Philip Roth: The Biography

By Blake Bailey | W.W. Norton | $65 | 912 pages

Blake Bailey’s biography of the American writer Philip Roth entered the world with all the makings of a scandal — appropriately enough, given its subject became synonymous with outrage over the course of his career. The potential for scandal was amplified by speculation about how the #MeToo movement would have dealt with Roth’s life, which included two torturous marriages, a brace of affairs and a longstanding controversy over his depiction of female characters.

Disclosures made in the biography — of even more affairs, of Roth’s having made a pass at a friend of his one-time stepdaughter, of Roth’s comments about the God-sanctified perfection of a twenty-year age gap between romantic partners — only fuelled the speculation, to the point that Peter Carey, for one, was moved to declare that being “an arsehole” was of no consequence for Roth’s position in the literary firmament.

Roth himself was appalled by the thought that his life might be understood only as a litany of licentious affairs: “It wasn’t just fucked this one, fucked that one, fucked this one,” he said. Responding to #MeToo, he wrote that he had “nothing but sympathy” for the pain felt by women insulted and injured by male sexual desire. “But I am also made anxious,” he told a friend, “by the nature of the tribunal that is adjudicating these charges.” He was “made anxious as a civil libertarian,” he went on, “because there doesn’t seem to be a tribunal. What I see instead is publicised accusation instantly followed by peremptory punishment.”

What Roth would have made of the response to allegations of rape and sexual harassment levelled at Blake Bailey, his chosen biographer and the author of Philip Roth: The Biography, is probably clear. Bailey, who has denied all, has certainly received punishment: his literary agent dropped him; his publisher, W.W. Norton (which faces questions over its handling of the allegations), pulled the book from sale and cut ties with him; and the tide of very positive publicity has decisively turned.

The allegations against Bailey and the controversy around Roth are certainly serious, but they shouldn’t prevent us from paying critical attention to Bailey’s book. It is, after all, an extended and serious study of a significant literary figure. Had it not been for the latest allegations, it would probably be fixed in the public mind as the definitive word on its subject.

The book is also informed by material that may not be available to any future biographer or Roth scholar. As well as marathon interviews with the now-deceased Roth, Bailey was given his subject’s imprimatur to interview more than a hundred classmates, friends, girlfriends, publishers and family members, all of whom appear to have made a considerable effort to help with a book they believed would be authoritative. (One example is the former neighbour of Roth’s who wrote Bailey a hundred-page “remembrance” of her years-long affair with the writer, and was the model for Drenka Balich in Sabbath’s Theater.)

Bailey also had untrammelled access to Roth’s archives at the Library of Congress, as well as papers not integrated into that collection. Among the latter is the infamous “Notes for My Biographer” manuscript that Roth wrote to rebut his former wife Claire Bloom’s memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, and “Notes on a Scandal-Monger,” an account of Roth’s dealings with Ross Miller, an English literature professor who was briefly commissioned to write his authorised biography. (As the title suggests, the arrangement didn’t go well.) The fate of these manuscripts is in the hands of the executors of Roth’s estate, Andrew Wylie and Julia Golier, and there is no guarantee that they will be added to the official archives, let alone survive.

This level of access and cooperation lies behind Bailey’s use of the definite article in the title of his biography; for readers and scholars interested in the dimensions of Roth’s work and his life, these sources mean that this is a book to be reckoned with. No less a figure than Roth himself — who invested considerable time and energy in the process, and who anticipated the book would be substantive, corrective and comprehensive — would have insisted on such a reckoning.

