PERHAPS more has been written about Mahatma Gandhi than any other twentieth-century figure. But most of the English-language biographies and major studies published each year fade fairly quickly into obscurity. Why, then, was India recently engulfed by a paroxysm of outrage when Pulitzer Prize–winning author Joseph Lelyveld’s Great Soul was published in America?

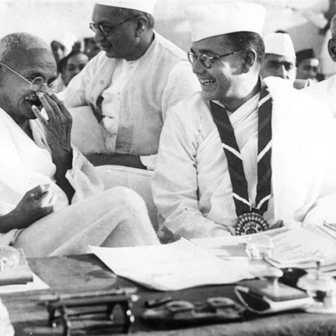

During a long career as a journalist, Lelyveld has covered both South Africa, where Gandhi lived early in his career, and India for the New York Times. His new book, subtitled Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India, demonstrates his knowledge of both countries and is guided by a good reporter’s scepticism. He tells the story of a man who made mistakes, who occasionally did things that seemed to conflict with his own teachings, who wanted to be a saint but could be too much of a politician – but also someone who had a vision, perhaps doomed from the outset, of how life should be lived and how, in Lelyveld’s words, his “recalcitrant country” could provide a model for the world.

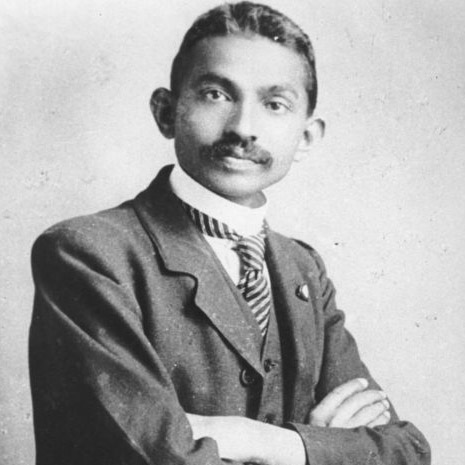

Great Soul is not a full biography and it certainly doesn’t serve as an introduction to Gandhi’s life and times. Lelyveld dispenses with Gandhi’s youth, focusing instead on how the years in South Africa remade a callow lawyer into a political activist who was capable of inspiring mass mobilisation among the disaffected. He is clearly aiming to provide a deeper analysis for an audience that already knows something about his subject. And he obviously respects Gandhi; while his assessments are not all positive, it is clear that he is not merely setting up the Mahatma for a hatchet job.

A threatened India-wide ban on the book was fuelled by a cascade of events: the bans announced in some individual states, outraged speeches by politicians, hostile newspaper headlines and an agitated Indian blogosphere. Why this happened probably says more about the political situation in India than it does about Lelyveld’s book.

The cries to ban Great Soul originated in Gandhi’s home state, Gujarat, which is governed by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. Outrage was also orchestrated in the state of Maharashtra, dominated by the Hindu right, following a lead story about the book in the Mumbai Mirror. While Maharashtra eventually abandoned moves to outlaw Great Soul, it’s likely that many Mumbai bookshops will have declined to stock it given the history of violence against people or institutions associated with books judged critical of some local hero.

That the traditionally secular Congress Party, governing at the national level, toyed with the idea of a ban is even more surprising. India’s law minister, Veerappa Moily, was in favour, and even foreshadowed an amendment to the 1971 National Honour Act that would make insulting the “Father of the Nation” – as Gandhi is called in India – an act of blasphemy similar in gravity to offences against the national flag or Indian constitution (with penalties of up to three years’ imprisonment). Given India’s general criticism of the blasphemy laws of its neighbouring foe, Pakistan, this is the height of irony. Moily denounced the book as “baseless, sensational and hearsay… denigrating a national leader.” Then, after a few days of vacillating, he backed down, explaining that it was a review of the book that had led to the outcry and therefore “there is no question of banning the book as the author has clarified that he has not written what has been attributed to the book.” The allegation of blasphemy evaporated and, in the end, sense prevailed at the centre.

In Gujarat the issue was not dropped so easily. Chief minister Narendra Modi denounced the book as a perversion, accusing Lelyveld of a most reprehensible act, “hurting the sentiments of those with capacity for sane and logical thinking.” He requested that the book be banned across the country and demanded a public apology from the author. The state assembly voted unanimously to ban the volume, with the state Congress Party leader urging the national government to take similar action.

HOW could a book that added very little to what we know of this well-documented life have ignited such passions? And how could it have happened in a democratic country where, moreover, the book was not yet available?

The controversy was sparked by Andrew Roberts’s review, “Among the Hagiographers,” in the Wall Street Journal on 26 March, which was more a character assassination of Gandhi than a serious reflection on the book. Two days later, in an article titled “Gandhi ‘left his wife to live with a male lover’ new book claims,” the London tabloid Daily Mail reproduced the parts of the Roberts review that deal with Gandhi’s attitudes to sex. Interestingly, two days before the Roberts piece appeared, the New York Times had published a very favourable review (“How Gandhi Became Gandhi”) by biographer Geoffrey Ward, who grew up in India. Had it not been made explicit, it would be hard to guess that this and the two other articles were about the same book. Ward’s piece did not raise overly controversial issues and was not picked up by the Indian press.

