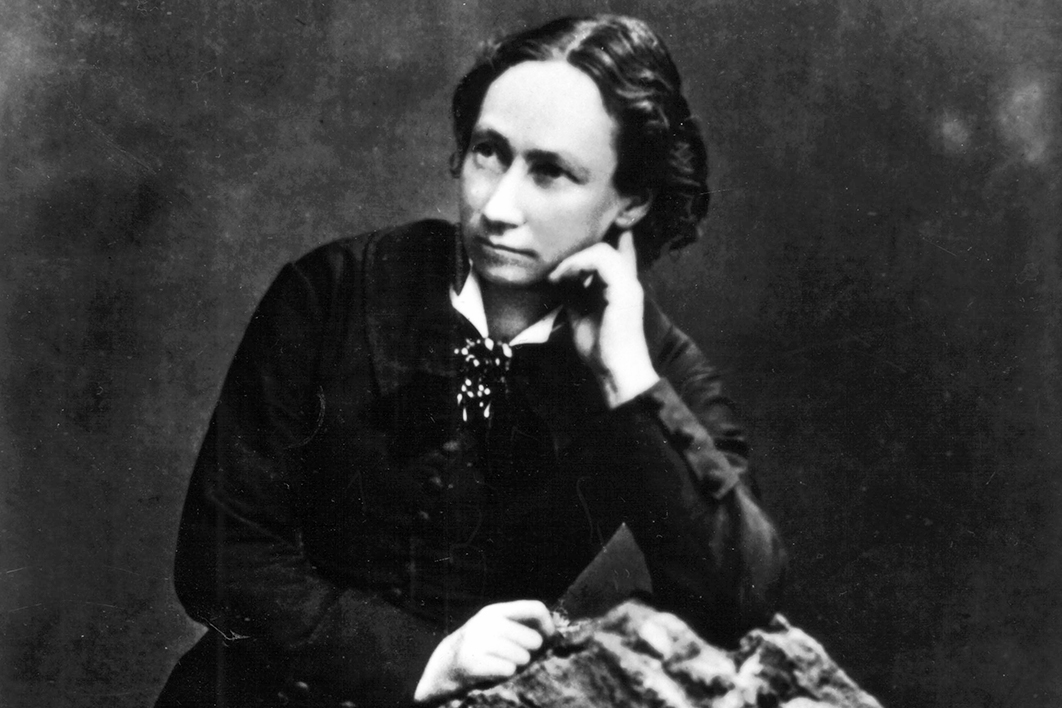

In 1856, fired with republican sympathies, the twenty-six-year-old schoolteacher Louise Michel left her rural home for Paris, where she would teach at Mme Vollier’s school in the 10th arrondissement before opening her own school in Montmartre. The erstwhile Louis-Napoléon, now Napoleon III, had already embarked on his plan for urban renewal, razing the slums to make way for Baron Haussmann’s barricade-proof boulevards. A third of the city’s population was living in abject poverty.

Michel was born at Château de Vroncourt in northeastern France, where her mother worked as a domestic servant and her father was reputedly one of the aristocratic owner’s sons. “I am what is known as a bastard,” she wrote, “but those who bestowed upon me the sorry gift of life did so freely; they loved each other.”

The suffering of Paris’s poorest deepened after Napoleon III declared war on Prussia fourteen years later. As part of her valiant attempt to keep her students fed, Michel joined one of the city’s socialist cooperatives. She was already an ardent feminist, and was delighted to find that socialist men, unlike many of her countrymen, didn’t discriminate against women. “They didn’t define duty according to your sex,” she wrote. “That stupid question was finally done with.”

The Franco-German war ended in ignominious defeat for Napoleon III. Captured on the battlefield, he was forced to take refuge in Britain, leaving Otto von Bismarck’s newly united Germany more powerful than ever.

In Paris, events were moving with a revolution’s rapidity. The Second Republic was overthrown, replaced by a provisional government that surrendered almost immediately and left the ragtag National Guard to defend the capital. When Adolphe Thiers, the first president of the Third Republic, signed an armistice with Bismarck, the socialists seized their moment. The Paris Commune was born.

As government forces attempted to retake the city, Michel threw herself into defending the Commune and became widely known for her fearlessness. At first an ambulancière, caring for the wounded, within a month she was wielding a Remington carbine. When government troops swarmed the city, she fought with characteristic verve. But the government’s response, as vicious as it was disproportionate, resulted in rape, torture and unimaginable slaughter. Eventually the Commune was defeated.

An estimated 35,000 or more Parisians died during the crackdown, far exceeding the deaths in the 1793–94 Terror or the June Days of 1848 as a proportion of the Parisian population. “Shells tore the air, marking the time like a clock,” Michel wrote in her memoirs. Bodies clogged the streets. Many survivors were summarily executed; others awaited imprisonment or worse.

To those around her, Michel seemed totally undaunted. Court-martialled as a prisoner of war, she braced herself for execution. Instead, she was given a civilian trial.

