The Hero’s Way: Walking with Garibaldi from Rome to Ravenna

By Tim Parks | Harvill Secker | $35 | 384 pages

Look up at the street signs in most Italian towns and you’re likely to score at least two out of the three names that make up Italy’s holy trinity. There will be a Via Cavour, named after Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour (1810–1861), the centre-right prime minister of Piedmont who drove the push for a unified Italy in the mid nineteenth century. You may stumble across a Piazza Mazzini, named after the intellectual powerhouse of the movement, Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872), whose writing from exile framed what became a compelling argument for national unity. But there’s one name that you’ll be able to tick off your list immediately: Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882), the bearded guy astride a horse depicted in the marble statue outside the town hall.

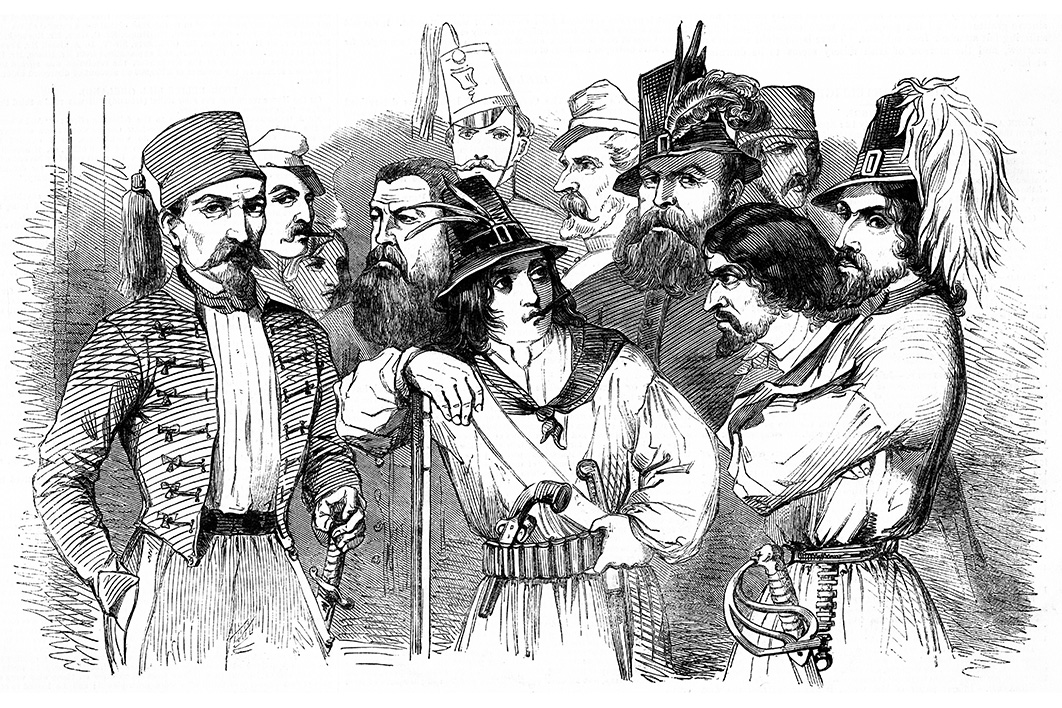

If there’s one founding father who has become synonymous with the Italian Revolution it’s Garibaldi. He’s the adventurer, the swashbuckling soldier, the strategic genius who honed his craft helping the oppressed in South America to claim their God-given right to nationhood. He was the fixer of Italian unity — the pragmatist who made it all happen while others were politicking or philosophising.

Garibaldi’s landing in the Sicilian port of Marsala in May 1860 with more than 1000 volunteers is the piece of history most Italians can remember from school; La Spedizione dei mille, the Expedition of the Thousand, is modern Italy’s First Fleet. It was during the battle of Calatafimi, in Sicily, that Garibaldi was said to have dropped the quote that would guarantee him a place in the Risorgimento’s pantheon: “Here we either make Italy, or we die.” He could have left it there and we’d still know his name. But he kept going, crossing the Strait of Messina and weaving his way up the mainland, fighting battles against the troops of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and cutting short the reign of the last Bourbon king of Naples, Francis II.

The rest is Italian history. The combination of the battles fought and won by the Thousand and local pro-Italian uprisings eventually created the modern Italian state, with the Piedmontese king, Victor Emmanuel, installed as the not-so-new monarch and Cavour as prime minister (he would die of malaria just months into the job). Mazzini remained in exile but eventually made it home, living in secret and later succumbing to illness.

Garibaldi’s reputation, meanwhile — both in Italy and abroad — continued to grow. His endorsement of the Union side of the American civil war prompted some to suggest he would be prepared to join that fight, although that never eventuated; the British named the garibaldi biscuit after him (Australian readers may know it as Arnott’s “Full O’ Fruit”); in Italy, the adjective garibaldino is used to describe courageous undertakings carried out with youthful enthusiasm.

