“I cannot live with You —” goes Emily Dickinson’s poem. “It would be Life —/ And Life is over there —/ Behind the Shelf.” Once upon a time many Australian homes had the books of Patrick White out front of their shelves, as did classrooms and libraries too. It’s different today. Like many others, I was shocked to find recently that the University of Adelaide’s Barr Smith Library was giving away books from its Australian literature collection. The trolleys of unwanted books included works by White and a copy of David Marr’s indispensable biography of the author. They had gone straight from the shelves into a culture of forgetting.

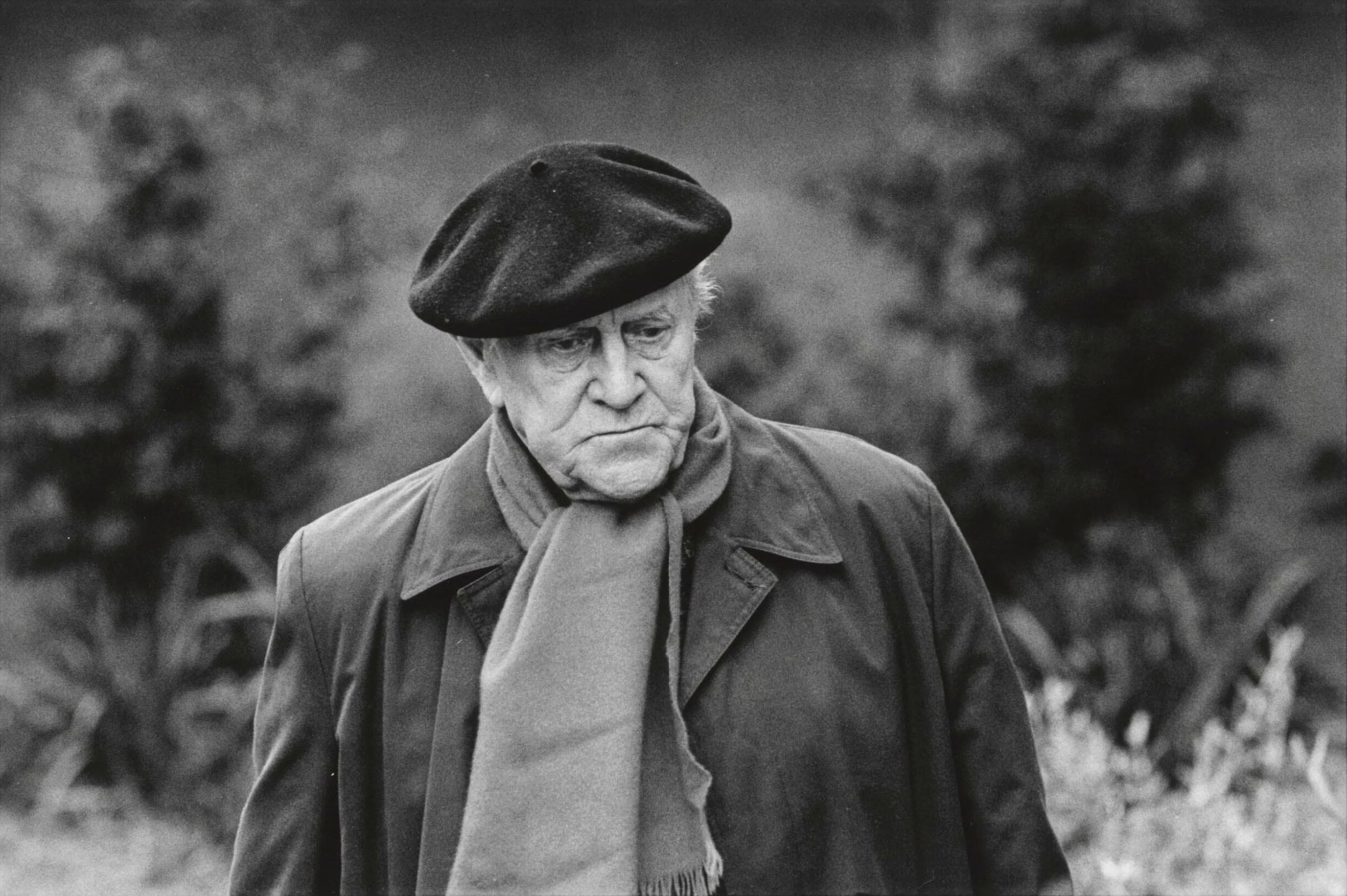

White’s unsmiley face, reproduced in Brett Whiteley’s portrait on the cover of Marr’s book, Brendan Hennessy’s subtle photograph and William Yang’s candid late-life snaps, has become an image of another kind of sadness — neglect. Efforts to save White’s house as a museum on Sydney’s Centennial Park came to nought. Ian Fairweather’s painting “Gethsemane” that hung above his writing desk was de-accessioned in 2010 by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, to which he had gifted it. (Fortunately Philip Bacon purchased the work which now hangs in the Queensland Art Gallery.) The prize for Australian authors that White endowed in his own name is regarded unkindly as a consolation prize. And there was the Wraith Picket hoax back in 2006 in which publishers were exposed by failing to recognise the chunk of The Eye of the Storm a journalist from the Australian submitted under the name of “Wraith Picket” (an anagram). The submission was rejected. Can we not live with Patrick White any longer?

Vrasidas Karalis’s new book, On Patrick White’s Dilemmas, opens up the question again. Inevitably any thinking about White as a problem requires reflection on larger matters — Australia and contemporary culture and politics and all the rest — which soon descends into the “heavy plop-plop of Australian bullshit” that White himself loathed. So please bear with me.

Karalis, professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine studies at the University of Sydney, starts with a funny story. As a schoolboy in Greece he got hold of a Greek translation of The Tree of Man and tried to read it to his grandmother. She was interested in Australia, the promised land for which many had left her village in the 1960s. But the novel made Afstralia sound worse than Greece and was boring too. She refused to go on. Years later Karalis met the hapless translators who