Virginia Woolf

By Alexandra Harris | Thames & Hudson | $28.99 | 192 pages

Alexandra Harris is the gifted young English writer who won the 2010 Guardian first book award for Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper, an upbeat account of the English response to modernism through the interwar years. As she tells it, England’s Paris-influenced abstract artists and avowedly “modern” writers turned their attention from the European avant-garde to the English countryside, where they rediscovered the landscape and, using modernist techniques, set about “the imaginative claiming of England.”

Bold Shell Petrol posters of the English countryside by John Piper, Ben Nicholson, Graham Sutherland and Vanessa Bell are among the works Harris uses to illustrate her story. She passes over the fact that these are self-evidently the work of romantics whose modernism was minimal, and ignores their failure to rise to the challenge of Picasso, the most influential modernist through the first half of the century (and the subject of the current Tate Britain exhibition Picasso and Modern British Art).

Of all the works of Alexandra Harris’s English “romantic moderns,” the quintessentially English novels of Virginia Woolf best meet her criteria. Measuring herself against the modernist writers she most admired (Proust, Dostoevsky, Eliot, if not Joyce), Woolf strove for the originality of high modernism in her rendering of experience as romantic impressionism. Her essays, literary criticism and lectures, on the other hand, spoke to the “common reader.” Even so, for many of us, the title of Edward Albee’s 1962 play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, still resonates.

Alexandra Harris wants to allay those fears. Her short new biography, Virginia Woolf, is meant, she says, as “a first port of call for those new to Woolf and as an enticement to read more.” She may have in mind students such as those she is introducing to Woolf as a lecturer at Liverpool University.

Harris’s own first port of call (after she read To the Lighthouse) was Hermione Lee’s magisterial life of Woolf, published in 1996, which Harris says inspired her to study English. Harris writes of being in awe of Lee, and hopes she has “not trespassed too far.” With just 170 pages of text, Harris’s book reduces Woolf’s life and work to ten short chapters – illustrated with rather too many black-and-white photographic portraits of Woolf resembling her mother Julia, the Pre-Raphaelites’ muse. Harris’s interweaving of the strands that made the weft and warp of Woolf’s daily life and her writing life is stylishly minimalist, even if at times it seems to me wrong-headed.

Take, for example, Harris’s commentary on Mrs Dalloway, Woolf’s fourth novel, begun when she was yearning to move back to central London after living quietly in Richmond, on the outskirts of London, for nine years. Her husband Leonard was opposed to the move, fearing that London life would prove too hectic and trigger “the dangerous spiral they had known before.” Alexandra Harris writes:

As he dug his heels in, Virginia felt more trapped. She began to conceive this as a battle for life… She wanted to go “adventuring among human beings” and was “inclined for a plunge.” In the novel she was writing she went on that adventure… Clarissa Dalloway walks out into the streets of London one bright morning and though she is only going to the flower shop, and though she knows the way by heart, she thrills to the excitement of “life; London; this moment of June.”

(This summary does not do justice to the specifics of Woolf’s choreography. It is a blissful early summer’s day in June, 1923. Mrs Dalloway, the wife of a cabinet minister, is walking from her home in Westminster to Bond Street to buy flowers at Mulberry’s the florists – she chooses sweet peas – for her party that evening; the prime minister will be among the guests.)

Harris tells us:

Mrs Dalloway is about a society woman giving a party – a strange subject, perhaps, for someone who dreaded smart society parties. In writing Clarissa, Woolf was thinking partly of the Stephens’ family friend Kitty Maxse, who had symbolised in youth what it meant to be a social success.

Woolf worried (in her diary), writes Harris, that “Clarissa seemed ‘too stiff, too glittering and tinsely’.” But Clarissa is not without self-knowledge, ruefully reflecting: “She knew nothing; no language, no history; she scarcely read a book now, except memoirs in bed…”

What Harris doesn’t point out is that what distinguishes Clarissa from Kitty Maxse is Woolf’s creation of her “stream of consciousness” engaging her with the world around her as she walks:

[A]nd yet to her it was absolutely absorbing; all this; the cabs passing….

Her only gift was knowing people almost by instinct, she thought, walking on… every one remembered… Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street, did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely; all this must go on without her; did she resent it; or did it not become consoling that death ended absolutely? But that somehow in the streets of London, on the ebb and flow of things, here, there, she survived…

These “thoughts on last things” give substance to Mrs Dalloway, society hostess. So does Woolf’s addition of synchronicity to these Londoners’ lives: Mrs Dalloway is walking home with her flowers at the same time as Septimus Warren Smith, a mentally disturbed survivor of the trenches, and Rezia, his Italian wife, are walking to Regent’s Park, to pass the time there before Septimus’s appointment with a psychiatrist in Harley Street.

