It takes a particular kind of person to start a little magazine. Not everyone is cut out for it. You should be high minded and serious. You should have clear ideas about the shabbiness of existing literary culture and the emptiness of dominant intellectual orthodoxies. You should have a near religious belief in the importance of the literary arts, principally poetry and prose fiction. And you should almost certainly possess a strong sense of mission or duty, ideally one driven by a feeling of crisis or embattlement. Without your intervention, literature may not survive.

Most importantly, though, you should have deep pockets. You don’t start a little magazine to make money. Unlike the bigger, glossier titles on newsstands, these barely read journals of literature and criticism operate in an environment of almost perpetual scarcity. Printing costs are high. Circulation is low. There are rarely enough good contributors to fill the pages, nor money enough to pay them. The next grant or subsidy is always in jeopardy, the future always doubtful. Prestige is mostly retrospective. Volunteerism is essential.

Clem Christesen and Stephen Murray-Smith, the parallel subjects of Jim Davidson’s new “dual biography,” Emperors in Lilliput, were just such figures. Both launched an influential little magazine — Meanjin and Overland respectively — and both kept at it for exactly thirty-four years. Both had a deep love of literature and a belief that its cultivation in Australia was a matter of profound national consequence. And both saw it as their duty to help to foster a distinctively Australian literary culture, to bring some life to the “vast cultural Simpson Desert” in which they found themselves in the years after the second world war.

In pursuit of this noble goal, these two enterprising literary missionaries took slightly different approaches. Christesen was an unapologetic elitist. His magazine’s curious title — an Indigenous word meaning “prod” or “spike” derived from the area around Brisbane — was a well-chosen metaphor for his commitment to creating a distinctively Australian literary avant-garde. From its beginnings as an obscure poetry brochure in Brisbane in 1940 to its mature years as an eclectic journal of verse, short fiction and critical essays in postwar Melbourne, this fertile mixture of literary modernism and cultural nationalism was Meanjin’s guiding spirit.

Overland, by contrast, was launched more than a decade later as a kind of literary appendage of the Communist Party of Australia. Many of its early contributors believed that literary modernism was intolerably bourgeois. Instead, they favoured a style of writing called “socialist realism,” one that drew on depictions of working-class experience as a means of advancing the class struggle. Though the magazine eventually broke with the party, freeing its writers to embrace different styles and themes, it always retained this overarching commitment to the promotion of underrepresented voices. At a different time, it might have been called “literature from below.”

Politically, both approaches proved troublesome for their editors. In the 1950s, as the world was slowly divided into competing ideological camps, art and culture emerged as one of the most important battlegrounds for cold war conflict. Across the Western hemisphere, literary production became unavoidably intertwined with political commitment. In Australia — a largely British-derived society that had only recently begun to seriously consider the question of political and cultural independence — this ideological conflict was increasingly entangled in debates over the essential character of the nation.

Both Overland and Meanjin were partisans in this contest, at least in the sense that they were thought to be incubators of a view of Australian politics, culture and history known as “radical nationalism.” In their pages, writers like A.A. Phillips, Russel Ward, Vance Palmer and Ian Turner presented an interpretation of Australian history and culture that was nationalist in outlook and broadly socialist in nature. They fashioned an Australian “tradition,” to use Phillips’s term, that was innately sympathetic to progressive concerns. Overland, the magazine that pursued this line most overtly, even carried the Joseph Furphy-inspired motto “Temper Democratic, Bias Australian.”

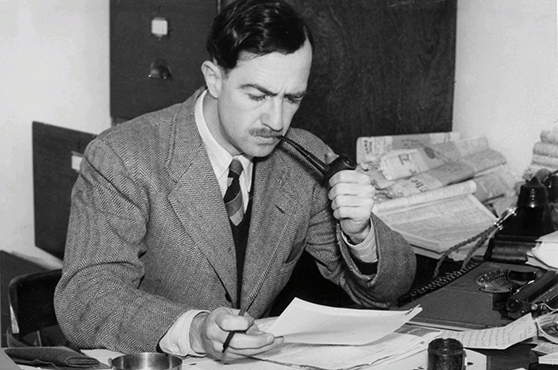

Under siege: Meanjin editor Clem Christesen.

