Cabinet records show that Australia went to war in Iraq in March 2003 with eyes fixed and brain narrowly engaged. The eyes were so set on the US alliance that the mind was made up. Lots of alliance loyalty, much less thinking and few questions.

Courtesy of the National Archive’s annual release of official papers, we also know that the cabinet record was unusually sparse. Before the conflict, not a single submission went to cabinet making the case for or against war, and none assessing the strength of intelligence reports on Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction, or WMD. In the three months prior to the war, Iraq generated twenty-four pages of cabinet paperwork, less than ministers would expect for a minor change to a federal law.

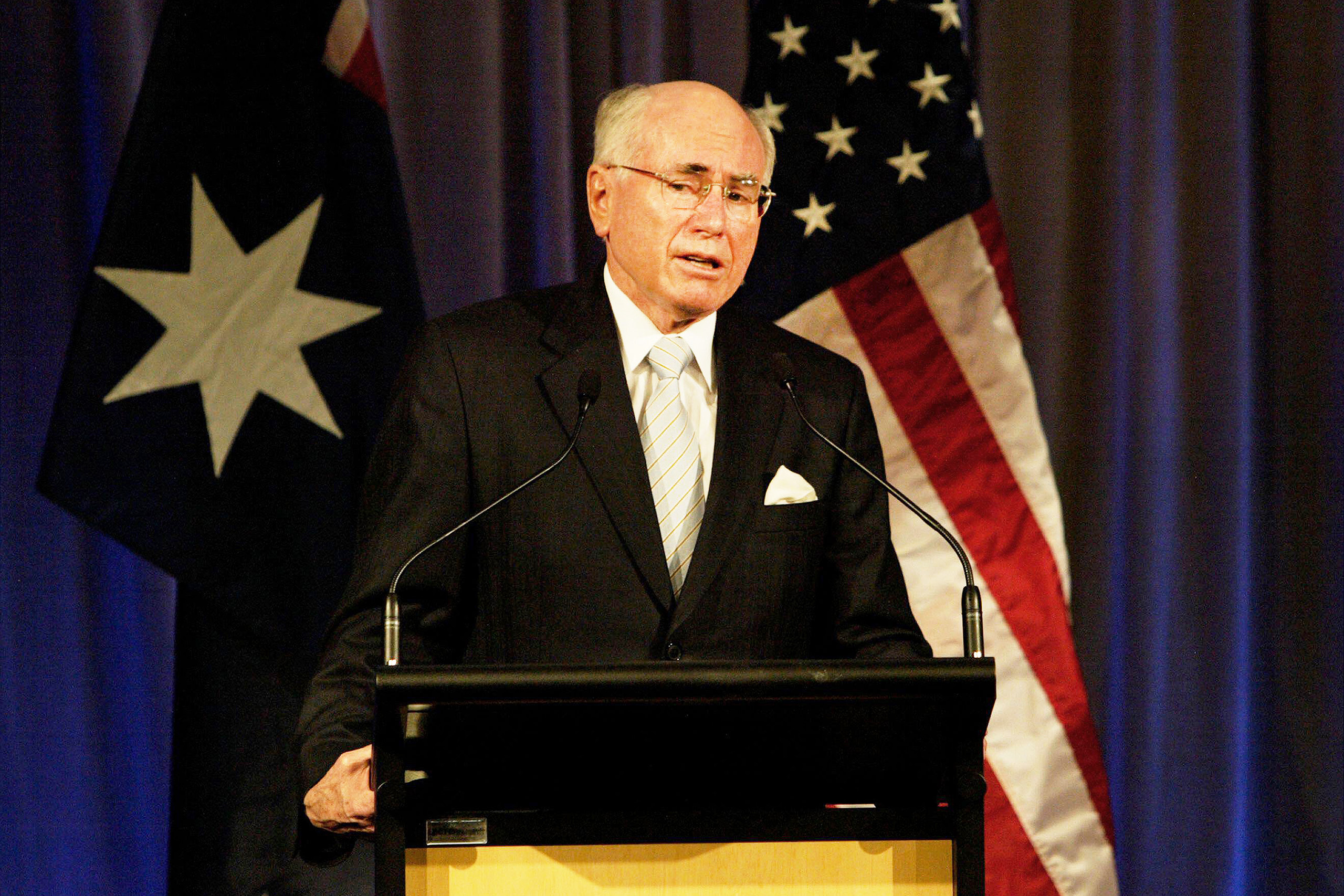

Iraq was prime minister John Howard’s great international blunder, but his political execution was masterful. A strong leader worked his cabinet, controlled his party and dominated the bureaucracy.

