To borrow from Hemingway, Bangladeshi prime minister Sheikh Hasina’s downfall this month, after fifteen years of increasingly iron-fisted rule, came about in two ways: gradually, then suddenly.

All the signs of the brewing discontent were there. After coming to power in 2009, Hasina quickly established an implicit contract with both the Bangladesh people and the country’s foreign partners. She would deliver economic development and political stability, including keeping Islamist and Jihadist forces at bay, but there was a price to be paid: flawed elections — leading to de facto one-party rule — rampant corruption and widespread human rights abuses by state agencies.

Initially, it worked. But Hasina’s authoritarian tendencies increasingly grated with Bangladeshis. She undermined the independence of the civil service, the judiciary and other key institutions, and rammed constitutional amendments through parliament aimed at keeping power. Her party won three dubious elections using a combination of ballot-stuffing and opposition boycotts. Hundreds of thousands of people were hit with spurious charges, according to human rights researchers, and around 600 disappeared at the hands of the security forces.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh’s “economic miracle” was beginning to unravel. The country’s shaky economic foundations were exposed when the country emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic with the country’s garments sector — which accounts for 85 per cent of all exports — having suffered badly. Then, when Russia invaded Ukraine and commodity prices spiked, the country’s import bill skyrocketed.

The patronage networks Hasina had built began to weigh down the Bangladeshi economy, stymying chances of a recovery. To protect her supporters, Hasina’s government and its central bank made a series of poor decisions that only compounded the problems. The tycoons she installed at the helms of local banks saddled the lenders with bad debts (much of the money appears to have ended up offshore). As one economist in the capital Dhaka told me late last year, “Bangladesh has strong fundamentals but it’s encountering a self-made crisis — one mainly driven by really bad policies.”

While official figures continued to record solid GDP growth and inflation remained at around 10 per cent — well below Pakistan and Sri Lanka, for example — it was widely believed that Hasina’s government was fudging the numbers. Inflation data was now coming out of the Prime Minister’s Office rather than the statistics division, and was often delayed. Growth figures that briefly pushed the country’s GDP per capita above that of neighbouring India were viewed with scepticism.

In the real economy, meanwhile, people were hurting. By late 2023, one in five poor households were skipping meals, and some were going whole days without food. The effects were felt most painfully among the urban poor.

These economic challenges coalesced with growing anger at the government’s authoritarianism. Hasina’s iron fist was evident ahead of the election in January this year, when she checkmated the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party, or BNP, by breaking up a major rally in Dhaka and arresting its leaders. Detainees were offered deals if they switched sides; when they refused, they were denied bail. Unsurprisingly, the BNP boycotted the vote. With no genuine opposition parties in the race, Hasina’s Awami League and its allies won 95 per cent of seats, leaving the rest to quasi-rivals to give the parliament a token opposition.

In the days after this “selection,” as it was dubbed by Hasina’s domestic critics, her party was exultant; despite the challenging domestic circumstances, she had pulled off another win. The main threat, as the Awami League saw it, had been from abroad, as the United States, in particular, had been pressing hard for a credible election. The decision to lock up BNP leaders attracted no international action whatsoever. Among Bangladeshi officials, it was widely understood that India, Hasina’s chief ally, had convinced the United States to back off.

But the real threat to Hasina’s regime was always likely to come from within Bangladesh. When I visited shortly before the election, most people seemed convinced that the government was unsustainable — all that was unclear was how and when it would fall. “This government is done,” one prominent journalist told me. “People can’t take much more of it.”

Even Awami League officials were worried, particularly about the state of the economy, which they knew was far worse than on paper. Without immediate reforms, they feared, an economic crisis would bring the government down. As one said, “The cancer has set in — we just don’t know how bad it is.” In a January report for International Crisis Group, my colleagues and I warned that “the government’s prospects for the months ahead could darken” and that Hasina may resort to ever greater violence to hold on to power.

The government had been expecting a post-election economic bounce that would help turn things around. Instead came a slew of embarrassing corruption scandals implicating the former police chief, tax officials and even a member of Hasina’s own household, a domestic worker who had apparently managed to accumulate a fortune of around A$50 million and was flying around Dhaka in a helicopter. The government, meanwhile, avoided tough reforms; inflation remained stubbornly high and foreign exchange shortages continued.

