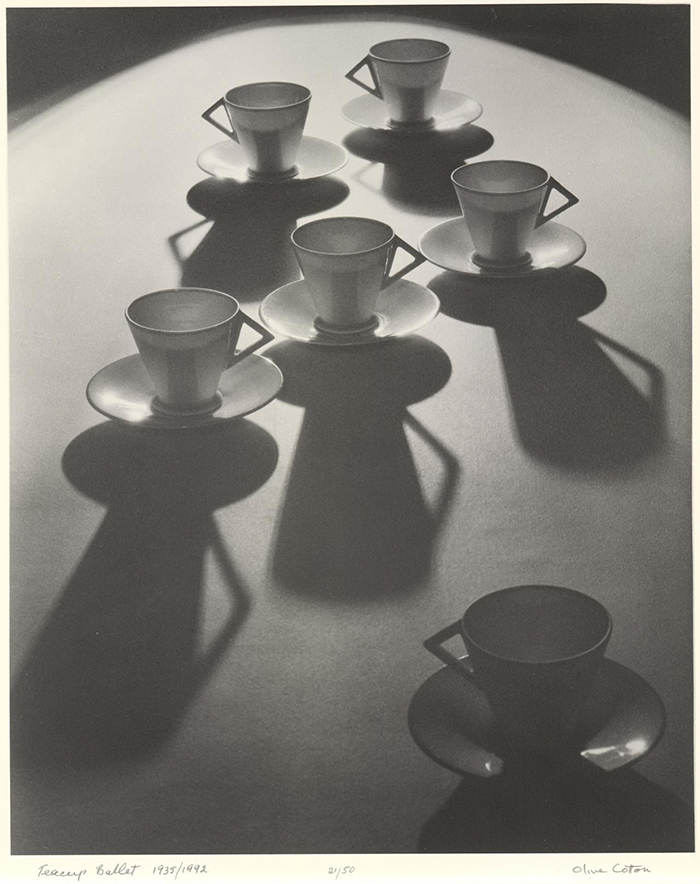

Of all the works of the Australian photographer Olive Cotton, Teacup Ballet (below) is the best known. Made in 1935, when Cotton was only twenty-four, this remarkable image taps into currents of modernism, both national and international, that Cotton seems to have recognised and absorbed almost instinctively. It shows inanimate objects, half a dozen cups in their saucers, in a configuration that by means of careful placement and sophisticated use of light and shadow conveys a strong sense of theatrical performance, of objects brought to choreographed life. Everything about it speaks of deliberation and control, yet the overall effect is of a kind of geometric vitality.

As Helen Ennis makes clear in her absorbing new biography, Olive Cotton: A Life in Photography, a lot went into getting everything just right in Teacup Ballet. Ennis provides an illuminating insight into a version that Cotton rejected, in which the arrangement of the cups and saucers, more precise and regimented, failed to suggest interaction in the way the final, almost but not quite symmetrical version so triumphantly does.

With their angular handles and clean lines, these teacups are very much of their period, loudly proclaiming their modernity. At the same time they speak of more traditional, unrevolutionary pursuits, of afternoon tea in lengthening shadows and of someone taking the trouble to lay everything out just so. In one of a number of suggestive asides that gently hint at the influences on Cotton’s artistic development, Ennis notes that Olive’s mother was fond of china painting. It is recorded, for instance, that she “decorated a set of sweet dishes with images of flannel flowers.” The strength of Teacup Ballet lies in how it combines something of this sense of domestic order and civilised pursuits with a more adventurous meditation on the relationship between animate and inanimate, traditional and modern.

Geometric vitality: Olive Cotton’s Teacup Ballet (1935). National Gallery of Victoria

Cotton was to live for almost seventy years beyond Teacup Ballet. During that time she achieved early success both artistically and commercially, first in the company of husband and business partner Max Dupain and then very much on her own account. Separation and divorce from Dupain, followed by her marriage to Ross McInerney, brought a sharp change in direction, and decades raising a family under often difficult conditions meant that there was little time for photography. Only later in life did Cotton re-enter the commercial world by opening a photographic studio in the central west NSW town of Cowra. There she produced wedding and graduation portraits for the local community while tentatively seeking again the kind of wider recognition that she had briefly enjoyed many years earlier.

