Jørn Utzon and Richard Johnson are facing each other across a table strewn with drawings and sketches in a room bathed in light. It is November 2001 and Utzon is giving his heart once more to his masterpiece on Sydney Harbour, the most famous of all his creations and the one that has caused him more anguish than any other. An old man now, re-engaged with a young man’s passion for the building he abandoned a lifetime ago, the great Dane leans closer to his Australian collaborator. “I have dared to make a tapestry,” he says, passing a vibrantly coloured drawing across the table.

Utzon has been explaining to Johnson the need for an acoustic dampening curtain in the refurbished Reception Hall of the Sydney Opera House, the first stage of a $69 million overhaul of the building’s interiors. “I have dared to make a tapestry for this inner wall,” he says again, in a private video shot at his house in Mallorca, “which has movement, like the forward rhythm of music, with glimpses of explosions of violins… with gold or silver threads and marvellous colours in wool.”

The tapestry means a lot to Utzon, and the story of its creation, as he tells it to Johnson, says a great deal about the peculiar nature of his genius. It was composed to the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, whose Hamburg symphonies delighted the architect’s spirit. “I wanted to take the division of time in his music for my division of movement in the tapestry, with the colours illustrating the various solo instruments and deep tones.” With Bach as his soundtrack, Utzon made a collage from rough-torn strips of coloured paper, painstakingly assembled and adjusted to the rhythm and progression of the music. Utzon’s inspiration was not Bach, however, but a painting by the Italian Renaissance master Raphael that shows Jesus Christ along the Way of the Cross.

“I copied it to see what is in it because I liked its rhythm,” Utzon explains, retrieving a loose sketch he made of the Raphael and passing it to Johnson. “And I was listening to music and the idea came to me that you could make a musical expression in the form of a painting. I wanted to make a tapestry that is linked to the traditional art of music, which intensifies the experience of the building. When you work as an architect or artist and you get a glimpse of a vision, you are open to a lot of ideas.” Utzon’s hope is that Johnson can convince the Sydney Opera House Trust to accept his proposal for a tapestry. “If you can get that through I will be very happy,” he says to the Australian architect. “No other picture except this one moves so beautifully forward.”

Johnson must have done his job well for, when the refurbished Reception Hall is unveiled, the 2.7 x 14-metre tapestry, Homage to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, will be its centrepiece. Utzon will not be present — at eighty-six years he’s too frail to make the journey — but the occasion will be a symbolic homecoming all the same. The man will be reunited with his magnificent obsession, and the world will get a further glimpse of what might have been.

Tucked away within the building’s podium, the Reception Hall (since renamed the Utzon Room) was one of the few Utzon interiors to survive his departure from the project in February 1966; structurally at least. But by the time the Opera House opened in 1973, the hall’s bold concrete walls had been covered with folded panels of plywood and its floors hidden under green carpet. Worst of all, its mighty canted concrete beams had been concealed behind a plywood wall. The restored hall, executed by Johnson from Utzon’s simple and exquisite sketches, is everything that it was intended to be. The folded concrete ceiling beams — badly stained with cooking fumes, dust and oil smoke — have been stripped bare, cleaned and buffed to a lustrous chalky grey. The carpet has been lifted and replaced with parquet flooring of Australian southern blue gum, rubbed with soap flakes to produce a protective milky finish. The concrete walls have also been exposed and buffed, while the kitchen and services have been relocated, hidden behind a sliding wall of blue gum. And Utzon’s magnificent tapestry, the focal point of the restoration project, hangs on the inner wall, facing the long window and the harbour beyond.