Owing to these left-wing sympathies, both Overland and Meanjin became lightning rods for debates over communist infiltration of Australian society. In 1955, Christesen and his wife Nina were called to testify at the royal commission into espionage. At different points, their support from the Commonwealth Literary Fund was either threatened or denied on political grounds. In 1956, a group of anti-communist intellectuals even launched their own journal, Quadrant, as a deliberate response to what they saw as the dangerous radicalism of these two magazines. In these years, as Susan Lever argued in her account of postwar literary culture, the question of political commitment needed to be considered even by the uncommitted.

In the cold war 1950s, this feeling of embattlement gave both magazines a sense of dynamism and relevance. In the less ideologically fraught politics of the 1960s and 1970s, however, they found this vitality harder to sustain. Neither Christesen nor Murray-Smith were fully comfortable with the political and cultural upheavals of those decades. In the 1970s, in particular, they found themselves up against a self-styled “New Left,” a younger and more diverse group of progressives who were actively hostile to the “gumnutry” and “working-class fairytales” of the Meanjin and Overland school. In some circles, Christesen’s magazine became known as “the Meanjin morgue.”

Most little magazines are principled failures, burning bright before fizzing out. All have a tendency to ossify, hanging around to fight old battles while everyone else moves on. Of the thirty-seven little magazines that were launched in Australia between 1923 and 1954, writes Davidson, just five lasted more than ten issues, and eight produced only one. That both Meanjin and Overland managed to survive was a minor miracle. Meanjin was on annual funding for the entirely of Christesen’s editorship. Overland was printed cheaply, and often held together by a desktop stapler. Murray-Smith called it “a literary magazine that tries to appear quarterly.”

Little magazines have an historical appeal that belies their almost non-existent readership, and as Davidson acknowledges, much of this story has been told before. Over the years, these publications and their illustrious contributors have spawned a small handful of critical studies and group biographies, among them Judith Armstrong’s The Christesen Romance and John McLaren’s Free Radicals of the Left in Postwar Melbourne. Emperors in Lilliput, though, is the most ambitious full-scale profile of the men at the helm of these two legendary publications.

In Davidson’s telling, Christesen emerges as the more complicated figure. He was possessed of an intense editorial zeal. He had Napoleonic ambitions, always fantasising about more pages, more frequent issues, grander contributions. The writer and editor Michael Heyward thought he had a “maniac’s tendency.” Meanjin was his life, and he did whatever he could to keep it going. His personal outlay, too, was immense: by Davidson’s calculations, close to $400,000 in today’s money. For a while he even worked part time as a gardener. All that mattered was the magazine’s continued existence.

Christesen could be difficult, sensitive and “unpleasantly emphatic.” He always seemed to be under siege and on the defensive. At one point, Davidson calls him an “inconsolable child.” He wrote between fifty and sixty complaining letters each week, relentlessly haranguing his contributors, his friends and — sometimes — his enemies about Meanjin and its finances. He was also a perfectionist, demanding impossibly high standards and exercising near total editorial control. He rarely accepted a first submission. At certain points, he rejected close to 95 per cent of manuscripts.

If Christesen was a better editor, writes Davidson, then Murray-Smith was the more interesting man. Overland’s founder was a class traitor, a Toorak-raised, Geelong Grammar–educated blue blood who became a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. He was radicalised first by his war experience in New Guinea, then by the “vast left-wing jamboree” that was the University of Melbourne Labor Club in the 1940s. After several years of loyal service to the party, however, he became one of its most prominent dissenters, resigning his membership in 1958 in protest over the oppressive reality of actually existing socialism.

In comparison with the autocratic editorial arrangements at Meanjin, Davidson calls Overland a “guided democracy.” He depicts Murray-Smith as a kind of literary grandee, an Australian Dr Johnson who seemed like he would be more at home in the eighteenth century than the twentieth. He had an encyclopaedic mind and was a prodigious collector of books (more than 30,000 all up). He was a bit of an eccentric, too, sometimes working in the nude if it was hot. To many, he gave off an impression of lordliness. On the annual Overland expedition to Erith Island in the Bass Strait, he was known as “the emperor.”

For all his radicalism, though, Murray-Smith possessed fundamentally conservative instincts. He tended to fetishise the old and the traditional. He preferred a pipe to cigarettes. He had a lifelong enthusiasm for folk culture and bush ballads, and an abiding interest in remote island communities. As Davidson writes, they were a “surviving example of his romanticised rural ideal.” In the end, this traditionalism put him out of touch with the times. In later life, he waged a bizarre campaign against the adoption of the metric system. At one point he tried writing with a quill. In 1983, he was asked to contribute to the design of a new general education curriculum. His suggestions included Latin, the Bible and “tree recognition.”

