It is difficult not to be amused by the Global Times’s portrayal of Malcolm Turnbull as a loudspeaker for the United States in the Pacific. Fairfax journalist Kirsty Needham quotes one of the more comical sentences from the Chinese daily: “This [loud]speaker works very hard, and very proud, but more and more it becomes local noise, self-righteously blah blah blahing.” The obvious difficulties of translating the Chinese into persuasive English, the vulgar terms in the Chinese original (“wala wala”) and the personal nature of the invective all add to the effect. Part of the unintended humour lies in the fact that the article reads like a tirade from the Mao years: if Turnbull is a loudspeaker, Australia is “a paper cat following on the heels of the paper tiger, America,” phrases straight from the Chairman’s mouth.

The English-language edition of the Global Times didn’t carry this editorial, and the intended audience was clearly a domestic one. But the vocabulary is a reminder of what and whom Australia is dealing with in these globalised times. An Asialink blog post by Anthony Milner and Jennifer Fang, quoted by Needham in the same report, suggests the importance for Australia of joining with its neighbours in full acknowledgement of China’s leadership. But the Global Times, likely to be happy with Milner and Fang’s argument that Australia is out of step with the region on this issue, doesn’t make such a concession easy. Its editorial projects the image not of an established leader, but of an easily angered hegemon that hasn’t yet worked out how to make all its clients fall into line.

If they are well-read in their own history (and Xi Jinping certainly is), Chinese leaders will recognise the problem as an old one. When China’s first emperor was yet just one king among many, he granted an audience to the strategist Wei Liao. Wei flattered him, saying, “Qin’s might is such that the rulers of other states are like mere heads of a province or a district beside it.” The problem for such a strong state, Wei went on to say, was that these lesser states might join in league against it. He had a plan: “I hope Your Majesty will not be sparing of goods and money but will hand out bribes to their leading ministers so as to disrupt their schemes. By laying out no more than 300,000 in gold, you can completely undo the other feudal rulers.”

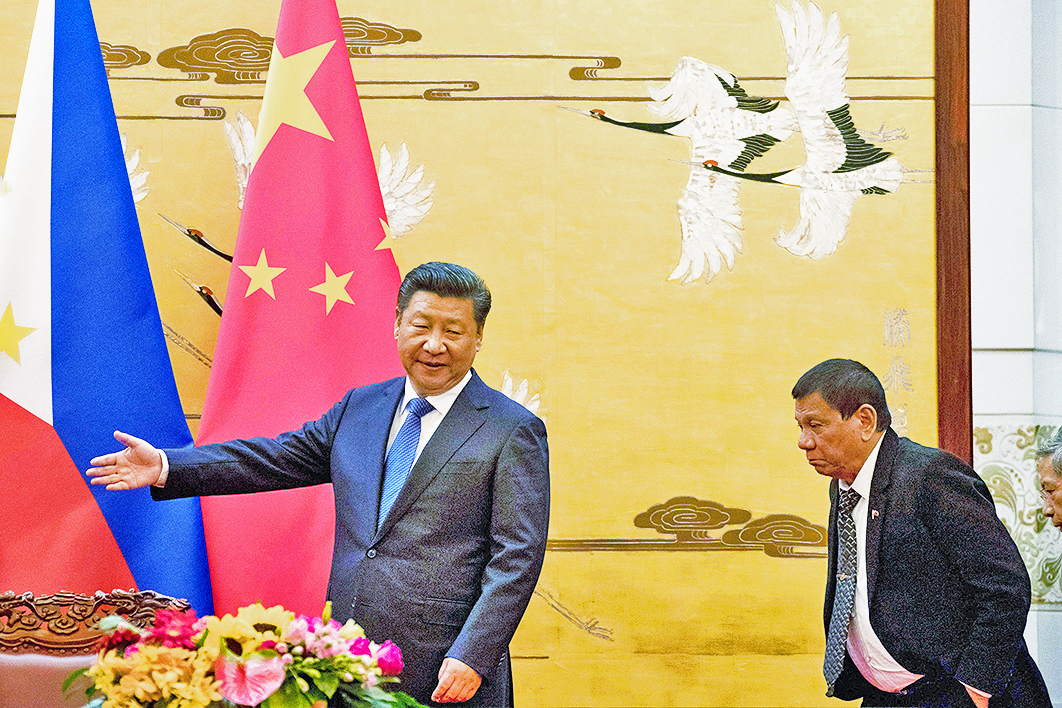

And so it came to pass. Qin followed Wei’s advice, and the surrounding states fell like flies into the trap. More than two millennia later, Beijing is following the same script. Rodrigo Duterte’s rapid transformation from a Churchill to a Chamberlain of the South China Sea is an outstanding example of how successful the strategy can be.

Most states in the region are still working out how to manage this big new power. Do they subscribe to China’s invocation of ancient historical relationships that were sundered by Western gunboats and are now, properly, being restored? Or do they stand on their dignity as modern nation-states with sovereign rights, as deserving of respect as any great power? For Australia, the question is a bit different, since it has no ancient relationship with China. Admiral Zheng did not land on these shores early in the fifteenth century, and Australians did not make their way to the capital to pay tribute any time thereafter.

