With smartphones to hand, the line between the audience and the media is in a constant state of flux. And in a world saturated with digital images, it’s the grisly, disturbing and explicit that often get the most clicks. Debates rage about whether some graphic material shot by amateurs — sometimes as souvenirs — should ever be shown, with a term like “poverty porn” equating images of extreme suffering with the exploitation that goes on in the sex industry. But could it simply be that we don’t want to be discomforted?

Elizabeth Gertsakis’s exhibition Outrage, Obscenity and Madness (currently showing at the Geelong Gallery) and Sarah Sentilles’s book Draw Your Weapons offer new ways to consider how the values of our times shape our responses to troubling content. Both the book and the exhibition offer some coordinates for plotting our responses to the deluge of troubling images.

Elizabeth Gertsakis’s digital paintings and works on paper reinterpret the illustrations accompanying reports of crimes and misdemeanours published in newspapers edited by Richard Egan Lee in Victoria the 1870s. Her exhibition and accompanying essay examine and revive the visual punch of images that populated newspapers with names like Police News, Citizen Press and Banner of Truth.

“A Farmer’s Daughter Saved from Outrage by a Brave Dog,” from Outrage, Obscenity and Madness.

Gertsakis discovered this body of awkward and brutish images during a fellowship at the State Library of Victoria. Partially motivated by concerns about censorship, she set out to understand what made Egan Lee’s images so unsettling and compelling. Exhibiting little skill and refinement, the prints crudely depicted current events. As Gertsakis told me:

I was moved by this material which was drawn, combined, collaged, patched together and then given a dramatic, often volcanic and confronting sense of the violence or tragedy of the initial event. It made me think in more emotional ways about the suffering of the poor and the unlucky and vulnerable at a time when there was no support other than highly limited “Christian Charity.”

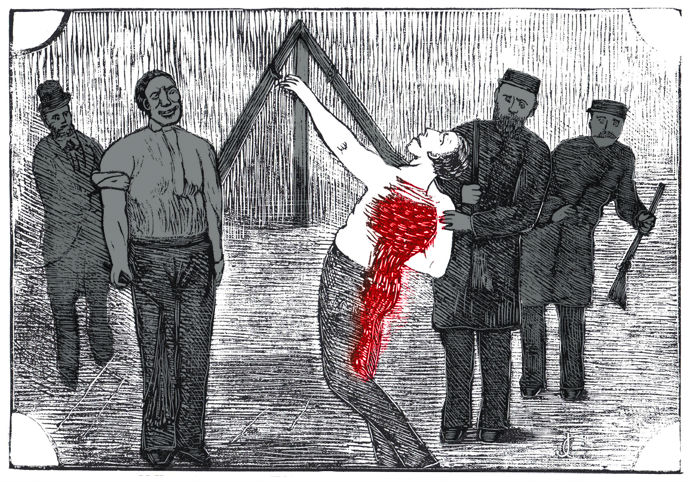

Egan Lee, obsessed with crime and calamity, was also a reformer who wanted his stories to draw attention to the plight of women and children in order to improve their circumstances. The established media, polite society and the law did not take kindly to what they regarded as the shocking imagery that accompanied his stories, and Egan Lee found himself the subject of multiple slander and obscenity cases. Each time he was found guilty, he was jailed and his paper shut down, but on release the resilient editor would simply start up under another masthead. Egan Lee was finally silenced when the media barons of the time convinced parliament to amend Victoria’s censorships laws so that distributors and publishers, as well as editors, could be sued for obscenity. These censorship laws remain in place today.

