On picking up a copy of Lauren Samuelsson’s A Matter of Taste: The Australian Women’s Weekly and Its Influence on Australian Food Culture, some eager readers might skip straight to the chapter on baking. Those who do will be greeted by Pamela Clark, the Weekly’s renowned food editor, advising them not to make her own cake.

“Oh. Tip Truck Cake,” she says. “Bitch of a cake. Don’t make it. Unless you are really desperate.”

Clark was speaking to the ABC in 2018 about the Weekly’s most famous cookbook, The Australian Women’s Weekly’s Children’s Birthday Cake Book. I’ve not heard the audio but I assume there was laughter inside her comment. A sense of humour is surely an essential ingredient in baking, especially when it’s for children. For the non-bakers out there: the birthday cake book has been reprinted at least twenty-five times since it was first published in 1980 and has cult status online.

Clark’s advice is lost on me because when my kids were little I was about as likely to make a Tip Truck Cake as I was to acquire an actual tip truck and fly it to the moon and back. Instead I settled for that 1970s classic, the chocolate ripple cake, which is a no-bake, no-shame, never-fail gift to the exhausted single parent. I still reprise it occasionally at Christmas for my grown-up kids. Never had a complaint.

Women’s magazines: my mother never bought them. It wasn’t just that money was always tight, it was because of Mum’s silent rejection of the unattainable ideals dangled about in them. I therefore bring some detachment to my reading of Samuelsson’s book and also to Sue Walker’s biography of her grandfather, The Untold Story of William Shum, published earlier this year. Shum was founding editor of New Idea and Australian Home Beautiful.

Samuelsson makes a convincing case for the ubiquity of the Australian Women’s Weekly, its “omnipresence” in Australian households in its heyday from the 1930s to the 1980s. Circulation peaked in the 1970s at a million a week, with an average of 850,000. Between 1933 and 1982 the magazine published thirty-one cookbooks, and Samuelsson quotes with approval its own claim, made in 1982, that “most families would have sat down to a meal prepared from a Women’s Weekly recipe.”

Not my family. When you work full time, as Mum did, and also have to get dinner for a family of five on the table seven days a week (we never ate out or had takeaway), how can cooking be anything but a chore? At some point in the 1980s, though, Mum found in an op-shop a tatty old copy of a book called The I Hate to Cookbook by the American humourist Peg Bracken, first published in 1960, and fell upon it gleefully.

The book was the result of Bracken and some of her friends having “pooled their ignorance” and tossed together the recipes they “swore by instead of at.” I don’t think we ever cooked from it but Mum and I used to giggle together over recipes for “Stayabed Stew,” “Skid Road Stroganoff” and “Hurry Curry.”

In 1960, when home-making was still thought to be the height of any woman’s ambition (although times were about to change), Bracken’s book was transgressive, and its message a magnificent gift from mother to daughter: that it is perfectly okay not to enjoy cooking. As it happens I do, but if not, so what? Naturally it was Mum who taught me that chocolate ripple cake will do just fine.

I am saddened though that she couldn’t relax and enjoy herself a little with what the Weekly had to offer. Women’s participation in the workforce was rising swiftly in the 1960s and, as Samuelsson notes, the Weekly responded with practical advice. In 1972 it published The Busy Woman’s Cookbook; I wish we’d had a copy of that.

Foundational to the Weekly’s success with food was its famous test kitchen, established in 1934 and enlarged in 1962. The aim was to inspire readers’ trust by triple-testing its recipes before publication. Little knowledge was assumed, so home cooks knew the recipes would work. Samuelsson conducted a survey of 161 Weekly readers and was told by one of them that she “didn’t enjoy cooking” but “wanted to be good at it.”

The magazine’s cookery pages and books were well-produced and illustrated, and the food editors highly trained. I greatly enjoyed reading about these respected professional women, beginning with Margaret Shepherd, appointed in 1933. She was trained in domestic science and nutrition, and her approach, carried on by her successors, was to offer readers practical, nutritious and economical recipes based on the “science” of cooking. From the 1950s the role became more glamourous and there was a shift, as Samuelsson puts it, “away from nutrition towards exhibition” — and to cosmopolitanism and consumerism.

Acknowledging the traditional narrative that the food eaten by Australians before postwar migrants arrived was “boring,” Samuelsson makes a case for the Weekly having promoted “foreign food” to its readers from the 1930s. In reality many of us will remember family food remaining boring until well into the 1970s, but by then interest in many different cuisines, Chinese in particular, was strong. The Weekly’s Chinese Cooking Class Cookbook, published in 1978, has been reprinted fifteen times.

Samuelsson devotes a chapter to the magazine’s obsession with dieting, which began once memories of wartime shortages and rationing had faded in the 1950s. Henceforth, food pages abounded with diet plans, dieting contests, weight charts and real-life weight-loss stories from housewives and celebrities asserting that being slim — attaining the “ideal figure”— would lead to happiness.

