The Show: Another Side of Santamaria’s Movement

By Mark Aarons with John Grenville | Scribe Publications | $32.95 | 288 pages

Near the end of the second world war, the membership of the Communist Party of Australia, or CPA, is believed to have peaked at 20,000 members (almost certainly a higher proportion of the population than either of the major parties could claim today). While its influence may have been exaggerated by conservative politicians, its influence in a number of important trade unions was far from insignificant.

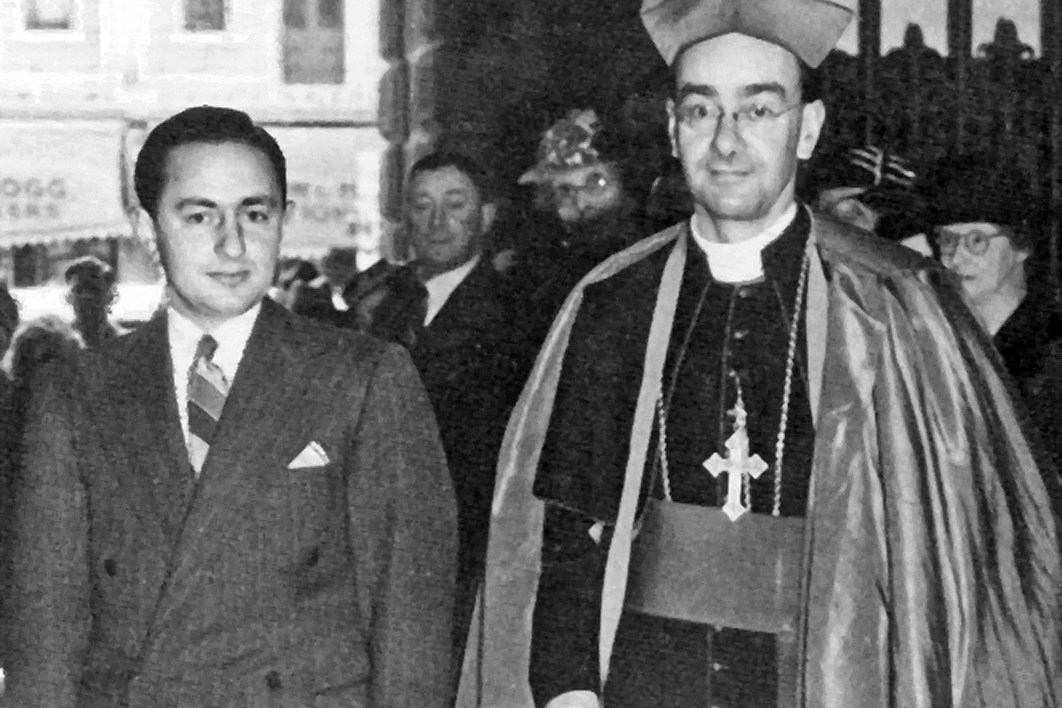

Diametrically opposed to the CPA was the Catholic Social Studies Movement (also known as the Movement or the Show), an opaque outfit formed by a young Catholic lawyer, B.A. Santamaria, with the support of the Australian Catholic bishops. Although it initially focused on eliminating communist influence in unions, the Movement soon adopted the more grandiose ambition of recruiting a majority of Labor Party MPs to its cause — MPs who would implement, when in government, policies based on the Catholic social teaching espoused by Santamaria and his followers. Just as the wartime CPA membership numbers now seem almost unbelievable, it is difficult to imagine an attempt by a church-based organisation to wield that degree of power today.

As a member of a prominent CPA family, Mark Aarons brings an impressive pedigree to his project, although circumstances conspired to extend the time spent on the book — from earliest research in 1991 to publication in 2017 — and to modify the initial plan for a parallel history of the CPA and the Movement. Instead, Aarons offers “an analysis of the impact of Santamaria’s decision to model his Movement… completely on the Communist Party.” Given the dominance of Joseph Stalin’s brand of communism in the 1940s, Aarons contends that the chief characteristic of such emulation would necessarily be Stalinism.