That mastery was built on the political fib that Howard was deeply pondering the option of not joining the United States in attacking Iraq. The fib was a function of the core reason Australia went to war — to serve its alliance with America. Howard treated any doubts about the Iraq commitment as a questioning of that irreplaceable strategic prize. In retirement, he declared it “inconceivable” that Australia would fail to enlist in a US war.

Howard took Australia to its “greatest” war of choice. All wars are a mix of necessity and choice, but Iraq is further out on the choice axis than any other Australia has fought. It makes Iraq the example of the prime minister’s prerogative to send Australia to war.

Not asked for advice, the public service didn’t speak. Written submissions pondering the life-and-death decision would have fuelled debate within the government and party and have been explosive if leaked.

The five-year path to war

Australia’s self-invitation to Iraq began five years before the war, at the start of 1998, when Canberra signed on to US military planning for Iraq. After Saddam Hussein had suspended cooperation with UN inspectors attempting to monitor Iraq’s biological, chemical and missile capabilities, the United States and Britain threatened military retaliation and began building up forces in the Persian Gulf.

Early in February of that year, Howard briefed cabinet on his Iraq discussions with US president Bill Clinton and the prime ministers of Canada and New Zealand, and on “recent decisions” taken by cabinet’s National Security Committee. Cabinet affirmed the NSC’s decision to “offer military support to the United States’ coalition,” namely special forces personnel, two air-to-air refuelling aircraft, and medical and intelligence specialists. For Howard, that “offer” became a firm commitment to all that followed.

Cabinet granted the NSC authority to alter the mix of military forces to provide “support of a similar magnitude” if what was offered “cannot be incorporated into US plans.” On 20 February, the NSC approved two sets of rules of engagement, or ROE, “a defensive ROE applying during peacetime and the second, if necessary, an operational ROE for use during conflict.” Both sets of rules provided for integration into a coalition force, with the Australian Defence Force under the “direction of the coalition force commander, with ADF elements to remain under national command.”

The 1998 push to war reversed after UN secretary-general Kofi Annan swung into action and Iraq stepped back. By March, the NSC noted Iraq’s “current cooperative approach” and the failure of fresh inspections to find evidence of WMD. In May, nevertheless, cabinet considered options for Australian military support for operations in the Gulf. The starting point was that the United States should maintain its commitment to the military coalition. ADF liaison officers should be integrated into the US land headquarters in Kuwait, the special forces headquarters in Kuwait, the air operations headquarters in Saudi Arabia, and the US Central Command in Florida. Australian officers would help the US plan to fight Iraq.

Alliance insurance is served by military integration. Yet integration can define and drive commitment. Once you’re in, you’re in. And by 2002 war with Iraq was looming.

Howard begins the Iraq chapter of his memoir with this sentence: “Speaking to the General Assembly on 12 September 2002, George Bush not only recited Iraq’s long record of defying the demands of the United Nations but made it clear that if the United Nations did not act, the United States would.” Parse the alliance grammar: the US is both the subject and verb. And for Howard, the United States was always the central object. US actions would drive Australia’s response.

The archive trail includes a two-sentence minute from 10 September 2002, two days before Bush spoke to the UN, noting that Howard gave cabinet an oral report on his discussions with the president “on the American position in relation to efforts by Iraq to secure and maintain weapons of mass destruction. The cabinet also noted that the US intended to make appropriate use of United Nations forums and processes in seeking to resolve the issue.”

The archive record is that of a government determined to act, marching to an alliance beat, working on how to go to war, not whether to go. The tempo of the march was set by Howard’s innovation in the machinery of cabinet — the National Security Committee.

When Howard took government in 1996, he created the NSC as the peak decision-making body for national security and foreign policy. Marking a significant shift in cabinet structure, it has been retained by subsequent governments. Unlike those of other cabinet committees, NSC decisions needn’t go to full cabinet for approval. Also unusually, ministers are joined at its meetings by senior officials, including the secretaries of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Defence and Foreign Affairs, the chief of the Australian Defence Force, and the head of the Office of National Intelligence.

As the authors of a history of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet comment: “At NSC, the officials sat at table in the cabinet room with ministers, even if on the other side, and could participate in discussions — although those discussions were led by, and the decisions were made by, the ministers. Howard wanted his ministers to hear the views of the defence and intelligence chiefs.” The gathering of ministers and officials in the cabinet room makes the NSC a strong and effective instrument, especially for a powerful prime minister with a clear objective.

The NSC was “meeting frequently” in the five months leading to the start of the Iraq invasion, according to defence secretary Ric Smith. “But it did not, in my time at least, address the big issue because by then the prime minister and ministers seemed to have a firm view about where they were going and why.”

On Iraq, a single omnibus cabinet document in 2003 tracks the detail of the NSC trek to Howard’s alliance objective. Titled “Iraq: Australian Contingency Arrangements for Possible Military Action,” the file contains a series of ministerial letters and NSC decisions covering the period from 10 January to 5 March.

