In May and June 1940, with Britain facing the prospect of invasion by Germany, Winston Churchill’s government interned all German and Austrian men aged between sixteen and sixty who were living in Britain. The government feared they might form a “fifth column” in the event of invasion. On 10 July, 2000 of these men, most of whom were Jewish, were herded aboard the HMT Dunera at Liverpool and deported to Australia, where they were to be interned for the duration of the war. These men are now commonly known as the “Dunera boys.”

In most cases, their internment didn’t last the war. The British and Australian governments recognised the injustice of their situation, and the fact that they posed no threat, and from 1941 offered them paths out of internment. Those who stayed in Australia during the war were eventually given the option of permanent residency, and about 900 remained. In ways big and small, grand and humble, they helped build postwar Australian society.

In early September each year, members of the Dunera Association gather in the town of Hay in southwestern New South Wales to remember and celebrate the Dunera story. September is when the Dunera docked in Melbourne and then Sydney, and Hay is where most Dunera boys were first interned in Australia. Few are still alive – the youngest is ninety-two – and fewer still attend these occasions. At Hay in September 2015 there were two: Bernhard Rothschild and Werner Haarburger. Some people we met at the reunion were convinced Ken was a third. One conversation I heard went like this:

Questioner: “What are your feelings on returning to Hay, seventy years later?”

Ken: “I wasn’t on the Dunera. I’m an interested observer.”

Classic Ken: understated and modest.

Questioner: “Is it hard to return to where you were interned?”

Ken: “I wasn’t interned.”

After a pause, his questioner continued:

“Well, thank you for coming back. The presence of Dunera boys makes the weekend all the more special.”

I wanted to invent a backstory for Ken and run with it – turn Ken Inglis of Preston, Victoria, into Klaus Ingel of Potsdam, Germany – but he wouldn’t have it. Here is evidence of Ken’s commitment to truth and accuracy. What it says about me as a historian I’m not sure.

Though not one himself, Ken’s links to the Dunera boys are long and deep. His interest in their story spans seventy years, and now he is writing about them. Here I tell of some of their shared history, and offer my views on what Ken brings to the study of Dunera.

In 1947, Ken Inglis left home for the University of Melbourne. He had earned himself two scholarships: one subsidised a Bachelor of Arts, and the other covered meals and board at Queen’s College. For a callow seventeen-year-old from Preston in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, Queen’s was a thrilling new world. Under Dr Raynor Johnson, master of the college since 1934, Queen’s had become the most diverse and international of the university’s colleges, a home to staff and students from beyond Melbourne and Methodism. At Northcote High and Melbourne High, Ken had been aware of students from overseas, but most of these reffos, to use the idiom of the day, lived and studied beyond his Anglo-Celtic social circle. Not so at Queen’s, which in the 1940s was home to three men from the Dunera: Leonhard Adam, George Duerrheim and George Nadel. European, and exotic for it, they represented a new and different kind of person for Ken.

Dr Leonhard Adam had arrived at Queen’s in 1942, his release from internment arranged by charitable organisations sympathetic to the plight of the Dunera internees. Fifty years old, he had served the Kaiser in the first world war, and had enjoyed a successful career as a legal scholar and judge in the Weimar Republic. In the years before the second world war he left the law for anthropology, building a reputation as an expert on primitive art, and it was in this capacity that he was employed at the university. Ken remembers him sitting erect and proud at high table, a dignified figure.

Duerrheim also sat at high table, and next to the master and other staff in the annual college photo, though he was a student. In these photos he looks forlorn and older than his age. He had come to the university and Queen’s in 1943, aged thirty-five. His place at Queen’s was tribute to Raynor Johnson’s worldly interests and religious pluralism. Duerrheim was a Roman Catholic, classified Jewish by the Nazis, living in a Methodist institution. He hoped to finish the medical degree he had very nearly completed in his native Vienna. The German annexation of Austria in 1938 and the adoption of Nazi race laws had led to his being barred from sitting his final exams. British-minded medical authorities in Victoria, the state with the most rigid rules on doctors’ qualifications, took little heed of these studies and his extensive practical experience, and insisted he join the Melbourne medicine course at second-year level: five more years of study to achieve what the Anschluss had denied him. Duerrheim died young, in 1965. He practised medicine for not much longer than he studied it.