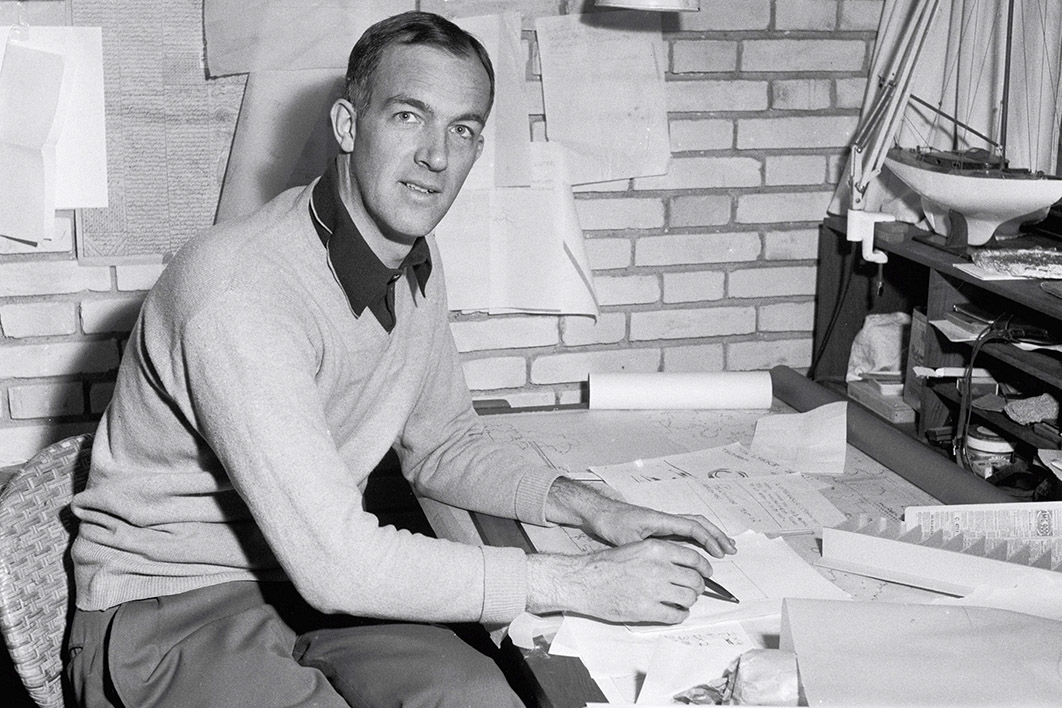

In a profession bursting with egos, the close working relationship between Utzon and Richard Johnson, one of the principals of architects Johnson Pilton Walker, is a curious one. Johnson, who designed the new Asian galleries at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, has deliberately taken the back seat. Where other architects of similar standing might have found it irresistible to put their own stamp on a collaboration with Utzon, Johnson feels “immensely privileged” just to be there. “The rare distinction of working frequently and long with this man is of enormous benefit to me,” he says. Utzon, formally re-engaged by the NSW government in 1999, is the principal architect and concept designer for the refurbishment of the Opera House. In this capacity, he has written a set of guidelines — the Utzon Design Principles — to describe his broad vision for the building and to serve as a permanent reference for its management and conservation. As part of the re-engagement, Utzon has chosen to oversee certain projects, such as the Reception Hall, in very fine detail.

At its simplest, the collaboration goes like this: Johnson is Utzon’s man on the ground, the interpreter of the new designs, the one who makes it all happen. “I’m here to do those things that are necessary in dealing with the client and authorities. I’m also here to help with the building. There’s a practical interface that’s required in carrying out the work. I coordinate all of that.” Between them stands Jan Utzon, the son, as his father’s eyes and ears. Jan looks after the technical drawings and, like Johnson, travels back and forth between Sydney, Denmark and Mallorca.

“It is an intensive way of working,” Johnson says. “We make prototypes; send bits back for his comment and approval. He is back working in a way that he is familiar with. His process of design, integrating drawings, model samples, prototypes, mock-ups, materials research and working in close collaboration with manufacturers is central to understanding his work. Nothing is introduced into the process before it has been carefully investigated and proved to be the right solution to the problem.”

The reality is that Johnson has played a very important role in identifying problems with the building’s interiors — poor acoustics, cramped orchestra pits, crowded foyers — producing a strategic building plan, which he put before Utzon for discussion and resolution. It is a useful process, according to Johnson, because at a distance of forty years Utzon could not be expected to know all the problems of the interior spaces he never got to finish. “The original brief was for an opera theatre and concert hall, but it was expanded to at least five uses after Utzon left. Of course, the building envelope hasn’t changed and the pressure on back-of-house today is extraordinary. The strategic building plan tries to look at a balance of solving the functional problems and in the process recreating Utzon’s vision for the interiors.”

But Johnson’s role goes way beyond practicalities, and Utzon’s renewed love affair with the Opera House is due in large part to the Australian’s reassuring presence. “It has taken a few years since you were re-engaged for everyone to realise how important a moment this is,” he told Utzon in 2001. “If you inject your spirit into the building, and we use the opportunity to work with you to re-energise the building, then it is a marvellous opportunity.” Back in Sydney and walking around the building, describing some of the Utzon-designed changes he is realising, Johnson describes his involvement as an enormous responsibility. “It is not something you take on lightly,” he says. “I was a student in 1966 and I remember what happened.”

What happened on 28 February 1966 is still not fully understood. On that day, nine years after winning an international competition to design an opera house on Bennelong Point, Jørn Utzon walked from the project, taking the blame for delays and cost overruns of gigantic proportions. The break occurred during a meeting with Davis Hughes, public works minister in the newly elected Askin coalition government, who was withholding $103,000 owed to Utzon for completed machinery contracts. Utzon apparently threatened to resign, walked out of the meeting and followed up later that day with a letter to Hughes, which stated: “You have forced me to leave the job.” Hughes responded almost immediately, accepting what he described as Utzon’s “letter of resignation.”

In an interview in the Weekend Australian Review, Utzon’s daughter Lin Utzon said, “I don’t think my father really thought they would take him up on it when he said, ‘If you don’t pay me my salaries and you don’t give me an opportunity to continue the work, it’s impossible and I will have to leave.’ I think he imagined that they would have a dialogue, but they just said, ‘Very nice to have met you, Mr Utzon. Have a nice trip back.’”

Weeks of talks aimed at resolving the impasse amounted to nil and on 28 April 1966, Jørn Utzon left Australia, never to return. One hour after his departure, his name was removed from the head of the project board on the concourse beneath the great stairs of the Opera House.

Yet Utzon has never stopped thinking about his unfinished business in Australia. In October 2003, writing to congratulate Bob Carr on his re-election as NSW premier, he described the Opera House as “a work that I’ve never really ceased to be involved in… Even in the period between when I left Australia in the 60s and until my re-engagement on the Opera House in the late 90s, I have constantly felt the presence of the Opera House close to my heart, and of course often wondered if I could have acted differently back then, in a way which could have made it possible for me to continue the work.”

Johnson fully understands Utzon’s complex relationship with the building, and while he does not say it explicitly, he has played an important part in resolving some of the older architect’s ambivalence. “When the opportunity arose to carry out refurbishment work on the interiors of the building, the question was raised about how to involve Utzon,” he says. “And what better way than to go back to the person who created it, because many of his ideas were never realised.”

Today, Johnson says the master is back, fully involved with his masterpiece. “He’s fascinated with the idea. He’s thrilled and derives enormous joy from working on it again.” In a wicked twist, Johnson has ensured that Jørn Utzon’s name is back at the head of a replica project board installed for the refurbishment works. Only the supporting cast has changed. •

This is an edited extract from Harry Seidler’s Umbrella: Selected Writings on Australian Architecture and Design, by Joe Rollo, published earlier this month by Thames & Hudson Australia). First published in the Weekend Australian Magazine in 2004.