The eighteen-page file records decisions on “contingency arrangements for possible Australian military involvement in any future United States-led military action against Iraq” (10 January); rules of engagement, policy on military targeting and the NSC’s agreement that the defence budget should be supplemented by $467 million to meet the costs of the Middle East deployment (18 February); arrangements following an invasion, when Australia should “promote a strong and visible UN involvement in the post-conflict management of Iraq” and “encourage coherent planning and sound policy settings for reconstruction, including by early engagement with international financial institutions” (5 March).

The decisions were based not on departmental submissions but on oral briefings and “letters” from ministers. On 27 February, foreign minister Alexander Downer wrote to the prime minister, copying the letter to other NSC ministers, about dealing with Iraq after “military action” and “conflict” (words such as “invasion,” “war” and “occupation” do not appear). Commenting on “US Phase V” planning for the administration of a defeated Iraq, Downer observed:

Our starting point has been that, while Australia will do its fair share, we do not have the resources to do the “heavy lifting” on Iraq reconstruction. You have made clear to President Bush that Australia will not be in a position to contribute to a post-conflict or peacekeeping or stabilisation force. There are however significant Australian commercial interests in Iraq which we would want to advance. And we have a strong political interest in ensuring that the institutional arrangements in post-conflict Iraq are credible and effective.

US Phase IV planning is now well advanced. It is increasingly clear that the US envisages a dominant role for itself in all sectors in post-conflict Iraq for as long as eighteen months, while relegating the UN to a subsidiary role, primarily through its humanitarian agencies. This position was reaffirmed to me by [US secretary of state] Colin Powell in Seoul on 25 February.

I doubt that the US position is sustainable and much will eventually depend on whether any US-led military action goes forward under UN cover. The UK shares our view that there needs to be a strong and visible UN involvement in the post-conflict running of Iraq and we should continue to work with the UK to press this position in Washington.

Downer’s two-page letter is as close as the cabinet documents come to discussing the meaning of the planned conquest, but it still doesn’t stray anywhere near the merits of the war.

With all the preliminary work done by the NSC, the one substantial document generated by the full cabinet before the war began was dated 18 March 2003. The six-page cabinet decision, “Iraq: Authority for Australian Defence Force Military Action,” has to do a lot of work as a key piece of documentary history on Australia’s choice for war.

The next day, 19 March, the bombing campaign started; the day after that, 20 March, the ground invasion began.

The cabinet minute notes “oral reports” by Howard on his “extensive discussions” with the US president and British prime minister about the use of force against Iraq. On the morning cabinet met, President Bush had requested Australia join “military action by a coalition to disarm Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction.” The rest of the minute is about accepting the Bush case for war — Iraq’s WMD were “a real and unacceptable threat to international peace and security” — and the mechanics of Australia’s military role. The cabinet decision is the final step in Australia’s march to war.

In making the Iraq commitment, Howard sidelined the governor-general, Peter Hollingworth, who has the constitutional power to declare war. The National Archives historian David Lee reports that Howard had originally planned to follow the constitution and take the decision to Hollingworth “for noting.” But Howard was worried by Hollingworth’s request for further advice on international law. Instead, the legal step was taken without reference to the governor-general using the ministerial powers of the Defence Act.

The intelligence agencies

Howard’s lingering mastery means his argument for joining a preventive war based on intelligence still gets a run. Two decades after the war, Australia’s defence minister in 2003, Robert Hill, maintained: “On the basis of the information we had at the time, we made what we believe was the right decision, and I still believe on the basis of that information that was the right decision.”

Such forgetting must overlook the conclusions of two Canberra inquiries: the joint parliamentary intelligence committee’s Inquiry into Intelligence on Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction and the specially commissioned Inquiry into Australian Intelligence Agencies.

Both reports showed Howard had little support from Australian intelligence agencies in deciding on war. The prime minister got just enough cover from the Office of National Assessments, or ONA, to meet political needs; beyond politics, the intelligence — as a basis for war — was thin. Parliament’s intelligence committee found that the Defence Intelligence Organisation was sceptical throughout about Iraq’s weapons, while the ONA, located within the Prime Minister’s Department, hardened its line as Howard marched to invasion. The committee commented on a sudden shift “in the nature and tone” of ONA’s view of Iraq’s WMD in September 2002: “It is so sudden a change in judgement that it appears ONA, at least unconsciously, might have been responding to ‘policy running strong.’”