I should confess that I have a personal link to Garibaldi-mania. My Scottish-born great-great-grandfather, William Millie Pie, once met Garibaldi in circumstances that remain vague. Captain Pie may have disembarked in a South American port, en route to Australia, at around the time Garibaldi was fighting with the Riograndense Republic as it attempted to secede from what was then the Empire of Brazil. Or they may have met when Garibaldi passed through Bass Strait sometime around 1852.

Whatever the circumstances, it was such a memorable meeting (for my ancestor, at least) that years later, after settling in Hobart, he christened his son (my great-grandfather) Arthur Savoi Garibaldi Pie — the second name a paradoxical reference to the Savoy royal family, the Italian dynasty that Garibaldi, an ardent republican, could barely tolerate.

As for the Risorgimento itself — well, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better foundation myth. A peninsula that for centuries had been divvied up by mercenaries and foreign powers — the French, the Austrians, the Spanish — took control of its fate and created a state, united (in theory) by a common language and culture. To do this, regions and cities that had spent hundreds of years fighting one another agreed to bury the hatchet in the name of a broader ideal of nationhood.

Ancient animosities among city-states remained deeply ingrained, of course — the expression “better a dead person in your home than a Pisan at your door” remains common currency in all Tuscan cities (except Pisa). But all of that was set aside in the name of the homeland. The secret revolutionary society that had first put the project on the map, the Carbonari, wrote the first chapter of an official history that culminates in the 1860 unification of Italy.

Given the country’s current and past political divisions, exacerbated by two world wars, it’s not surprising that Italy’s official mythology should attract some scrutiny. I know it has because I was introduced to the Risorgimento in the early 1980s in my last year of Italian middle school and our lessons were accompanied by much eye-rolling from our openly communist teacher. She viewed the whole thing with profound scepticism, suggesting that the push for national unification had merely been a pantomime staged by the Piedmont-based Kingdom of Sardinia to justify its colonial expansion.

My teacher also derided the suggestion that the push for statehood could have been driven by Italian patriotism — a sentiment so tarnished by the twenty years of Fascist rule between 1922 and 1943 as to have become socially unacceptable. On this, she had a point: modern-day Italians are happy to express patriotic fervour for achievements on the soccer pitch; they are far more cynical when it comes time to file a tax return.

Our professoressa brought the same far-left critique to bear on the founding fathers of the Italian state. Cavour was a lapdog of the establishment; Mazzini’s intellect was overrated; Garibaldi’s revolutionary zeal may have been admirable, but it was undermined by his preparedness to deal with those in power and his long-term membership of a masonic lodge. Our teacher even questioned whether there was anything worth celebrating in the creation of a nation. What’s the point of securing national borders if the pre-unity establishment remains in power? Transnational class conflict rather than national sovereignty was the lens through which many Italians made sense of the world in the 1980s.

The texts we used to decipher the Italian Revolution were also designed to challenge old assumptions. The opening scenes of The Leopard, by Sicilian writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, are set against the backdrop of Garibaldi’s red shirts sweeping through Palermo; the rest of the novel hammers home the message that a shift in power from Naples to Turin will change little or nothing. It’s an almost postmodern vision of Italian unity: patriotism is for naive idealists and opportunist spivs who want to believe that the new country is a break from the past, rather than a new disguise for old, entrenched centres of power.

It’s against this backdrop that British author Tim Parks has written his account of one of Garibaldi’s lesser-known undertakings: his 1849 escape, along with 4000 volunteers, from Rome to Ravenna, on the Adriatic coast. The Hero’s Way follows the logistical nightmare of the evacuation after a failed attempt to defend the shortlived Roman Republic from the siege of the French, who managed to have the Pope reinstated.

The daring operation was stamped with a trademark Garibaldi zinger — “wherever we will be, Rome will be” — and saw the Italians and their multinational group of supporters make their way up the peninsula, pursued by the French, Austrians, Spanish and Neapolitans. It meant that what’s now referred to as the first Italian war of independence ended not in defeat but in a public relations coup for Garibaldi.

If you need someone to explain Italy to you, you can’t do better than Parks. His accounts of life in the northern Italian city of Verona — Italian Neighbours and An Italian Education — demonstrate the type of insight that a foreigner can only glean through a deep understanding of both the culture and the language of the place. This has sadly become a necessary qualification, given the unstoppable expansion of the villa-in-Tuscany genre: those books by people who are parachuted into the country seemingly with the sole objective of complaining about local tradesmen.

Parks has always been the real deal — someone who has grappled with different and occasionally bizarre traditions and tried to make sense of them. Anyone can point to Italian mothers’ inexplicable fear of allowing their children to sweat or be exposed to air conditioning — but what does it mean? What can we learn about Italy through the idiosyncrasies of its people?

