Just a few days before Christmas 2023 the federal government announced a tough new vehicle efficiency standard for motor vehicles. The standard — which would belatedly have brought Australia into line with most other advanced economies — encountered predictable opposition from Peter Dutton and his Coalition colleagues and from affected lobby groups, most of it focused on the costs for the car industry and purchasers of new vehicles.

Although the climate impact of motor vehicles did figure in the debate, the direct health benefits of the government’s initial plan were almost entirely absent. Yet an accompanying statement from the government’s Office of Impact Analysis put it, vehicle emissions make a major contribution to the air pollution that can cause “reduced lung function, ischemic heart disease, stroke, respiratory illness and cancer.” Australia’s current regulations, it added, allow “a higher level of noxious and carbon emissions” than in comparable countries.

Lacking strong support for change, the government scaled back and delayed the new standard. But its near-silence on the health impacts and healthcare costs of air pollution raise an important question: was this dimension of the policy fully explored during its development?

More than a quarter of the 2700 submissions received during consultations on the standard came from health, environment and social groups. The potential health benefits of the proposal were virtually ignored in the consultation report, though, beyond a statement that the government’s preferred option would deliver $5.52 billion in health savings over the period 2025–50.

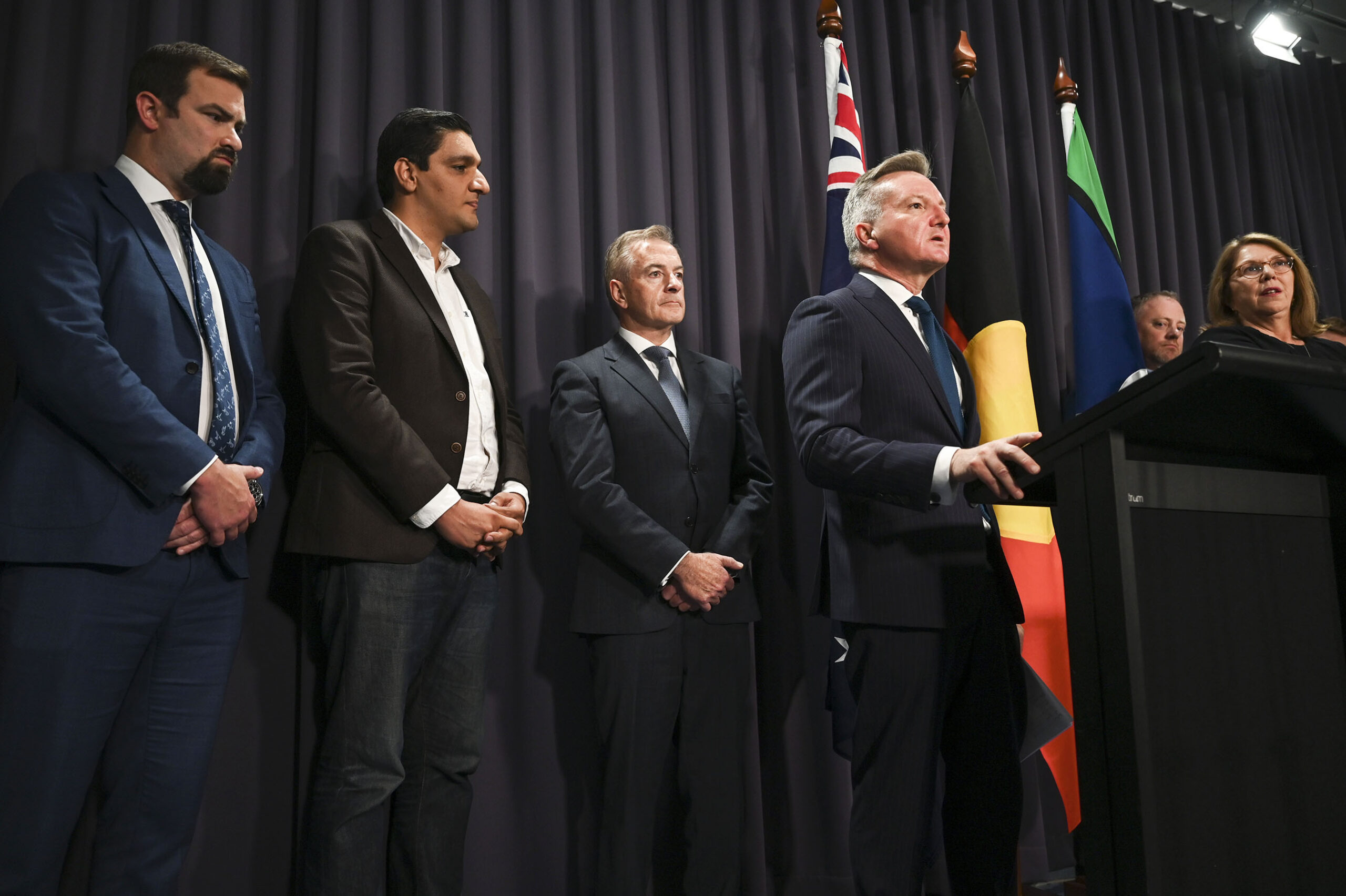

When ministers Chris Bowen and Catherine King announced the watered-down standards late last month, not a health expert was to be seen. Fronting the media were representatives of automobile manufacturers and vehicle traders, one of whom, Tesla’s Sam McLean, welcomed the government’s backdown as a “compromise between all the folks you see up here on stage.”