To see how “policy running strong” bulldozes counter-arguments and unhelpful evidence, turn to a fine public servant who spent many years serving parliamentary inquiries — and writing much of what came to be tabled as committee findings. Margaret Swieringa was secretary of the parliamentary intelligence committee from 2002 to 2007 and put together its Iraq report. In retirement, she offered a withering analysis of Howard’s arguments about Iraq’s WMD. “None of the government’s arguments,” she wrote, “were supported by the intelligence presented to it by its own agencies. None of these arguments were true.”

Here is how Swieringa summarised the findings of the parliamentary inquiry she served:

• The scale of threat from Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction was less than it had been a decade earlier.

• Under sanctions that prevailed at the time, Iraq’s military capability remained limited and the country’s infrastructure was still in decline.

• The nuclear program was unlikely to be far advanced. Iraq was unlikely to have obtained fissile material.

• Iraq had no ballistic missiles that could reach the US. Most if not all of the few SCUDS that were hidden away were likely to be in poor condition.

• There was no known chemical weapons production.

• There was no specific evidence of resumed biological weapons production.

• There was no known biological weapons testing or evaluation since 1991.

• There was no known Iraq offensive research since 1991.

• Iraq did not have nuclear weapons.

• There was no evidence that chemical weapon warheads for Al Samoud or other ballistic missiles had been developed.

• No intelligence had accurately pointed to the location of weapans of mass destruction.

When the parliamentary committee report was released, Patrick Walters’ front page story in the Australian was headlined “PM’s Spin Sexed-up Iraq Threat,” a vivid rendering of what happens when a prime minister is running strong.

Howard could not allow that damning headline to stick. Hurt by one inquiry, a political master responds with another investigation with refined terms of reference. The PM called in a former diplomatic mandarin, Philip Flood, to inspect a failure — the failure of the intelligence agencies, that is. Flood’s conclusion began: “There has been a failure of intelligence on Iraq WMD. Intelligence was thin, ambiguous and incomplete.” He lamented a lack of rigour in challenging preconceptions or assumptions about the Iraq’s intentions. Sticking to his brief, his focus had to be on intelligence errors, not any blunders by political masters.

The old intelligence lessons of contestability and care endure. Intelligence is always partial, and partially wrong. The stuff that seems too good to be true can look good because it isn’t true (a truth as important for politicians or journalists as it is for analysts). Howard used the Flood report to blame failure on the Australian intelligence community. The punishment? Big increases in funding to do a better job.

The Iraq fib

John Howard’s story to the Australian people as he headed to war used a fib as a fig-leaf. The fib was deployed throughout 2002 and all the way to the moment of invasion in 2003. Australia had an open mind, said the fib. It was weighing the options and had yet to commit to a US-led attack. Even at the time, the fib was transparent. In the history of the open secret, it is a fine example.

I’ve used the word “fib” instead of “lie.” This political distinction is best not used when disciplining children or giving evidence under oath. The fib in its political garb is a thing of sophistry and silences. Some truth resides within it, but it is not wholly true. It is the politics-as-usual version of being economical with the truth. Neither a bent untruth nor a straight lie, the fib contains many shades of shadiness.

The truth in Howard’s fib was that if Saddam Hussein had totally surrendered — if he had revealed to everyone’s satisfaction that Iraq had no WMD — Australia would, indeed, not go to war. Saddam, though, would have had to convince the United States: not a simple task given the ambition and hubris of the Bush administration after what seemed like a successful invasion of Afghanistan.

Howard sets the terms of the fib in a brisk chapter on Iraq in his autobiography. The book recounts his White House talks in June 2002, where President Bush was given to understood that he “would keep my options open until the time when a final decision was needed.” But Howard writes that Bush also understood that “close discussions were under way between the US military and their Australian counterparts.” Bush was “entitled to assume on the basis of that, and also the tenor of our discussions” that he could rely on Australia’s military commitment. The “tenor” of that White House deal was a promise of support from Howard. Later, on the eve of the war, Howard gave a further personal pledge to Bush: “George, if it comes to this, I pledge to you that Australian troops will fight if necessary.”

The commitment to Bush was not, however, the story Howard gave Australia all the way to the invasion. The fib that Australia could step back and not join an American invasion was the public version.

The fib miasma held the government together, sidelined the public service, and provided that fig-leaf of cover as Australian public opinion turned decisively against the Iraq war. “Our decision to go into Iraq was against the weight of public opinion,” Howard wrote in his memoir. By January 2003, he noted, one poll showed that only 6 per cent of Australians supported joining an invasion of Iraq without a specific UN resolution.

Right up to the moment the guns started firing in March, Howard maintained that Australia had not made up its mind. In a statement to parliament on 4 February 2003, he again promised that “the government will not make a final decision to commit to military conflict unless and until it is satisfied that all achievable options for a peaceful resolution have been explored.”