On this occasion, though, Parks delivers something different: a history-travelogue. Accompanied by his partner Eleonora, he puts on his rucksack and attempts to follow the escape route taken by Garibaldi and his men — along with their weapons and supplies — through often challenging Italian countryside. The history of the heroic trek north is interspersed with asides about the towns that Garibaldi would have visited, with reflections on how they are today.

On paper, this should tick all my boxes. The history is described vividly, with the vicissitudes of Garibaldi’s itinerary brought to life by the diary entries of Gustav von Hoffstetter, a Bavarian volunteer who had fought with the Republican army and ended up on the long march north. Parks’s fascination with Garibaldi is both justifiable and justified — like all of us who have invested time and emotional energy in understanding the country and its people, he’s on the lookout for a hero who can break free of Italian archetypes.

At their worst, Italians are inward-looking, intellectually lazy, unadventurous and uninspiring; at their best, they’re garibaldini: international, courageous and idealistic. By steering clear of the heroic deeds of the Thousand and homing in on a relatively unknown chapter of Garibaldi’s biography, Parks gives us a chance to see the man in a new light and to focus on the qualities that made him the world-famous leader we know today.

Yet the in-built travel diary is a hard slog. Admittedly, I’m not the target demographic — the reader who sees every small town in Italy as inherently quaint and picturesque may get more out of it. If I had a few months to kill in Italy, I’d sooner hang around Palermo, Florence or Bologna than engage in a historical re-enactment through the provinces.

That said, Parks gives us everything we could want from an Italian travel guide: the eccentric manager of the pensione, the morning cafe pit stop for a croissant and coffee, the southern Italian cedrata that’s just the drink you need at the end of a big day. But the rapid and repeated transition between 2019 and 1849 can at times be jarring.

“We have light trekking shorts… while the garibaldini wore grey woollen trousers with a red stripe,” Parks tells us at one point. “And we’ve discovered elasticated anti-rash athlete’s underwear, for which I am immensely grateful. What wonderful progress has been made in fabrics over the last two centuries! Did Garibaldi’s men even have underwear? I fear not.” These asides made me wish that Parks had stuck to the history of the freedom march, which is, after all, the most riveting yarn a writer could hope for.

By the time Garibaldi made it to the city-state of San Marino, not far from the Adriatic coast, his men were shoeless and bedraggled, close to the end. Anita, Garibaldi’s Brazilian wife who was by then pregnant and exhausted, lashed out at the soldiers as they did a runner for the San Marino border, under fire from the Austrians. San Marino offered them refuge, but it became clear that Garibaldi was heading for a showdown that he couldn’t win. The Austrians demanded unconditional surrender and Garibaldi wasn’t about to offer it.

That’s the cliffhanger Parks leaves us with as he walks us through an exhibition of relics of the freedom march in the modern-day Republic of San Marino: Garibaldi’s saddle; his pistol; a camp fork and spoon; a banner of the First Roman Legion.

Negotiations led nowhere because Garibaldi found the terms of surrender too humiliating — not necessarily for his men, but for himself. Having written a sharp note declining the offer, he told his inner circle that he had no choice but to decamp, having already disbanded his army, in the hope that he could make it to Venice, where the fight against the Austrians continued. Anita was encouraged to stay in San Marino but remained steadfast in her resolve to remain by his side. She would die, in Garibaldi’s arms, in an ill-fated attempt to reach Venice by boat.

His decision to skedaddle from San Marino in the night, without informing his men, was a telling moment. Garibaldi may well have believed that the best way to ensure the soldiers were treated fairly by the Austrians was to ditch them — Parks and Eleonora weigh up that very question while visiting the city-state. He was the man foreign powers wanted to stop; the handful of followers weren’t the prize. Yet there was something unbecoming about his relationship with his men.

In Parks’s writing, Garibaldi comes across as aloof, although self-aware enough to know that if Italy was to be unified then he was the one person who stood a chance of doing it. The Garibaldi in the history books is a leader of men; in this examination of his march to freedom, he appears as a strategic thinker whose loyalty was directed at his own destiny. He knew that he needed to make it out of this situation in one piece, and everything he did appears to have hinged on that objective.

Garibaldi never made it to Venice. In fact, he was lucky to make it back to Piedmont alive, after being smuggled through the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and boarding a boat back to the Ligurian coast. He was arrested upon his return, only to be freed again after a parliamentary debate in Turin. His biggest adventures still lay before him: his journey around the world as a trader, his nine months in New York working in a candle factory and, of course, his triumphs on the battlefields of Southern Italy.

Yet his drive to succeed was already clear on the freedom march north, his reputation enhanced by every town he visited along the way. His campaign was as political as it was military; he was winning hearts and minds. Parks quotes a plaque in Terni, the Umbrian town where the escaping soldiers arrived, unclear about the direction they needed to take to reach safety:

In July 1849

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Venice-bound

refreshed here…

The citizens and the town council

marked with reverence

the great commander’s footprint.

That’s a personal legacy that no Risorgimento revisionism will ever take away. •