The health effects of traffic pollution have been recognised for decades. But recent evidence shows them to be far more serious than previously known, causing premature deaths, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, childhood asthma, adverse birth outcomes, diabetes and even dementia.

Yet there’s a shocking dearth of Australian-specific research on these effects. I was able to find only a handful of studies, the results of which vary widely because they use different mechanisms of analysis. The absence of robust data makes it much harder for governments to resist heavy lobbying by industry groups and businesses. Nevertheless, the studies that do exist highlight the imperative for action.

A 2005 study from the Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics found that motor vehicle-related air pollution accounted for between 900 and 2000 early deaths in 2000. The economic costs were assessed as between $0.4 billion and $1.2 billion for morbidity and between $1.1 billion and $2.6 billion for mortality, with most of the burden born by the elderly and the very young living in capital cities.

In 2018 the Australian Burden of Disease Study found that 3236 deaths were attributable to air pollution from particulate matter. Most of these deaths were from cardiovascular disease, stroke, respiratory diseases, lung cancer and type-2 diabetes.

A recent paper from Centre for Safe Air conservatively estimated the annual deaths from air pollution to exceed 3200, with a cost greater than $6.2 billion from years of life lost and an acknowledgement of other, more extensive, health and social impacts.

A paper published in January 2024 using data from 2018 indicated that transport emissions caused between 1000 and 2550 premature deaths and roughly 26,700 cardiovascular hospitalisations, asthma attacks and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease episodes in that year, at a total cost of $910 million.

But arguably the most up-to-date and definitive analysis is an expert position statement on the health impact of traffic emissions from the University of Melbourne, endorsed by the Australian Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance. It finds an annual toll of 11,105 premature deaths, 12,210 hospitalisations for cardiovascular disease, 6840 hospitalisations for respiratory disease, and 66,000 cases of asthma in children aged up to eighteen.

Much of the sizeable variation in these studies reflects the fact that they are measuring contributors to air pollution differently — in some cases by including more than just traffic pollution, in other cases by factoring in different-sized particulate matter (it’s usually PM2.5, the smallest, or PM10) or by including or excluding the effects of nitrogen oxide compounds.

The University of Melbourne paper cites a New Zealand study that took in both PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide. It found that in 2016 some 3300 premature deaths could be traced to air pollution, with more than two-thirds of them attributable to motor vehicles. Air pollution contributed to more than 13,100 hospital admissions for respiratory and cardiac illnesses, including 845 asthma hospitalisations for children and approximately 1.745 million days on which people were prevented from doing the things they might have done if air pollution had not been present. The cost to the New Zealand economy in that year was estimated at NZ$15.5 billion. (The population of New Zealand in 2016 was 4.7 million.)

In Australia, as elsewhere, the burden of motor vehicle emissions falls disproportionately on people who live in urban areas or belong to certain population groups. Unborn and young children, the elderly, ethnic minorities, and those with underlying chronic disease conditions are most vulnerable.

And — as is so often the case — the greatest impact is on those who are most disadvantaged, who are more likely to live in air pollution hotspots and who are already dealing with inequalities in health and access to healthcare. Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare shows that the total disease burden attributable to air pollution is 2.2 times greater in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic group than among the most advantaged.

Recent findings highlight one further reason why air pollution should be treated as an urgent public health issue. Researchers have identified it as one of the three main modifiable risk factors — along with alcohol and diabetes — for Alzheimer’s Disease. People with higher exposure to traffic-related air pollution have been found to be more likely to have the elevated amyloid plaques in their brains associated with Alzheimer’s.

The fine particulate matter, PM2.5, in air pollution is hypothesised to cause inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, contributing to pathology changes. A University of Michigan study that examined the links between different types of PM2.5 air pollution and dementia found that higher exposure to PM2.5 particles from agriculture, road traffic, coal burning, industry and wildfires was linked to an increased risk of dementia.

These studies are observational in nature, but given that fewer than 1 per cent of Alzheimer’s cases are inherited, environment and lifestyle are likely to play a key role in the development of the disease. Moreover, the adverse health effects of air pollution from road traffic should be seen in conjunction with the impact of bushfire smoke, which is an increasingly common threat in Australia.

One more finding should serve to keep the focus on policy rather than politics: there is growing evidence that pollution makes it easier for Covid-19 to spread through the air. An international study has reported that long-term exposure to nitrogen oxide compounds and particulates could have contributed to up to 15 per cent of Covid-related deaths internationally, and up to 3 per cent of deaths in Australia.

In other words, the federal government’s decision to pull back on the new standard was clearly not based on all the available evidence. The loudest voices got the most attention. For whatever reason, Labor also appears to have been influenced by the Biden administration’s concurrent decision to ignore health impacts and cave in to business objections to new air pollution standards developed by the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Even though he is keen to reverse Donald Trump’s rollback of regulations, Biden is obviously looking to ensure he doesn’t face headwinds from powerful business sectors, transport unions and the governors of Republican states in a tough election year. And — importantly — the revised standards he announced this week still place the United States well ahead of Australia.

In polling last month by Resolve Political Monitor, only 22 per cent of respondents supported the vehicle emissions plan in its original form and a whopping 78 per cent either opposed the plan or were unsure. That’s not surprising, especially given that only 38 per cent of voters were aware of the plan. But it also shows that the government didn’t communicate the full benefits of a tougher standard.

Support for new policies — even those that increase fuel efficiency, make electric vehicles more affordable, and improve public health — won’t come if voters don’t know how they will benefit. And when a government fails to communicate effectively it’s no surprise if everything voters know about a proposal comes from the interest groups that oppose it. •