How vulnerable is the Chinese economy — and hence, China’s leaders? Very, says Peter Zeihan, a geopolitical analyst whose CV includes a US State Department posting in Australia.

In a recent article, Zeihan contends that China’s recent “spasming belligerency” — its “torching” of its diplomatic relationships — is a sign “not of confidence and strength” but rather of “insecurity and weakness”; that its leadership knows “full well” that China’s growth model is “unsustainable” and “past its use-by date”; and that “everyone in the top ranks of the Chinese Communist Party” knows that “the day is coming” when “China’s entire economic structure and strategic position crumbles.”

Zeihan is hardly the first person to say these sorts of things — William Overholt made similar points in Inside Story earlier this year — and I suspect he won’t be the last person to be wrong about them, at least in the near term.

That’s not to say that his article doesn’t draw on undisputable facts. There’s no denying that China has been extraordinarily profligate in its use of capital, and has become progressively more so over the last two decades. Paul Krugman famously made the same point in 1994 about the smaller East Asian economies, which were growing rapidly a few years before the Asian financial crisis; his article, “The Myth of Asia’s Miracle,” was wrong in some important respects but is still worth a read if you ask yourself whether what he said about the “Asian tigers” back then applies to China today.

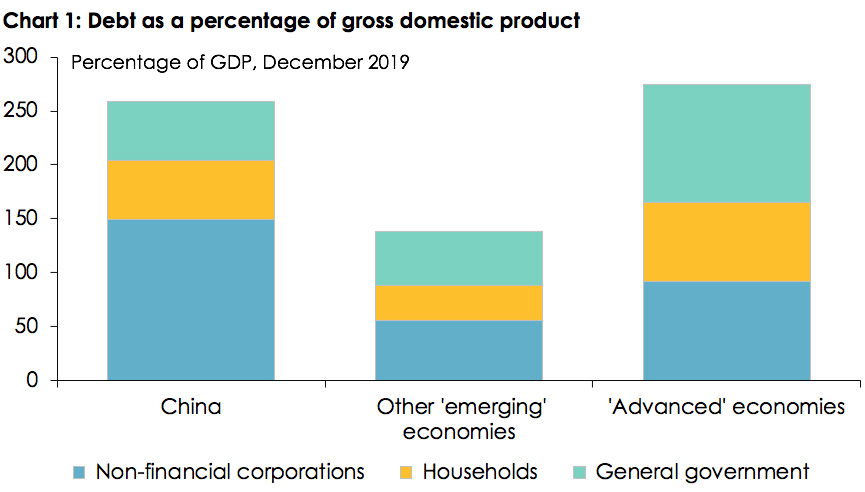

Nor is there any denying that China has an enormous amount of debt (relative to its GDP), especially for what is still in many ways a developing economy.

Source: Bank for International Settlements, Credit to the Non-Financial Sector, June 2020.

But — and this is an important “but” — most of that debt is owed by state-owned enterprises to state-owned banks, and can be thought of as two entries on opposing sides of the same balance sheet, that of the People’s Republic of China. If a lot of that debt were to turn bad, which is by no means impossible, then the ensuing crisis could be solved by writing it off and then recapitalising the state-owned banks by drawing down on the foreign exchange reserves of the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank.

In fact, China has done this twice before, in the late 1990s as part of the state-owned enterprise reforms pushed through by then-premier Zhu Rongji, and again between 2003 and 2005, when the big four state-owned banks were cleaned up ahead of their (very) partial privatisation and listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. The banks’ bad assets were transferred into an entity called Central Huijin, which became the nucleus of China’s sovereign wealth fund, the CIC.

What we don’t know is whether the People’s Bank’s foreign exchange reserves would be sufficient for what could be a much larger task this time round. The People’s Bank lost a quarter of its reserves (almost US$1 trillion) defending China’s currency, the renminbi, between June 2014 and December 2016 — after which it imposed the very strict controls on capital outflows that have remained in force ever since then. These controls are more easily maintained by an authoritarian regime that knows how to deploy modern technology for surveillance purposes than by other governments, such as Argentina’s, that have also tried to use them.

Since the end of 2016, the ubiquitous “Chinese authorities,” as they’re always referred to by Western economists, have been acutely aware of the risks to financial stability posed by the growth of “shadow banks” and their opaque “wealth management products.” They also know that Chinese banks have become more dependent on wholesale funding and less on deposits by account-holders for the liabilities side of their balance sheets — just as US and European banks did, to a much greater extent, in the years leading up to the global financial crisis.