Although Cotton established herself independently during the war, attracting some important commissions, it was only in later life that she began to be redefined as one of the crucial pioneers of modern photography in Australia in her own right, rather than primarily in the context of her formative relationship with Dupain. Interest in the history of photography had grown, and neglected female artists were receiving overdue recognition. When that second wave of recognition came, as it did with a flurry in the 1980s, it was not so much for her recent work, then hardly seen outside the reach of her own domestic circle and her local client list, but for the images dating from the 1930s and 40s, the period when Cotton’s technical mastery and artistic range grew with remarkable speed.

Cotton always acknowledged the importance, in professional terms, of her early relationship with Dupain. Family connections combined with a shared enthusiasm for photography and the natural world drew them together from an early age. The careers of professional photographers can often be traced back to the chance gift of a camera, or of the means to buy one. In Cotton’s case it was a present from an aunt, while Dupain in his mid-teens bought a Kodak Folding Brownie with money given to him by his great-grandmother. They had both demonstrated an early artistic talent but, judging their own skills harshly (Cotton felt that any ability she may have had in drawing was far outmatched by her sister’s), they were irresistibly attracted to this newer artistic medium.

As they grew closer and spent more and more time together during their adolescent years, Olive and Max must have struck all who knew them as, to use the old phrase, made for each other. Ennis allows for the possibility that they began themselves to feel that the story of their lives had already been written, and that they were being carried along with it. Indeed in another universe we might now be reading their joint biography, the tale of a couple united by love and a shared talent who built successful and mutually reinforcing careers. But that is not the way it turned out.

Max Dupain consciously embarked on a career in photography even before leaving school, taking advantage of the opportunities for experience and advancement available to him as a man. Olive quietly absorbed his knowledge and kept pace with him in their increasingly sophisticated understanding of the capacities of the medium. But while Dupain was fast-tracking himself as a professional photographer, Cotton studied English and mathematics at the University of Sydney, reflecting “her family’s dual interests in science and the arts”; it was a fitting duality, as it transpired, for a career in photography.

The mathematics stood her in good stead: in later years, under financial pressure, she took a job teaching maths at Cowra High, where she was regarded as a gifted teacher right up until when, lacking a qualification in education, she was forced out by the rise of credentialism. At university she had also taken a course in anthropology, which was not a success: “I was too prim and proper for anthropology,” she recalled. “You had to talk about all sorts of things and I couldn’t bring myself to do it.” By her own account, she had “dodged the big questions, the things I didn’t feel I could talk about comfortably.”