Strange that a government agonising over such a choice asked no questions of its senior public service advisers. The reality was that all sides of Australian politics — and most of the Australian people — knew the commitment had long since been made. The ADF was deeply involved in US planning for the war and Australia was in.

American versions of the Iraq decision-making paint Howard as urging Bush, not cautioning him. In his memoir, Bush describes Howard as committed to action against Iraq, although preferably with UN backing; he writes that “almost every ally I consulted — even staunch advocates of confronting Saddam like prime minister John Howard of Australia — told me a UN resolution was essential to win public support in their country.” Bush lauded this staunch advocate as “a man of steel” and Howard steeled Bush to act.

When Howard appears in Bob Woodward’s account of the US invasion, the prime minister is urging Bush on. In an interview with Woodward, the president said Howard shared his “zeal” for the “liberation” of Iraq (along with Britain’s Tony Blair and Spain’s Jose Maria Aznar). Bush said they “all share the same zeal for freedom. It probably looks paternalistic to some elites, but it certainly is not paternalistic for those we free. Those who become free appreciate the zeal. And appreciate the passion.”

When the Bush and Howard met in in the White House on 10 February 2003, a month before the invasion, Woodward quotes Bush telling Howard that “thanks to your strong resolve we’re finally getting clarity.”

In his memoir Howard reflects that he committed Australian troops without bipartisan support and against public opinion: “Although the cabinet, most particularly my senior National Security Committee colleagues, unconditionally supported our stance, I had been the driving force behind the firm support we had given to the Americans. Both the party and the public saw this as something to which I had given a deep personal commitment.”

That “driving force” herded and harnessed Canberra.

The cabinet submission that never was

The public service silence on Iraq quickly entered Canberra lore. A year after the war, in a book on Howard, Bush and the alliance, journalist Robert Garran wrote:

Howard acknowledges there was no cabinet submission on the costs and benefits of going to war in Iraq. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was not asked for, and did not offer, any advice on the pros and cons of supporting American intervention. This reinforces the view that Howard’s decisions on Iraq were political, not based on a dispassionate appraisal of the threats it posed.

Garran’s footnote for that statement reads: “In an interview with the author on 12 March 2004, asked to comment on reports there had been no overarching cabinet submission on Iraq, Howard did not dispute the point, and answered that the issue was dealt with by cabinet’s National Security Committee.”

The journalist Paul Kelly observed that one of Australia’s most contentious conflicts “saw an astonishing and complete unity of opinion in Canberra.” He called this an insight into both strategy and governance: “Ministers made clear they did not want contesting advice and the public service offered no advice on the merits of the war or Australia’s commitment.”

Here is the modern version of the Canberra system. Frank and fearless advice is not an automatic requirement. If the prime minister has decided to go to war then don’t give him contrary advice. Certainly, don’t give him advice he hasn’t sought. And beware any senior bureaucrat who produces paperwork that could be leaked to attack or discredit the commitment to war.

The public service would attend to details; Howard and the NSC would do the rest. The secretary of foreign affairs and trade, Ashton Calvert, said his department’s task was to prepare for Australia’s Iraq role and make it work: “DFAT did not argue against that war role. In my view there was a strong and shared sense of policy direction on Iraq from Howard and Downer… In my view they didn’t need advice on what they should do because they had, in effect, made up their minds.”

When Ric Smith became defence secretary in November 2002, the message he got from ministers was that “they did not want strategic advice” from his department. “This reflected a conviction that ministers knew the issues and would take the decisions for or against the war.”

Making up your mind is one thing. Having a closed mind is a recipe for policy disaster. Australia would help to invade, conquer and occupy — then leave immediately. Iraq’s future? The consequences for the Middle East? Not our problem, thanks. All issues for the United States.

Consider what the Howard government could have known and asked in 2002 and early 2003 before committing to the blunder that became the Iraq war. No perfect hindsight is required; merely what cabinet could have focused on as it prepared to be part of an invading coalition.

If the big cabinet submission that never was had been ordered, what would have been discussed? Beyond military planning, such a submission would have covered intelligence, the nature and future of Iraq, the geopolitical balance in the Middle East, and Australia’s legal responsibilities as an occupying power. Then the submission would have drawn all the strands together to discuss the core driver of commitment — the alliance.

Intelligence

The WMD intelligence was thin, as Canberra’s two post-invasion inquiries found. Suffice to say that a government considering options would have wanted the intelligence stress-tested and argued over.

In a retrospective on the war in 2013, Howard argued that the “belief that Saddam had WMDs was near universal” while quoting the ONA’s view that the evidence “paints a circumstantial picture that is conclusive overall rather than resting on a single piece of irrefutable evidence.”