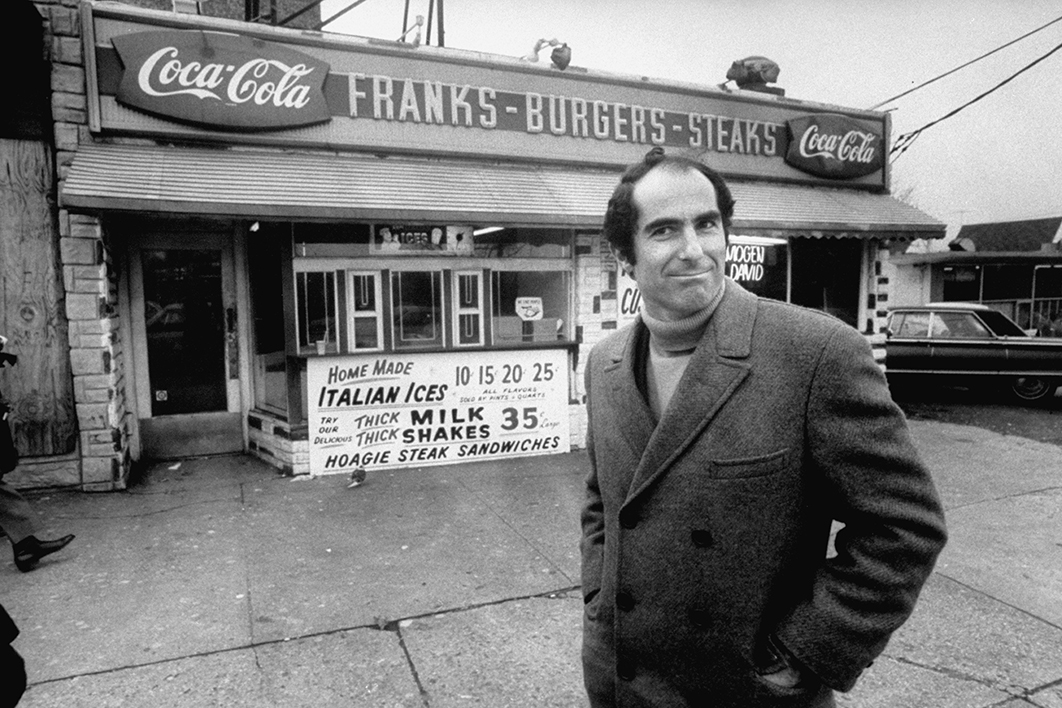

By 2012, Philip Roth had retired from the writing career that had otherwise occupied him full-time since the early 1960s. His journey from prodigal Jewish son to lionised favoured son was complete: he had his own holiday (Philip Roth Day, 23 October) and was acclaimed as one of America’s greatest writers. His books had won nearly every prize it was possible to win and had been anthologised in the Library of America; some of them — Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), American Pastoral (1997) and The Human Stain (2000) in particular — had become classics. His attention was now focused on his biography.

Bailey applied to write the book after the collapse of Roth’s arrangement with Miller. To Roth’s question about why a gentile from Oklahoma should presume to write about him, a Newark Jew, Bailey replied that he was not bisexual, an alcoholic, or possessed of a Puritan family heritage, but he had managed just fine with his well-regarded biographies of writers Richard Yates (2003) and John Cheever (2009). This might well have allayed Roth’s concerns, but what sealed the deal — and wasn’t mentioned in the eventual biography — was Bailey’s unabashed admiration of actress Ali MacGraw, who had starred in the film adaptation of Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus and whose attractions Bailey and Roth cooed over. “Just as important a literary qualification for a biographer as knowing where he fits into the literary continuum with Malamud and Bellow and so forth,” said Bailey later, “is not taking too prim or judgemental a view of a man who had this florid love life.”

Bailey certainly isn’t prim or judgemental. He narrates Roth’s life from promising young author and enfant terrible to titan of American letters in detail and with clarity. Few areas of Roth’s life seem off-limits. “Let the repellent in,” Roth was fond of saying, and Bailey follows that maxim by providing countless examples of Roth’s behaving poorly. Roth nursed grudges, cut people off or used them in his fiction with nary a sign of regret, and was both unconcerned and unrepentant when confronted by their outrage. He was cavalier with girlfriends, seemed impervious to the damage that his chronic infidelity might cause — “God, I’m fond of adultery,” Bailey quotes him saying — and, if anything, was a believer in its benefits: “Adultery makes numerous bad marriages bearable.”

Amid this, as portrayed by Bailey, he was generous and could also be caring. He lent money to friends for medical emergencies and tried to rehabilitate those of them with alcohol problems, he advocated for the provision of libraries, and he championed free expression, no ifs or buts about it.