Her demeanour as she conducted her own defence did little to assuage her accusers. “She-wolf” was the mildest of their epithets, and the characterisations were laced with a predictable misogyny. Most damning in their eyes was her “arrogance.” Unmarried, never denying her birth to an unmarried housemaid, “mannish” in her behaviour and careless of her appearance — here was the living antithesis of what conservative Frenchmen demanded of their womenfolk. And an unrepentant socialist at that. Although she denounced capital punishment, Michel approved of violence in the service of justice; facing incarceration and possible deportation, she further confounded the prosecution by stating her preference for death.

She didn’t get her wish. In 1873, along with over 4000 other Communards, Michel was shipped on the frigate Virginie to New Caledonia, the newest of France’s Pacific colonies. Napoleon Bonaparte had initiated penal colonisation earlier in the century, when French convicts were transported to Louisiana. The idea, all too familiar to Australians, was to colonise France’s imperial possessions while getting rid of its indigent and criminal elements. Exile to New Caledonia, otherwise known as Grande Terre, began in 1865, eight years before Michel and her comrades landed in its capital, Noumea.

Largely unknown outside the country of her birth, Louise Michel is today celebrated by the French. It’s not hard to understand why. By any measure, she was a remarkable woman — in a way, a latter-day Jeanne d’Arc.

As I read about Michel in British writer William Atkins’s new book, Exiles: Three Island Journeys, the adjective that repeatedly came to mind was resilient. On the long voyage to her destination Michel was homesick not for Paris but for the France around Vroncourt, where she had grown up. She had loved the wildness of the Haute-Marne countryside and had a particular affinity with its animals. She had been an imaginative, talented child, and in exile would draw on these resources to open herself up to the strange but beautiful land in which she found herself.

“We heard the waves beating eternally on the reefs,” she would write, “and above us we saw the cracked mountain peaks from which torrents of water poured noisily down to the sea during the frequent great rains. At sunset we watched the sun disappear into the sea, and in the valley the twisted white trunks of the niaoulis [the native trees] glowed with a silver phosphorescence.”

It wasn’t only the landscape and the plant life that appealed; she was also interested in the archipelago’s peoples, who called themselves Kanaks, after kanaky, their word for the land. (It was James Cook who named the island group New Caledonia because its largest island reminded him of Scotland. For the French, Kanak became a term of abuse, as it would when it was applied to all indentured Pacific people.)

Prevented from living with the Kanaks as she wished, Michel nonetheless studied their language and traditions and supported their 1878 revolt, advising them on how to sever the telegraph wires the colonials depended on for their counterinsurgency. To the French assertion that they were mere savages, Michel replied that she had always thought herself “savage.” Yet many of her fellow transported Communards took up arms against the rebellion.

In 1880, after seven years in exile, Michel set sail for Europe. Her time in Kanaky had changed her. She had shed her republican sympathies to become a passionate anarchist. Home was no longer a corner of eastern France or even the city from which she had been expelled. In her own mind she was now a global citizen. With borders now meaningless to her, she would travel as often as she could.

She visited Sydney and Melbourne before returning to Europe, where she took up a life of writing, lecturing and political activism, and was reunited with her mother. For centuries London had been a refuge for foreign dissidents, and Michel followed the tradition by spending ten years there. The United States wasn’t as receptive and wouldn’t grant her a visa. Back in France, she had more spells in prison, and was nearly assassinated, but only the thought of being separated from her mother could dampen her indomitable spirit, and only when her mother died did she feel herself adrift rather than free.

Exile: is there a more redolent word? It derives from the old French term essillier — to banish, expel or drive off — but its meaning has expanded to embrace a range of other interpretations. For one thing, it’s a noun as well as a verb, and that alone adds immeasurably to its ambit.

I’ve been thinking about the wealth of literature inspired by exile. In the very beginning — at least in Judeo-Christian mythology — we have those two hapless mortals expelled from Eden by Yahweh. Homer’s Odysseus was a wanderer until he finally made it home. For the Romans the exile was Ulysses. Ovid wrote his most moving poetry living on the Black Sea coast. Only in exile could James Joyce write about Dublin, though it wasn’t the authorities who drove him away but the constrained life in an Ireland still under Britain’s heel and the costive Catholicism of his day. Leopold Bloom, Joyce’s Jewish modern Ulysses, belonged to a group the Romans ousted from their homeland in 70 CE.

And so it goes. There’s displacement, the inevitable result of war and colonisation, and the fate of countless multitudes and source of endless stories. So too migration, generally considered voluntary but often with elements of exile. Exile is a potent term capturing the myriad aspects of our mortal existence. Yet all through Atkins’s Exiles a certain phrase kept coming to me — An exile is occurring. A creature cried in the night, under soft port lights — beating through my brain. I couldn’t remember where I’d read it or why it was so persistent.