Duerrheim and Adam were benign figures. George Nadel, born in Vienna in 1923, was dark and mysterious. Jim Morrissey, a Queen’s resident, called him “Old Black Daddy,” a nod to his shadowy ways. The archaeologist John Mulvaney, who knew Nadel as a fellow history student, thought him a “con man of some proportion.” Ken, choosing his words carefully, says Nadel was “wily,” “ruthless,” “ludicrous” and intellectually brilliant. Nadel achieved first-class honours in history in 1948, a golden year in a golden age for Melbourne history, then decamped to Harvard. He founded the scholarly journal History and Theory, published to this day; Isaiah Berlin and Raymond Aron were among its first contributors. Mulvaney had it that Nadel’s other great achievement was marrying a Rockefeller, but of this we’re yet to find corroborating evidence.

In 1947 Ken knew of Adam, Duerrheim and Nadel as Europeans and reffos, but not of their connection to the Dunera. As yet, the name of that ship meant little to him. It came to mean more in 1948, when Ken took Franz Philipp’s course in renaissance and reformation history.

Philipp was an art historian from Vienna who, after the journey on the Dunera, internment, and service in the Australian army, found a home in Max Crawford’s history department. He was quiet and gentle, an uncertain lecturer whose words, mumbled with a heavy accent, were hard to follow. Another characteristic was his eye for ability. He spotted Arthur Boyd – Philipp wrote the earliest scholarly review of the young artist’s work – and he spotted Ken. After reading Ken’s “mature and scholarly” essay on Machiavelli, Philipp suggested he consider an academic career. For the young man from Preston with a love of words and writing, it was an exhilarating prospect; one, Ken notes, he “hadn’t dared to entertain.” The man from the Dunera set Ken on his way to a career as a scholar.

Philipp was one of several scholars from the Dunera who found employment at the University of Melbourne. Some Ken encountered in the course of academic life or at parties, where they occasionally talked of the past and their journey from Europe. Ken listened, snatching words about Dunera here and there and learning more of their stories. Were these men typical of the Dunera internees, he wondered. The few he knew were all intellectuals. In politics were Hugo Wolfsohn, tutor, and the precocious Henry Mayer, student. Both were dynamic contributors to university life, and to Ken daunting and formidable figures. “Mayer and Wolfsohn were a fearsome pair,” he writes, “prowling the Arts building and the Union like bears hungry to feast on our dogmas and confusions, especially those deriving from Karl Marx.” Mayer especially was everywhere; a vocal member of undergraduate societies, author of firebrand articles for campus publications, and in 1949 editor, with Max Corden, of Melbourne University Magazine.

Kurt Baier and Peter Herbst were in philosophy. Ken took a unit of philosophy, for which Herbst was his tutor, and attended other lectures out of interest. Baier’s lectures were worth it. “High calibre” and “intellectually penetrating,” John Mulvaney called them. Gerd Buchdahl was another Dunera reffo in Ken’s circle. Ken heard him give a seminar paper to the history department on the evolution of scientific thought from Kepler and Galileo to Newton, and what it was that Newton knew that the others didn’t. “It was a superb piece of intellectual history,” Ken recalls. “Gerd had everything as a lecturer.” Buchdahl went on to found the study of history and philosophy of science at Melbourne and at Cambridge.

Ken has told of the personal and academic satisfaction he derived from his time at the University of Melbourne. The scholars from the Dunera didn’t make these years, but they added to them, giving him glimpses of worlds he hardly knew. Many had a sophistication he admired.

Dunera boys and their stories followed Ken beyond the University of Melbourne. In Oxford in 1954, he and his wife Judy welcomed Gerd and Nancy Buchdahl and Peter and Valerie Herbst to their flat. Judy had her own connections. She was close to Peter in particular, who had been teacher and colleague at Melbourne, where she had studied philosophy and achieved first class honours in 1950. Arguing a point about the Dunera, Buchdahl and Herbst, both of whom spoke perfect English and favoured high diction, resorted to name calling. “Nonsense, you stinkpot.” “Don’t talk to me like that, you shitbag.” More than sixty years later, Ken tells this story with relish. He remembers the scene as vividly as any from his time at Oxford. Two German refugees and Anglophiles, once interned in the Australian bush, mixing profanities and scholarly wisdom in his flat in Oxford. It’s a good story.