In the end, it was student-led protests that brought down Hasina’s government. The students had launched their movement on 1 July after a court reinstated controversial quotas for government jobs. While their anger was piqued by inequitable access to jobs, the issue was inflected with deep political symbolism. Under the quota, 30 per cent of government jobs went to the descendants of “freedom fighters” — those who had fought in Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971. In practice, that largely meant Awami League loyalists. It was a way for Hasina — whose father led the country’s independence movement — to both dispense patronage and stack the civil service with supporters.

The quota reinstatement also touched on the issue of judicial independence, which Hasina had assiduously undermined — to the point of allegedly detaining the then chief justice and, in 2017, forcing him to resign after he ruled unconstitutional an amendment giving parliament the power to sack judges. Within Bangladesh, the recent quota reinstatement order was widely perceived as just another example of the courts doing Hasina’s bidding.

Nevertheless, Hasina could probably have neutralised the threat from the quota movement if she had chosen to meet the students and negotiate. When challenged, though, she made fatal errors of judgement, insulting the students and setting the police and her party’s thuggish student wing onto them. Images of this brutal crackdown spread on social media, bringing more people onto the streets. The security forces responded with more violence, leaving more than 300 dead, but the protests only grew larger.

In the end, it was the army’s refusal to enforce Hasina’s curfew order on 4 August that sealed her fate. The following afternoon, she fled by helicopter minutes before thousands of protesters stormed her official residence.

