As he passed his 200th day in office, the height of summer in Washington was coinciding with a political high for Joe Biden. And at the top of his list of achievements were significant legislative advances — some with bipartisan support — for the Build Back Better plan he took to the election.

Back in March Biden signed into law the US$1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, and since then approximately 171 million payments of up to US$1400 per person have gone out to households. Democrats touted the plan as a godsend for the middle class, but perhaps its greatest achievement will be to lift more than five million children out of poverty this year. Although the bill passed without a single Republican vote, many Republican lawmakers have proclaimed its benefits to their constituents.

Biden’s sweeping plans for infrastructure, jobs and families go well beyond tackling the impact of the pandemic. In size and ambition, his US$4 trillion in domestic policy commitments rivals Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs in the 1960s and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s.

In a move that was both astute and characteristic, he chose to split the key legislation into two parts for congressional action. With infrastructure and jobs first up, the White House and congressional Democrat leaders took a gamble that they could get Republican votes. It took months of negotiations, but the US$1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed the Senate last Wednesday with nineteen Republican votes, including the vote of Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, who has declared stopping the Biden agenda to be his priority.

The bill will fund the largest upgrade of roads, bridges, transport systems, ports, power generation and broadband in decades. Fully US$550 billion — mostly from unspent coronavirus relief funding and tighter monitoring of gains by cryptocurrency investors — will fund new investments, including electric car charging stations, zero-emission school buses, better water infrastructure and environmental remediation.

With the passing of that bill, Biden has achieved something that eluded both of his Democrat predecessors, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama: winning sizeable bipartisan support for a top legislative priority. And he did it despite noisy opposition and threats from former president Donald Trump.

Why Biden’s gamble paid off better than anyone could have predicted can be explained by several factors. He used a centrist coalition of senators to lead the negotiations. He did the hard work needed to get the deal over the line, including making significant concessions. (The Senate bill is about US$1 trillion less than that initially proposed.) And he recognised how difficult it would be for Republicans to explain to their constituents why they had refused to support funding to improve the obvious failings of the nation’s infrastructure.

“Today, we proved that democracy can still work,” he proclaimed after the Senate passed the bill. It was a vindication of his election commitment to work with lawmakers across the political aisle.

That was never going to happen with the more expensive remainder of his 2021 legislative agenda. Even getting the more moderate Democrats to support a US$3.5 trillion expansion of federal safety net programs — paid for by winding back Trump-era tax cuts for corporations and wealthy families — will be challenge enough.

But Biden’s wins continued all the same. Just before leaving for the summer recess, the Senate passed a budget resolution that will provide the blueprint for legislation to implement this agenda. The vote was 50–49, the narrowest of margins, but the vital fact is that Biden didn’t lose a single Democrat senator.

Important as they are, these victories are only stepping stones towards enacting the Building Back Better plan. The path will quickly become harder, rockier and dramatically more partisan when Congress returns for the autumn session, when the House must pass its versions of the infrastructure bill and the budget resolution, to be agreed with the Senate in conference. Only then can the infrastructure bill be signed into law and work begin on translating the budget resolution into legislative language that must be passed by the House and the Senate. This package will be brought forward as a budget reconciliation bill, avoiding the Senate filibuster and requiring only a simple majority vote to pass.

The arcane legislative processes are further complicated by the Byrd rule, which limits what can be considered in a reconciliation package, and looming disagreements among House Democrats over the order in which the bills will be considered.

House leader Nancy Pelosi has said that the House will take up the budget resolution as soon as it returns on 23 August but won’t deal with the infrastructure bill until the Senate has passed the reconciliation bill. She is intent on ensuring the Senate includes all the major programs in this bill and is tying the two packages together to keep her whole caucus on board, as moderates grow wary of additional spending and progressives look for more.

The budget reconciliation bill will include a range of measures that will divide Democrats and Republicans on the basis of ideology, not least because of the significant roles (revived if not new) it gives the federal government. Its investments in families, education, healthcare, climate change and immigration include universal preschool for three- to four-year-olds; two free years of community college; the addition of dental, vision and hearing benefits to Medicare coverage; lower prices for prescription drugs; a new Civilian Climate Corps along with many of the climate provisions that didn’t make it into the infrastructure bill; historic levels of investment in affordable housing; and permanent residency for millions of immigrants.

The Republicans have no interest in supporting measures they have derided as “radical Democrat tax-and-spend.” McConnell and House minority leader Kevin McCarthy have been divided on many issues — including the infrastructure bill — but are united in opposing the budget reconciliation proposals.

Daunting as the task might seem, Biden has reason to believe the wind is at his back. Above all, these measures are very popular among voters. Sixty-five per cent of respondents to a recent Quinnipiac poll supported the bipartisan infrastructure proposal, and 62 per cent are in favour of the Democrats’ reconciliation plan. These levels of support are echoed in other polls, even including a Fox News poll.

