John Grey Gorton: Australian to the Bootheels

Paul Williams | Connor Court | $19.95 | 100 pages

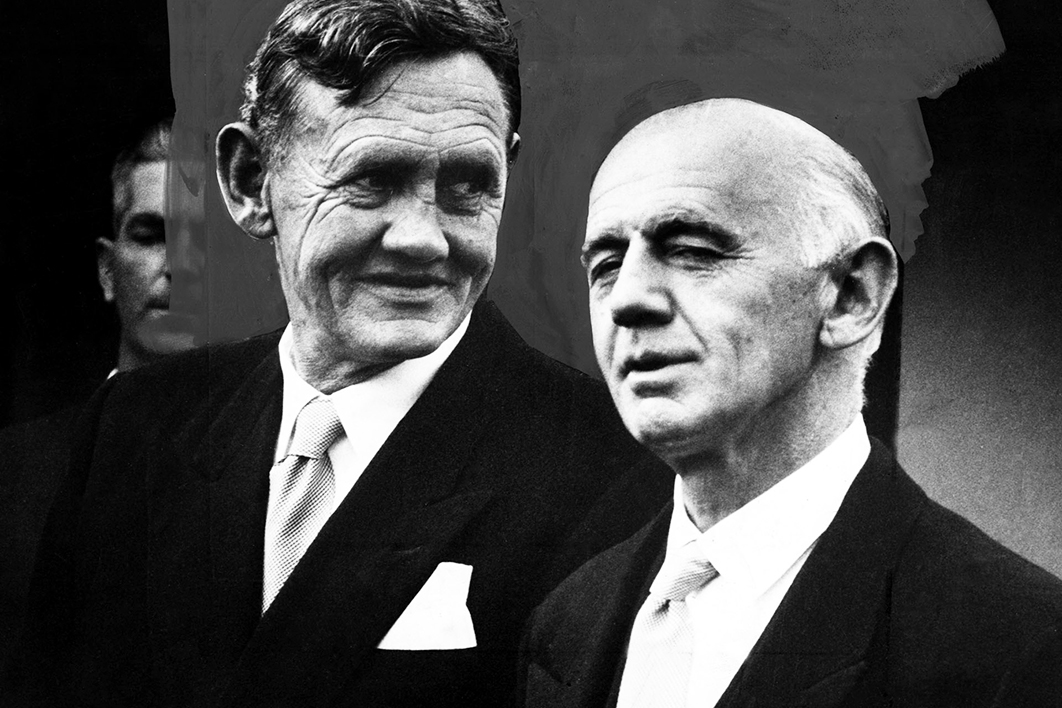

John Gorton might well have been the most self-amused of all of Australia’s prime ministers. Once asked to describe the sort of man he was, he replied that he was six feet tall and weighed about twelve stone. Later, speaking in 1998 with Griffith University lecturer Paul Williams, he described himself as Australia’s best prime minister.

That assessment, like that first quip to an overly credulous TV interviewer, is sure to raise eyebrows. But Williams takes it seriously. He believes that historians have typically taken a “myopic” view of the man who occupied the Lodge from 1968 to 1971. They have described his leadership skills as poor, ranked him as a below-average prime minister, and apportioned him overwhelming blame for the results of the 1969 election, at which the Coalition government, though winning another term, suffered a 7 per cent swing and the loss of sixteen seats.

In this biographical study — one of a series commissioned to rectify a lack of knowledge of leading figures from Australian history — Williams tries to correct the record while explaining why he still concurs that Gorton was a below-average prime minister.

There’s a paradox here that echoes the biographical subject (“the most paradoxical individual to hold Australia’s highest public office”) and this series (“scholarly rather than academic”). What emerges, however, and is valiantly argued, is that Gorton was not simply a placeholder between Menzies and Whitlam, as so many imagine, but rather an active and potentially transformative prime minister — a man who could have been great but who fell far short largely because of his own indulgence and amusement.

Born in Melbourne, or perhaps Wellington, in 1911, Gorton was the illegitimate son of a bigamist orchardist and a Catholic barmaid whose surname was Sinn. His upbringing was materially comfortable but emotionally deprived. When his mother died of tuberculosis, he was sent into the care of his father’s first wife, who also cared for Gorton’s elder sister. The nine-year-old had not known of the existence of either, yet recalled barely shrugging at the news.

An establishment education at Sydney Grammar and then Geelong Grammar was followed by a stint at Oxford, where he gained a pilot’s licence, a blue in rowing, and a wife, in the person of Bettina Brown. Vague hopes of becoming a journalist dissipated when his father died and Gorton inherited his citrus orchard at Kangaroo Lake in northern Victoria.

Like many of his generation, Gorton came of age during the second world war. As an RAAF pilot, he crashed his plane four times over four years, the second time most seriously, transforming his smooth good looks into a crumpled visage. Explaining his later tendency to speak with his head down, Gorton said that he didn’t think anyone else wore as much of their backside on their face. A career in local government after the war was cut short by election to the Senate in 1949.

Like many of the “forty-niners,” Gorton went into politics believing that it was possible to build a postwar world “in which meanness and poverty, terrorism and hate, will have no part.” He was convinced of his ability to build that world. Asked what he thought of his colleagues, he remarked, “Not much. I’m the best of them.” Notwithstanding that belief, he spent nine years on the backbench, eventually holding his first ministry — the navy, typically a training ground for new ministers — from 1958 to 1963. He later claimed that he had “built the modern navy” in that time.

