Every other day the web page of the world’s number one search engine features a cute cartoon to celebrate something like World Chocolate Day or the woman who invented potato flour\. It’s designed to make Google look like a happy kingdom of approachable hipsters, rather than a company with — how should I put this? — a mixed reputation for its treatment of consumers and competitors.

Back in January 2012, the US film and music industry promoted a bill before Congress called the Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA. It was designed to crack down on search engines like Google that link to sites that host or facilitate the trading of pirated content. What could be wrong with protecting the intellectual property of hardworking songwriters, musicians and film-makers, you might ask? Well, plenty, according to Google, which makes lots of money by redirecting consumers to pirate sites.

The day after SOPA was announced, the cute Google graphic was blanked out by a large black rectangle and a little caption that read, “Tell Congress: Please don’t censor the web!” This image was seen by 1.8 billion people, and soon the inboxes of Congress were overflowing with emails. Within a week, the bill had been withdrawn.

Google spends more than US$15 million annually on lobbying the US government. What it wants, it usually gets. But in this case, Google barely spent a cent; it used the massive dominance of its brand as a trumpet call to attract the people to its banner. And they came; despite the fact that they’d been duped.

As the diehard Google critic and former film and music producer Jonathan Taplin has written, “The very notion that getting Google to stop linking to criminal pirate sites constituted censorship is an exercise in Orwellian doublespeak.” These days we call it “fake news.”

Facebook and Google are so embedded in our lives it’s hard to remember what life was like before their arrival. (Google appeared in 1998, and Facebook was launched in 2004 — I know because I googled it.) It’s such a short time — just a couple of decades. In that blink of a modem light, Big Tech has transformed large chunks of the economy — in retail, the media, advertising and the arts. It has hoovered up the value created by these so-called heritage industries and redirected the treasure into super profits, vainglorious philanthropy, dreams of space travel, job-destroying artificial intelligence, and the search for eternal life.

It’s all happened so quickly, we’re only just starting to understand what it might mean.

When Google called for help from the masses five years ago, they willingly stormed the digital barricades. Would they do it again in 2017? Maybe not, because there’s a growing view that Big Tech is not always the consumer’s best friend.

Alphabet, the company that owns Google, controls 88 per cent of the search advertising market and owns potential competitors like Admeld, DoubleClick and AdMob. Facebook — which has also bought out its potential competitors Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger — has sewn up three-quarters of the world’s mobile social traffic market. Together, these two companies accounted for just about all of the revenue growth in the US digital advertising market last year. Alphabet’s net income in 2016 was US$19 billion; Facebook’s was US$10 billion.

The high-tech tycoons — Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin — are our century’s equivalent of John D. Rockefeller. And their modern-day monopoly power is just as likely to generate the sort of regulatory backlash that saw Rockefeller’s Standard Oil broken up.

In a widely reported speech last year about the dangers of monopoly, US Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren hopped into Big Tech for abusing its monopoly status. Big Tech supplies the platforms that smaller companies depend upon for survival, Warren conceded, but it uses this market power to “snuff out competition.”

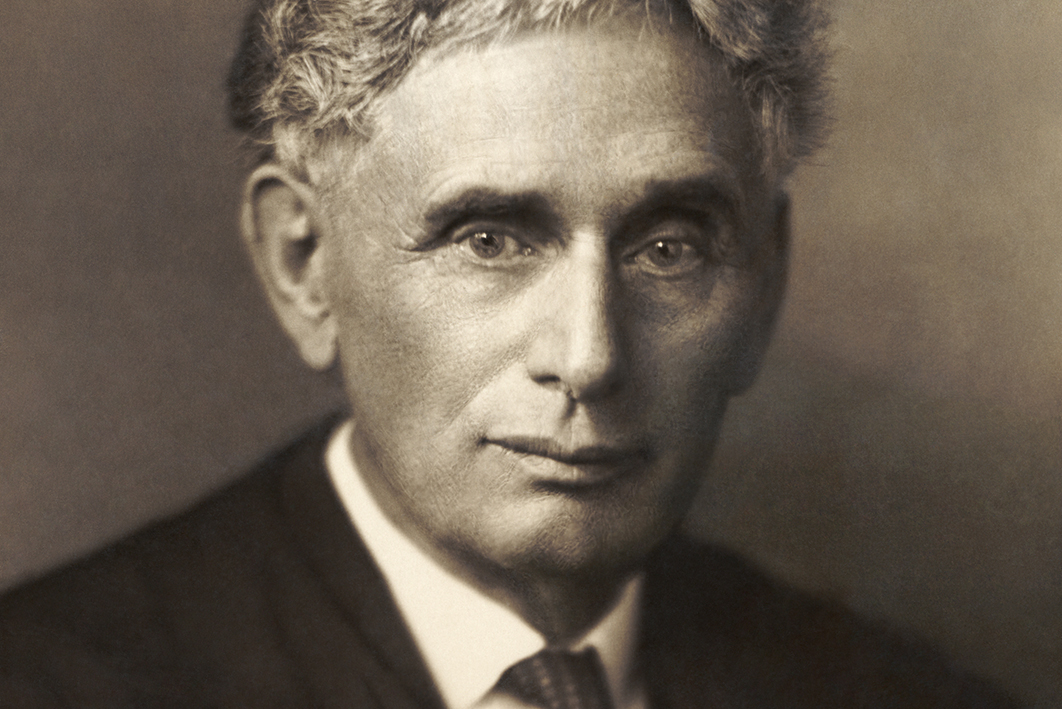

Senator Warren is the informal leader of the New Brandeisians — named for the former Supreme Court justice and one-time antitrust adviser to Woodrow Wilson, Louis Brandeis, who famously once wrote, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