“In writing Septimus,” Harris says, “Woolf was imaginatively re-entering her own experiences of illness.” Septimus, she says, is “haunted by visions of the trenches.” In fact, what he sees are not images of the trenches. He sees a man emerging from the trees in the park whom he thinks is his dead friend Evans, wearing a grey suit: “no mud was on him; no wounds; he was not changed…” And when Rezia points to a plane skywriting letters above them, Septimus’s ethereal visions are Blakean:

So, thought Septimus, looking up, they are signalling to me. Not indeed in actual words; that is, he could not read the language yet; but it was plain enough, this beauty, this exquisite beauty, and tears filled his eyes as he looked at the smoke words languishing and melting in the sky and bestowing upon him, in their inexhaustible charity and laughing goodness, one shape after another of unimaginable beauty and signalling their intention to provide him, for nothing, for ever, for looking merely, with beauty, more beauty! Tears ran down his cheeks.

… Happily Rezia put her hand with a tremendous weight on his knee so that he was weighted down, transfixed, or the excitement of the elm trees rising and falling, rising and falling with all their leaves alight and the colour thinning and thickening from blue to the green of a hollow wave, like plumes on horses’ heads, feathers on ladies’, so proudly they rose and fell, so superbly, would have sent him mad.

… All taken together meant the birth of a new religion.

Alexandra Harris has nothing to say about Clarissa’s and Septimus’s experiences of the sublime. Her interest lies in what Virginia Woolf shared with Clarissa Dalloway the society hostess: “Though Woolf’s own art form was writing and not the hosting of people in drawing rooms, she generally wanted to be the centre of the crowd,” she writes. “Woolf liked her power to intimidate people, and her power to inspire them.”

HERMIONE Lee’s 772-page biography begins with the admission that there were many times when, yes, she too was afraid of Woolf, of “not being intelligent enough for her,” of “presuming.” After all, Lee was writing the definitive biography for her generation of the great modernist novelist, considered a genius by many of her contemporaries, a writer who was herself a biographer (of Roger Fry), as well as diarist, letter-writer, essayist, memoirist, publisher, lecturer. In Woolf’s private life, there had been her half-brothers’ sexual predations, her relationship with her artist sister Vanessa, her psychotic episodes, her lesbian passions, Bloomsbury. Drawing on her omnivorous reading of everything by and about Woolf, Lee takes the reader into the experiences that, laid down in Woolf’s memory, became the stuff of her literary imagination.

But Lee has so much to tell about Woolf’s hectic daily round that, in the case of Mrs Dalloway, the metaphysical preoccupations of her characters are ignored. Intent on showing how Woolf’s doctors’ treatment of her when she was mad fed into her description of the psychiatrists’ treatment of Septimus Warren Smith, Lee has nothing to say about his hallucinations. Yet what makes his suicide a tragedy is Woolf’s poetic imagining of his exalted visions. Nor does Lee (or Alexandra Harris) comment on the very different belief of sane Mrs Dalloway, a non-believer, in a form of afterlife. As he walks to her party, Clarissa’s first love, Peter Walsh, reflects on her idea that “to know her, or any one, one must seek out the people who completed them: even the places.”

Odd affinities she had with people she had never spoken to, some woman in the street, some man behind a counter – even trees, or barns. It ended in a transcendental theory which, with her horror of death, allowed her to believe, or say that she believed (for all her scepticism), that since our apparitions, the part of us which appears, are so momentary compared with the other, the unseen part of us, which spreads wide, the unseen might survive, be recovered somehow attached to this person or that, or even haunting certain places after death. Perhaps – perhaps.

In the midst of her party Mrs Dalloway learns from one of the guests (the wife of one of Septimus’s two psychiatrists) that a nameless young man has killed himself. Quietly outraged at the talk of death at her party, she slips away to a smaller room where, finding herself alone, her mind is occupied by the young man’s suicide:

He had killed himself – but how? Always her body went through it, when she was told, first, suddenly, of an accident; her dress flamed, her body burnt. He had thrown himself from a window. Up had flashed the ground; through him, blundering, bruising, went the rusty spikes. There he lay with a thud, thud, thud in his brain, and then a suffocation of blackness. So she saw it.

… The clock began striking. The young man had killed himself; but she did not pity him; with the clock striking the hour, one, two, three, she did not pity him, with all this going on… and the words came to her, Fear no more the heat of the sun… She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away while they went on living. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. But she must go back.