Roberts, who professes to be “extremely right wing” and is a hagiographer of Gandhi’s opponent, Winston Churchill, commences his review of Great Soul by stating that Lelyveld’s “generally admiring” book allows us to conclude that Gandhi “was a sexual weirdo, a political incompetent and a fanatical faddist – one who was often downright cruel to those around him… professing his love for mankind as a concept while actually despising people as individuals.” The review is full of selective quotations, unwarranted linking of disparate facts and statements, and misinterpretations. It is a catalogue of everything negative, or anything that could possibly be construed as negative, in Lelyveld’s biography, without any of the sympathetic analysis that he also includes. Roberts merely notes at one point that “Mr Lelyveld is not immune” from hagiography, “making laboured excuses for [Gandhi] at every turn of this nonetheless well-researched and well-written book.” In short, under the guise of a review Roberts’s piece pushes another agenda. Gandhi is someone he doesn’t like.

The earliest writings about Gandhi by Western authors were admiring of their subject. Among them, the French pacifist Romain Rolland’s 1924 book, Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One With the Universal Being, did the most to popularise Gandhi in the West. But there were also critical books. American Anglophile Katherine Mayo visited India in 1926, interviewed Gandhi, and in the following year published Mother India, which was to become the most popular book on India in the first half of the twentieth century. It was an apologia for the British subjugation of India, focusing on the topics of filth, disease, sex, disadvantage, illiteracy, the oppression of women, heartless caste practices, the mistreatment of cows, untouchability and Hindu–Muslim enmity, often using Gandhi as an authority to back her argument or to show that he was part of the problem. Gandhi labelled the book a “Drain Inspector’s Report” but, while he pointed out its distortions, he added that “every Indian can read [it] with some degree of profit” to see themselves as others saw them in order to correct their defects.

Revisionist literature on Gandhi and his role in the development of India has continued apace. Authors such as Arthur Koestler (The Lotus and the Robot), Ved Mehta (Mahatma Gandhi and His Apostles) and V.S. Naipaul (India: A Wounded Civilisation) have tried to demonstrate that Gandhi was a reactionary. More recently, Jad Adams (Gandhi: Naked Ambition) produced a debunking volume focusing on Gandhi’s sexuality. Whatever the first sensationalist reviews of his book suggest, Lelyveld’s Great Soul cannot comfortably be placed in this company.

The issues highlighted by the would-be book banners – that Lelyveld claims Gandhi was both homosexual and a racist – are not borne out by a careful reading of his book. Gandhi is shown as a person of his time: someone whose primary concern in South Africa was obtaining justice for his own community rather than promoting the well-being of blacks. Later, when his ideas about race developed as his insights grew, he could acknowledge the narrowness of his vision and seek justice for all.

The reference to Gandhi’s relationship with his soul mate at the time, Hermann Kallenbach, is not a salacious new discovery by Lelyveld. The author is trying to understand the young Gandhi and actually warns that in an age “when the concept of Platonic love gains little credence” details of a relationship and quotation from letters “can easily be arranged” to reach a conclusion that is not necessarily warranted. James Hunt, the most scholarly yet sympathetic biographer of Gandhi’s time in South Africa, and Lelyveld’s source, noted that the relationship may have been “homoerotic” but was certainly not homosexual. Lelyveld notes that this described “a strong mutual attraction, nothing more.”

If anything, this brief discussion comes across as a divergence from the main story Lelyveld is telling. Yet on the strength of these few paragraphs, Roberts and the Daily Mail paint Gandhi as a homosexual. And in a country where there is sensitivity about the Father of the Nation’s honour, and where homosexual activity was a criminal offence until 2009, this was bound to go rapidly viral on the internet. On 29 March Mumbai’s largest-circulation paper, the Mumbai Mirror, ran a front-page story about the outrage under the heading “Book claims German man was Gandhi’s secret love.” Soon all hell had broken loose and Great Soul had become a focal point for opportunist politicians.

The book wasn’t yet available in India, so the calls for a ban were made by people who had not read it. This raises the question of whether the reaction was really about protecting the image of the Father of the Nation (which needs little outside protection) or for some form of political gain. As the social scientist and Gandhi scholar, Tridip Suhrud, observes, any decision to ban any book, even if it is flawed, “suggests a growing intolerance with the culture of discussion and debate.” It is a pity that Indian politicians, while proudly proclaiming their country the world’s largest democracy, seem to be spearheading this growing intolerance.