Paid-up members of the movement include the former journalist Barry Lynn, from the New America Foundation, who wrote Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction, and Jonathan Taplin, who recently published Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Have Cornered Culture and What It Means for All of Us. These (overly long) titles pretty much say it all: Big Tech came, saw and conquered — by laying waste to established business models, jettisoning twentieth-century notions of privacy, and actively pursuing monopoly power.

Trust-buster: Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis c. 1916. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The New Brandeisians are obviously of the left, but they’re starting to acquire some interesting fellow travellers from further along the political spectrum.

Partly out of self-interest, and partly from ideological distaste, the world’s pro-business, pro-free-market media are also getting fed up with Big Tech’s monopoly power. According to the Financial Times, “Big Tech’s grip on power needs addressing.” Not long ago, the Economist proclaimed, “The data economy demands a new approach to antitrust rules.” The Los Angeles Times recently asked, “Is it time to break up the big tech companies?”

In July, the warring tribes of the US media announced they would work together to win the right to bargain collectively with Google and Facebook over digital advertising rates. Arch competitors like the Washington Post and the New York Times are seeking a limited antitrust exemption from Congress to negotiate payment more in line with the true market value of their content. Even that well-known bastion of trade union solidarity, News Corp, is supporting the deal.

According to News Corp’s CEO, David Chavern, writing in his company’s Wall Street Journal, “The only way publishers can address this inexorable threat is by banding together. If they open a unified front to negotiate with Google and Facebook — pushing for stronger intellectual-property protections, better support for subscription models and a fair share of revenue and data — they could build a more sustainable future for the news business.”

Across the Atlantic, Google is also getting a tickle up from its many enemies and competitors courtesy of European regulators. Back in 2014, on the verge of reaching a settlement with the European competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager over a case examining Google’s virtual monopoly in internet searching, the tech giant was taken down by a corporate blitzkrieg. In an open letter to Google, right-wing press baron Mathias Döpfner, CEO of Axel Springer, took aim and didn’t miss. Döpfner linked the future of the European project to the company’s continued dominance and declared, to popular acclaim, “We are afraid of Google.”

Under the circumstances, Vestager had little option but to let the case run on, and in June this year Google copped a record-breaking fine of US$3.6 billion for abusing its effective monopoly in internet searching by sending traffic to its own shopping service at the expense of commercial rivals. Google can easily afford the fine, so it doesn’t create a great incentive to change its business practices, especially if American regulators continue to take a more tolerant view. When you’re a near monopoly, hubris is paydirt.

You might point out that Big (Old) Media is just reacting to the success of companies that have done so much to destroy its once highly profitable business model — and you would be right. But, as Senator Warren also pointed out in her speech, the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few doesn’t just affect the other big players who fall by the wayside.

New research from the Economic Innovation Group, Dynamism in Retreat, reveals a worrying trend — in the US, at least. “For the first time, the United States experienced a collapse in new business creation so severe that companies were dying faster than they were being born,” the report says. “The rate of new business has plummeted, falling by half since the late 1970s.”

The reasons are varied, but the report emphasises one in particular: market concentration. The successful firms in the US today are big, dominant and exceptionally profitable — but they’re not big job creators. The high levels of market concentration in the technology sector are just the most extreme version of the new norm. The idea that high-tech start-ups are the dynamic heart of the modern digital economy is a pop-culture furphy: young tech heads aren’t becoming Google, though they may get bought out by it.

How this battle over the concentration of economic power plays out in the fevered swamp of Trump’s White House is anyone’s guess, but as Elizabeth Warren has warned, “competition in America is dying.” To which the digital robber barons of the twenty-first century might counter, “She says that like it’s a bad thing.”

Here in Australia, Tony Boyd, the Australian Financial Review’s widely read Chanticleer columnist, says that federal MPs are aiming at a soft target when they attack the Big Four banks. “Why not show some creativity and conduct an inquiry into the other ‘big four’?” he wrote recently. “This merry quartet — Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon — are changing the face of the Australian economy free of most of the constraints imposed on just about every other locally incorporated company.”

Peter Thiel, the billionaire libertarian and Trump supporter who was one of Facebook’s first investors, is nothing if not honest about how Silicon Valley views the world and its place in it. According to the man who once funded a defamation case that put an online magazine he didn’t like out of business, “competition is for losers.” •