More significant was his appointment to what became the education portfolio at a time when the federal government was increasingly active in the area. But he didn’t make it into cabinet until after Robert Menzies had retired in 1966, and was not a part of the government leadership group until October 1967, when prime minister Harold Holt decided the Senate needed a firmer hand and had Gorton appointed leader of the government in the Senate.

The timing was impeccable, and so was Gorton’s judgement. Perceiving a growing scandal around the misuse of government VIP aircraft, he reacted with a shrewd and casual insouciance by tabling — with a shrug — flight records whose existence the government had hitherto furiously denied. The favourable atmosphere this created allowed him to vault over more experienced colleagues in the leadership ballot that followed Holt’s death in December 1967.

It was a time of considerable political difficulty for the Liberals and their Coalition partner, the Country Party. Labor had an articulate and appealing leader in Gough Whitlam; the Coalition was beset by divisions and animosities; public support for Australia’s military commitment in Vietnam was waning; and a generation of critical journalists had arrived in the Canberra press gallery.

In Williams’s reckoning, Gorton could have risen to meet these challenges, not least because his earthy nationalism, liberalism and rugged appearance struck a chord with the public and suggested a new direction for a two-decades-old government. “We had reached a stage where we were on top of a mountain, and we had to decide whether we stayed up there or go out in various directions,” Gorton later told Williams. As prime minister, these directions were given the catch-all term of “Gortonism,” a highly individual set of preferences including centralism over federalism, prime ministerial autonomy over cabinet government, and greater spending on social welfare.

The problem was that each of these preferences infuriated members of Gorton’s party. Liberal state premiers, conscious of the federal government’s continued growth, protested at Gorton’s moves to extend Commonwealth sovereignty over the continental shelf. Cabinet colleagues were driven to near-madness by Gorton’s unilateralism, evident in his protecting MLC Life Insurance from foreign takeover and in negotiations over oil discoveries in the Bass Strait. “Get this into your head,” Country Party leader John McEwen told Gorton while explaining that consultation was a vital part of the Coalition agreement. And Gorton’s insistence on increased social spending made treasurer Billy McMahon irate to the point that he all but disowned the 1969–70 budget.

One effect of that increase was a 5 per cent cut in defence spending, which raised the hackles of the anti-communist hardliners in the Democratic Labor Party. Given that they had threatened to withhold preferences from the government in 1968, it is hard to know why Gorton was happy to antagonise them again in 1969. But he compounded the offence by signing off on a speech by external affairs minister Gordon Freeth in which Australians were told not to panic if the Soviet Union extended its influence into the Indian Ocean. The DLP made good on its threat and withheld preferences when the election was called for 25 October 1969, forcing Gorton to campaign on an unwieldy program of increased social spending and greater national security.

Gorton indulged himself during that campaign by allowing rumours to proliferate about McMahon’s role in a re-elected government. This distraction, which fed stories of disunity and division that could have been stopped with a single denial, astounded observers. “I have never experienced such a hopeless Liberal–Country composite government campaign,” wrote former Country Party leader Artie Fadden.

Williams tries to defend Gorton from what followed, noting that the government’s support at the 1969 election was equal to its performance in 1967, when the VIP scandal was reaching its apogee and itchy government members were fretting about Holt. This, says Williams, “clearly undermines any claim of Gorton as sole or principal architect of the Coalition’s near-defeat.” The 1969 result certainly lends weight to the argument that the government’s fortunes were in long-term decline, but it also shows just how valuable an opportunity Gorton squandered with his insistence on behaving (in his own words) “precisely as John Grey Gorton bloody well decides he wants to behave.” By the time of the election, this willfulness had earned him the disapproval of censorious opponents. Gorton was unrepentant: “I like a party where I can sing and dance and yarn. Yes, I even like talking to women! How else can I keep in touch with what people are thinking and saying?… Do they want me to live in an ivory tower and meet only diplomats and politicians? Well, damn it, I’m not going to.”

The results of the election put paid to that kind of freedom. The loss of so many seats — including Freeth’s — saw Gorton’s leadership challenged by McMahon and national development minister David Fairbairn. Gorton survived, but in Williams’s account his eventual demise in March 1971 was now almost inevitable. So, too, in Williams’s telling, was the demise of the government, which followed twenty-one months later.

Perceptions that the period between Menzies and Whitlam was a shapeless interregnum have been commonplace for years. One valuable feature of this book is Williams’s effort to show otherwise by setting out the policies and actions that, he argues, make Gorton a “bridge” between the conservatism of the Menzies years and the progressive liberalism of the Whitlam government. Whether it was his nationalism, his enthusiasm for the National Film and Television Training School, or his unapologetic moves to extend the power of the Commonwealth, his record shows an ageing and divided government responding to the hopes and demands of an emerging generation.

While Williams is remiss not to include the McMahon government in that bridge, given its attempts to chart a new way forward, his book draws attention to a vital period in Australia’s history and a significant figure who was vastly more complex than a description of his height and weight, or even his claim to be best prime minister, might suggest. •

The publication of this article was supported by a grant from the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.