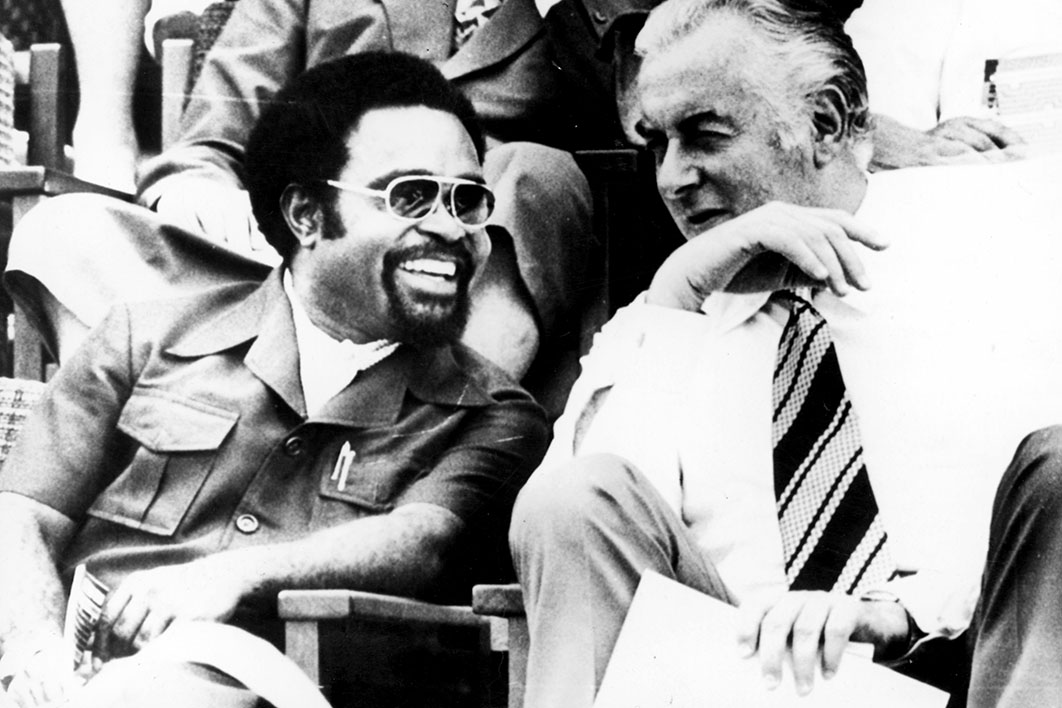

During a visit to Papua New Guinea in 1969, Gough Whitlam was confronted by a brash young politician who stared into the face of the Australian opposition leader and demanded: “So when is Australia going to give us our independence?” Whitlam shot straight back: “How about tomorrow?”

In recounting the story, the feisty and garrulous Michael Somare would concede that for once he was lost for words. But the encounter helped cement a friendship between the two men who would soon transform the histories of both their nations.

Shortly after his PNG visit, Whitlam narrowly lost the October 1969 federal election, despite a 7 per cent swing that saw Labor take sixteen seats from the Coalition. Had he won, PNG would likely have achieved independence if not by tomorrow then at least well before it did in 1975 — an event that white conservatives on both sides of the Torres Strait still decried as a perilous dereliction of Australia’s duty to its primitive colonial territory.

There certainly was some merit in the argument that PNG was ill-prepared to stand on its own feet. The expatriate planters, business figures and bureaucrats who ruled the roost in Port Moresby and in the rich highlands and islands had been in no hurry to surrender their cosy sinecures, and the first Papua New Guineans, including Somare, hadn’t been elected to the National Assembly until 1968. The vast majority of the population still lived in traditional villages, and the country’s infrastructure and institutions were rudimentary.

But both Whitlam and Somare were determined to crash through. After Whitlam’s election as prime minister in 1972, normalising diplomatic relations with China and seeing PNG take charge of its own future were foreign policy priorities. Self-government came in 1973, with Somare installed as chief minister, and full independence two years later.

At a dinner in a house overlooking Port Moresby’s Fairfax Harbour on 16 September 1975, just hours after they had together watched the lowering of the Australian flag and the raising of PNG’s striking new ensign, Whitlam wept as Somare, speaking passionately without notes, extolled his counterpart’s role in delivering independence.

But as much as Whitlam had enabled what the Coalition’s external territories minister Charles Barnes had argued should not happen until the end of the twentieth century, it was the irrepressible Somare, and the exceptional group of young Papua New Guineans who coalesced around him, who made it happen. His death closes the circle on a remarkable episode in peaceful decolonisation.

Somare’s transformation from village teacher and radio journalist to statesman owed much to the ambitious vision of two former Australian patrol officers — Barry Holloway and Tony Voutas, who helped found the Pangu Party — along with a clutch of individuals who would become leading figures in the emerging nation, including Albert Maori Kiki, John Guise and Ebia Olewale. Pangu would form PNG’s first independent government and dominate the country’s politics for much of the next half-century. Holloway, one of the first Australians to take PNG citizenship in 1975, chaired the committee that drafted the constitution, became speaker of the first parliament and later served as a senior minister in various governments.

But while Australia had by the early 1970s begun to fast-track the preparation of young Papua New Guineans to assume leadership roles in the post-independence administration, there was still only a handful of competent university graduates in 1975 and none with substantial experience. The success of the first government would rely heavily on a small group of young men who soon became known as the “Gang of Four.” All were still in their twenties when Australia surrendered the reins of government.

Mekere Morauta, the first head of the finance department, and Rabbie Namaliu, a leading academic and diplomat, both went on to become prime ministers and members of the Privy Council. Charles Lepani headed the National Planning Office before becoming a long-term high commissioner to Australia. Tony Siaguru, the first head of PNG’s foreign affairs department, later became deputy secretary-general of the Commonwealth and was eulogised by Ross Garnaut as “the decathlon gold medallist in Papua New Guinea’s national life since independence.”

The inexperience of its politicians and bureaucrats would be just one of the difficulties to face the new nation. Despite the country’s vast natural resources, delivering essential services to a rapidly growing and urbanising population was an enormous challenge, as were maintaining national unity and combating a tide of endemic official corruption that would embroil even Somare himself.

But despite numerous crises and upheavals, and despite the dire predictions of the early Australian doomsayers, PNG would survive and largely succeed as a stable and functioning democracy. And much of that achievement was due to Michael Somare’s unique ability to transcend the historical enmity of PNG’s diverse ethnic, regional and linguistic groups and be widely embraced with the unprecedented accolade of “Grand Chief,” as well as being recognised universally as “father of the nation.”

Through four separate terms as prime minister totalling almost seventeen years and spanning thirty-five years, he became an enduring and stabilising constant of PNG politics. When not seated on the throne he was often the power behind it. And every one of the eight other men to serve substantive terms as prime minister of PNG at one time served under him.

His achievements were vindication of Gough Whitlam’s bold vision for PNG independence, but the credit for delivering it was his. •