When Virginia Woolf committed suicide in December 1941, it was because she feared she was going mad. She had suffered several mental breakdowns during her life, and had made at least one earlier attempt at suicide. Reflecting on Mrs Dalloway, I took heart from Woolf’s account of Septimus’s madness, of Mrs Dalloway’s belief in the power of empathy, and of her joy in London and life itself. I wondered why Harris and Lee did not touch upon the rich inner life from which these individual “streams of consciousness” are drawn.

AT THE end of her book, Hermione Lee tells us that Virginia Woolf’s story is reformulated by each generation:

She takes on the shape of difficult modernist preoccupied with questions of form, or comedian of manners, or neurotic highbrow aesthete, or inventive fantasist, or pernicious snob, or Marxist feminist, or historian of women’s lives, or victim of abuse, or lesbian heroine, or cultural analyst, depending on who is reading her, and when, and in what context.

Alexandra Harris, too, ends her book with an account of Woolf’s rise to pre-eminence as the contested subject of academic literary research: “Politicised, feminised, romanticised, sexualised, castigated, vindicated – the posthumous Virginia Woolf was the figurehead of opposing causes.”

These comments reinforce my impression that academic literary biographers have so many competing academics looking over their shoulders that they diminish the value of their biographies by acknowledging their short shelf life. So let me declare that I am still happy with the first biography of Virginia Woolf, by her nephew Quentin Bell: two slim volumes, written at the urging of Leonard Woolf, published in the early seventies. A talented artist and a fine literary stylist – the author of books on Ruskin and Bloomsbury – Bell declared at the outset that he would steer clear of literary criticism.

His trump card was that he grew up close to Virginia, a member of her and his mother Vanessa’s extended family and of the Bloomsbury group that was their milieu. He was blessed also with a fine sense of the comic – similar, it seems, to his aunt’s. Nothing else can account for Virginia’s taking part (at the age of twenty-eight, before her marriage) in the Dreadnought Hoax, devised by Horace Cole, a friend of her brother Adrian.

Quentin’s account of the hoax, in chapter “1910–June 1912” begins:

On the morning of 10 February 1910, Virginia, with five companions, drove to Paddington Station and took a train to Weymouth. She wore a turban, a fine gold chain hanging to her waist and an embroidered caftan. Her face was black. She sported a very handsome moustache and beard. Of the other members of the party three – Duncan Grant, Anthony Buxton and Guy Ridley – were disguised in much the same way.

Buxton was impersonating the Emperor of Abyssinia; Woolf, Grant and Ridley, members of his court. Adrian played a bearded British interpreter; Cole, a Foreign Office official.

When the train arrived at Weymouth, a flag lieutenant advanced to their carriage door and saluted the Emperor with becoming gravity… There was a barrier to restrain the crowd and the Imperial party proceeded with dignity to where a little steam launch lay in readiness to carry it out to the fleet anchored in the Bay. On H.M.S. Dreadnought… they inspected the Guard of Honour. The Admiral turned to Adrian and asked him to explain the significance of certain uniforms to the Emperor.

“Entaqui, mahai, kustufani,” said Adrian, and then discovered that his stock of Swahili, if it was Swahili, was exhausted. He sought inspiration. It came, and he continued:

“Tahli bussor ahbat tahl aesque miss. Erraema, fleet use….”*

Bell helpfully decodes Adrian’s mangled Latin in a footnote: “‘Talibus orabat talisque miserrima fletus.’ Aeneid iv, 437.”

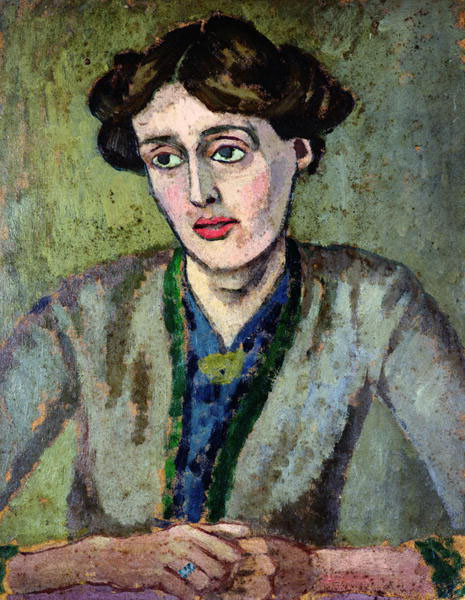

“Prince Sanganya” (above, left) is Virginia Woolf (Virginia Stephen, as she then was). Next to her (left to right) are Duncan Grant, Adrian Stephen (Virginia’s brother), as the translator, Anthony Buxton, Guy Ridley and Horace de Vere Cole, as a Foreign Office attaché.

