Barely six weeks ago, in mid August, I wrote optimistically about how US president Joe Biden was implementing the program he promised in his presidential bid — bold action on a broad range of domestic issues, a restoration of America’s international standing, and an effort to reduce the acrimony and obstructionism that has characterised Washington in recent years. Now he faces a series of political contretemps that could undo his presidency and severely damage his party’s chances in the 2022 midterm elections.

Nor are his problems caused exclusively by a unified and implacable Republican opposition; they’re also a result of bitter divisions and competing demands within his own party. Thanks to political stand-offs between Democratic factions, the two bills to implement Biden’s domestic policy agenda — the bipartisan infrastructure bill (so-called because it garnered some Republican votes when it was passed by the Senate in August) and the social policy measures of the US$3.5 trillion Build Back Better bill — are stalled in the House.

For several days last week, obstreperous congressional Republicans looked like bringing the United States to the brink of financial collapse and a government shutdown. The last day of September marked the end of the financial year in the United States and, with that, the expiry of funds for federal government activities. Failure to reauthorise funding would mean all the chaos and costs of a government shutdown.

On top of this, the debt ceiling — an entirely artificial limit on how much money the US government can borrow — will be reached within days. A failure to increase the government’s borrowing authority would see the United States defaulting on its debt for the first time in history, putting at risk some six million military and government jobs, and threatening social security and child tax benefit payments. As Treasury secretary Janet Yellen has warned, the consequences would be “a self-inflicted wound of enormous proportions,” with both national and international consequences.

Those twin threats — a debt default and a government shutdown — aren’t new, but now Mitch McConnell, Republican leader in the Senate, is doubling down on a Republican campaign to undermine Biden’s broader economic agenda.

Republicans have previously had no problems voting to raise the debt ceiling — indeed, more than a quarter of the country’s US$28.4 trillion federal debt was accumulated during the Trump presidency. But McConnell says no Republican will vote to raise the debt limit and the Democrats must shoulder the entire political burden of such a move. No principle is involved; this is pure politics.

Last Monday Senate Republicans blocked a bill already passed by the House that would fund the government until 3 December (by which time appropriations legislation for fiscal year 2022 would ideally be enacted). The bill would have provided billions of dollars in natural disaster relief and help for Afghan refugees, and would have avoided a default on the national debt. The Senate Republicans also blocked the Democrats’ procedural motion to allow a simple majority vote to raise the debt ceiling.

The brinkmanship partially collapsed on Thursday, probably because congressional leaders recognised that no politician or political party benefits from a government shutdown. The provision to raise the debt ceiling was stripped from the continuing resolution which then passed the Senate (65–35), having survived a Republican attempt to limit benefits for Afghan refugees. Back in the House, it was passed 254–175; then, just hours ahead of the shutdown deadline, it was signed by President Biden.

For the moment, the debt ceiling is a can that has been kicked a small way down the road; it’s calculated that it will be breached around 18 October. Failure to deal with it more comprehensively will cause a lot of pain and could trigger a recession and financial crisis. Already the financial markets are nervous.

Republicans are presumably looking to portray the Democrats as ineffective financial managers, but it’s a dangerous game. In the end, the debt ceiling must be, and will be, raised (even if none of Biden’s new policies are enacted).

It might also be a pointless game. In the midst of a pandemic, public concern about the budget deficit is down. Gallup polling shows Americans are less worried about the deficit than a decade ago (only 49 per cent worry about it “a great deal” in 2021, compared with 64 per cent in 2011). A recent Morning Consult/Politico poll found that a plurality of voters would hold both political parties equally responsible for a default, although more voters would assign blame to Democrats (31 per cent) than Republicans (20 per cent).

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, meanwhile, is being kept busy wrangling with her Democratic colleagues over how to proceed with both the infrastructure bill and the Build Back Better bill. She and her lieutenants have so far done an amazing job of shepherding the provisions and funding for the US$3.5 trillion Build Back Better package through thirteen House committees. The bill is proceeding under the budget reconciliation process, which means only a simple majority of votes is required in the Senate.

But it’s there in the Senate — where the Democrats can’t afford to lose a single vote — that two Democrat senators, Joe Manchin from West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema from Arizona, are holding out. The progressive Democratic caucus in the House, with nearly one hundred members, has vowed to defeat the infrastructure bill unless the Senate is certain to ensure passage of the Build Back Better bill. The progressives rightly fear that the scope of the bigger bill will inevitably be whittled down as Biden and the White House endlessly negotiate with Manchin and Sinema, and more moderate House Democrats push for action.

Both senators are pushing for a smaller package. But while Manchin has publicly outlined his concerns, Sinema has been far more enigmatic and has largely declined to make her fears public.

Manchin, a centrist Democrat from a Republican-leaning state relishing the power he is wielding, has said he could support a US$1.5 trillion package and indicated his willingness to negotiate. He insists that the legislation must also include the Hyde Amendment (a legislative provision barring the use of federal funds to pay for abortion). He seems to be running his own agenda here: Biden’s domestic spending proposals are immensely popular in the poor, coalmining state Manchin represents, even among those who voted for Trump.

