“Dear Miss,” begins Letter to a Teacher. “You won’t remember me or my name. [But] I have often had thoughts about you and about that institution which you call ‘school’ and about the boys that you fail.

“You fail us right out into the fields and factories and there you forget us.”

The Letter was addressed to every teacher, every school, the whole system. The “us” (and the “I”) were eight boys in their early teens, sons of Italian peasant families from a hamlet in the backblocks north of Florence called Barbiana. They wrote, nearly sixty years ago, for all of Italy’s poor.

Schools, they said bitterly, are like hospitals that tend to the healthy and reject the sick.

Schools are reserved for those who can get their culture at home.

Schools make boys like us hate study, so the best years for learning are spent “fooling around with sex or fooling around with sport.”

Schools don’t let the poor understand because they’re not allowed to talk about poverty. It’s not nice to talk about such things.

Schools turn maths, history, languages, science, “fine things,” into pathetic exercises, learning for marks, learning for the profit of individuals.

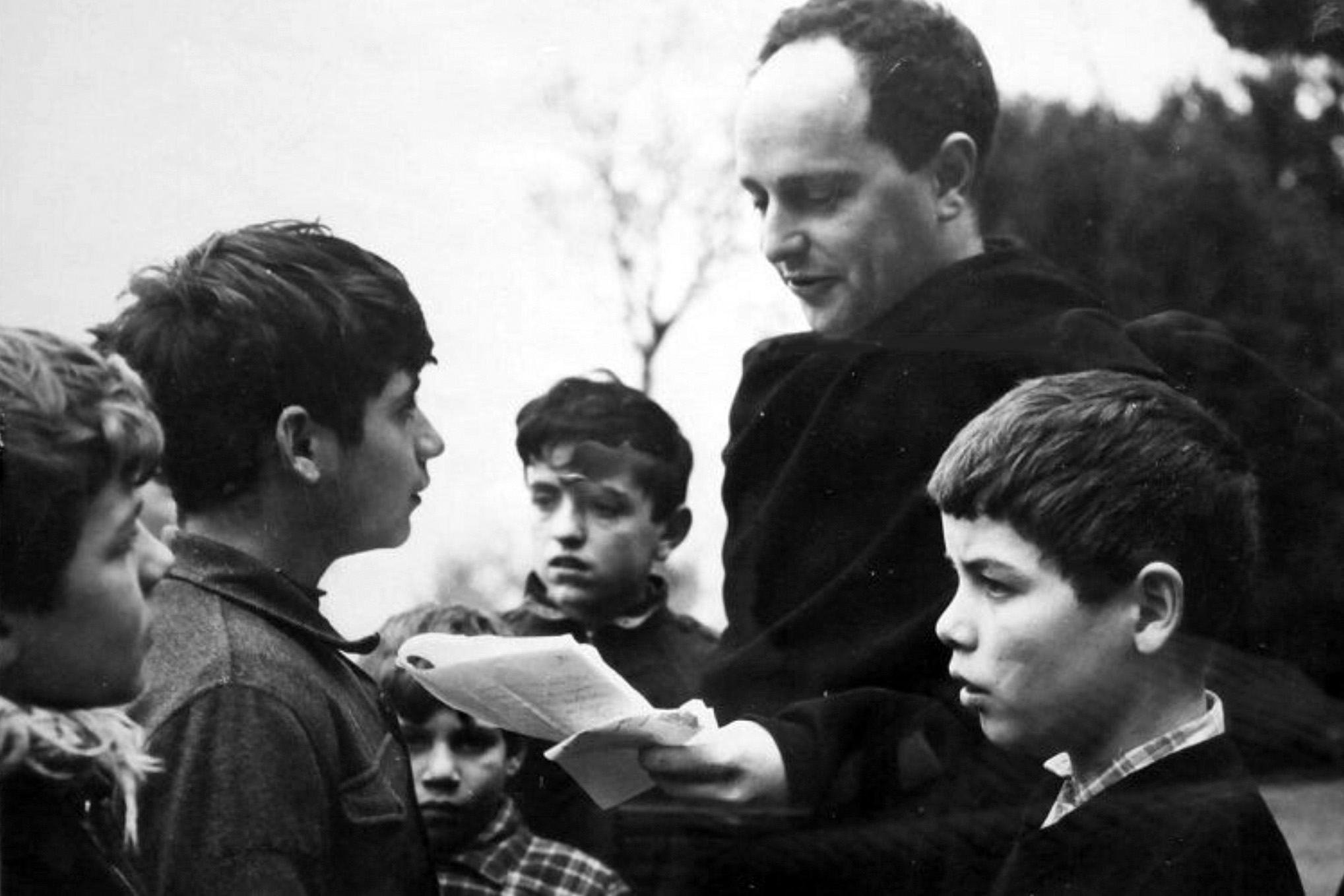

The boys, the authors of Letter to a Teacher, had been required to go to school until they were fourteen. They’d done their five years at elementary school but then there was nowhere for them to go — there was no media inferiore in or near Barbiana. The gap was filled by the local priest, Don Lorenzo Milani.