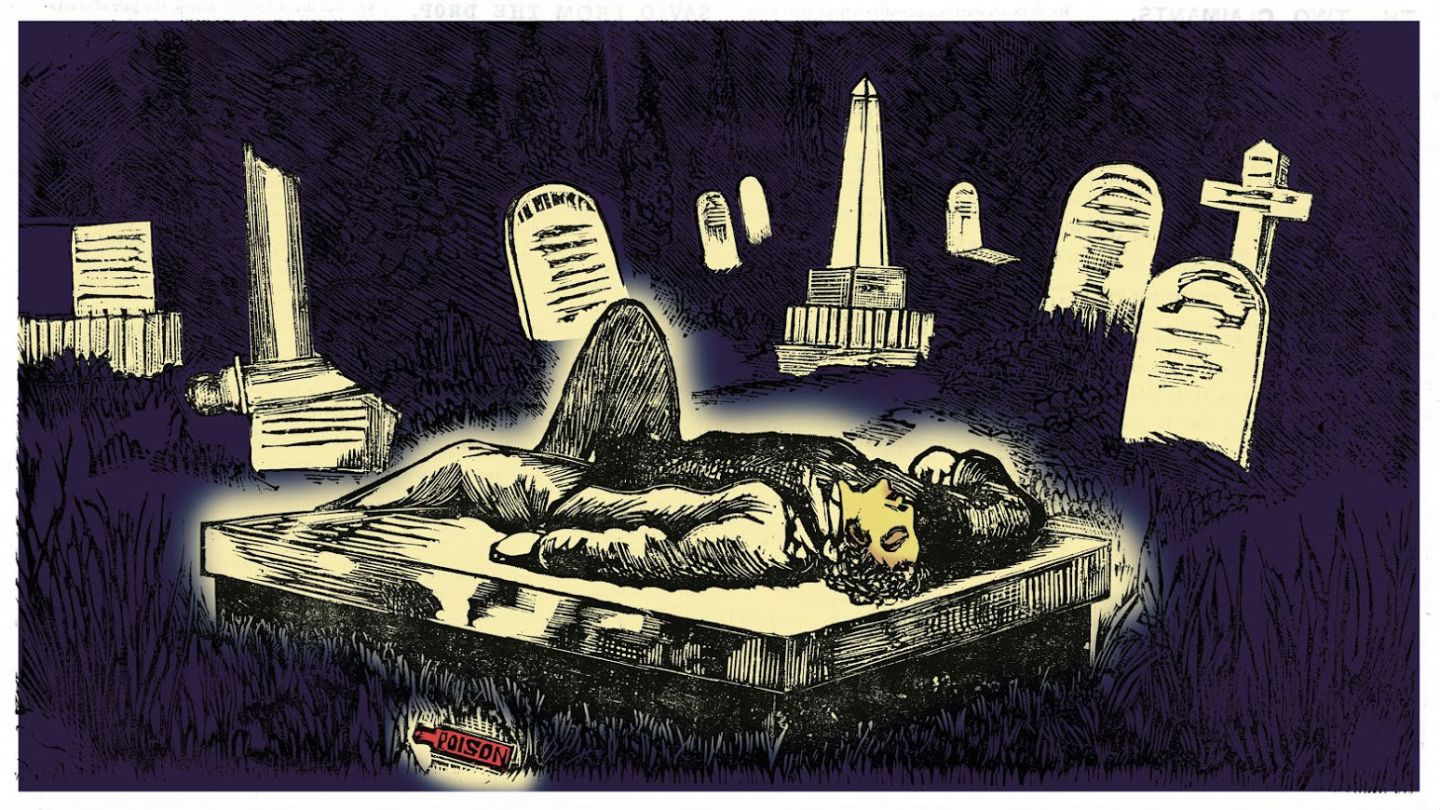

“Melancholy Suicide in Geelong Cemetary – Verdict of a ‘Christian’ Jury,” from Outrage, Obscenity and Madness.