had done the job when White won the Nobel prize in 1973 and didn’t want to be reminded of “that dreadful flop.” They had not been able to get into White’s language, his fractured English. That would be left to Karalis, who went on to translate Voss and The Vivisector into Greek after relocating to Sydney as an academic in 1990 and falling in love with White’s work. The good translator is closer to an author’s work than any other reader.

Karalis’s new book is rhapsodic criticism of a rare kind these days. He returns persistently to White’s sentences as the ground for the illumination he finds in the author’s work. He values White’s “vernacular orality” and his “strong sense of vulgarity.” White’s dilemmas for Karalis are part of his being Australian, although it is not primarily as an Australian writer that Karalis reveres him. His book distils a lifetime’s reading, writing and teaching across swathes of world literature.

To make the point Karalis throws out dizzying comparisons: White’s novels “are structured like the Arabian Nights or even Cervantes’s Don Quixote”; they “recapitulate the history of the genre all the way down to Dostoevsky, Proust, Joyce, Mahfouz, Gordimer and Soyinka”; “in White, Beckett meets Groucho Marx — and both fuse in an Elizabethan tragedy”; “we listen to his novels the way we listen to Arnold Schoenberg’s or Igor Stravinsky’s music.”

This personal response is fuelled by Karalis’s rage at what the contemporary academy has become, especially in Australia, especially in the humanities, where what he calls “the cult of presentism has become the dominant method of unimagining the past of literature, restricting everything to a superstitious cult of nowness.” He refers to his own essay as “ranting,” a “diatribe.” He knows he’s “unhinged,” confirming a stereotype of the Greek as “speech-mad.” But he goes on. The result is opinionated, dense, polyglot, wonderfully idiosyncratic, all the better for its passionate energy.

Literary criticism doesn’t have much space to spread its wings in contemporary Australia in an era of disappearing literary magazines and shrinking institutional support. It has gone, over a century, from the occasional insights of sharp-eyed practising writers like Virginia Woolf and D.H. Lawrence, and committed amateurs like Nettie Palmer in Australia, to the industrial-strength professionalism of the postwar academy, from which literary research has largely devolved into such measurable applied activity as data analysis, compilation and the like that may generate grant funding.

