Among the many activities at this year’s National Science Week was the Is This How You Feel? project, an exhibition of letters from climate scientists describing how the implications of climate change make them feel. This novel and successful project was the brainchild of Joe Duggan, a masters in science communication student, and I was delighted to contribute.

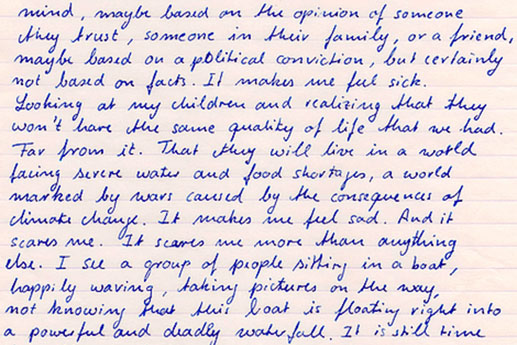

After the original project was launched in Australia, it went global. Letters have now been received from leading scientists all over the world. James Byrne lists why he feels afraid, angry, frustrated, sad and bewildered. Stefan Rahmstorf powerfully likens anthropogenic climate change to a reoccurring nightmare. Lesley Hughes makes clear how much we have to lose, and Katrin Meissner expresses her frustration and fear at the lack of acceptance of the facts. But it is worth pointing out that almost every letter conveys feelings of excitement or hope that it is still possible to make a difference.

Of course, as is the way in modern climate science, not everyone agreed with what Duggan was trying to do. Among the points raised to discredit the project was the argument that, as scientists, we should be completely objective – that no feelings, emotions, reactions or sentiments are permitted on the issue of climate change. It might not come as a surprise to hear that I am at odds with climate sceptics once again.

As scientists, we are trained to be objective. We are trained to be critical, even “sceptical,” and never to take anything at face value. Everything is scrutinised, and our analyses are repeated many, many times. This technique is so important that it is taught in secondary school and is consistent across all the sciences. In plain English: never believe your first result. Only after you have replicated it again and again might it even have a shot at being accurate.

We are also slaves to the scientific method. This approach has been around for hundreds of years and governs how scientists test their hypotheses. The experimental replication explained above is part of it, as is the gathering of suitable data, based on your initial observations, on which your experiment is then performed. But the method also consists of attempting to prove your hypothesis wrong by changing your approach. If you get the same answer to your hypothesis regardless of which (credible) experimental design is used, then this is more evidence that the theory is supported.

Scientists are also extremely critical of each other’s work. The best example of this is the peer review system. Once researchers painstakingly apply the scientific method to prove their hypothesis holds, they submit their methods, results and inferred conclusions to an appropriate journal of their field. Peer review dictates that before the article is even considered for publishing, expert reviewers examine the quality and appropriateness of the experimental design and the conclusions this underpins. In some cases, the study may need to be completely overhauled, or even rejected for publication altogether. Only once a paper has passed peer review can a study possibly be considered as acceptable scientific evidence.

All of the above most certainly applies to climate science – there are no exceptions. We are excruciatingly careful to make sure our results are as robust as possible, and to outline the quantifiable confidence around them as precisely as we can. (Our jargon term for this, which is commonly misunderstood, is uncertainty.) No feelings, emotions or sentiments are involved in reaching our conclusions, ever.

Indeed, even the raw conclusions themselves shouldn’t be subject to feelings. We have employed specific methods to objectively assess a physical state, with our conclusions indicating how and why that state may or may not be changing. The end.

But we are also humans, and as human beings we are permitted to react to the implications of these conclusions. Many thousands of scientific studies on human climate change have been conducted over the past few decades. The overwhelming majority (hovering between 97 per cent and 99 per cent) indicate that human climate change is happening and unmitigated impacts can and will be severe. These impacts are vast and many, including the initiation of physical processes that will further accelerate changes, permanent losses in our ecosystems, and severe financial burdens because of damage to swathes of industries.

I’m not arguing that we should become emotional wrecks when we are faced with the implications of climate change. But a future in which not enough has been done in response is a very worrying prospect. And it is depressing that – despite the plethora of scientific evidence demonstrating climate change is already occurring – we are currently not doing enough to safeguard the future.

So, even as a climate scientist, you can have all these thoughts and feelings about climate change. I don’t believe that interferes with the quality of the work we do. We will always be bounded by the scientific method in obtaining our results and conclusions. This is, at least to us, very clearly separate from the broad implications of our findings. Indeed, in this letters project climate scientist Ruth Mottram highlighted the difference between what we think and feel, and how the latter can be difficult to describe. We do our work because of our passion and natural curiosity to understand how the earth system works, not because we are compelled by negative emotions. These can be, and are, kept separate.

Duggan’s campaign demonstrated that climate scientists are humans, and that fact doesn’t need to undermine our objectivity and credibility. •