William Atkins, whose earlier books, The Moor and The Immeasurable World: Journeys in Desert Places, received wide acclaim for their captivating blend of biography, history and geography, is the best kind of travel writer. He began thinking about Exiles when anti-immigration sentiment in Europe and America was rapidly accelerating in 2016. In the course of exploring the refugees’ flights, he stumbled on the empire connection.

“It occurred to me,” he writes, “that the lives of an earlier kind of displaced person, political deportees sent to a designated location, could show me things that accounts of migrancy, banishment or confinement alone could not: about the word ‘home,’ and the behaviour of empires, and the conflict between leaving and staying that seems to animate the world.”

Not counting his own travels researching the book, he documents three journeys in Exiles — Michel’s transportation to Kanaky, the Russian revolutionary Lev Shternberg’s imprisonment on Sakhalin Island, and the forced exile of Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, the last king of Zululand, on St Helena. All three were being punished for political crimes, but their degree of privation differed, as did the legacy of their experience and how each of them fared when permitted to return home.

Michel, Shternberg and Dinuzulu were nineteenth-century victims of what Atkins calls penal colonialism. This was standard operating procedure for the era’s imperial powers, at least until the cost proved too burdensome, as it did in Australia.

Like Michel, Shternberg returned enriched by exile — indeed, as Atkins writes, “of the exiles I have described none was more elevated by the experience.” Born and raised in Russia’s Jewish Pale of Settlement, and confronted by the tsarist regime’s deep anti-Semitism, Shternberg had been drawn like many Jews to revolutionary socialism. For belonging to a “proscribed organisation” he spent three years in an Odessa prison before being exiled to Sakhalin Island.

Shternberg suffered greatly in both places but equalled Michel in resourcefulness. His studies of the social organisation and traditions of the island’s Nivkh people made a seminal contribution to Russian ethnography, leading to a distinguished academic career in St Petersburg in the years following his release.

Dinuzulu had quite different experiences. The British invaded his homeland in 1871, when he was a boy of ten, sacking his father’s homestead and seizing his cattle. More than a thousand Zulus died during what was a reprisal sortie for the deaths of 1300 British and colonial troops during the Battle of Isandlwana six months before — what Atkins calls “Britain’s greatest military disaster in nearly a century” — at the hands of the Zulu army.

Further assaults in South Africa’s complicated version of the frontier wars had Dinuzulu, now proclaimed king, fighting alongside the Boers to restore his realm and avenge his father’s death. He was captured, tried and convicted of high treason. It was risky to execute him, so the British sent him and members of his retinue to St Helena, Napoleon’s isle of exile.

Although the climate didn’t suit them, Dinuzulu and his party lived in relative comfort compared with Michel and Shternberg. He even assumed the dress of an English gentleman and was given a piano to play. But his withering spirit manifested in an increasingly cranky disposition and a grossly swollen body brought on by a worsening kidney disease. As Atkins writes, “to dictate your enemy’s whereabouts on the planet, as if they were a chess piece, as if they were dust, is to flaunt a frightening and demoralising imperial supremacy.”

Nor was there a home for him to return to. Stripped of both his land and his title, he returned to a Zululand dismantled by the British. His cattle herds were devastated by disease; a hut tax forced his men into wage labour. Yet Dinuzulu himself, deemed a government induna, or tribal headman, and quartered in a house a hundred miles from his ancestral home, was still a king to the Zulu, who continued fighting the British. And so, for the second time, he was convicted of high treason and moved again. “What is grievous to me is to be killed and yet alive,” he wrote to a friend before he died in 1913 of the nephritis he’d developed on St Helena.

“Death in life — the exile’s ubiquitous lament,” writes Atkins. Death stalks the pages of his book. The quashed rebellions and their casualties, the implacable executions, the deaths from disease and starvation, and the body counts of the wars between nations. The life stories Atkins explores all end in death, and as his narratives unfold he alludes at least once to the notion that death itself is exile. Exiles is a beautiful, utterly engrossing book, but by the end of it I was left with a profound sense of the cruelty and suffering that has marked our human existence. Where can it lead, if not to more pain and misery? As the exiled writer Vladimir Nabokov wrote, “Life is beautiful. Life is sad. That’s all you need to know.”

By that time, too, I happened on the source of that quote mentioned earlier in this review — An exile is occurring. A creature cried in the night, under soft port lights. Imagine my disconcerted surprise on discovering it in a novel I’d written myself. “Exile” appears more than once in the surrounding passage, a resounding refrain that describes not a death but a birth, the light that greets the infant, newly expelled from his mother’s womb, glowing in a hospital delivery room. The baby (in this instance, a boy) screws up his face and, as a sign of his robust health, yells his tiny lungs out. And why wouldn’t he? Or any one of us embarking on such a perilous journey? Yet walk the road he will. •

Exiles: Three Island Journeys

By William Atkins | Faber & Faber | $39.99 | 336 pages