Literary biography has become an accessible proxy for literary criticism, interestingly so in Australia where recently living authors can be celebrated by those who remember them. Personal recollections draw on the presence of writers among us as fellow citizens, walking the same streets, being seen at festivals, in ways that were not possible for previous generations who read authors who were mostly out of the country.

Brigitta Olubas’s acclaimed biography of Shirley Hazzard in 2023 was followed by two biographies of Frank Moorhouse in the same year and two biographies of Elizabeth Harrower this year. Karalis’s book on White fits the trend. It’s a memoir of himself as a reader of White, although they never met. Karalis did meet White’s partner, the subject of a previous book, Recollections of Mr Manoly Lascaris, published by Brandl & Schlesinger in 2014. They disagreed about Greekness.

Karalis reads White as an exception, a singular all-time great whose dilemmas are those of humanity, intimately, uncompromisingly shared with readers through extraordinary language and imagination. “You are the only historian of human emotions in this colonial outpost — and remain so to this day,” Karalis writes in a postscript addressed to White. He appreciates the “continuous unfolding” of White’s work, “a writing of dilemmas and abeyances, not of answers and statements,” where “diffuse emptiness denotes the hidden elements of numinosity and unworldliness that emerge, now and then,” and only as “actualised… by synergistic readers,” “something which [White’s] very language struggles to envelop and inhabit, but which is constantly deferred and displaced.” White’s dilemmas, of being an outsider to the society of which he is also an insider, are writ large in a struggle of body and soul and contending versions of the real.

The sense of “perpetual becoming” across White’s work leads Karalis to value highly The Vivisector (1970), White’s portrait-of-the artist novel that shows the writer keeping pace with a changing Australia. This connects to a point made powerfully by Christos Tsiolkas in his 2018 essay on Patrick White for Black Inc.’s Writers on Writers series. “I believe one of White’s achievements is to link the pioneer experience of White Australia to the general history of migration to this country,” Tsiolkas writes. “The move from “homelessness” and estrangement to “settlement” and the coming to terms with exile… is now one of the key shared experiences of people across the globe,” he adds: “every narrative of exile and migration is founded on the creation of oneself anew in a ‘new world.’” Its expression demands a continuous creative reimagining of realism and of myth from the writer.

Both Tsiolkas and Karalis credit Mr Lascaris for the “imaginative empathy” with which White writes of exile and of the mystical home that Greek orthodoxy (however unorthodox) might offer. What White writes “seems real and present to us,” Tsiolkas says. “His is an Australian English.”

Black Inc.’s Writers on Writers series introduced memoir into literary commentary by encouraging writers to explore the personal nature of their literary affinities. Tsiolkas tells us how he left a bunch of wildflowers as a thankyou in the letterbox outside the house where White and Lascaris lived. Ceridwen Dovey’s Writers on Writers essay on J.M. Coetzee begins from the remarkable image of her mother, a Coetzee scholar, reading Coetzee’s novel Waiting for the Barbarians as she breastfed Dovey at night in South Africa in 1980. “I’m still marked by that embodied encounter with his writing,” Dovey says.

The latest addition to that series is Geordie Williamson’s welcome essay on Alexis Wright. He saves for the end a postscript that confesses his forebears’ complicity in the mercantile ravaging of First Nations peoples in colonial times through a “proto-multinational” that had devastating effects particularly on Rapa Nui (Easter Island): “the same displacement, forced assimilation, economic immiseration and so on. It could have as easily been the Gulf Country as the Eastern Pacific.” Wright’s fiction speaks to Williamson personally about “issues affecting not just the author’s community but us all… For we are all embodied.” Her work “imagines an alternative. It depicts groups for whom citizenship is inextricably linked to stewardship of place, not a licence to exploit.”

Earlier in the essay Williamson focuses on the iconic opening of White’s The Tree of Man, where a man cuts down a tree to clear the land: “the first time anything like this had happened in that part of the Bush.” Williamson interprets the scene from a contemporary vantage-point: “the first of a series of desecrations that will see this stand of gums overwritten by the suburban sprawl of an Australian city.”