By design, a biography of two magazine editors should include some account of the publications into which they poured the majority of their creative energies (if not much of their own writing). For figures as closely associated with their magazines as Christesen and Murray-Smith, it is basically a requirement. The problem facing the biographer, though — even one of Davidson’s pedigree — is that there is no obvious formula for what to include and what to omit: put too much in and you risk obscuring the subjects at the centre of the book; leave too much out and you lose sight of the professional achievement that defined them.

Rather than attempt to resolve this biographical dilemma, Davidson chooses to lean into it. In some chapters he opts for an “all in” approach, embedding a parallel biography of Meanjin and Overland into his two broader biographical narratives. He includes compelling pen portraits of important contributors, gives detailed accounts of key issues of each magazine and discusses many of the significant articles that appeared in them: A.A. Phillips’ famous essay on the cultural cringe, for example, or Ian Turner’s on radical nationalism. The result is not simply a biography of two magazine editors, but a portrait of an entire artistic and intellectual milieu.

This slippage is an important one. Both Christesen and Murray-Smith were decent writers, but neither possessed a particular talent for poetry or prose. Christesen’s published output amounted to a catalogue of Meanjin editorials and a small handful of poetry collections. Murray-Smith, more of a collector than a writer, produced a dictionary of Australian quotations and a guide to English usage. Yet their invisible editorial hands were behind some of the best Australian writing and criticism of the mid-twentieth century. Their talent, so to speak, was to foster talent. As Christesen once joked, self-deprecatingly, he was “a kind of untutored literary midwife.”

It is these unique characteristics that necessitate the book’s rather uneven narrative. Emperors in Lilliput contains two explicitly biographical chapters, two that tell the story of the magazines themselves, a concurrent account of the 1960s and a broader, themed chapter on the difficulties of little magazine publishing. Towards the end, Davidson even switches to the first-person in order to tell the story of Christesen’s departure from Meanjin. The book closes then with a long and richly detailed portrait of Murray-Smith in his twilight years, while Christesen disappears from the narrative entirely.

This omission, I suspect, is at least in part due to Davidson’s own role in the Meanjin story, an immensely important detail which, to his credit, he describes frankly. Davidson was Christesen’s successor at Meanjin, but we learn in a fascinating late chapter that the handover was an acrimonious one, a “power struggle in the Clemlin” that left both sides permanently embittered. Davidson confesses that for many years he could not even look at the old Christesen-edited Meanjins. For him, they were “radioactive.” The whole book, he says, was in some ways an attempt to exorcise these demons, to get a sense of Christesen beyond his own personal enmity.

He has done an excellent job. Emperors in Lilliput is a detailed, colourful and highly entertaining portrait of Australian literary life in the postwar years. Reading it, it is hard not to be nostalgic for this ostensible golden age of literary fertility. For all the shortcomings of these magazines — not least their overwhelming maleness — they were reflective of a time when poetry, fiction and criticism seemed to matter, or at least to possess an exalted status. This was a period when intellectually minded Australians really believed in the literary arts, not only as a means to a fulfilling interior life, but as a crucial part of the development and vitality of the nation itself.

Not so today. As Davidson laments in a plaintive afterword, even among the artistically inclined, poetry, fiction and literary criticism are no longer held in such high esteem. Beginning in the 1970s, they were usurped by cinema, the performing arts and other forms of media. Literature, he says, has itself become performative. These days, our intellectual infrastructure includes podcasts, writers’ festivals and — God help us — Twitter. Literary magazine culture still exists, but it can feel slightly old-fashioned, like the two pipe-smoking men on the cover of Davidson’s book.

This doesn’t mean we should throw in the towel. Popularity does not necessarily equate to influence, and economic return is no proxy for value. Times change, media technology evolves, tastes shift, but the impulse to describe the world, to capture and make sense of it, remains. Meanjin and Overland, after all, are still going. HEAT, Southerly and the Sydney Review of Books march on, while serious international journals like The Baffler and n+1 are now only a click away. In the age of the smartphone, the vast cultural Simpson Desert can appear more like a rainforest.

Launching a small circulation, serious-minded journal of literature and criticism — or some online version of it — is still as crazy as it ever was, especially in this country. You will still be scrapping for money and contributors, and you will still be working long unpaid hours. There will likely be little reward in this world. Thanks to your intervention, though, literature might just survive. •

Emperors in Lilliput: Clem Christesen of Meanjin and Stephen Murray-Smith of Overland

By Jim Davidson | The Miegunyah Press | $59.99 | 480 pages