Barbiana was a huddle of little houses with just one glimpse of riches, a beautiful fourteenth-century church. Don Milani was there because he was a troublemaker. Head office (aka the bishop) had no time for troublemakers, especially not then, in Italy, in the mid 1950s.

The war, defeat and fascism were only a decade away. Then, and for twenty more years, Italy was in transition, or perhaps turmoil or pre-revolutionary ferment, depending on your angle of view. This was the world of Elena Ferranti’s fierce Neapolitan quartet, the first and most famous of them My Brilliant Friend.

Two institutions fought for politico-cultural supremacy, the Church and the Partito Comunista Italiano. Both were anti-fascist (although the PCI had its well-founded doubts about the Church) as well as anti–each other. Within each was an almost comically similar conflict between institutional power and faith. On the one side New Testament Christianity struggled with a hostile Vatican; on the other humanistic Eurocommunism struggled in the coils of the Kremlin. The faiths met in the middle; the institutions did not.

Coming to the priesthood from the high bourgeoisie after a road-to-Damascus experience, Milani was among the new wave of insurgent priests, deeply committed to the Church but not to its orthodoxies. He told a correspondent that he would join forces with the communists to fight against the rich on behalf of the poor but would part company the moment the battle was won.

He’d written a polemic when young with the arrogance of his class and the zeal of a convert; it went straight onto the Index of Prohibited Books. He was controversial, vilified for his “exhibitionist ecclesiastical activism” as a “Jacobin despot,” a demolisher of the Italian school, an inspirer of intolerant classism. And he was lionised, a darling of the left.

On schooling, Milani was at one with many of a broadly left persuasion — including communists such Loris Malaguzzi, founding genius of early childhood education in Emilio Reggio — in believing that children and childhood were to be respected, listened to, and encouraged toward understanding and action in their own lives. The reading list at Barbiana included The Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, a founding leader of the PCI and a casualty of Mussolini’s prisons.

Milani did not like to give religious instruction; his schoolroom bore no religious iconography so that even communist and atheist parents would see that this was not “the priest’s school.” His mission wasn’t to proselytise, or not directly anyway. It was to give the poor what was theirs by right, the right to know and to understand.

Milani’s students came to him resenting both the schooling they’d had and the schooling they hadn’t. “During the five years the State offered me a second-rate education,” they seethed. “Five classes in one room. A fifth of the schooling that was due to me.” They’d been (as they put it in the Letter) chopped out. Look at this pyramid diagram, they instructed. “It looks as if it is chopped out by hatchet blows. Every blow from the elementary years up,” they added, “is a creature going off to work before being equal.”

For the girls of Barbiana the blow came before they even got to school. Why didn’t they come, the boys wondered? Because the walk to and from school was dangerous? Or was it the fathers? “Males don’t ask a woman to be intelligent,” they observe acidly.

Boys and girls alike, this was the “slaughter of the poor” that disposed of Lenu’s brilliant friend Lila in My Brilliant Friend and made Lenu herself fight and battle and fight again until one day, eventually, she arrived in that mysterious world, the university. Like Lenu and Lila the boys resented being excluded from “the culture.”

They had a very Italian view of schooling, as did Milani. His school (in reality just a room in his house, plus himself) was in some respects hyper-traditional. Students worked very long hours, seven days a week. They worked their way through the fundamental disciplines and through reading that included the Gospels, Socrates, Plato and a biography of Gandhi as well as Gramsci.

In other ways, however, Milani’s school was an affront to the system that surrounded it. In a culture that drew an inviolable line between teacher and taught, the boys worked side by side with their teacher and they themselves taught as well as studied.

One visitor found that there was only one copy of each book and the boys used to crowd around it. “It was hard to notice that one was a bit older and was teaching.” Another (one of the book’s English translators) coincided with a group from a nearby orphanage; some of the “old” Barbiana students, now aged sixteen or seventeen, were teaching the younger children. “Gathered around rickety tables, under the trellises, in the kitchen — children of all ages were hard at work everywhere.”