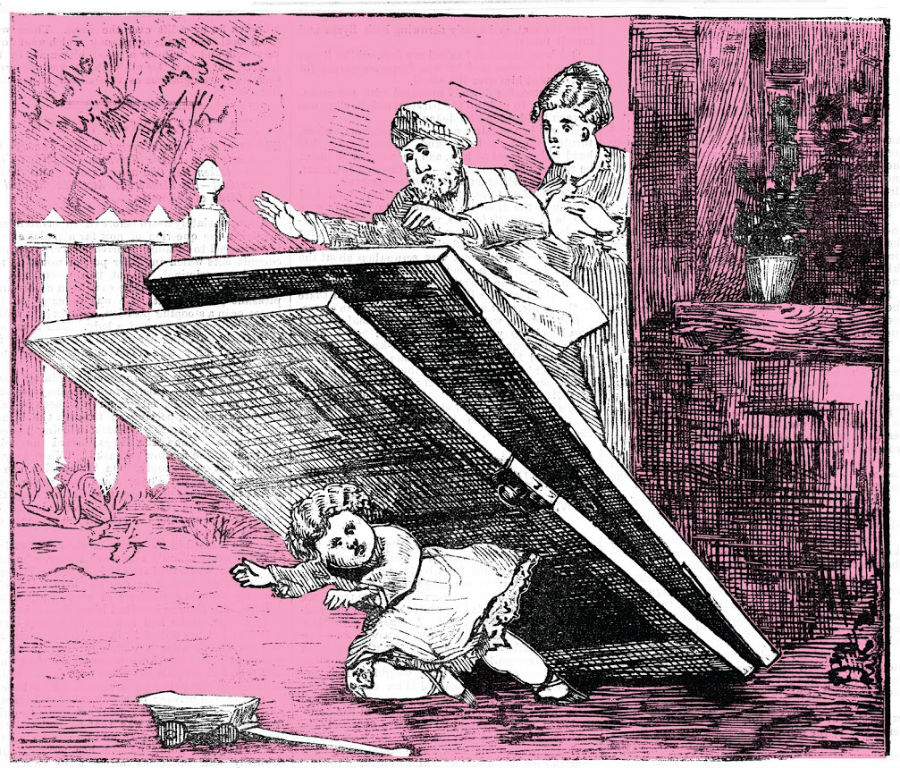

The original illustrations confronted pictorial and social aesthetics of the time and ran alongside Egan Lee’s tabloid stories about rape, abortion and the scandalous behaviours of politicians. In an early precursor to citizen journalism — though more a response to budgetary constraints than a democratic gesture — Egan Lee invited members of the public to submit their drawings of news stories. Arriving at the newspaper as amateur line drawings, they were worked on by Egan’s “combiner,” who removed some of the irregularities in the originals by copying, collaging and borrowing from the techniques of the master printmakers of history. Such was the pull of these images that Lee’s publications sometimes outsold the Age. Was it the awful content of the stories or the impact of the grotesque imagery that drew such an enthusiastic audience? Perhaps their technical deficiencies were part of their dramatic and authentic power?

In the same way, unpolished amateur photography often activates today’s debates about atrocities and suffering. The unadorned brutality of the Abu Ghraib torture images was the catalyst for Sarah Sentilles’s Draw Your Weapons, which recounts the author’s engagement with two men. One was a young student called Miles who served in the US military as a guard at Abu Ghraib; the other, Howard Scott, suffering from the onset of dementia, had been a conscientious objector during the second world war. The catalyst for each relationship was photographic imagery. There were the snaps by the soldiers who humiliated and tortured the Abu Ghraib prisoners, which caused Sentilles to abandon her studies to be a priest and eventually led to a discussion with students in the class Miles attends. And there was a photo of Scott being presented with a violin on his eighty-seventh birthday — a violin he had started making while imprisoned for refusing to serve in the US military.

“Fatal Accident to a Child, During the Late Gales,” from Outrage, Obscenity and Madness.

Sentilles combines fragments of narrative, memoir and journalism to plot a peripatetic path through contemporary debates about war and suffering. She considers whether it is possible for art- and image-making to re-engage viewers who feel overwhelmed or apathetic, while restoring dignity to those affected by conflict. In a book with no images, Sentilles interrogates many photographic works that depict violence and suffering, to grapple with the question: do we look or look away?

Sentilles’s description of artist Josh Azzarella’s doctored images of Abu Ghraib provides a way out of the cycle of yes, no, yes. In these reinterpretations, the spaces that held the hooded man, the men on leashes, the line of naked men are now empty. The victims are absent. The people who were the subject of our gaze have vanished and their erasure enables us to avoid participating in their indignity and suffering. Only the grinning perpetrators with their thumbs-up signals remain. But our engagement with the event is not necessarily changed.

Photographer and writer Teju Cole amplified this concern in a conversation with Sarah Sentilles at Adelaide Writers’ Week last month. The most troubling photos of all, he said, are the ones that never emerge. The images we don’t see are obscured by the ones we do. Absence, as much as presence, is the problem.

“Trevarrow, After His Second Flogging, on Pentridge Green,” from Outrage, Obscenity and Madness.

Sentilles argues that the suffering doesn’t go away just because we don’t look. The really important question is not whether we look, but what we do with what we see. What is our responsibility when confronted? She builds on Susan Sontag’s seminal arguments in On Photography to argue that empathy is insufficient. She urges us to ask ourselves what the wishes of the person who is being viewed would be. She anticipates that they would want us to see so that we will then do something — and that something would be political action of some kind that works to restore the dignity of the subject.

Media images generated by amateurs were the catalysts for these two different but parallel enquiries into the power of the image — one contemporary, the other historical. Each of them provides pertinent insights into societal values and responses to violent and disturbing images. Each illustrates how creative works can prompt a re-engagement with injustice and suffering. Both suggest that art can breach indifference and provide a conduit to a new understanding that ends in action.

The Melbourne Establishment in the 1870s thought they could erase the stories of suffering by jailing the image-maker. This suggests we should hold our fire before condemning a publication as gratuitous for showing us something we don’t want to see — and then redirect our indignation into an action that may help restore the victim’s dignity. ●