IN A SENSE, Oscar Manutahi Temaru lost the battle but won the war. Not long before he ended his term as president of French Polynesia this month, he achieved his long-held goal of increasing support for the Maohi people’s right to self-determination. Temaru has been campaigning for independence from France since the 1970s.

In a historic decision, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution on 17 May to reinscribe French Polynesia on the UN list of non-self-governing territories. The resolution, sponsored by Solomon Islands, Nauru and Tuvalu with support from Vanuatu, Samoa and Timor-Leste, was adopted by the 193-member UN General Assembly without a vote. It ends a sixty-five-year period during which French Polynesia has been absent from the list of countries recognised as colonial possessions.

The resolution asks the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation to debate the issue of French Polynesia at its next session and report back to the General Assembly. It also calls on the French government “as the Administering Power concerned, to intensify its dialogue with French Polynesia in order to facilitate rapid progress towards a fair and effective self-determination process, under which the terms and timelines for an act of self-determination will be agreed.”

The right to self-determination does not necessarily equate to political independence. Under UN decolonisation principles, a referendum of the “concerned population” can consider a range of options, including integration with the colonial power, greater autonomy, free association, or full independence and sovereignty.

There’s a long way to go before the people of French Polynesia decide on a new political status. Temaru’s opposite number, the incoming president Gaston Flosse, denounced the “tyranny” of the UN decision. A long-time opponent of independence, Flosse claims a popular mandate for his loyalty to France.

But even as a symbolic measure, the UN resolution sparked fireworks and fury in Paris. After writing to all member states in an unsuccessful bid to delay or scuttle the resolution, France’s UN ambassador boycotted the General Assembly session. “This resolution is a flagrant interference,” said the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “with a complete absence of respect for the democratic choice of French Polynesians and a hijacking of the decolonisation principles established by the United Nations.” The French nationalist party, the National Front, denounced the United Nations, “recalling with great force that the future of the French territories can only be seen within the bosom of the French Republic.”

Since the end of nuclear testing in 1996, France has sought to improve relations with members of the Pacific Islands Forum. But the fierce reaction to the UN resolution suggests that Paris is not planning to relinquish its role as a colonial power in the region any time soon. And the fact that the UN resolution was sponsored by French Polynesia’s island neighbours shows that the debate about colonialism in the region isn’t going to go away.

FRANCE first colonised part of Polynesia as the Etablissements Français de l’Océanie in the mid nineteenth century. By the end of that century, the five eastern-Pacific archipelagos we now call French Polynesia had fallen under French control. Since then, their status has evolved from protectorate to colony, then from “overseas territory” to “overseas country” to today’s “overseas collectivity” of France, each shift in terminology reflecting changes in colonial policy in Paris.

For fifty years after the founding of the United Nations, Paris refused to accept monitoring of decolonisation in the Pacific, arguing that the Pacific territories enjoyed self-government within the French Republic. The newly created United Nations established a list of non-self-governing territories in 1946, calling on administering powers to promote economic, social and ultimately political development in their colonies. But from 1947, France refused to transmit information on its overseas territories to the General Assembly, as required under Article 73 of the UN Charter. A revised UN list of territories in 1963 ignored France’s Pacific dependencies, apart from the joint Anglo-French condominium of the New Hebrides.

After the end of nuclear testing at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in 1996, France began to change its policy in the Pacific region. The signing of the 1998 Noumea Accord – an agreement between the French state and supporters and opponents of independence in New Caledonia – acknowledged the need for decolonisation and improved regional relations. President Jacques Chirac began the devolution of more powers to France’s overseas territories in 2003. New Caledonia and French Polynesia both gained observer status at the Pacific Islands Forum (which links Australia, New Zealand and fourteen independent island nations), and upgraded to associate membership in 2006.

These changes were too little, too late, for the FLNKS independence coalition in New Caledonia and the pro-independence party Tavini Huiraatira in French Polynesia. These nationalist movements have long sought support in their quest for a new political status, and the United Nations is seen as a crucial forum.

The latest UN resolution means that French Polynesia joins sixteen other territories on the UN list of non-self-governing territories, including five in the Pacific region: New Caledonia (under French administration); Tokelau (New Zealand); Pitcairn (United Kingdom); Guam and American Samoa (both United States).

New Caledonia was only reinscribed on the UN list through a UN General Assembly resolution in December 1986, after campaigning by members of the Pacific Islands Forum. The resolution came at the height of armed conflict during 1984–88 between the French armed forces and supporters and opponents of independence. Australia and New Zealand joined their island neighbours to support New Caledonia’s reinscription, fearful of the radicalisation of the Kanak independence movement and perceived Soviet advances in the region.

In French Polynesia, the independence movement has sought the same sort of recognition for decades. As leader of the Polynesian Liberation Front, Temaru first lobbied at the United Nations in 1978. He patiently sought support from Pacific governments throughout the 1980s and 1990s, gaining solidarity from the Pacific Conference of Churches and the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement, but little action came from neighbouring Polynesian nations.