“White writes on the other side of the catastrophe he prophesies… But he could not know the pain of colonisation from the inside, not directly,” observes Williamson, whereas Alexis Wright, from her first novel, is feeling her way “to communicating this terrible, magnificent, perspective.” Her characters “exceed the bounds of a reality imposed on them,” Williamson explains. “Elements of ancestral myth bleed into the town’s contemporary reality, just as obligations to old lore bump up against the necessity of self-determination.” He calls it “Indigenous realism” — for this is what happened and is happening: “the terrible rupture… suffered by First Nations people since European arrival: the loss of language, lore and connection to country.”

When White won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973 the citation commended him for introducing “a new continent into literature.” The phrase makes us uncomfortable today, suggesting a literary terra nullius where there was nothing previously, ignorant of the rich oral literature created and performed in Australia for centuries before the English language arrived. Already in 1964 in The World of the First Australians, Ronald and Catherine Berndt were drawing attention to an Aboriginal “tradition of oral story-telling… dramatic art… arranged as sagas, of Odyssean quality.” It is an old continent in literature too.

David Marr remarked at a double anniversary celebration in Adelaide in 2023 to mark the award of the Nobel Prize to White in 1973 and to Coetzee in 2003 that earlier Australian writers might not have agreed that it was a new continent either. Christina Stead was writing Australia into literature in For Love Alone, published in 1945 (“Oh, Australian, have you just come from the harbour?”) and Henry Handel Richardson was a contender for the Nobel Prize in the 1930s with the success of her Australian epic, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, and Nettie Palmer’s advocacy. White had Swedish supporters but had to wait for Beckett, Solzhenitsyn, Heinrich Böll and Neruda to win before him. He came in ahead of Saul Bellow and Nadine Gordimer, though, as Barnaby Smith relates. Böll and his wife Annemarie had produced an admired German translation of The Tree of Man in 1957, which might have helped.

At the anniversary celebration Marr reported on the modest sales of White’s work today. But is he really unread or are his readers just not vocal, an invisible grassroots community behind the shelf — where the Life is? Jane Grant, who runs St Arnaud Books, specialising in secondhand Australian literature, says White is a steady seller. All sorts of people come into the shop and take the novels home. Some of the sharpest creatives and scholars around are engaging with White. Brink Productions’s brilliant adaptation of White’s short story “Down on the Dump” for actors and string quartet shows what is being done. Samuel J. Cox won the Association for the Study of Australian Literature’s A.D. Hope Prize in 2022 for his essay on Voss, “I’ll Show You Love in a Handful of Dust.”

At the annual Australian Studies in China conference, held in Shanghai in October, Li Yao, the senior translator of Australian literature into Chinese, gave me a copy of his translation of White’s The Twyborn Affair. He said it was the most difficult book he had ever worked on, his project during Beijing’s rigorous COVID lockdown. White has been served well by his Chinese translators — Hu Wenzhong, Zhu Jiongqiang and now Li Yao. China’s Twyborn Affair has been released by a top publisher, described as an astonishing 1970s classic translated into Chinese for the first time. Papers on White’s work used to dominate the annual Australian Studies Conferences in China. Not so much now, but he hasn’t disappeared altogether.

To end with my penny’s worth of Patrick White memoir. White’s plays were a talking point in Adelaide in the early 1960s, rejected by the Adelaide Festival grandees, applauded by his supporters. There was a frisson when the writer came to town.

I was too young a schoolboy to see those plays but I did try to read Riders in the Chariot. I didn’t understand it, though Miss Hare stayed with me. My parents gave me The Vivisector for my eighteenth birthday. It filled a summer. I met White only once, in a queue at the Bank of New South Wales branch in London that Australian travellers used. He had been to Covent Garden the night before to see Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni. The stage trapdoor had opened prematurely and Donna Anna fell into it, inadvertently experiencing the descent into hell that was meant for her seducer at the end. White described the soprano as “puddingy.”

I still have that copy of The Vivisector on my shelf. “From Mum and Dad, 9.11.70.” Maybe it’s time to read it again. •

On Patrick White’s Dilemmas: A Personal Essay

By Vrasidas Karalis | Brandl & Schlesinger | $26.99 | 224 pages