Bailey constructs his book chronologically and marshals his material effectively. Telling quotes pepper the text, and Bailey willingly allows for conflicting perceptions. One fine example is his citation of Claire Bloom’s thought that Roth’s voice was “suffused with pain” when he “reluctantly” declared his love for her. The reader who has learned of the wounds Roth sustained and inflicted during his first marriage might see the basis of that pain and be more tolerant of Roth’s decision, in the same paragraph, to go ahead with a scheduled trip to the Caribbean, sans Bloom; but the same reader might also understand how Bloom could be disconcerted by the nature of this love and how it is expressed.

Later, Bailey juxtaposes the costs of Roth’s infidelity with the poignancy of his ageing body and his need to charm. While continuing to bed young women, the septuagenarian felt that he had to prepare them for the lurid scars on his body before disrobing. “When lovely Venus lies beside/ Her lord and master Mars/ They mutually profit/ By their scars,” he would sing. Later, he would laugh: “Isn’t it charming? And it gets them. It gets them.”

One of the most notable aspects of the life described by Bailey is the salutary influence Norman Mailer, William Styron and other writers had on Roth and his generation of writers. Having seen the effects of booze and fame, writers like Roth, John Updike and Don DeLillo cultivated a steadiness and discipline that allowed them to be far more productive. Roth was particularly avid on this point. Hurrying to his desk at nine o’clock each morning, he was prone to reprimand himself that the novelist Bernard Malamud would already have been at it for two hours.

Roth was also fond of quoting Flaubert’s maxim that a writer should be orderly and regular in life, like a bourgeois, in order to be wild and original in his or her work. Those habits helped produce twenty-six novels, one novella and a short story collection, a work of narrative non-fiction, an autobiography-cum-novel, and two collections of interviews and essays: a bookshelf and then some.

Bailey also makes the valuable point that Roth and his fellow “abstemious children” began their careers at a time when literature occupied a “sovereign place” in American culture. Today, it is impossible to imagine that a contemporary novel could generate the publicity, notoriety and sheer sales (4.1 million copies and counting) that Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) did — let alone have an immediate social effect, as Portnoy did in Australia. Today’s impecunious scriveners, meanwhile, will gasp to learn that Roth earned US$827,000 from his writing in 1968 alone (and they might faint when Bailey notes that this is equivalent to more than US$6 million today). And those who know the outlines of Roth’s career might well be stricken when they realise that those earnings preceded publication of Roth’s most famous and commercially successful book, Portnoy’s Complaint.

But such detail belies a profound and critical weakness in Philip Roth: The Biography. What should ostensibly draw readers — the work — receives comparatively little attention. Bailey is excellent on Roth’s early career: his faltering short stories, the forays into playwriting, the ignominious and forgotten film criticism, the networks Roth built among emerging critics and contemporary writers. He gives considerable time to the publication process, Roth’s hand in preparing copy (“The masterpiece of an American master,” he ghostwrote of American Pastoral), and the reviews he received (long-time New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani’s reviews are mentioned twenty-one times). But he is often disengaged when it comes to the books.

Unlike the pages of lively and thoughtful analysis that Hermione Lee offers on Tom Stoppard’s plays in her recent biography, Bailey shies away from the works. He is even less concerned about their drafting — a particularly peculiar decision given Roth’s monk-like devotion to writing, revising, and extensive rewriting in response to feedback from a select group of readers. New Yorker editor Veronica Geng became one of those trusted readers and Roth’s favourite editor after talking with him about The Ghost Writer (1979), but Bailey says little about her advice. Ross Miller was presented with a draft of The Counterlife (1986) and told Roth that there was “a good book in here somewhere”: they spent thirteen hours talking about where it might be found. But Bailey betrays no interest in uncovering the effect of this conversation on the published book. Instead, time and time again, he turns back to Roth’s personal life.

This is the point at which Bailey’s refusal to be “too prim or judgemental” counts against him. The sympathy he feels for his subject, necessary for a biographer, is almost certainly too tender, and turns him into an uncritical barracker.