Increasingly Milani and the boys ran a “hospital” that made a point of welcoming the “sick” — the failed, the ejected, the bitter who came to Barbiana as its fame grew. “They had never heard that one goes to school to learn, that to go is a privilege,” the boys report. “The teacher, for them, was on the other side of a barricade and was there to be cheated. It took them one hell of a time to believe that there was no marks book.”

Some of these children who came to a school that welcomed them loved it straight away. “Sandro became enthusiastic about everything in a short time”; for Gianni it was harder. “He had come to us illiterate and with a hatred of books. We tried the impossible with him.” Eventually Gianni came to love not every subject “but at least a few.”

Surrounded by a school system devoted to exams and the advancement of individuals, Barbiana held no exams. Learning for marks and for individual advancement were contemptible, hostile to real learning. What does learning for marks produce? “Masters in the production of hot air and warmed-up platitudes.” Students lose interest in all the fine things they are studying. Languages, science, history — everything becomes purely pass marks.

The best learning is done not by individuals but by individuals working with and for the group, and from doing things for real. How does good writing happen, they ask? “Have something important to say, something useful to everyone or at least to many. Know for whom you are writing. Gather all useful materials. Find a logical pattern with which to develop the theme. Eliminate every useless word. Eliminate every word not used in the spoken language. Never set time limits.” As they worked they helped each other — until all understood, “the others would not continue.”

Each contributed to the labour of all, especially Giancarlo. “Giancarlo took on himself the job of compiling statistics. He is fifteen years old. He is another of those country boys pronounced by you [they turn to face the “teacher”] to be unfit for studying. With us he runs smoothly. He has been engulfed in these figures for four months now… [W]e offered him the chance to study for a noble aim: to feel himself a brother to 1,031,000 who were failed… he was to taste the joys of revenge.”

Letter to a Teacher came from a year’s relentless labour. The project had been suggested by Milani and he came first in the boys’ acknowledgements. “Father Milani… trained us, taught us the rules of writing and supervised our work.” Then came parents (“who helped us simplify the text”), secretaries, teachers, priests, union officials, newspaper men, civic administrators, historians, statisticians, jurists.

The little book was so fierce, so passionate in its defence of the poor and so angry in its assault on the dominant order that the boys feared its reception. “Newspapers of the left and the centre have always applauded any publication on the school of Barbiana,” they said. “After this book, they may join with the right and start hating us.” But, they didn’t, or not at first anyway.

Published in 1967 Letter to a Teacher was an instant sensation, first in Italy — its statistical achievements won a prize usually reserved for promising physics students, and it was even credited with triggering the student uprising of 1968 — and then, as it was translated into one language after another (around forty eventually) a source of astonishment and inspiration to hundreds of thousands around the world, including me.

In the longer run, though, the boys were right to worry. They had worked and written in that brief moment when the world was young and all seemed possible. In Australia, even an august national body could quote Chairman Mao, urging that “a hundred flowers bloom.” But history’s wheel soon turned. Insurgency provoked counter-insurgency, articulated most powerfully by the Reagan administration in the United States.

“If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America a mediocre educational performance that exists today,” a Reagan-commissioned report thundered, “we might have viewed it as an act of war.” “Liberal” and “progressive” schooling had placed the nation’s very security at risk. The antidote was spelled out in What Works: Research about Teaching and Learning, another little book, brilliantly designed and written, as sensational in its time and place as Letter to a Teacher had been, and far more consequential.

The “research” on which What Works relied found unanimously in favour of the tried and the true: subjects, classrooms, timetables, teacher and taught; standards; testing; “performance,” and accountability — not for systems or governments, but for schools and teachers. Ninety-nine flowers could die; one would provide for all.

The movement for more “effective” schools and “evidence-based” teaching gradually seeped through the policies of Australia’s state and federal governments until in 2007 it surged. Accusing the Howard governments of dragging the lead, the incoming Rudd–Gillard government promised an “education revolution.” Within a year or two it had installed NAPLAN, My School, the national curriculum, ACARA and AITSL (now joined by AERO), all institutions that are still with us. The revolution’s language, precepts and policies still dominate official minds.