The farce at least stimulated public debate about the limits of free expression in a country that upholds the importance of this right but feels the need to balance it against the sensitive issue of national harmony. India banned Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in 1988 and in 2003 banned an autobiographical novel by Bangladeshi feminist writer and critic of Islam, Taslima Nasreen. As Time magazine’s correspondent, Jyoti Thottam, commented:

The Indian public is getting a little tired of this particular brand of controversy and the high-minded debate that follows. It seems to repeat itself so often and spares no one, from senior Hindu nationalist politicians like Jaswant Singh [who wrote a sympathetic biography of Jinnah, the father of Pakistan] to progressive activists like Arundhati Roy. And inevitably, the ending is the same – a few political points scored, democratic values compromised slightly and the offending authors suffering little more than a touch of notoriety and the inconvenience of a media mob.

Another commentator pointed out that these bans offer a “no cost opportunity, the small minority of readers in English is not considered a useful votebank, and banning a book offers immediate access to national television.” Perhaps not coincidentally, it has been rumoured that Narendra Modi has been casting his eye on a political role at the national level.

Lelyveld’s response to the outcry was to point out that it was shameful for a country that calls itself a democracy to ban a book “that no one has read, including the people who are doing the banning.” With tongue firmly in cheek, he added, “The book was banned in Gujarat by the great Gandhian Narendra Modi.” One Indian newspaper, the Hindu, quite rightly pointed out that “the Mahatma would have been the first to protest against any suggestion of an obscurantist ban.”

BIOGRAPHIES are often produced by those who love and consequently want to laud their subjects or by those who dislike and so want to denigrate them. Lelyveld has probably come as close as possible to producing an impartial biography of Gandhi. Those who revere the Mahatma may not be overly fond of a book that paints a portrait of someone who was all too human, with the failings that that entails. Those who want to portray Gandhi as a humbug or worse may find some ammunition – but not vindication. The author tries to understand Gandhi in his own terms, and does a reasonable job. There is nothing negative here that is new to those who are versed in the Gandhi story. But still, there is enough for those with strong pro- or anti-Gandhi feelings to gather ammunition for their beliefs.

Indeed, Lelyveld demonstrates the dilemma Gandhi faced in trying to be both a politician interested in national independence and a social reformer who was interested in a certain sort of independence: “neither cause – that of Hindu–Muslim unity nor justice for untouchables – had much appeal to caste Hindus, especially rural caste Hindus, who where the backbone of the movement Gandhi and his lieutenants were building.” In fact, he insightfully notes, “To say that Gandhi wasn’t absolutely consistent isn’t to convict him of hypocrisy; it’s to acknowledge that he was a political leader preoccupied with the task of building a nation, or sometimes just holding it together.”

Lelyveld denies the claims made in the early inflammatory reviews. The book, he writes,

does not say that Gandhi was bisexual. It does not say that he was homosexual. It does not say that he was a racist. The word bisexual never appears in the book and the word racist only appears once in a very limited context, relating to a single phrase and not to Gandhi’s whole set of attitudes or history in South Africa.

In short, Great Soul provides real analysis, not hagiography. Gandhi is a person of his time, with all the baggage that entails. Like all of us, he does not come into the world fully formed. He moves from realisation to realisation. He is allowed to grow, to change.

It has been argued that some Indian politicians might not have welcomed the book because it shows how they have let the Mahatma down. But their politically disingenuous criticisms backfired badly: they ensured that a great many more Indians will read this book than would otherwise have been the case.

Interestingly, almost at the very end of Great Soul, after describing the 2002 massacre of 2000 Muslims and the displacement of 200,000 others in Gujarat, Lelyveld makes the point that those killings “were tacitly sanctioned, even encouraged, by a right-wing Hindu party lineally descended from extremist movements that were banned for a time following Gandhi’s assassination on suspicion that they had been complicit in the murder. That party [the BJP, led by Modi] has held power ever since in the Gujarat state capital named Gandhinagar, after the favourite son who deplored its brand of chauvinism, expressed in a doctrine of national identity called Hindutva,” which is “diametrically opposed to the doctrine of Gandhi.” A cynic might think that this, rather than any reference to Gandhi as a homosexual or racist, was the real reason for the knee-jerk reaction promising a banning of the book.

In the end, for all the bluster, the book was not even banned in Gujarat. While Modi made announcements in the Gujarat Assembly that the book was being banned there, no order prohibiting the book was ever gazetted. Without any fanfare, even he had effectively backed down. One commentator noted that Modi “hoped to win kudos for being the first to ban and now finds himself alone and ridiculed.”

Lelyveld was obviously blindsided not so much by the furore, but by its focus. “I thought the book might be controversial for other reasons,” he writes, “because in my reading of what I am doing I am being somewhat critical of the Indian political establishment for basically jettisoning Gandhi’s goal in this area of social reform and uplift and I identify with his sense that the movement basically payed lip service to his goals. So, I thought that might be controversial – a foreigner making those statements. But in fact no one has paid much attention to that which I consider to be the major theme of the book.”

Now that the book is available in India, some of those in the Indian political establishment may want to read the book – and perhaps ban it. •