An example of Bailey’s too-close alignment with Roth lies in the book’s treatment of the 1962 symposium at Yeshiva University at which Roth spoke on “the conflict of loyalties in minority writers of fiction.” In The Facts, his autobiography-cum-novel, Roth claims to have been pilloried for his depiction of flawed Jewish characters not only by the largely Jewish student audience but also by the moderator, who asked if he would write the same stories if he were living in Nazi Germany. Bailey cites contemporaneous correspondence largely echoing Roth’s account: by the end, in Bailey’s telling, Roth is “battered,” “dazed,” “overwhelmed” and “wan.” But more recent reportage, using recordings of the symposium, suggests the audience was largely on Roth’s side.

That event was almost certainly important to Roth’s development and career: it even prompted a short-lived declaration that he would never write about Jews again. But to what extent did Roth build it up in his correspondence and then mythologise it in The Facts? This is the question Bailey should have been asking.

More notable, given the controversy over Roth’s “florid love life” and the alleged misogyny of his fiction, is Bailey’s treatment of the women in Roth’s life. As though to prove that he can understand Jewish culture, Bailey dashes his book with Yiddish expressions — most notably shiksa, an often-pejorative term for a non-Jewish woman — and frequently introduces women via their looks before anything else.

Thus, Maggie Martinson — Roth’s first wife, with whom he had a tempestuous, damaging relationship — is both a shiksa and “a short, attractive blonde.” A divorced mother of two children who waited tables to get by, and who may have been molested by her father, Martinson is immediately set up as the opposite of Roth’s “golden child,” and not a page goes by without some aside about her flaws. A request from Martinson that Roth pick up half a pound of parmesan cheese is recalled by Roth and presented by Bailey as a deliberate attempt to distract the writer from his work rather than an everyday errand. Martinson’s threat to kill Roth if he ever slept with her daughter is presented as if it were half-deranged, even though mention has already been made of the clear affection Martinson’s daughter held for him: “Kiss me, Philip,” she once said, “the way you kiss Mother.” The division of the Roths’ assets during their divorce proceedings is presented as evidence of Martinson’s grasping nature, not merely the reality of a divorce.

When Bailey seeks confirmation from Roth for his portrayal of Martinson as forever overreacting, desperate and in some ways physically disfigured, Roth invokes the Brothers Grimm: “This was like some mythological nemesis.” So does this depiction of Martinson amount to a myth, as Roth seems to suggest? Bailey’s answer is no, but Roth would likely suggest otherwise. In The Facts he has his alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, describe this portrayal as unrealistic: “I suspect Josie [Martinson] was both worse and better as a human being than what you’ve portrayed here.” Given his abrupt dismissal of Martinson’s diary — “a pretty insipid piece of writing” — Bailey appears to have had no such suspicions.

In focusing on Roth’s relations with women, Bailey’s sympathy with Roth becomes acute. He joins the fray as an uncritical advocate for his subject. Thus, his portrayal of Roth’s relationship with Claire Bloom works in neither man’s favour. Roth made a pass at a friend of Bloom’s daughter and was rebuffed; he admits to having called her desire to avoid him “pure sexual hysteria.” In response to her claim that he had deliberately goaded and insulted her — “What’s the point of having a pretty girl in the house if you don’t fuck her?” — Bailey makes limp excuses: “His impulse to mock a certain kind of bourgeois piety was among his pronounced traits, both as a writer and a man.” And he seems to make nothing of Roth’s fear, as the #MeToo movement erupted, that this young woman might have more to say about the incident.

What, then, remains of Roth? Notwithstanding its conspicuous weaknesses, what emerges from Philip Roth: The Biography is a striking figure: a man who felt himself compelled to be a writer, who pursued that vocation with unrelenting vigour and abstemiousness — to the point of buying a farmhouse in which he could devote all his waking hours to the page — and who was so diligent in his efforts that he amassed more than 200 boxes of archival material in the course of producing more than thirty books. If he is in need of rehabilitation, those books are likely to be where Roth is rehabilitated. It will not come from a biography. It will certainly not come from this one by Blake Bailey. •