Men should consider dieting too, readers were told in 1962. But they were “complete imbeciles” about their health, so it was up to women to keep them at a healthy weight. For men, apparently, weight-loss was about health, but for women it was about appearance.

In her chapter on dinner parties and barbecues, Samuelsson reveals the magazine’s ruminations on male cooking, which amounted to this: Australian men rarely cook. If they do, it’s as a hobby, and they prefer it to involve meat. But when they put their minds to it, they will inevitably be better cooks than women.

Readers might be left seething, but Samuelsson remains calm. She holds her subject in affectionate regard and knows that many of her readers will too. She balances nostalgia with a clear-eyed analysis of the double-standards espoused by the Weekly, and wears her scholarship lightly. The book is beautifully written and illustrated.

Although it is amply referenced, reflecting its origins as a PhD thesis, A Matter of Taste has otherwise been forced on a crash diet and lost much of the contextual discussion I assume it once had concerning other cookery publications in twentieth-century Australia. Margaret Fulton’s bestselling cookbooks, for instance, once jostled for space on the same kitchen benches as the Weekly, but Fulton is mentioned by Samuelsson only in the acknowledgments.

What of the decades-old tradition of community and fund-raising cookbooks that carried on (and still does) despite the Weekly’s “omnipresence” in Australian homes? Samuelsson ignores them. Yet all through this period, stalwarts from countless community organisations, notably the Country Women’s Association, kept churning out their little spiral-bound collections of reader-contributed recipes. If the Weekly can be held responsible for the decline of local culinary traditions, we are not to know.

And then there were rival magazines. Samuelsson mostly avoids them, but New Idea had always been there, established back in 1902 by publisher T. Shaw Fitchett (son of the famous Methodist preacher and writer W.H. Fitchett). New Idea’s first editor, William Shum, spent twenty-three years on the magazine before shifting to another new venture, the Keith Murdoch-owned Australian Home Beautiful, for a further twenty years until his retirement in 1945 (or 1946; two dates are given). Thus, his magazines came into people’s homes every month for forty-three years at a time when, his biographer Sue Walker tells us, “magazines were the most powerful influence on the way people lived.”

Shum was born in Bendigo in 1875, son of a prosperous storekeeper of English and German stock (Schum, originally). Orphaned at fourteen, he and his older sister Ada were taken in by a local family, John and Jennie Harcourt. John was a newspaper proprietor, and after he gave William a job in his business it was clear that the young man had found his métier. He never looked back.

Harcourt sold his business in 1896 and moved with his family, and the young Shums, to Melbourne. Through connections with the Methodist church, William found a job with the Fitchett family publishing business, and in 1905 married Edith Moore, daughter of a prominent Bendigo family. Edith’s brother William Moore became a well-known journalist and art critic, a lifelong friend to William Shum and a regular contributor to Shum’s magazines.