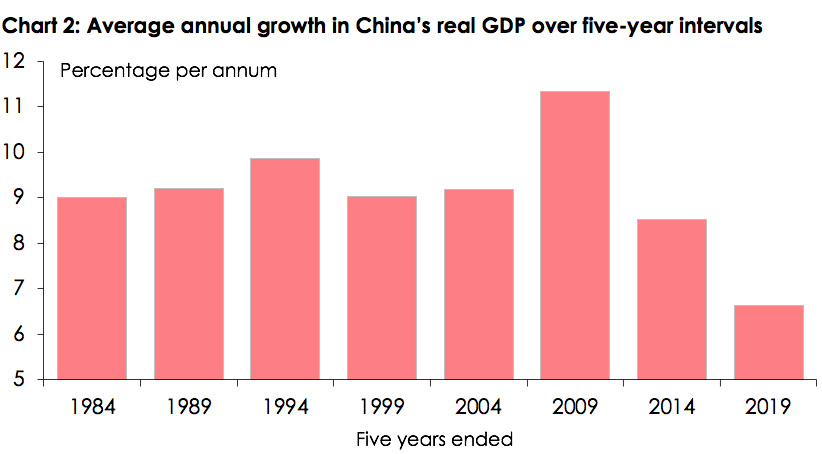

That’s partly why China’s growth rate has been steadily slowing over the course of the past decade, from an average of 11.3 per cent in the five years to 2009, to 8.5 per cent in the five years to 2014 and 6.6 per cent in the five years to 2019 (see Chart 2). Another important reason, of course, is that China’s working-age population peaked in 2014 and has since shrunk by almost 1.5 per cent.

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics.

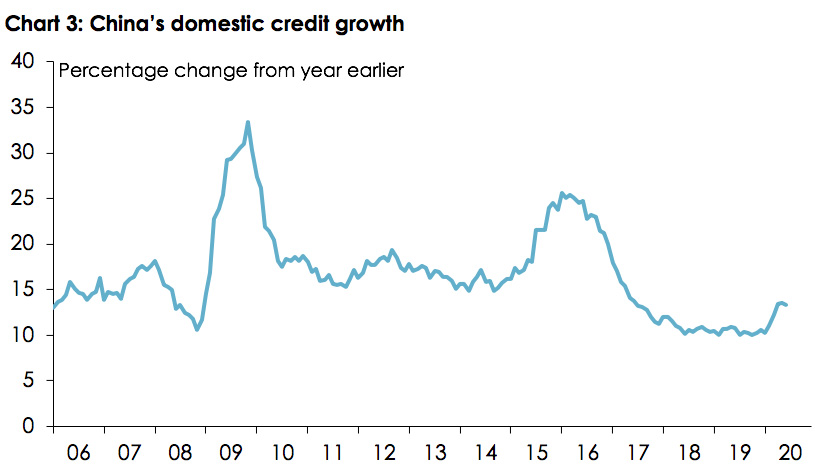

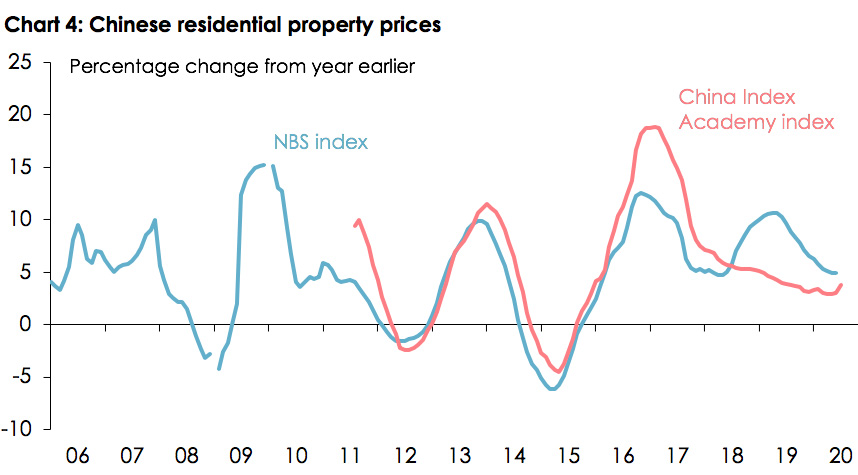

It also helps explain why the People’s Bank hasn’t done nearly as much monetary stimulus as it did during and after the global financial crisis or in 2015–16. Credit growth has not accelerated significantly in recent months (Chart 3), and nor has there been a surge in property development activity or property prices, as there would have been if the People’s Bank had unleashed another spurt of credit growth (Chart 4).

Source: People’s Bank of China, Depository Corporations Survey, June 1990.

Sources: China National Bureau of Statistics; China Index Academy.

The Chinese authorities do seem to be doing more fiscal stimulus than they did twelve years ago, although it is taking a very different form from the construction-intensive programs that they implemented then.