The strength of the intelligence was questioned by the chief UN weapons inspector, Hans Blix, when he met Howard in New York five weeks before the war began. At the meeting, Blix wrote later, “far from saying to Mr Howard that there were WMDs in Iraq I conveyed to him that we were not impressed by the ‘evidence’ presented to this effect. Regrettably, there were few at that time who cared to examine evidence about Iraq with a critical mind.”

As Blix later commented in a review for Inside Story of the memoirs of Howard, George W. Bush and Tony Blair, the three leaders relied on Iraq’s alleged WMD to justify invasion but “the evidence was nowhere to be found.”

The three leaders used intelligence as the basis for a preventive war, not just a political debate. If the intelligence was circumstantial rather than definitive, other factors should have weighed heavily, such as a discussion of what would happen in a conquered Iraq.

The nature and future of Iraq

As war loomed, many expert voices denounced the dream that a US-led war would transform Iraq into a peaceful democracy.

Ten years after the invasion, John Howard gave this version of what went wrong:

The post-invasion conflict, especially between Sunnis and Shiites, which caused widespread bloodshed, did more damage, in my judgement, to the credibility of the coalition operation in Iraq than the failure to find stockpiles of WMDs. Persecution by the pro-Saddam Sunnis of the Shia majority had been a feature of Iraq for the previous twenty years. It was inevitable that after Saddam had been toppled a degree of revenge would be exacted, but a stronger security presence would have constrained this.

Ponder how those thoughts would figure in the crucial cabinet submission that was never written. Take as the text for that submission an article published in the Australian six weeks before the war by Rory Steele, Australia’s ambassador to Iraq from 1986 to 1988. Offering a brisk survey of Iraq’s artificial nature as a country and the Sunni–Shia split, Steele judged that invasion would be the easy part. After that would come “the mother of all messes” as Iraq’s “abundant internal contradictions” turned to chaos:

New questions will arise daily, of legitimacy, of policing, in a situation of revenge killings, armed resistance and terrorism. With Iraq risking fracture, the coalition of the willing that entered may find it is in for a much longer and murkier haul than expected. Its hope will be to exit quickly, leaving Iraq in good order. The peacekeepers’ role could be thankless, dangerous and open-ended.

This was no 20/20 hindsight, but advice offered before the invasion. Having pondered that dark vision, the cabinet submission that should have been written would then turn to the impact on the Middle East of the mother of all messes.

Middle East geopolitics

Howard always presented himself as a tough international realist rather than a mushy multilateralist. Yet he had little regard for the realist views he accurately summarised a decade after the war:

The realists were probably untroubled by the UN issue, likely believed Saddam had WMDs, and regarded him as a loathsome dictator. Despite this they saw merit in continuing a policy of containing him and eschewing resort to military action. To them the world was too dangerous a place to become involved in such action except in the most compelling circumstances, which they did not think existed in Iraq in 2003.

The war’s disastrous impact on the geopolitics of the Middle East was predicted by many — not least a generation of US policy-makers who could not make George W. Bush listen.

After throwing Iraq out of Kuwait in 1991, president George H.W. Bush (the senior and wiser Bush) stopped short of toppling Saddam from power. The argument he made to Australia and others had a public and private dimension. The public line was that freeing Kuwait was the extent of the UN mandate. The private version was that deposing Saddam would destroy the regional power balance and that remaking Iraq would be a vast endeavour.

The US secretary of state in 1991, James Baker, wrote in his 1995 memoir that if the US had marched on to Baghdad after taking Kuwait, “Iraq might fragment in unpredictable ways that would play into the hands of the mullahs in Iran, who could export their brand of Islamic fundamentalism with the help of Iraq’s Shiites and quickly transform themselves into the dominant regional power.”

In the power realignment, the big winner would have been Iran, no longer balanced by Saddam’s Iraq. The United States would deliver regional victory to Tehran, aiding the regime it hated most. It was a strong realist argument in 1991 and it needed to be considered in 2002–03. It also turned out to be true.

Australia as an occupying power

An invading power is responsible for the country it conquers. Arguing with his president, US secretary of state Colin Powell compressed this international responsibility into a single image — Bush would “own” Iraq — that evoked the pottery shop rule, “You break it, you own it.”

The imagined cabinet submission would have needed to consider Australia’s obligations to the state it had broken. After Australian forces helped overthrow Saddam, Howard was asked on 17 April 2003 if Australia was “an occupying power.” The prime minister replied: “We have the obligation of an occupying power under the Geneva Convention. We, along with the Americans and the British have responsibilities, certainly, and we won’t neglect those responsibilities.” Howard said Australia had an obligation to the people of Iraq to help establish a new democracy, and expressed the view that “the predictions of a civil war are unduly pessimistic.”