Aarons knows the communist side well; for the Movement perspective, he is assisted by collaborator John Grenville, a Catholic who operated as an undercover member of the Show within the union movement. But some of the most interesting revelations in the book come from declassified ASIO files. Because the Movement was, of necessity, engaged in intelligence gathering, it is perhaps not surprising that links developed with the national intelligence agency. ASIO certainly appreciated much of the information it received in this way, but Aarons records that at least one Movement agent was viewed as unscrupulous, peddling biased and unreliable information (presumably a perennial problem in espionage).

More disturbing from a democratic perspective is the fact that the traffic in information ran the other way as well. As Aarons notes, even if that information was unclassified, “it still sustains the case of ASIO’s critics that it was directly involved in assisting a significant player in Australian politics.” Not surprisingly, Santamaria long denied a Movement–ASIO link, only admitting the truth in 1990.

The cloak-and-dagger theme is evident in much of the book. One vivid instance is a longstanding puzzle over how a vital Movement document fell into the hands of the CPA in 1945. While it suited his purposes, Santamaria supported the story that a careless bishop had left his copy on a train (which was found, conveniently, by members of a CPA-controlled union). Aarons exonerates the bishop, arguing that the leak came from “within” — not a possibility Santamaria could afford to admit.

In keeping with his theme of the CPA and the Movement sharing common methods of operation, Aarons describes internal union battles in considerable detail. On the CPA side, one of the most intriguing figures is the Waterside Workers’ Federation’s Vic Campbell. Neither a teetotaller nor a pacifist, Campbell is suspected of being a double agent (although his story is sufficiently complex that it would be unwise to rule out triple-agent status). Even allowing for the seriousness of the issues involved, Campbell seems to have owed more to Maxwell Smart than to John le Carré.

More broadly, not much that happened within the unions of the period, and especially during union elections, would receive a ringing endorsement in any reputable guide to democratic governance. Self-serving rule changes and rigged elections were not unusual and (in the case of Movement unions) employer donations hardly suggest a vigorous pursuit of members’ best interests.

Two of the most important Movement-controlled unions (the Clerks and the Shop Assistants) became associated with a US-controlled international unions body with the mandatory CIA connections — and with CIA money. Given the ongoing revelations about today’s sweetheart deals between the “Shoppies” and employers, it’s clear that some habits die hard. (If the union hadn’t re-affiliated with Labor, it’s likely that same-sex marriage would have been legislated several years ago and certain members of the right faction may never have made it into parliament.)

As seen by Aarons, the CPA and the National Civic Council (as the Movement became after 1957), equally undemocratic, had lost most of their relevance long before the end of the twentieth century. For the CPA, international events — the new Soviet leadership’s denunciation of Stalin, the denunciation of the denouncers, the Prague Spring — would result in three separate Australian communist parties by the early 1970s. For its part, the National Civic Council underwent what Aarons describes as a schism after its model, in which unions were effectively “run” by an outside body, became unsustainable. The victory of Lindsay Tanner’s team in the Victorian branch of the Clerks’ Union in 1988 was clearly a seminal moment.

Completing Aarons’s picture of the Movement as Stalinist in its operational behaviour was Santamaria’s self-elevation to cult status. “As undisputed leader of the Show,” writes Aarons, “he wrapped himself in an aura of infallibility.” While some may find the Stalinist parallel a stretch, it is certainly the case that the authoritarian Santamaria seemed to share with his communist contemporaries a lack of enthusiasm for pluralist democracy. Aarons endorses the view that Santamaria was essentially railing against modernity, a difficult battle to win in a free society.

Assisted by Grenville, Aarons sheds new light on the role of Santamaria’s Movement, and especially its relationship with ASIO and — at a time when unions mattered — within key trade unions. It is a useful addition to the scholarship on an important aspect of cold war Australia. •