The reason is simple. Most Americans see Biden’s policies as benefiting the rich, poor and middle class alike, so he is avoiding the divisions that Trump traded on. Employment is up, unemployment is down, and hourly rates in low-wage industries are finally starting to climb.

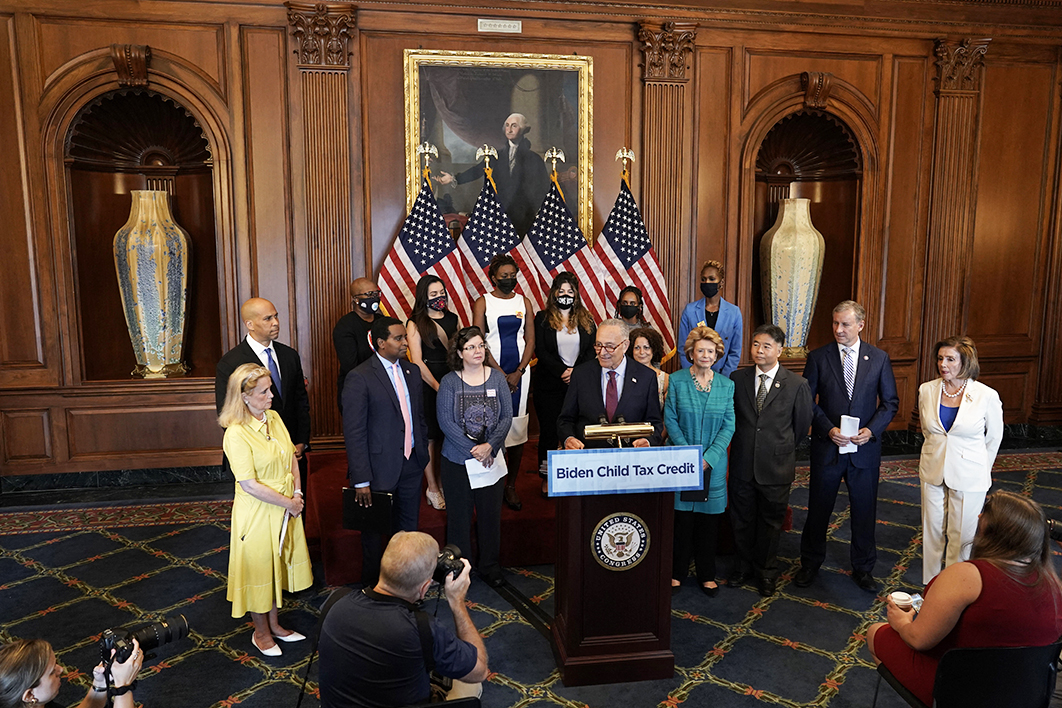

Biden can also rely on the expertise of Pelosi, Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer and his own White House aides to wrangle and cajole congressional Democrats, and juggle their concerns and needs against those of the president.

At the same time, though, other urgent and contentious issues are looming. Unless legislation to fund public agencies is enacted in a timely fashion, a government shutdown is on the cards after the end of the government’s financial year on 30 September. The federal debt limit, already extended by extraordinary measures, must be extended by November.

Important constituencies are eager to see action on voting rights, gun control and social justice reforms. And the pandemic is far from beaten. The partisan divide on issues like masks and social isolation, combined with the conspiracy theories, misinformation and hesitancy, means this is now a pandemic of the unvaccinated. The momentum of the vaccinations has slowed and the Biden administration is struggling to revive it in the states and counties where resistance is high.

Biden’s approval ratings have taken a small hit as a result, although his handling of the pandemic still attracts 55 per cent approval. The most recent Reuters/Ipsos poll found 51 per cent of those surveyed approved of his overall performance and 45 per cent disapproved. (At the same point in his presidency, Trump’s approval rating was 37 per cent.) The same polling found that public health was the key issue for both Democrats and Republicans, ahead of the economy, the environment, healthcare and immigration.

Biden knows his window of opportunity is closing. What doesn’t get legislated by Christmas won’t get done once next year’s midterm elections are looming — a key argument that should work to keep congressional Democrats aligned on the votes ahead. The enactment of these two legislative packages is imperative both for the perceived success of Biden’s first term and for Democrats to have any chance of overturning precedent and keeping their (already razor-thin) majorities in the House and the Senate.

The elephant lurking in the room is Trump. He has a war chest and is intervening in Republican primaries, determined to punish enemies, keep his agenda at the centre of the party and keep himself in the media spotlight. Some fear that the 2022 elections, at least in part, will be a referendum on Trump rather than Biden, particularly if Trump makes them a form of revenge for his 2020 loss.

Biden’s response is to reach out to disaffected Republicans and independents, and his legislative efforts are helping to garner their support. The early success of his infrastructure deal has helped loosen Trump’s grip on Republicans’ decision-making, vindicated the president’s faith in bipartisanship, and affirmed the rationale for his presidency. As he said following Senate passage of his infrastructure bill, “This is what I call governing.” •