930s he moved between France, Luxembourg and Belgium, completing The Traveller in 1938 while watching from Brussels as the persecution of Jews intensified after Kristallnacht. Like his first novel, The Traveller was published under his pen name and in translation, this time in English. It appeared in England in 1939 as The Man Who Took Trains and in 1940 in the United States as The Fugitive. A later French translation used the title Le fugitiv (1945).

The outbreak of the second world war destroyed any chance of the novel’s being a commercial success. It soon went out of print and copies are now only available in rare book collections.

By the time the war broke out Ulrich and Martha had made their way to England. There, on 28 June 1940, as fears of a German invasion reached fever pitch, they were interned as enemy aliens. Two weeks later Ulrich was deported to Australia on the transport ship the Dunera. Martha remained in internment on the Isle of Man.

The Dunera is notorious for the dreadful treatment of the passengers by the British troops. The troops rifled through the internees’ belongings and cast overboard anything they considered useless. Boschwitz’s manuscript of a new novel, Das grosse Fressen (The Big Feed), was lost in this pillaging.

Boschwitz spent two years in internment in Australia, first in Hay, in New South Wales, and later in the Victorian town of Tatura. Throughout, he wrote incessantly, working on another novel, Traumtage (Dream Days) and correcting The Traveller. He wrote to his mother that The Traveller was his best work and that the corrections would improve the new edition of the book, for which he had publishing contracts.

The boycott of Jewish businesses begins on 1 April 1933. Creative Commons Von Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-14468/Georg Pahl/CC-B

During Boschwitz’s two years in Australia official attitudes to the internees changed. The British government acknowledged that many of the internees were refugees and opponents of Nazism and that they had been shamefully maltreated on the Dunera. From 1941, a number of avenues for release became available to the Dunera internees. The next year Boschwitz left Australia for England.

He carried the manuscript of Traumtage with him. He told a friend that if the ship went down he would try to save the manuscript by tying it to himself under his clothes. When disaster did strike, though, neither Boschwitz nor the manuscript survived. His corrected version of The Traveller fared no better.

We know of this missing work only from his last letter to his mother, written in English to pass the censors and available in the digital repository of the Leo Baeck Institute, an organisation devoted to the history of German-speaking Jews. Boschwitz told his mother that somebody travelling on another ship had undertaken to bring the first 109 corrected pages of The Traveller to her, and that she should “get the advice of some experienced literary chap” to finalise it. “In case you get this letter,” he wrote, “you probably know why. I took my chance and failed.” The corrected pages somehow went missing.

The fact that the novel Boschwitz considered his best has been now been published in revised edition owes much to a German publisher and editor, Peter Graf, who is renowned for rediscovering lost works. Ulrich’s niece, Reuella Shachaf, alerted Graf to the existence of a typescript of the original version, in German, of The Traveller. Aware that it fell short of Boschwitz’s revised version, Graf assumed the responsibility of being Boschwitz’s posthumous editor. He familiarised himself as much as possible with Boschwitz’s life and work and edited the manuscript as he believed Boschwitz would have wanted. This, at last, was the “experienced literary chap” Boschwitz had asked his mother to seek out.

Graf described his work as a mixture of humble reverence and audacity. “You approach a text like this with awe,” he told German radio, “and you need a bit of courage at this or that point to say, okay, the author would have approved of that. You also have to trust a bit what you learnt over all the years.”

The result is remarkable. The Traveller takes us right back into the time when it was written. Turning the pages, you feel as if history is hitting you in the face.

The novel centres on Otto Silbermann, a German-Jewish businessman with a Protestant wife, Elfriede, living in Berlin in the 1930s. They are wealthy and refined and hang modernist art in their well-appointed flat. Their son Eduard is living in Paris. Until 1938 Silbermann and Elfriede live comfortably in Berlin, insulated from the increasing anti-Semitism by their privileged position and the fact that Silbermann does not look like the stereotypical Jew of Nazi propaganda.

But by the time the action of the novel begins Silbermann and Elfriede have come to regret having stayed. Hostility is closing in and they are looking to leave. Silbermann is in the invidious position of negotiating the sale of their house to an old acquaintance who has realised that there is good profit to be made from the dispossession of Jews. The negotiations are interrupted by telephone calls that signal the reality they face: first, Eduard phones from Paris with the news that he has been unable to acquire travel permissions for the couple; then Silbermann’s sister calls, distraught that her husband has been arrested and her flat ransacked. After each interruption Silbermann lowers the price for the house in line with his growing desperation. Then the negotiations cease altogether when there is the sound of fists beating against the door and the demand, “Jew, open up!”

At Elfriede’s urging Silbermann flees through the back door. He manages to escape the house only to find himself in a city taken over by marauding Nazis. The reader realises that it is 9 November 1938 and Kristallnacht is under way. Silbermann creeps through the hostile streets feeling that he has become “a swear word on two legs.” Rapidly he comes to the realisation that the Nazi regime has robbed him of both his means to live — “Nowadays one is murdered by economics,” he reflects — and of the right to exist. “Life is forbidden to us,” he tells a fellow Jewish businessman. From this point on, he is “the traveller.”

Even before he was interned as an enemy alien, Boschwitz had plenty of experience of being displaced, and he portrays Silbermann’s predicament with great insight and flashes of dark humour. In creating a sense of alienation he was clearly influenced by Kafka, and incidents in The Traveller echo scenes from the Czech writer’s fiction. At one point, for instance, Silbermann reduces his surname to one syllable, “Silb,” just as Kafka’s characters often go without full surnames. Although this is intended to make his name sound less Jewish, it makes him seem absurd because it is very similar to the German word for syllable, Silbe.

The novel also extends beyond Silbermann’s perspective to gives us a revealing social portrait. He is robbed of business capital by his partner and former closest friend, now a Nazi party member, who coldly reasons that “every person exploits their advantages. Now you [Jews] have bad luck and we [Germans] are profiting. That’s totally fair.” Silbermann encounters locals who are sympathetic to him personally but also enthusiastically support Hitler; bureaucrats who believe they are just doing their duty when they persecute Jews; a young communist who helps Silbermann despite his dislike for bourgeois Jews; foreign businessmen oblivious to the persecution of the Jews; and even an alluring divorcee who tells Silbermann he should thrive on the excitement of a life lived in tumultuous times.

Through all of this, Boschwitz shows us the degradation of German culture under the Nazis. Indeed, at one point Silbermann finds himself sharing a train compartment with two Nazi propagandists trying to make up a new German term for culture because the existing term, Kultur, is too close to other languages. Silbermann is morbidly fascinated at what tortuous word they will invent but leaves the compartment before he finds out.

As the novel moves to its climax, a relentless rhythm comes to the fore. Silbermann cannot get the rattling of the train tracks out of his head and it seems to increase in volume. The noise builds to a resounding crescendo in the vivid final scene, which borrows techniques from film to achieve its effect.

The Traveller is a wonderful rediscovery. Ulrich Boschwitz didn’t live to learn of the full horror of the Holocaust but he saw and documented its early stages with great clarity, leaving a remarkable record of those days. It combines the qualities of powerful eyewitness accounts such as Victor Klemperer’s diaries I Will Bear Witness with the broad sweep of novels about the degradation of German culture written by authors in exile, most notably Thomas Mann’s epic Doctor Faustus.

The publication of The Traveller not only revives Boschwitz’s memory but reminds us how powerfully a novel can make history come alive. It’s a major piece of literary restoration. ●