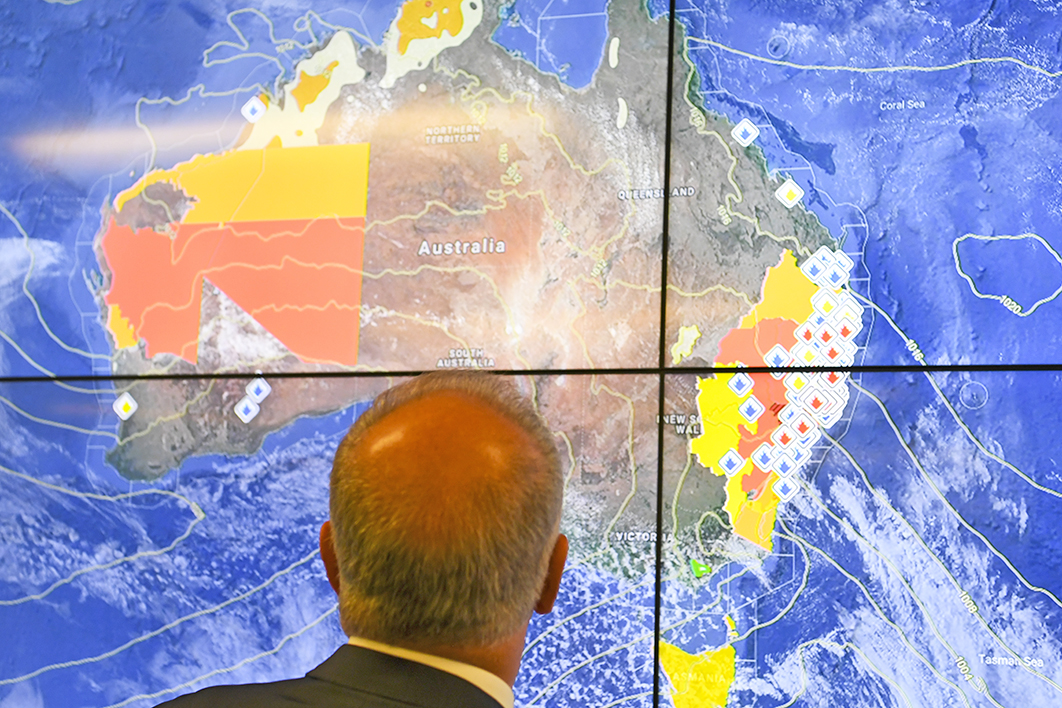

It’s scarcely an exaggeration to say that eastern New South Wales has been on fire this week. Around a million hectares have burned, almost as much as the area destroyed by the last three fire seasons combined. Three people have died, at least 150 properties have been destroyed, and Australian Defence Force reservists are on call if extra help is needed to get the blazes under control.

While most of these fires have broken out in the northern half of the state, on Tuesday this week the forecast of unprecedented catastrophic fire conditions was extended to the Greater Sydney, Illawarra and Hunter regions. In areas where the largest and most troubling fires were already burning, the forecast strong winds left fire services extremely concerned that the worst was still to come. Resources were paper thin, with 950 firefighters currently on the ground.

This is spring, remember. And let’s also not forget the fifty fires currently burning in Queensland, or the fires that hit the Sunshine Coast in October.

The forecast category of catastrophic fire conditions emerged from the inquest into Victoria’s 2009 Black Saturday fires, which claimed 173 lives. With the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index exceeding 100, this is a treacherous combination of gusty winds, high temperatures, low humidity and extreme dryness. Any fire that ignites will quickly reach intensities and move at speeds that place properties and lives in imminent danger.

Conditions like these could have occurred before the category was defined, but their frequency and intensity are on the rise. Australia’s fire seasons have increased in intensity and length, and further increases are projected, most notably during spring. Extreme bushfires are also increasingly intense and frequent: in the case of Victoria, their average frequency has doubled since 1900. Bushfires that form their own weather systems and develop pyrocumulus clouds are projected to occur more frequently, especially in spring, over the next fifty years. And extreme temperatures — a key ingredient in extreme fire weather — are undoubtedly on the rise.

So let’s be crystal clear about this. Climate change is part of Australia’s bushfire landscape.

This is not confined to Australia. Global wildfire danger has increased since at least the 1980s. Climate change made Canada’s wildfire season of 2017 twice as likely to have occurred, and detectable climate change signals were behind the 2015–16 fire seasons in North America and Australia. The fire season in the United States is also lengthening — so much so it has overlapped with Australia’s over the past couple of years. Unprecedented fire conditions, impacts and costs plagued California during its 2018 and 2019 seasons.

How have Australian governments responded? NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian answered a question this week about the role of climate change in the fires with a curt, “Honestly, not today.” Barnaby Joyce blamed Greens policies (a claim that was quickly fact-checked and found to be wrong), and deputy prime minister Michael McCormack notoriously slammed anyone who linked the fires with climate change as “raving inner-city lunatics.”

If now isn’t the right time for discussion and action, it’s hard to imagine when will be. How many times will a state of emergency be declared before a conversation about bushfires and climate change is welcomed?

The Climate Council has released numerous reports linking bushfires and climate change, with no notable response from the government. Together with more than twenty other senior emergency personnel, former Fire and Rescue NSW commissioner Greg Mullins attempted to convene a meeting on climate and bushfires with prime minister Scott Morrison and his colleague David Littleproud but was “fobbed off.”

Strikingly similar discussions about the relationship between climate change and bushfires have been sparked by a spate of other recent fires, including Tathra and Queensland in 2018, Tasmania early in 2019, and the Blue Mountains in 2013. These, too, were ignored by the federal government.

This attitude extends to climate change in general. Just last month, a parliamentary petition requesting the declaration of a climate emergency, signed by more than 400,000 people — the biggest e-petition ever submitted — was thrown out of parliament, despite more than 1180 jurisdictions across twenty-three countries (including sixty in Australia) having made their own declarations. When 11,000 scientists from across the world declared that the adverse effects of climate change are already here, the government was again silent.

In its Global Warming of 1.5°C report, published late last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned of the devastation further temperature increases will wreak on the Great Barrier Reef, yet our emissions-reduction targets remain woefully inadequate. The recent 300,000-strong climate marches have also fallen on deaf ears, with the government not only ignoring those voices but also threatening to punish harshly those who protest.

This failure to recognise the impact of rising temperatures and respond to majority public opinion is bewildering. Whether it’s manifested in bushfires, heatwaves or coral bleaching, climate change is here, now, and we must deal with it. As Margaret Thatcher said way back in 1989, “Every country will be affected and no one can opt out.” No amount of deflecting will change that. •