Howard’s embrace of occupying-power responsibility was another fib: the fleeting words of a radio interview, not a government commitment. Australia invaded, then fled, declining a role in governing postwar Iraq. Canberra refused to sign on for that legal responsibility at the United Nations, leaving it to the other members of the military coalition.

UN Security Council resolution 1483 in May 2003 attributed only to the United States and Britain the status of occupying powers. It noted that on 8 May the two countries had written to the Security Council claiming “the specific authorities, responsibilities, and obligations under applicable international law of these states as occupying powers under unified command.”

The US alliance and Howard’s view of his masterful blunder

Having dealt with those four dimensions of the looming war in the submission that never was, cabinet would have turned to the central concern: what Iraq might mean for Australia’s alliance with the US.

A single sentence in the penultimate paragraph of the Iraq chapter in Howard’s autobiography expresses the foundational view that took Australia to Iraq: “I found it inconceivable, given our shared history and values, that we would not stand beside the Americans.” Howard was confident the United States would win, and that Australia would do its duty. Much history underpins that “inconceivable” conviction.

In the years since the United States came to Australia’s rescue during the second world war, Australia has trooped to America’s wars — Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. A singular purpose runs through Australia’s role in these wars: the US alliance. Canberra invites itself so it can pay its alliance dues. Paying the insurance premium explains much about Australia’s longest war in Afghanistan and our role in Iraq.

The self-invitation process can be swift and built on high emotion, as it was when communist forces invaded South Korea in 1950 (Australia’s quick response helped clinch the ANZUS alliance) and in Afghanistan after the 11 September 2001 attacks on America.

The 1991 Gulf war sits close to this category but doesn’t quite fit the “America’s wars” typology. In the first exuberant moments of the post–cold war era, Australia went to the Gulf to support the United Nations and international law by overturning Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. The multilateral interest might have been of equal importance to the US alliance. The balance of interests meant that Australia’s contribution was primarily naval; no boots on the sand in 1991 and no Australians in combat.

At other times, as in Vietnam and Iraq, a step-by-step journey builds until it culminates in an Australian commitment. This is not sleep-walking to war. Many debates and decisions are involved. But a sense of narrowing options, even inevitability, can grip Canberra, building a sense of alliance necessity. The premium must be paid.

Australia did a better job of military preparation for Iraq than it did for Vietnam. Australian officers were embedded in the US system and took part in a prolonged period of military planning. In Vietnam, by contrast, the location of Australia’s first deployment was decided by the US military and advised through diplomatic channels. Australia went into Iraq far more cautiously than it did in Vietnam and got out as the dust of invasion cleared. We were slowly drawn back into Iraq by alliance demands in later years but, again, the military commitment was limited and confined. That is why the price paid in Australian blood was low, with two Australia military personnel killed between 2003 and 2009.

Examining the Vietnam–Iraq echoes, former Australian diplomat Garry Woodard found an “astounding durability” in Canberra’s alliance mindset, marked by “the dominance of the prime minister, decisions made in secret by a small group of ministers obedient to him, minds closed against area expertise, preference for party political advantage over bipartisanship, and willing subservience to and some credulity about an ally, the United States.” Woodard listed fifty Vietnam–Iraq parallels, including:

• Advice that ministers don’t want to hear won’t be heeded.

• The focus of Australian decision-makers is the US alliance.

• Australia will be part of a coalition of two or three if necessary.

• Australia’s assessment of the US is personalised and presidential qualities weigh heavily in that assessment.

• Australia relies heavily on US intelligence.

• There was no exit strategy for either war.

• In both cases, Australia put its standing in Asia at risk.

As Woodard judged, these are “enduring features” of Canberra’s decision-making. Howard exemplifies those features in his alliance commitment and the way he drove the government.

In December last year I questioned Howard on those issues during a media briefing at the annual release of cabinet records held by the National Archives.

One of my questions was based on the history offered from Washington in the books by George W. Bush and Bob Woodward. Both accounts, I said, painted Howard as an advocate of the war, not a caution. The Bush memoir described him as a “staunch advocate.” But the word that caught Howard’s attention was Woodward quoting Bush’s view about Howard’s “zeal” for the Iraq cause.

“My what?” Howard responded.

“Your zeal to go after Saddam,” I said.

“His word, not mine,” Howard said.

“Indeed, his word,” I said, “but were you an advocate rather than a caution in terms of the war?”

Howard replied that “zeal” would be a label more appropriate for Britain’s prime minister, Tony Blair, and his “huge commitment” of 45,000 British troops to the war.

“He believed in it very strongly,” said Howard. “Now, was I zealous? I think ‘zeal’ is slightly overstating it. You imply my role was to act as a cautionary friend. Well, you’re entitled to that view. I thought my role was to assess the Australian national interest, and that’s above all what I was sworn to uphold. I thought I pursued that because I thought it was in our national interest to put a curb on the capacity of terrorists to get hold of weapons of mass destruction from Saddam. I believed at that time that he not only had programs but he had stockpiles. I thought it was in Australia’s national interest to listen carefully to assessments of international reality and situations by our close friend and ally, the Americans.”