Sinema, a first-term senator, might also be enjoying the spotlight. She too has baulked at the legislative price tag — and at some of Build Back Better’s tax-raising provisions — but she hasn’t been willing to discuss these concerns with the White House. Among Democrats in Arizona she is increasingly seen as an obstructionist; indeed, she was recently censored by the state party for her stance on the bill.

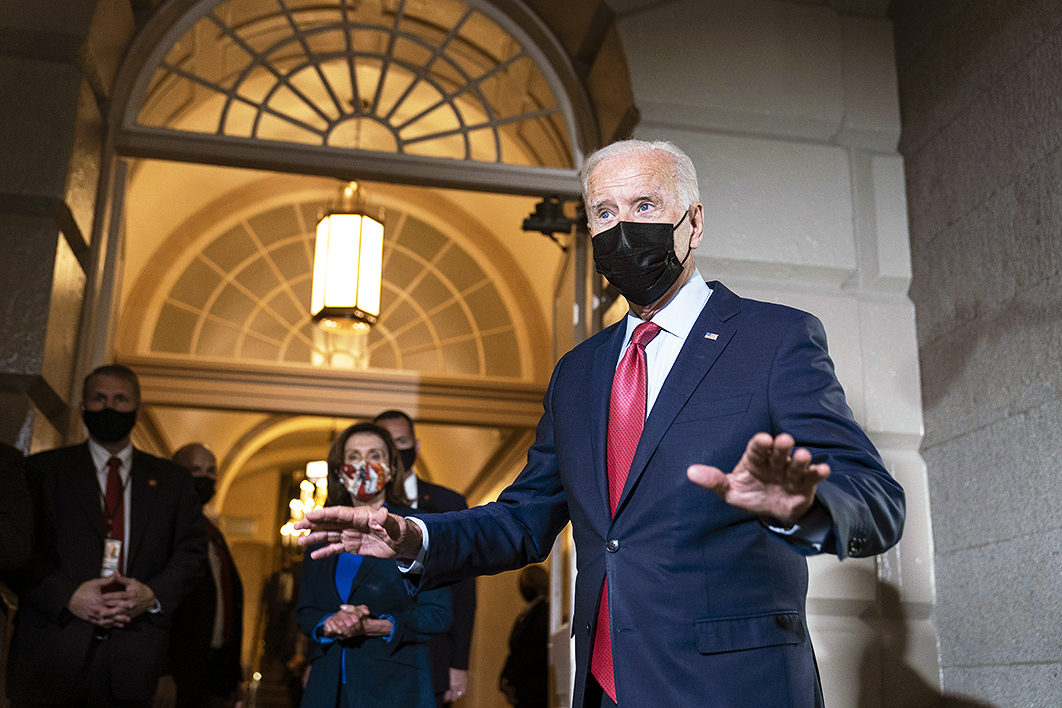

As progress on an agreement stalled on Friday, the president went to Capitol Hill for a closed-door meeting with House Democrats. Afterwards. his message was that the timeline is secondary to the content of the bill. “It doesn’t matter whether it’s in six minutes, six days, or six weeks,” he said. “We’re going to get it done.” Later reports revealed that he had indicated he would put the infrastructure vote on hold until Democrats pass his social policy and climate change package. Even though the infrastructure bill’s delay has already had consequences, he seems willing for it to continue for some time. Only emergency legislative action on Saturday to reauthorise the expiring transport programs in the bill prevented the furloughing of thousands of transportation department employees.

Weekend rumours suggest that Biden, Pelosi and Senate leader Chuck Schumer are telling Democrats that the final Build Back Better outlay will be US$2 trillion, on top of the US$1 trillion in infrastructure. That will require compromises on what can be funded. Underpinning such compromise is the fervent hope that Democrats across the ideological spectrum will recognise that a failure to agree will not only undermine the president and the party’s midterm election prospects, but also limit the opportunity for future legislative wins on gun control, voting rights, access to abortions, immigration and other important issues.

As E.J. Dionne, Bruce Wolpe and other commentators have pointed out, the drawn-out fight over Obamacare offers lessons for Democrats today. The protracted and ugly legislative saga that finally led to Obamacare’s enactment tainted what Americans thought about the bill and what it meant for them. Soon after, Democrats lost the House in the 2010 midterm rout.

What Biden is proposing is a massive across-the-board investment in the workforce, infrastructure, social programs, education and the environment that will make a significant difference in most Americans’ lives. Not only that: it is viewed quite positively even among Republican voters.

The fallout from 2010 shows why the Democrats must unite on a realistic compromise and get these provisions enacted quickly so that the results are already apparent in 2022. That offers the real possibility of overturning the killer history of midterm losses for the incumbent party in the White House. •