Nonetheless, as is the case elsewhere, the “300,000 in gold” counts for a lot in Australia. When Milner and Fang argue that “Australia has become disconnected from its own region,” they imply that this reflects a dated attachment to the US alliance. In fact, the rise and rise of China has captured the attention of politicians, investors and educators in this country to an extraordinary degree. Influential Australian commentators here, as in Southeast Asia, have not only acknowledged China’s leadership but have been hard at work getting the rest of the country to do so as well. Bob Carr and James Laurenceson at the Australia–China Relations Institute and Hugh White at the ANU are only the most obvious advocates. Dazzled by China, Australians have lost sight of Southeast Asia in important respects. The fall-off in engagement is particularly evident in a decline of Southeast Asian expertise in our universities.

It is one thing to urge reconnection, as Milner and Fang do, and another to subscribe to an imagined regional consensus on the status of China’s leadership. Whatever Asialink knows about the attitudes of commentators in the rest of the region, it is at least clear that there is not at present a consensus on China’s leadership. Vietnam is resistant to Chinese hegemony; Indonesia is watchful; Singapore “remains a great believer in a strong US presence in the region.” Japan, which may not have entered into Milner and Fang’s analysis, seems in no present danger of being led by China. South Korea, a country that China should have been able to cultivate more effectively than has been the case, has put in place an American missile shield in face of China’s objections and threats of economic retaliation. Chinese enrolments in South Korean universities, accounting for up to half of some student bodies, have dropped precipitately in the current academic year.

China does have significant acolytes in the region, but must wish they were less flaky. The Philippines has a populist and erratic leader whose tenure is uncertain, Thailand is run by a military junta, and Malaysia’s prime minister is embroiled in ongoing financial scandal. These shortcomings in political culture at the leadership level do not mean that their cosying up to China is unimportant, or that Australia should not be engaging with the countries concerned. (In fact, this country’s current engagement with the Philippines is much in the news.) But it is open to question whether a democratic country with an anti-corruption commission and a free press should be lining up with them to pay tribute to China on the basis of regional consistency.

In an ironic historical shift, these three countries were aligned with the West during the cold war, and looked to the United States as protector, while Jakarta and Hanoi formed an “axis” with Beijing — at least until the military coup in Indonesia in 1965. Current relations are more complex. In July, Indonesia enraged China by bestowing a new name, North Natuna Sea, on the maritime zone in the northern outreaches of the Indonesia archipelago, crossing China’s sacrosanct “nine-dash line.” At the ASEAN meeting in early August, Vietnam in its turn provoked China by pressing for tougher wording in the South China Sea code of conduct.

Jakarta and Hanoi are now showing signs of wanting to strengthen bilateral ties. Two weeks ago, Nguyen Phu Trong, secretary-general of the Communist Party of Vietnam and head of the Politburo, paid a visit to Jakarta. This was the first visit from Vietnam at this level since Ho Chi Minh attended the Bandung Conference in 1955. Trong’s main presentation was delivered at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta, and focused on the need for unity in ASEAN and for resisting great power interference. He did not name the “great power,” but with the renaming of the North Natuna Sea still fresh in their minds, the audience would have understood it to be China.

Trong’s visit coincided with the fourth annual meeting of the International Conference on Chinese Indonesian Studies, held at the country’s top university, Universitas Indonesia, and attended by scholars from Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, China and (in a tiny minority of two) Australia. The theme of the conference was China’s Impact on Southeast Asia and Its Diasporic Communities. Papers by Chinese presenters in the plenary sessions, including one on Sino-Indonesian relations in the 1950s and another on China and ASEAN, provoked critical and even angry responses from the floor, expressed mainly but not only by Indonesians in the audience.

A matter of particular irritation for the audience was the supposition that China should be able to build bridges with mainstream societies (notably Indonesia and Malaysia) through its contacts with the diaspora communities. Such a strategy, defended by the speaker on grounds that it was “normal” and “understandable,” was viewed from the floor as divisive, and likely to have a negative impact on the Chinese ethnic communities in Southeast Asian countries.

It is not easy being a scholar in China. In international contexts in particular, there is a strong expectation that the interests of the country (in other words of the party-state) be defended in any academic presentation. In 2014, Xi Jinping embarked on a soft-power strategy of “telling the China story well.” Since then, academics in Chinese universities have been undertaking training (“brain-washing,” in their own words) in how to tell the China story. Not surprisingly, the senior academic in the Chinese delegation at the conference segued in his presentation from history to policy, urging the importance of ASEAN unity. Needless to say, the premise for this piece of advice differs from Nguyen Phu Trong’s.

China is demonstrating an ability to divide and rule ASEAN, particularly through its relations with Malaysia and Singapore. But Beijing is used to dealing with orderly hierarchies and prefers not to be in the position of herding cats; what it would ultimately like is its own Monroe doctrine in the Asia-Pacific region. Australia is far from being the only country in the region resisting this prospect. For this among other reasons, stronger connections with its neighbours seem desirable. The mere promise of military aid in times of crisis (as currently with the Philippines) is woefully inadequate. But these is no obvious reason why closer relations should entail capitulation to an authoritarian regime in the interests of regional conformity. Diversity, too, can be a source of strength that needs recognising and protecting. •