In contrast, the independence movement in New Caledonia gained extensive support from the Melanesian Spearhead Group, which links the FLNKS and the governments of Vanuatu, Fiji, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea.

Since reinscription in 1986, New Caledonia has been scrutinised by the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation every year. The governments of France and New Caledonia even invited the UN committee to hold its regional seminar in Noumea in 2010. Maohi nationalists are angry that the rights extended to New Caledonia under the 1998 Noumea Accord do not extend to other French dependencies in the region. Symbolically, Oscar Temaru was refused entry to the UN’s 2010 decolonisation seminar in New Caledonia’s capital.

GASTON FLOSSE first served as president of French Polynesia in 1984–87 and was re-elected in 1991. The long rule of this fierce opponent of independence came to an end in 2004 after Temaru’s Tavini Huiraatira party united with other groups in the Union for Democracy coalition, or UPLD, and defeated him in closely fought elections for the French Polynesian Assembly. For the first time, French Polynesia had a president who supported independence from France.

Since then, local opinion has shifted slowly but significantly, even as control of the government has swung back and forth between supporters and opponents of independence. (Unstable political coalitions and Paris’s unceasing opposition to Temaru’s agenda have combined to bring about eleven changes of leadership since 2004.)

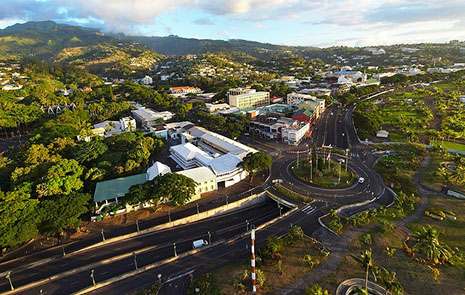

In 2011, the French Polynesian Assembly in the capital, Papeete, narrowly voted for the first time to support Temaru’s call for UN reinscription. A legal challenge to the Assembly vote failed at the Administrative Tribunal of Papeete in early 2012.

The UPLD also looked to Paris as France moved towards presidential elections in May 2012. After years of conservative rule under presidents Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy, the Tavini Huiraatira party had aligned itself with the French Socialist Party. Before his 2012 election as president, François Hollande signed a cooperation agreement with Tavini in his role as Secretary General of the Socialist Party, formally recognising the right to self-determination for the Maohi people.

The UPLD coalition decided to soft-pedal their reinscription push at the United Nations during 2012 in order to avoid embarrassing Hollande in the midst of the presidential elections. Once elected, however, Hollande began to back away from the principles set out in the inter-party accord.

With Australia and France signing a Joint Statement of Strategic Partnership in January 2012, Canberra too has been less than enthusiastic about Temaru’s reinscription initiative. When I interviewed him last year, Australia’s then parliamentary secretary for Pacific Island affairs, Richard Marles, described France as a long-term stable democratic partner in the Pacific and reaffirmed Australian opposition to re-inscription. “We absolutely take our lead from France on this,” he said.

Meeting in Rarotonga in August 2012, Pacific Islands Forum leaders reiterated their support for the principle of self-determination but didn’t endorse the call for re-inscription. Instead, the Forum communique welcomed “the election of a new French government that opened fresh opportunities for a positive dialogue between French Polynesia and France on how best to realise French Polynesia’s right to self-determination.”

A month after the Forum, without the restraining influence of Canberra and Wellington, the leaders of Samoa, Solomon Islands, Fiji and Vanuatu lined up at the UN General Assembly, explicitly calling for action on decolonisation. Vanuatu’s then prime minister, Sato Kilman, called on “the independent and free nations of the world to complete the story of decolonisation and close this chapter.” He urged the United Nations “not to reject the demands for French Polynesia's right to self-determination and progress.”

In the year Samoa celebrated its fiftieth anniversary of independence from New Zealand, prime minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi told the General Assembly, “In the case of French Polynesia, we encourage the metropolitan power and the territory’s leadership together with the support of the United Nations to find an amicable way to exercise the right of the people of the territory to determine their future.”

The same month, with Fiji’s foreign minister Ratu Inoke Kubuabola in attendance, the Sixteenth Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement, in Tehran, issued a new policy on decolonisation. According to its communique, “The Heads of State or Government affirmed the inalienable right of the people of French Polynesia–Maohi Nui to self-determination in accordance with Chapter XI of the Charter of the United Nations and the UN General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV).”

Opinion was also shifting at home. In August 2012, the Eglise Protestante Maohi, the Protestant church that is the largest denomination in French Polynesia, voted for the first time to support Temaru’s call for re-inscription. “The reinscription of Maohi Nui on this list constitutes one way to protect the people from decisions and initiatives of the French State that are contrary to their interests,” said the church executive. “This reinscription would serve, through the recognition of the rights of the Maohi people, as an efficient means of protecting their heritage and allowing them to remind France that she must clean our country of all the nuclear waste that has been left here.”