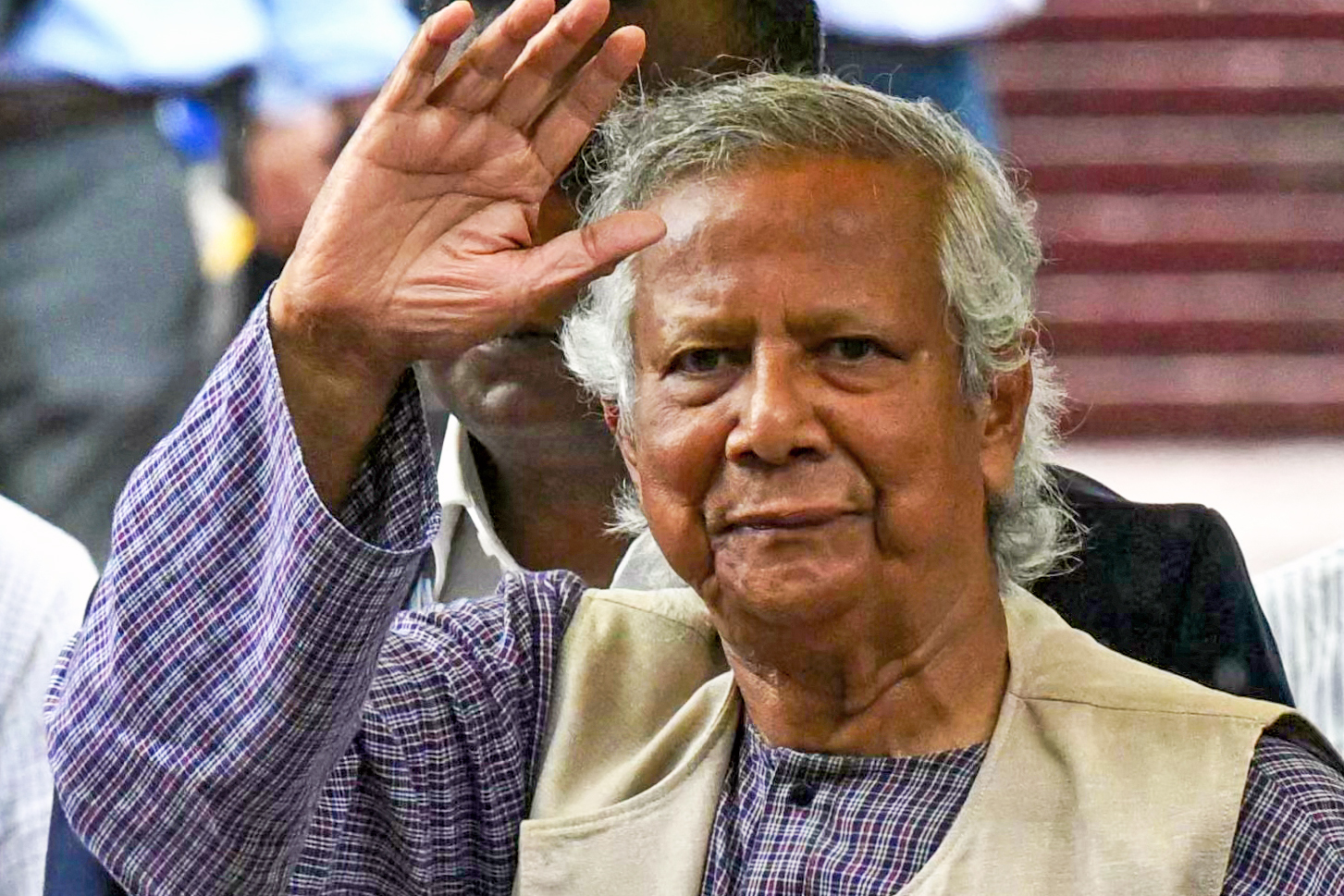

Bangladesh now has an interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, the widely respected and non-partisan figure put forward by student leaders in the aftermath of Hasina’s abrupt exit. It is a remarkable turnaround for Yunus; provoked by his brief flirtation with politics in 2007, Hasina had waged a vendetta against him since her return to power in 2009. She removed him from the microfinance bank he founded in 1983 and hit him with politically motivated charges; in January he was sentenced to six months’ prison for labour law violations but was released pending an appeal.

With Yunus at the helm and the students by his side, there is a heady optimism on the streets of Dhaka — encapsulated in striking street art — and many are demanding deep political and economic reforms to ensure Bangladesh never falls under a Hasina-like tyrant again.

So far, there have been some positive signs. Yunus’s cabinet is the most diverse in Bangladesh’s history, and reformers and respected technocrats have been appointed to lead the Supreme Court and central bank. Security, too, seems to be improving as police return to work after a week of chaos; in the days after Hasina fled, Bangladesh endured a wave of crime and violence, including politically motivated attacks against Awami League supporters that left scores dead. Hindus, who make up 8 per cent of the population, were also targeted, although it seems this was primarily because of individuals’ affiliation to the Awami League, which has long positioned itself as the protector of minorities.

For all that optimism, it is important not to underestimate the challenge Yunus and his cabinet face. He has described the protest movement as a “second liberation” (a reference to Bangladesh’s independence war against Pakistan) and a “student-led revolution.” Certainly, it is a movement unlike anything Bangladesh has seen since independence. The old order, though, has hardly been swept away. Hasina’s cabinet and many party leaders may have gone underground — the law minister was recently arrested trying to flee Dhaka by boat — and some of the more corrupt members of the bureaucracy have been shunted aside. Most bureaucrats, though, remain in their positions.

As well, the interim government’s options are limited. It doesn’t have the legal authority to pass legislation or amend the constitution; instead, it will have to govern through orders, policies and regulations before eventually organising elections. Yunus will need to do this while maintaining a degree of consensus between key centres of power, including the army, student leaders and existing political parties.

So far, the deal seems to be holding, in part because the army doesn’t appear to have political ambitions. Its chief, Wakar-Uz-Zaman, is a distant relative of Hasina, and to the extent he intervened — by refusing to enforce her curfew order — he seemed to do so reluctantly. The likely alternative would have been to kill hundreds, maybe even thousands, in the streets. The army leadership would probably have been hit with sanctions, while rank-and-file soldiers would have lost lucrative UN peacekeeping jobs. (Bangladesh provides 10 percent of all peacekeepers.) Siding with Hasina could have torn the military apart.