Herbst became professor of philosophy at the Australian National University, where Ken also taught, and their friendship continued. Other Dunera friends in Canberra included Fred Gruen, an economist and neighbour in the Coombs building at ANU, and Klaus Loewald, a historian who lived near Ken and his second wife, the writer Amirah Inglis, in O’Connor.

Loewald’s story is remarkable. Born into a Jewish family in Berlin in 1920, he escaped the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938 by staying on the move, resting at night on trains rather than at home. In London he worked in a factory job before his arrest and deportation to Australia. Released from internment in 1942, he served in the 8th Employment Company of the Australian army alongside other former Dunera internees. He returned to London in 1945 and emigrated to the United States the following year; there, he took American citizenship and built an academic career. In 1962 he left Berkeley for Saigon to teach American politics and history at the university and to serve as American cultural attaché. He resigned from the US diplomatic service in 1970 in protest against the Vietnam war and Nixon’s presidency, moved to Australia with his wife, and joined the history department of the University of New England. He died in 2004 without having travelled to Hay with Ken, a trip Loewald had suggested they make.

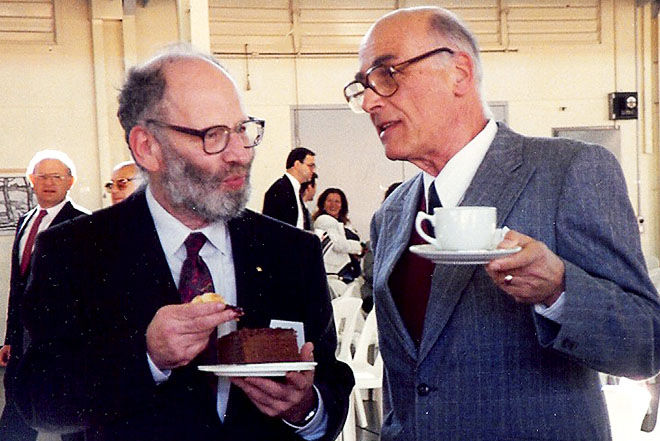

Historian and former diplomat Klaus Loewald (right), shown here with fellow Dunera internee Hans Marcus on the fiftieth anniversary of the vessel’s arrival. Rebecca Silk

Through these years Ken tried to interest his postgraduate students in writing about the Dunera, but never had any takers. Deep into retirement, he decided to tackle the job himself. He’d begun to sketch out a memoir when he reached the late 1940s and was distracted by Franz Philipp. Why write about his boring old self when he could write about Dunera, Ken thought. Classic Ken. He had no German, but he knew Dunera boys, and that scholars and film-makers hadn’t told all their story. And so he set sail on the bad ship Dunera, as he sometimes calls it. While I’m glad he did, I wish we could have had both histories: Ken on the Dunera and Ken on Ken.

Thus far, much of what I’ve said isn’t new: Ken has written about his encounters with Dunera boys, and told these stories better than I can. In the time left to me, I give my perspective on what Ken brings to the study of Dunera, and of his methods. I think this is worthwhile. I have the privilege, and it is a privilege, of watching Ken at work, and I reckon I’m one of relatively few to have enjoyed so close a view: Amirah obviously, Jan Brazier on Sacred Places, Jay Winter over the last few years on this project, and probably not too many others.

Dunera scholarship is surprisingly thin for such a rich subject. In 1963, Walter Koenig, a Jesuit priest and one of the oldest men deported on the Dunera, wrote an article for the Catholic journal Twentieth Century about his internment. Two years later Sol Encel wrote about the Dunera internees for the fortnightly magazine Nation, and in 1979 and 1983 Benzion Patkin and Cyril Pearl published histories. Both books have their strengths, while leaving much untold. Klaus Loewald, Ken’s friend in Canberra, contributed two articles to Dunera historiography. Paul Bartrop and Gabrielle Eisen compiled a fine resource book, and a few Dunera boys have penned memoirs, many self-published and some wonderful. Elisabeth Lebensaft and her colleagues have written excellent studies in German of Dunera boys. Leaving aside the articles Ken has published, that’s about the sum of dedicated Dunera scholarship.