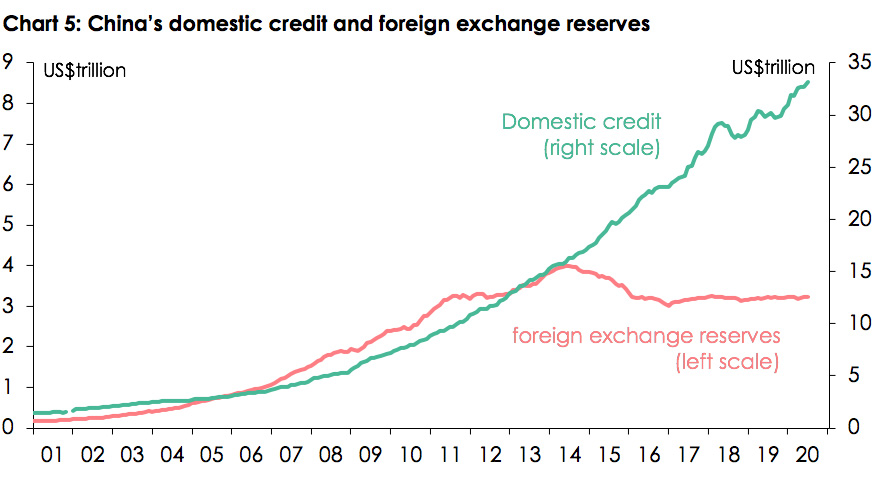

As economist Jonathan Anderson has shown, the most worrying potential development — albeit not during the next year or so — is the one depicted in Chart 5, which shows a marked divergence between the level of foreign exchange reserves and the rate of growth in domestic credit since the mini-crisis of 2015–16.

Note: Domestic credit converted from yuan to US dollars using month-average market exchange rates. Sources: People’s Bank of China; Jonathan Anderson (2020); author’s calculations.

For a fixed exchange rate system to be sustainable, foreign reserves and domestic credit ordinarily need to maintain a fairly close and stable relationship, which they do under a “currency board” system like the one Hong Kong has had since 1984 (or that the Baltic states had before joining the euro, or that Bulgaria still has). In such a system the monetary authority is explicitly precluded from issuing currency unless it is backed by foreign reserves (or, in Hong Kong’s case, foreign reserves plus the Land Fund).

That’s why the collapse of fixed exchange rate regimes (such as Thailand’s in 1997, or Argentina’s in 2001) is usually precipitated by a surge in capital outflows, and a sharp decline in foreign reserves.

China’s foreign exchange regime is no longer completely fixed, of course; it is carefully managed around a peg to a trade-weighted index (as the Australian dollar was between 1976 and the currency float in 1983). But the People’s Bank’s capacity to maintain that peg is dependent on the credibility of its implicit promise to buy or sell renminbi in whatever quantity is required to keep the currency close to the peg.

Obviously it can sell the renminbi in whatever quantities it likes. The People’s Bank is its ultimate source, and that means it can always prevent the currency from appreciating too much (as can any country prepared to accept the potentially inflationary consequences of a sudden large increase in the domestic money supply).

But the Chinese don’t own or operate a US dollar factory, so they can only prevent a big depreciation (if one were to be in the offing) for as long as they have sufficient foreign reserves to satisfy everyone who wants to convert renminbi into dollars (or some other foreign currency). That’s why capital controls are so important at the moment: because they limit the demand for foreign currencies, meaning that the level of foreign reserves is more than adequate, and widely regarded as such.

If some occurrence caused a tsunami of capital outflows and the Chinese authorities didn’t have any other ways of stopping it (such as confiscating the assets of, or imprisoning or executing, people who tried to get their money out of the country, something I’m sure they wouldn’t baulk at), then there would be a currency crisis; the renminbi would fall a lot; and the weakness in the domestic financial system (resulting from the accumulation of so much bad debt) would be fully exposed.

But how likely is that to happen in the foreseeable future? I can’t really see any reason to answer that question with anything other than “not very.”

It’s worth remembering that the lesson the Chinese Communist Party drew from the collapse of the Soviet empire is that once brutal authoritarian regimes have clearly failed to deliver ongoing improvements in people’s well-being, which they promise in return for the surrender of individual freedoms, they can only survive as long as they are willing to kill their own people in sufficient numbers pour encourager les autres, or someone else is willing and able to do it for them.

Thus the communist regimes of Eastern Europe, most of which had been demonstrably willing to shoot their own people (or allow the Soviets to do it for them) at various times in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1980s, collapsed when they lost the will to shoot their own people, and the Soviets under Gorbachev lost the will to do it for them.

And the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991 when neither Gorbachev, nor the cabal of drunken fools who briefly tried to overthrow him in August of that year, were willing to shoot their own people.

It’s worth noting in passing that Vladimir Putin has repeatedly demonstrated that he has no such scruples about killing his own people — whether they are ordinary Russians in high-rise apartments around Moscow, middle-class Muscovites attending the theatre, schoolchildren and their parents in Beslan, troublesome journalists, former KGB agents living in the UK, lawyers for aggrieved hedge fund managers, or prominent opposition figures.