And so, when the students proposed Yunus to lead the interim administration, Wakar-Uz-Zaman — who had only taken up his position two months earlier — readily agreed. The army seems to have learned its lesson from a long stint in charge from 1975 to 1990 and a shorter intervention in 2007–08. Both times, the Bangladeshi people demanded a return to democracy and the army was forced to hand back power. It now prefers to stay in the background, as far from the country’s messy politics as possible. Yunus, and many others, will be hoping it stays that way.

So what comes next? The Awami League and the BNP — which many see as little better than Hasina’s party because of its chequered track record of governing in the 1990s and early 2000 — are still the strongest political forces in the country. Both are demanding elections within three months, in line with the constitution. Although the interim administration could start tackling the country’s economic troubles and begin the long work of rebuilding the independence of government institutions, such a short window would not provide enough time for any meaningful reforms.

The student leaders — some of whom are now household names — are instead hoping for at least two years of interim rule, which might also give them time to set up a political network that could compete in future polls. It’s not clear how interim rule could be extended in this way given the constitutional limitations, but talk has already turned to constitutional workarounds and few analysts think elections will be held within ninety days.

The Awami League’s fate is a divisive issue. Following the bloodshed of July and early August, many would like to see the party banned; there have also been calls for Hasina to be tried at the tribunal she set up to prosecute war criminals from the 1971 conflict, many of whom were later executed. Last week, Yunus’s home affairs adviser told journalists he believed Hasina should return to Bangladesh and rebuild her party. His comments sparked immediate protests, and a few days later he was reassigned to the less important textiles and jute ministry.

Banning the party would almost certainly be counterproductive. For all the damage to the Awami League’s image among the wider public, party loyalty runs deep in Bangladesh — as was evident in the ultimate failure of Hasina’s efforts to destroy both the BNP and the Islamist party Jamaat-e-Islami.

And then there is the economy. To get it back on track, Yunus will face some uncomfortable trade-offs. If he goes too hard against the cronies he could create instability and spook international buyers of Bangladeshi garments, which are central to the national economy. He will also need to try to insulate the most vulnerable Bangladeshis from the harsh impacts of some reforms, which could easily erode support for his administration. An inescapable reform like exchange rate depreciation, for example, will almost certainly push up prices because Bangladesh is so heavily reliant on imports.

It is here that other countries, including Australia, can play an important role. The interim government will need a combination of technical and financial assistance to navigate what is likely to be a turbulent period. Australia should also look to expand opportunities for Bangladeshi students, particularly through the Australia Awards scholarship program. If there is one thing we have learned about Bangladesh in recent months, it is the awe-inspiring capacity and determination of the country’s youth.

Hasina’s downfall should also prompt reflection in foreign capitals, including Canberra, about their role in perpetuating her rule. For too long, they bought Hasina’s narrative that she was the only political leader they could rely on. As a result, they largely ignored the political aspirations of the Bangladeshi people. This means there were few consequences when Hasina staged fraudulent elections to perpetuate her rule and then inflicted terrible violence on her own people. Australia has also been silent on the persecution of Yunus.

To the extent Australian governments have given much thought to Bangladesh, it has been as a recipient of aid (including for the million-plus Rohingya refugees from neighbouring Myanmar) and as a potential source of jihadist activity and irregular migrants. A change in attitude had begun, though, after increased geopolitical competition in the Indo-Pacific saw China ramp up its engagement with Dhaka, and Bangladesh’s economic growth caused bilateral trade to increase sixfold in just a decade.

More than 50,000 Bangladesh-born people live in Australia, not to mention those of Bangladeshi descent who were born here; in July, this diaspora was active in drawing attention to Hasina’s crackdown on protesters, staging protests and speaking to local media. Yet when foreign minister Penny Wong visited Dhaka in late May — just a month before the protests broke out — democracy and human rights rated barely a mention. Aside from advising Australians to reconsider their need to visit Bangladesh, the government also said very little about the crackdown on the recent protests. With Muhammad Yunus in charge, an opportunity has come to recast the relationship and support an administration that better reflects Australia’s values.

Bangladesh’s future, though, is very much being written inside the country. Muhammad Yunus hopes that restoring his country’s democracy will be the final act of a remarkable career. It is undoubtedly his biggest test yet. •