The substrate of What Works and of all that followed is a bloodless vision of schooling, an agribusiness dream of neat rows of schools and teachers and students sitting up straight, taking what’s put on their plate and doing what they’re told, the kind of schooling that makes students lose interest in all the fine things they study, that turns languages, science, history into the pursuit of marks, that chops out the poor and euphemises them as “welfare families” or “the disadvantaged” or “the long tail.”

On a midsummer’s day in 2017 the papal helicopter landed in a field just below the little hamlet of Barbiana. The Pope had come to Barbiana to pray at the grave of Don Lorenzo Milani and to address a gathering that included some of the boys who’d written Letter to a Teacher, now men in their sixties.

“I rejoice at meeting here those who were pupils at Barbiana,” he said. Milani’s life was accompanied by much bitterness and yes, the Pope conceded, some of it came from the Church. He was in Barbiana to come to terms, to reconcile. “It is not a question of cancelling out history or denying it, but rather of understanding the circumstances and humanity at play.”

The Pope wasn’t going to bag the bishop who’d rusticated Milani or the Vatican operatives who’d put Milani’s writings on the Index (or stir up his own hornets’ nests), but he was going to take Milani’s part. Milani, he said, understood that “one cannot teach without love or without an awareness that what is given is simply a right, that of learning”; Milani was intent upon “giving the word back to the poor because without the word there is no dignity, nor is there freedom or justice.” And then the Pope quoted from the Letter: “I learned that the problem of others is equal to mine. Finding a way out together is politics. Finding a way out alone is avarice.”

So, history’s wheel had turned again, in the Vatican anyway. But in the rather less exalted world of Australian schooling?

Down on the ground, in between the orderly rows of agribusiness schooling, things are happening. Some schools are looking for ways out of the orthodoxy, toward what not always clear. At a recent national conference of government secondary school principals — most of them schools for the poor and the excluded — there was much talk about what they, the principals and their schools had to work with and had to work against; they couldn’t do the right thing by the kids.

Australia’s 9500 mega-schools aren’t about to shatter into tens of thousands of Barbiana-sized schoolets, each with its own charismatic teacher, any more than they’re going to put Year 9s on a diet of Plato and Gramsci (especially not Gramsci!). Agribusiness will not be replaced by permaculture. But there are plenty of schools wanting to edge away from one end of that spectrum toward the other.

They would go for peer and cross-age tutoring of a broadly Barbiana kind (for example) had that been on offer when the post-Covid panic drew billions for “catch-up.” And, what’s more, they would go for it not just because it can be more effective and very much more cost-effective but because it teaches new skills, develops a sense of responsibility, and encourages kids to work on things together.

Nor are too many schools going to bin the marks book. But increasing numbers are trying to use “learning progressions” (or “developmental continua”) to shift from organising student and teacher work around competition based on cognitive speed toward a “student experience” organised around the intellectual progress and the personal and social growth of each.

And while there is no Australian school that could venture the kind of militant collectivism of Barbiana (“finding a way out alone is avarice”!), there are schools, and probably a growing number of them, trying to turn “group work,” “projects” and the like into the systematic development of capabilities in communication, collaboration and learning to learn.

Signs of a turning wheel are harder to find at HQ. The bishops of Australian schooling are not malevolent; if they had an Index they wouldn’t use it. But they are handcuffed and then befuddled. They persist in trying to work through the fantastically complex and ineffectual machinery of the “national approach” and the intimidating, counterproductive apparatus of performance extraction. And, to try to understand what’s going on, they peer through the lenses that came with the machinery.

Why are we no closer to the top five on OECD league tables than when that target was legislated in back in 2012? More: what is to be made of a small blizzard of new and alarming developments? The vocabulary of outcomes, performance, accountability and all the rest is now joined by talk about “classroom disruption,” “discipline,” “school refusal,” “early leaving,” “bullying,” even “violence.” From HQ these look like “problems,” “issues,” “developments,” “trends,” each to be “addressed” by its own “program” or “initiative” or “intervention.” The dots do not connect.

Connected up, what do we see? The look and feel of schools has changed (for the very much better) but the content and organisation of the daily work of students and teachers has not. The “dominant grammar” of schooling has never worked very well for a lot of young people and it is not working for increasing numbers of them for an increasing number of reasons. The dots are disaffection, boredom, resentment, disengagement, humiliation, resistance, sometimes outright defiance. They are canaries in the mine.

Please do read Letter to a Teacher. Those 100-odd pages from another time and another place remind us of how far we’ve come and how far we haven’t, of what kids can do if they’re given half a chance, and of the kind of schooling that every kid should have. •