By contrast with their contemporaries in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng demonstrated that they were perfectly relaxed about the idea of killing large numbers of their own people in order to ensure that they remained in power — and even better than Josef Stalin at airbrushing those events out of the collective memory. And I suspect nothing has changed, at least in that regard, since then.

Indeed Xi Jinping has repeatedly shown that he’s prepared to do whatever is required to entrench the party as the source of all power in China, to sideline potential rivals and to remain in office for as long as he is capable of drawing breath (not least because he’s smart enough to know that he’s made a lot of enemies, and that they would take their revenge on him and his family and supporters as soon as he was out of power – as Putin did to Boris Yeltsin’s wealthy supporters).

Far from feeling weak and insecure, I think China feels strong and emboldened — not only by its apparent success in stopping the spread of Covid-19, admittedly after a number of initial serious missteps, but also by the manifest incompetence of the US administration in dealing with the virus, and its almost complete abdication of its traditional global leadership role (something that, to be fair, didn’t start under Trump).

That’s why Xi has explicitly discarded Deng Xiaoping’s dictum that China should “hide your capacities and bide your time” — much as Woodrow Wilson and, more forcefully, Franklin D. Roosevelt and his successors all the way to George W. Bush were prepared to discard George Washington’s advice, in his 1796 farewell address (which was actually written by Alexander Hamilton) to “avoid foreign entanglements.”

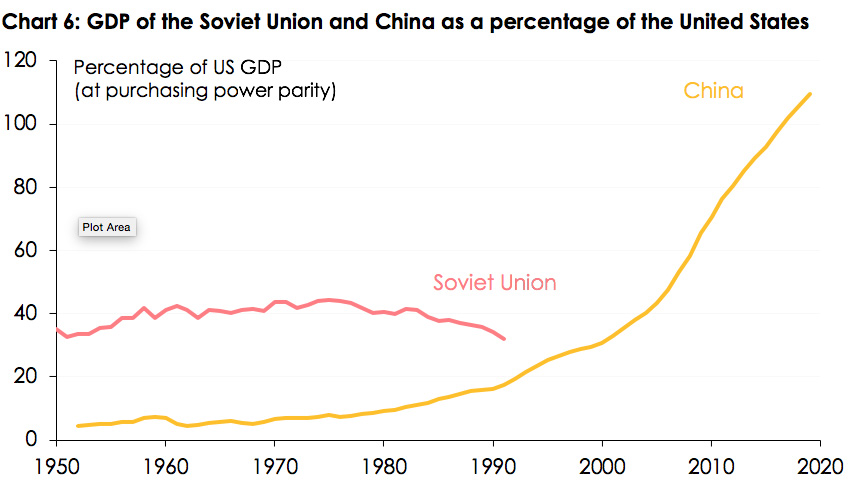

Xi (and, as far as one can tell, most of the Chinese population) think that now is China’s time — that’s what he means by phrases like “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” and “the Chinese dream.” And of course China’s economy, notwithstanding its burden of debt, is much stronger than the Soviet Union’s ever was.

Note: Comparison between the Soviet Union and the United States is based on estimates of GDP in 1990 US dollars at purchasing power parities, or PPPs; comparison between China and the US is based on official estimates of GDP in 2019 US dollars at PPPs. Sources: The Conference Board, Total Economy Database TM, September 2015 and July 2020; author’s calculations.

The closest the Soviet Union’s economy ever got to matching that of the United States was 44 per cent of US GDP between 1974 and 1976; by the time Gorbachev took office in 1985 it was down to 38 per cent, and in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, it was only 32 per cent.

By contrast, China’s economy — measured in US dollars converted at purchasing power parities — surpassed the United States’s in 2017, and this year is likely to be at least 10 per cent bigger. (Of course, measured in US dollars at current exchange rates rather than at “purchasing power parities,” the Chinese economy is still only about two-thirds of the size of the US economy, but that’s a lot closer than the Soviet Union ever got.)

It’s perhaps also worth noting, apropos of something that Peter Zeihan over-emphasises, that China isn’t really all that dependent on exports any more. In 2019, exports accounted for only 18.4 per cent of China’s GDP (according to World Bank data), down from a peak of 36 per cent in 2006, and less than in any year since 1991. Big economies, like China’s now is, tend to be relatively closed: thus, exports only represent 12 per cent of US GDP and 18.5 per cent of Japan’s (compared with Australia’s 24 per cent, for example).

So, to summarise, I don’t really agree with Zeihan’s proposition. Of course, in the long run (when, as Keynes famously wrote, we’re all dead), he may turn out to be right. But it’s not something I’m going to wake up any morning soon expecting to hear about. •