Ken takes a broad view of the Dunera story, broader than Patkin and Pearl. He is interested in the lives of the Dunera boys before and after internment. What they did with their freedom is important: think of Klaus Loewald, for example. His dying wish, in 2004, was for a change of government in Australia and in the United States. How could such a telling statement be left out of any account of Loewald’s life?

The trouble with saying more is you need to know more. Ken’s Dunera archive, which includes archival documents, newspaper clippings, interview transcripts, handwritten notes and reams of email correspondence with Dunera boys and their families, fills six large filing cabinets. The first folders in the archive are arranged chronologically and then, if further subdivision is needed, thematically. The Dunera internees were held in camps at Hay and Orange in New South Wales, and Tatura in Victoria. Ken has files for these places, then files on “Camps general,” “Camps – artists and sculptors,” “Camp currency,” “Camp culture,” “Camp poems and songs,” “Camp publications,” “Camps – religion,” “Camps – sex,” “Camps – university exams,” and so on. Another file has information on the use of the term “Dunera boys.” Ever alert to language, Ken asks how and when it arose. Best thinking at the moment is that it emerged in the early 1980s when the film director Ben Lewin was planning his television mini-series about the Dunera.

The second part of the archive is devoted to files on individual Dunera boys. There are about 250 of these files. Some have a few sheets of paper, others half a tree – 2000 pages or more. When I learn something about a Dunera boy, I check the archive to see if Ken has the information already. Usually I find he does, and that he’s made notes on what this Dunera boy had in common with others, whom he was close to, the ways in which his story matters, and where mention of him might fit in the book. Ken’s always one or two steps ahead, but he never makes me feel that I’m one or two steps behind. That’s one reason why he’s a great scholar, and it has nothing to do with reading or writing. He takes people with him.

What then to do with this information? How to distil it into a logical and coherent piece of writing that tells us something we didn’t know? Because Ken’s work is easy to read, readers can assume that the words on the page came to him easily. Not always. Ken proceeds by asking questions, questions that haven’t been asked or answered. Here are three central to his work on Dunera:

What was it about the Dunera boys, and what about Australia, that made so many of them such high achievers in and beyond the academy, the arts and business?

In what ways has the story been mythologised by Dunera boys and others who make it a celebration of worldly success and too readily take the outstanding to be the norm?

Why do some Dunera boys reject comparisons between themselves and asylum seekers, between the Dunera and the Tampa?

Ken is wary of repeating received wisdom. When he was at the University of Melbourne in the 1940s, he wondered if the Dunera boys he knew represented the whole. No, he discovered. On the Dunera were men of different abilities, cultures and religions, a fact that runs counter to popular perception, such as it exists. Brilliant intellectuals were the exception rather than the norm, and a significant minority of the 2000 Dunera boys were not Jewish. Ken has a file on rogues, thugs and scoundrels among the Dunera boys.

The Dunera history we are writing will include biographical sketches of Dunera boys. Some of these Ken has completed. If he’s in contact with the man or his family, Ken sends what he has written for comment, and waits anxiously for reply. Such is his respect for the rules and practice of history, and for people, who are the focus of his work. He takes no liberties, even after a lifetime of good reviews and prizes for writing. And for the record, invariably the replies are positive. Last year Ken published an article about Henry Mayer, who enjoyed a long academic career at the University of Sydney after finishing his studies at Melbourne. He remained a formidable figure, the sort of multifarious and elusive character that biographers find hard to capture. Elaine Mayer, his widow, thought Ken’s piece superb.

The Dunera history will carry the Inglis hallmarks: clear and elegant prose, and sentences that prompt readers to wonder about things they haven’t wondered about before. In terms of the order in which Ken has written his books, the timing is good. To this project he brings all that he knows about the social and cultural history of war, the University of Melbourne, the politics and tenor of postwar Australian society, art and the visual image as historical source, and many other subjects that are part of the Dunera story. And the Dunera history will be the most personal of his books. As Jay has said many times, he and I can help, but the bulk of the story must come from Ken. This history started out as a memoir, after all.

Recently Ken was interviewed by an author interested in the Dunera. She asked what he hoped his Dunera history might achieve. “Fresh thinking” about similarities and differences between the Dunera boys and contemporary refugees and asylum seekers, he answered. A gentle and modest aim, and true to Ken. As he has done over many years, he will show Australians something of their society and invite them to dwell on what they see. •