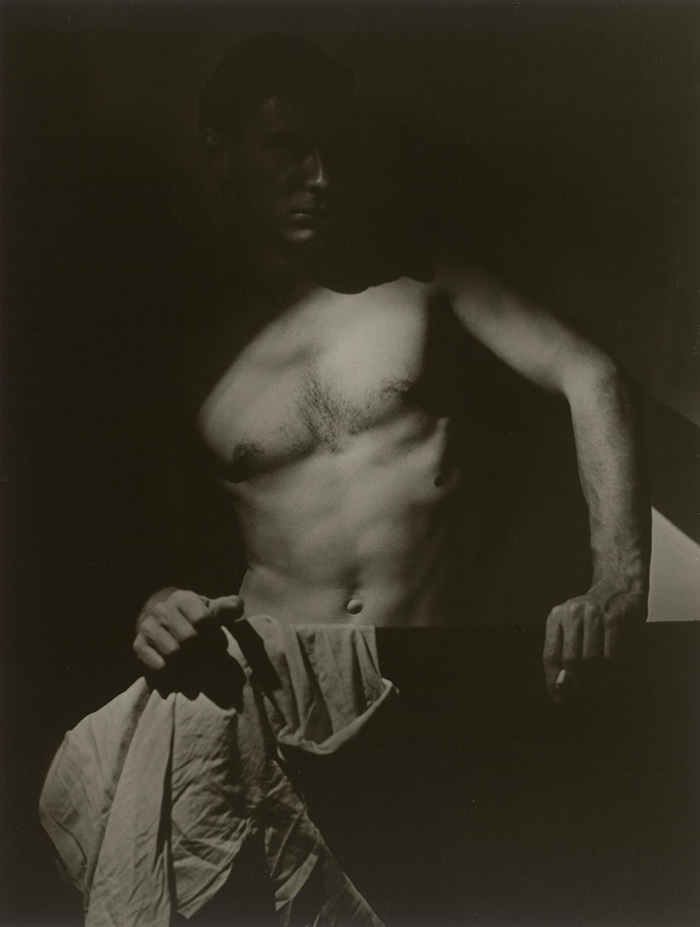

This delicate allusion to her own youthful unworldliness contrasts strikingly with the freedom Cotton felt only a few years later to tackle such matters visually. Her photograph of Dupain, Max after Surfing, dates from 1939, the year of their marriage. It shows Dupain as handsome and, despite the cigarette in one hand, impressively fit-looking (his mother fed him celery biscuits, Ennis tells us, in one of many examples of her eye for the fascinating detail). Notwithstanding Cotton’s reticence in anthropology seminars, the image conveys a striking and unembarrassed eroticism. The subject poses, but it is a low-key, undemonstrative performance. The result is both subtle and frank — an extraordinarily difficult combination to achieve.

Subtle and frank: Olive Cotton’s Max after Surfing (1939). National Gallery of Victoria

But against the power of the photograph is the strong likelihood that their relationship was already beginning to disintegrate. Ennis deals sensitively with the reasons for the breakdown, acknowledging how little is known for certain and how much has to be inferred. A later, glancing comment by Olive, made in an interview in 1983, is allowed to bear much of the weight. “You grow up together,” she remarked, as “good friends. But marriage doesn’t work.” By 1941 Olive had acted on this conclusion and taken her leave.

There are many aspects of Olive Cotton’s life that we cannot really know, about her attitudes and priorities and what really lay behind her determination to pursue photography regardless of the many obstacles. “As a biographical subject… Cotton has surprisingly little weight,” Ennis says, in the first of several such references. A friend describes Cotton as by nature a “background figure,” and Ennis herself echoes this description, calling her a “distant figure.”

Her second husband, Ross McInerney, was to claim, rather implausibly, that he “never heard her speak ill of anyone, not once.” While it is clear that she was liked and loved and admired by those who knew her, there is the sense that even those closest to her detected something unknowable. She retained the manner of an observer, rather than a central participant, an essential quality perhaps for any successful photographer.

As biographer, Ennis must deal not only with the elusiveness of Cotton herself but also with the larger-than-life personalities of the men she married. It is a balancing act to give these two talkative and often charming men their place in the story while keeping Cotton very much in the frame, ever alert to the danger that she will slip into the background. One of the fundamental strengths of Ennis as biographer is that she achieves this difficult balance, giving both men their due and never rushing to simple judgement, while at the same time ensuring that the main light falls consistently on her central subject. As she reminds both herself and the reader at one point, “this is Olive’s story.”

Olive Cotton “did not travel far during her ninety-two years.” She never went abroad, or indeed ventured beyond the eastern states of Australia, essentially confining herself for the most part to Sydney and the central west of New South Wales. This apparent preference for staying close to home would have been driven, as it was for many of her generation, by circumstance as much as choice and doesn’t necessarily reflect a lack of desire or interest. In fact, within these geographical constraints, Cotton was by nature a roamer who loved the beach and the bush and who never tired of exploring familiar ground, alert always to the possibility of coming across something previously unnoticed, or noticed anew in a different light.

For most of their long marriage, which lasted from 1945 until her death in 2003, Cotton and McInerney lived on land at Spring Forest, outside Cowra, initially in a simple two-bedroom weatherboard cottage, and later in an adapted construction workers’ barracks that still stands, preserved by the family. Ennis notes, with pointed restraint, that “on some of the bedroom doors” of this “new” house, “small Dymo labels are attached” bearing the names of some of the previous occupants who had been workers on the construction of a dam at nearby Carcoar.