Having carried off the hoax, and feeling the joke had gone far enough, the fake Abyssinians agreed on secrecy. All except Cole, who alerted the press (and seems to have supplied them with posed photographs of the group), whereupon it became a public scandal. The family was outraged; questions were asked in parliament; and naval officers, their honour impugned, subjected one of the hoaxers (Duncan Grant) to a ritual flogging on Hampstead Heath. Virginia “had entered the Abyssinian adventure for the fun of the thing,” writes Bell, “but she came out of it with a new sense of the brutality and silliness of men.” A century later, only The Chaser would attempt such a politically incorrect hoax (come to think of it, they have). But Nicole Kidman in black face?

Alexandra Harris leaves the Dreadnought Hoax out of her book altogether. In Hermione Lee’s account the humour is lost in the long-winded telling, which ends: “The whole affair seems now like nothing so much as the Marx Brothers impersonating the Russian aviators in A Night at the Circus, Harpo’s long beard coming off as he drinks more and more water in order to avoid making a public speech.”

In case we were laughing, she point outs:

The hoax combined all possible forms of subversion: ridicule of empire, infiltration of the nation’s defences, mockery of bureaucratic procedures, cross-dressing and sexual ambiguity (Adrian and Duncan became lovers at about this time, though the Navy didn’t know that, but the fact that one of the Abyssinians was a woman was the greatest source of indignation).

With its perfectly judged account of the Dreadnought Hoax, Bell’s Virginia Woolf delighted me in the seventies; it also familiarised me with “Bloomsbury”: the circle of friends whose shared lives began in 1905, when the Stephen sisters leased a house in Bloomsbury, near the British Museum, to share with Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, Duncan Grant, John Maynard Keynes and Leonard Woolf, whom they had got to know as the Cambridge friends of their older brother Thoby. Despite their Victorian upbringing, the sisters possessed an “intellectual coolness” equal to that of these brilliant young men, towards whose homosexual love affairs with one another the young women were also “intellectually cool.” (Vanessa was to marry Clive Bell; Virginia married Leonard Woolf after his return from seven years in Ceylon.)

Early on they began to speak of “Bloomsbury”: shorthand for their sense that they were an elite group of avant-garde artists and intellectuals, with shared aesthetics and ethics, owed largely to the Cambridge philosopher G.E. Moore. They valued art and literature, friendship, frankness, sexual freedom, breaking with the past. They valued wit. Whatever their vocation (art critic, biographer, economist, painter, novelist), each was ambitious to “make it new.” As they succeeded, “Bloomsbury” entered common usage. Their close-knit lives, recorded in unbuttoned letters, diaries and memoirs, and those of others they drew into their circle, were also to become the subject of compelling biographies: Michael Holroyd’s Lytton Strachey, Frances Spalding’s Vanessa Bell, R.F. Harrod’s The Life of John Maynard Keynes, Robert Skidelsky’s three-volume John Maynard Keynes, Victoria Glendinning’s Leonard Woolf.

IN Virginia Woolf, Quentin Bell quotes a passage in Woolf’s diary (written when the working title of Mrs Dalloway was The Hours) in which she agonised over her critics’ doubts about her “power of conveying true reality”:

[W]hat do I feel about my writing? – this book, that is, The Hours, if that’s its name? One must write from deep feeling, said Dostoievsky. And do I? Or do I fabricate with words, loving them as I do? No, I think not. In this book I have almost too many ideas. I want to give life and death, sanity and insanity; I want to criticise the social system, and to show it at work, at its most intense. But here I may be posing… Am I writing The Hours from deep emotion? Of course the mad part tries me so much, makes my mind squirt so badly that I can hardly face spending the next weeks at it… But to get further. Have I the power of conveying the true reality? Or do I write essays about myself? Answer these questions as I may, in the uncomplimentary sense, and still there remains this excitement. To get to the bones, now I’m writing fiction again I feel my force glow from me at its fullest.

Virginia Woolf’s last request to her husband Leonard, written on the back of the letter she wrote to him before her suicide, was “Will you destroy all my papers.” He did not, so providing biographers, historians and literary theorists with a wealth of material about Woolf’s crowded daily life at the centre of English culture from the end of the Victorian era through the first four decades of the twentieth century.

Woolf’s fiction is another matter. However much she drew upon her own life, her modernist novels are not essays about herself. Here she struggled to explore, polyphonically, the inner life as only poets had done before. In Mrs Dalloway, Woolf wrote about life and death, sanity and insanity, through the shimmer of thoughts, the stream of consciousness, of Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Warren Smith in a language that is essentially romantic. For her this was “the true reality.” •