I’d prefaced my questions about the government process with a quote from Howard’s memoir, where he stated his aim to run “a fully functioning and orderly system of government.” My questions were: “Why in the decision to go to Iraq did you not use the system that you’d set up? Why were there no submissions from the public service on the intelligence? Submissions from the public service on the Middle East process? On what would happen in Iraq? Instead, the documents we do have — and there aren’t many — are basically letters to you from ministers and oral briefings. So why did you follow that, if I might say, rather unusual process, running it through the NSC?”

“What you’ve got to understand about the NSC,” Howard responded, “is that’s where all of detailed discussions about Iraq took place. There wasn’t one, single cabinet submission that you could isolate. But over a period of months we discussed in detail what was happening in Iraq, what was the current state of the intelligence and all of that. It was just a rolling process. Now you’re entitled to make the point, ‘Why was there at least one omnibus submission that covered everything?’ Well, it was pretty hard during that time to cover everything, because different events unfold.”

He went on: “When the Americans finally decided to push the button, they had to come to us to tell us, then they had to come back to get the result of a cabinet decision. And it was, from a legal standpoint, perfectly open to Australia to decide even at that late point, for one reason or another, that we wouldn’t go ahead. However, I never had that in mind. Certainly not. I think that would have been verging on the deceptive to a close ally to have behaved in that way. But it was, nonetheless, a legal decision.”

A decade after the war, Howard had offered this key sentence: “Australia’s decision to join the Coalition in Iraq was a product both of our belief at the time that Iraq had WMDs, and the nature of our relationship and alliance with the United States.”

Don’t be misled by the order Howard gives. Notice the weighting of the words: the issue of the moment feeds into the permanent interests of relationship and alliance. Given the strength of the two issues in the Howard universe, my estimate of relative importance is US alliance 75 per cent, Iraq WMD 25 per cent. And even that probably underestimates the alliance premium.

The Australian Army’s unofficial history of the war, produced by the Directorate of Army Research and Analysis, concluded that Howard went to war solely to strengthen the alliance. It dismisses as “mandatory rhetoric” Canberra’s other claims about enforcing UN resolutions, stopping the spread of WMD and global terrorism, and remaking Iraq.

Only the alliance was a strong enough reason for Australia to join the United States in launching war. At huge cost to the United States and many others — but relatively little cost to Australia — the purpose was met. Washington made one of its greatest strategic blunders; Canberra served the alliance. On this reading, Australia shouldn’t care whether the United States wins or loses as long as the alliance is burnished.

But does Australia bolster its alliance credentials by cheering on Washington as it plunges into folly and quagmire? Disasters that sap America’s treasure and national psyche hurt its ability to meet the alliance promises Australia so values. A principal concern for Canberra ought to be the harm the United States does to itself, diminishing its ability to shape the world to its (and our) advantage. This is the great blunder in Howard’s political mastery.

In writing about Iraq, Howard demonstrates that the necessary act of political will — the choice — at the heart of the alliance can take on an automatic tinge. That’s what happens when the pact is elevated from vital to sacred.

Australia had never before launched a war. In Iraq we did. Consider our catalogue of conflict: Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Vietnam, Malaysia’s confrontation with Indonesia, Korea, the second world war, the first world war, the Boer war. In no case, apart from Iraq, was Australia the aggressor. We mobilised and joined alliances in response to attack, playing defence, not offence. (The Boers and Vietnamese might argue, but the regime-protection, defence-not-offence model can encompass those conflicts.)

A cabinet that truly debated its options in 2003 would have had to contemplate “doing a Canada” and refusing to join the invasion. We would have avoided a war of choice that was really a war of aggression. Howard’s tight hold avoided a dangerous discussion of the possibility that the closest of allies can say “no.” Refusal would have crashed against the prime minister’s personal pledge and deepest beliefs. Australia would have stepped back from a campaign it helped plan.

Surveying the Iraq disaster, one of Australia’s great foreign policy realists, Owen Harries, judged that “uncritical, loyal support for a bad, failed American policy” would hurt Australia’s standing as an ally in the long run. His dry but devastating denouement: “A reputation for being dumb but loyal and eager is not one to be sought.”

The lack of any Iraq WMD meant the reason for the “dumb but loyal” choice soon stood alone as the sole justification: Australia would go all the way with the USA. Iraq was the means. The alliance was the purpose. Squibbing a role in the conquered nation, Howard was deeply committed but not responsible. The US hubris was massive, and we drank of it. •