The following month, the Central Committee of the World Council of Churches added its voice, calling on “France, the United Nations, and the community to support the reinscription of French Polynesia on the UN list of countries to be decolonised, in accordance with the example of New Caledonia.”

WITH increasing regional support, the formal bid for reinscription was relaunched in early 2013, with extensive lobbying in New York by Oscar Temaru and France’s senator for French Polynesia, Richard Ariihau Tuheiava.

In January, Temaru addressed a meeting of the Co-ordinating Bureau of the Non-Aligned Movement in New York, seeking their support. “This is yet another case of David against Goliath, and the reason why we want our country back on the UN’s list of non-self-governing territories,” he said. “Without the UN as a referee between France and us, this is once again an unfair and uphill battle. Don’t get mistaken – this is not a request from us to get independence without our people’s vote. What we seek is a fair evolution of our relations with France, with the oversight of the UN.”

In February, the UN ambassadors for Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Nauru formally lodged a draft resolution at the General Assembly. But in spite of pre-election pledges by President Hollande, French diplomats launched a sharp attack on the initiative. The assault was led by France’s UN ambassador Gérard Araud, a graduate of the prestigious Ecole Nationale d’Administration who had represented France as a diplomat in Washington, NATO and Tel Aviv. Araud lobbied hard to have the resolution delayed in the hope that it would lapse after the May 2013 elections in Papeete.

In the interests of compromise, the sponsoring states issued a revised version of the resolution on 1 March, but France sought for weeks to keep the resolution out of the General Assembly. Although colonial powers including the United States and Britain agreed to back France, other UN member states were astounded by the vigour with which France pressed its case. Denouncing the “violence and condescension” of Araud’s interventions, Temaru wrote to the French president on 27 March, calling on him to bring the ambassador to heel.

“Without wanting to embarrass you with the procedural details or the reasons invoked to refuse us a date,” Temaru wrote, “I would draw to your attention the growing frustration and incomprehension over France’s position, which we have been informed of by several UN member states. For the majority of these states, the right to self-determination is a sacred principle, inscribed in the UN Charter… The French pressure towards the President of the General Assembly is similarly perceived as the denial of the democracy that is at the heart of the General Assembly… If some of your confreres in the P5 [permanent members of the Security Council] seem to be accepting the French action on our dossier, others have shared their astonishment with us.”

French Polynesia’s local elections on 5 May saw the defeat of President Temaru’s UPLD coalition, with voters angry over the government’s management of French Polynesia’s post-GFC fiscal crisis, declining tourism and growing unemployment. The return of Gaston Flosse, an ageing politician currently appealing a series of convictions for corruption and abuse of office, highlights the political stasis in Papeete, and the lack of vision for new post-nuclear economic options.

After his election, Flosse immediately wrote to the president of the General Assembly, Vuk Jeremic of Serbia, in an unsuccessful attempt to delay action on the resolution. France’s ambassador boycotted the session on 17 May and Britain, the United States, Germany and the Netherlands all disassociated themselves from the consensus vote. Fearful of a growing regional debate about West Papua, Indonesia’s representative stressed that the “adoption was solely based on a specific historical context and should not be misinterpreted as precedence by other territories whose cases were pending with the Decolonisation Committee.”

IN THE aftermath of the UN resolution, Gaston Flosse is now seeking to pre-empt a debate about options and timetables for self-determination by calling for an immediate referendum on independence. Buoyed by his success in the Assembly elections, Flosse is hoping that a quick vote would overwhelm the UPLD, which must rally a population fearful that France would abandon them, politically and financially, after independence.

For Temaru and the UPLD, any referendum must be based on UN practice and principles, and the thorny question of voting rights must be resolved. Flosse has argued that all French nationals resident in the territory have the right to vote in a self-determination referendum. Temaru, echoing the process established by the Noumea Accord in New Caledonia, has argued for a restricted electorate limited to indigenous Maohi and long-term residents. Any vote should be preceded, he says, by a lengthy transition, with information in local languages about all options and a timetable for the transfer of authority.

In spite of French anger over the UN resolution, the decolonisation agenda has some way to go. New Caledonia has been on the UN list since 1986 and increased UN scrutiny does little to change the reality on the ground. (Under the Noumea Accord, after elections in 2014 New Caledonia will move towards a decision on its political status, with a possible referendum before 2019.) With limited staff and finances, the UN Special Committee on Decolonisation lacks the capacity to fully support the remaining territories.

Even so, self-determination will remain on the region’s agenda over the coming decade. The Melanesian Spearhead Group meets in June in New Caledonia, with FLNKS leader Victor Tutugoro taking over as chair of the sub-regional body at a crucial time. The UN resolution has buoyed the Kanak independence movement, with the FLNKS Political Bureau warmly welcoming the decision. As Maohi nationalists celebrate their victory, the future of France in the South Pacific is yet to be decided. •