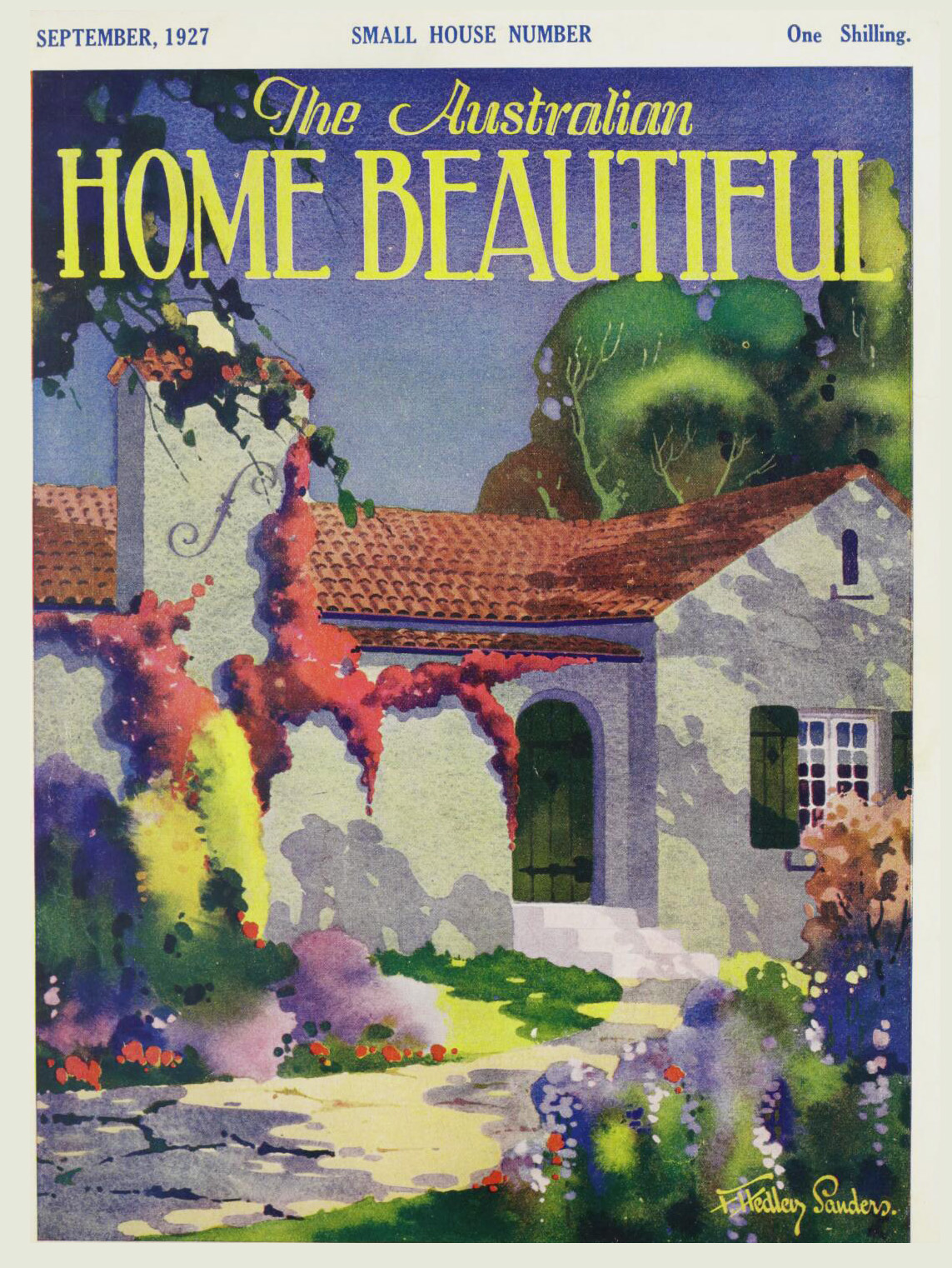

“Home, garden and way of life”: Frank Hedley Sanders’s cover illustration for the September 1927 edition of the Australian Home Beautiful.

Walker devotes about a third of her book to Shum’s antecedents and early years but amid digressions and diversions tends to lose sight of her biographical subject. But she does clearly establish the talents and characteristics that made him a successful editor: his energy, sociability, curiosity and interest in new technologies. He had a wide circle of friends in Melbourne’s literary and artistic circles and was himself a talented amateur photographer.

At home in Brighton Shum would potter about developing his photographs, building furniture and working in his garden. His ideal reader was probably a version of himself, a happy home-maker and family man. He was lucky in his marriage to Edith and was close to his sister Ada, who lived with the Shums all her life. His respect for strong, talented women is reflected in his editorship of New Idea and the staunch support he offered female writers, designers and artists.

By the time we get to Shum’s editorship of Australian Home Beautiful we are well acquainted with the man who would spend twenty glorious years celebrating what Walker describes as “our national spirit and the truly Australian qualities of home, garden and way of life.”

Lovers of interwar architecture and design, like those eager bakers reading Lauren Samuelsson’s book, will likely skip the entrée and mains and go straight to the dessert. Walker (or more precisely, her publisher, The Beagle Press) rewards them with four sumptuously illustrated chapters featuring page after page of reproductions from the magazine, including some heart-meltingly beautiful cover illustrations by artist Frank Hedley Sanders, who contributed to the magazine for fifteen years.

I’m always intrigued, as here, when a publisher spends big on illustrations, design and production but pinches the pennies on copy editing. Hence, Mary “Gilmour” instead of Gilmore, and — even worse — Ruth “Poole Lane” for Ruth Lane Poole.

The book ends abruptly with Shum’s retirement. His life is wrapped up in less than two pages and we learn nothing of his declining years or his death, or anything more about Edith and their children. Nor does Walker deal with the professional struggles and setbacks any editor must face, such as importuning or unreliable authors, tussles with publishers, declining sales, or incursions in the market by rival magazines.

Were magazines the most powerful influence on people’s lives, as Walker claims? What about family, work, healthcare, education, spirituality, politics, the economy? If both authors, Walker and Samuelsson, are inclined to exaggerate the impact of the magazines they write about, there is no denying that magazines did (once) profoundly shape middle-class tastes and aspirations. •

A Matter of Taste: The Australian Women’s Weekly and Its Influence on Australian Food Culture

By Lauren Samuelsson | Monash University Publishing | $39.99 | 240 pages

The Untold Story of William Shum

By Sue Walker | The Beagle Press | $59.95 | 224 pages