Ennis can’t quite conceal her surprise at the fact that Olive and Ross, despite occupying the house for decades, never once took a moment to remove the labels, even though they could have torn them off in an instant. Whether this was deliberate on their part, as Ennis implies, or merely a decades-long oversight is impossible to say. Whatever the explanation, it suggests a shared reluctance to tamper unnecessarily, and a preference for leaving things as they are.

Olive Cotton as stay-at-home, as the kind of person who would leave other people’s names on the doors of her own home for decades — who would put up with a wobbly step or a leaking roof for year after year — suggests a photographer who would favour framing and recording and preserving, but otherwise leaving the subject to speak for itself. But while for the most part Cotton avoided what might be termed technical interference with her images, they are often nevertheless highly organised, considered, arranged and complex in their apparent simplicity. She could return repeatedly to the same vantage point and wait patiently until the light she was looking for was just right. When it came to photography, as distinct from houses, she was not necessarily one to take things as she found them.

Photography for Cotton consisted of the entire process, from set-up to darkroom. In the years when she was trying to maintain her commitment to her art against the demands of domestic life, it was particularly frustrating to take a photograph and then to have to defer the development and printing of the final image until she had the time and the means and the necessary access to equipment. The taking and the making of the image were inseparable. “I like to do everything myself from start to finish,” she later explained.

If a long life spent together is an indication, Cotton’s second marriage was a success. As with many long-lasting marriages, it was never quite clear to outsiders why that should have been so. Olive and Max had seemed made for each other, Olive and Ross less so. He made too many cups of tea, his sister recalled, a sharp but not unsympathetic comment that calls up an entire postwar world, of men who returned from active service knocked sideways by the experience, who could never quite settle to anything afterwards, who began tasks with enthusiasm and stopped halfway through, who had moods and could, as the saying went, be difficult to live with.

Ross was concerned that by marrying him and moving to the country Olive would have to give up too much, “just when you have made a name for yourself.” Olive McInerney did indeed give up her name, and in more ways than one, but there is no real evidence that she felt the price of marriage and family was too high. Despite occasional storms, she remained devoted to Ross and their children, but the price was real. After 1946, when Olive and Ross moved as a married couple to the country, Ennis notes starkly, “little of Olive Cotton’s photography would appear in public, in either publication or exhibitions, for the next three decades.”

The key phrase here is “in public.” It might have been tempting to see Cotton’s career in terms of an early and a late period, punctuated by a long interregnum in which she concentrated on other things. That may be true as far as it goes, but Olive Cotton: A Life in Photography shows that beneath the surface Cotton never really wavered; it was indeed a life in photography. During her long period of isolation from the world of magazines and commissions and of contact with fellow practitioners, Cotton adapted to the circumstances, turning her photographic eye towards her own family and her immediate surroundings, which meant that when she did open her studio in Cowra she was far from being out of practice.

Towards the end of her life, when she was in her mid-eighties, Cotton created an image that shows how her fundamental preoccupations — with the effects of light and shade, with the interactions of elements within the frame, and with how pattern and a strong sense of composition can also suggest vitality and movement — never really changed. Unlike Teacup Ballet and Max after Surfing, no such vitality or movement is implied in the title of this late image. It is called simply Moths on the Windowpane. There are dozens of them, captured as they cling to the window, attracted by the light inside. Ennis convincingly places this image of these short-lived creatures in the context of Cotton’s approaching death. The light will go out and the moths will move on, but for the moment they are fixed, in a mutually reinforcing pattern that recalls those early teacups.

Near the end of this illuminating and moving account, we visit Olive Cotton’s graveside. If you are looking for Cotton here, says Ennis, you will not find her. The name on the marker instead reads “O. McINERNEY,” a subtle echo, which Ennis does not labour, of those Dymo labels on the barracks doors. It is unlikely, however, that Olive Cotton would have been unduly bothered by this brief form of identification, even with her professional last name overwritten and her first reduced to an initial. At the end of her life she could balance this version of herself with her ever-rising reputation as Olive Cotton, no longer in the background but now a figure at the forefront of Australian photography, the determined artist who, when she resumed her professional life in Cowra, had arranged for a replica of her signature, “Olive Cotton,” to be painted in bold above the entrance to her new studio. •

Olive Cotton: A Life in Photography

By Helen Ennis | HarperCollins | $49.99 | 544 pages