AROUND a decade ago, ABC Radio National’s Arts Today ran a feature on Tasmania called “Essence of Place.” “Tassie,” said the promotional blurb, is “sometimes completely left off maps… But mainlanders neglect it at their peril because this is a land of stimulating contrasts and, like a canary in the coal mine, often acts as an indicator of things environmental, political and social.” Guests on the program included the late Tasmanian poet, humanities academic and Good News Week star Margaret Scott. A sparkling raconteuse, Scott recounted her “unique Jelly Bag Theory, which is that the national experience drips down in a concentrated form into Tasmania.”

Ten years on it’s a good time to have another look at what’s come out of Scott’s old-style jelly bag, not only to see where Tasmania is heading but also to check whether it offers fresh insights into the national condition.

First, to forests, the issue with which Tasmania is most often identified in the national imagination. The Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement, championed by the state Labor government and its federal counterpart, recently hit what may prove to be insurmountable obstacles. At the end of March, Jonathan West, of the Hobart-based Australian Innovation Research Centre, released his summary of the findings of a five-month inquiry by the Independent Verification Group, or IVG, which he heads. The inquiry’s job was to verify the conservation values of 572,o00 hectares of native forests nominated under the agreement and assess their compatibility with the forestry industry’s sustainable wood supply requirements. West’s fellow IVG members were natural resource management and forestry industry expert Robert Smith, natural resource social scientist Michael Lockwood, Brendan Mackey of ANU’s Fenner School of Environment and Society, ecologist and risk analyst Mark Burgman, and geologist Ross Large.

In a nutshell (and it’s a hefty nut: the report proper ran to an encyclopaedic 2500 pages), the IVG outlined a nine-point plan for compromise between the entrenched positions of environmentalists and foresty industry representatives, including maximising the potential for private investment in the sector. The group found that Forestry Tasmania has been harvesting native forests at double the sustainable yield; that existing contracts need to be reduced through negotiations to restore sustainability to the native forest industry; and that environmentalists must accept some logging in the forest areas they want protected.

To those on the fringes of the forestry debate — in Tasmania it’s almost impossible to be a complete “outsider” on this question — it looked like a reasonable, workable compromise to end a fight that’s divided Tasmanians for decades. No one has presented a detailed, considered and fully costed alternative to the IVG framework, setting out an economically plausible future for the industry. But rusted-on combatants on both sides of the forest dispute — timber industries on one side, environmental groups on the other — thought otherwise, and West became the high-profile target of a round of personal attacks seeking to undermine the IVG’s findings.

West was accused of bias against forestry because many years ago he was a director of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society for a short period. Never mind his many subsequent years at Harvard Business School and beyond, and never mind that the current negotiations are not, in fact, focused on wilderness as it used to be understood. West was also alleged to be biased against Tasmania’s natural environment because he “supports a pulp mill and mining in high conservation forests, because he is also on the board of a major supplier to the mining industry,” and, according to the Tasmanian Times North blog, “could also be trying to shut-down the Tamar Valley olive industry to assist his massive Murray Valley olive production company…”

Could someone standing in West’s shoes actually “win” in Tasmania’s forestry fights at the moment? The short answer is probably no. But that response may be too hasty. Soon after the release of West’s summary of the IVG findings and discussion of this topic on ABC1’s Q&A, I fielded a request to talk about forestry politics from two Tasmanian men with deep personal and professional investments in the outcome of the dispute. One was a timber industry investor, supplier and employer; the other, an office-holder in a prominent environmental group. Social acquaintances for over a decade in the small community we all share, they’d realised that they largely agreed on a shared strategy for transitioning Tasmania’s forestry practices into industry options that are more economically viable, environmentally sustainable and socially palatable.

Both men despaired of the current state of public debate on these questions. Together they asked me for practical help, pointing to the “peace polls” in Northern Ireland, conducted by Colin Irwin of the University of Liverpool and Queen’s University Belfast in collaboration with the political parties elected to take part in the Stormont talks. An iterative series of public opinion surveys, the “peace polls” improved transparency, inclusiveness and public confidence in the prospect of ending the Northern Ireland conflict, shifting language and moving minds. It’s time, my clearly distressed but determined visitors claimed, for something along these lines in Tasmania.

Their call is timely, given the pitch and prejudices of our political culture, in Tasmania and nationally. There’s a worrying common thread running through the criticism of Jonathan West’s CV and the hyperscrutiny of Julia Gillard’s wardrobe by everyone from Germaine Greer to Tony Abbott. Many of us might not fancy the contents of either, but it’s a distraction from the urgent issues.

To her credit, Jane Calvert of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union called for the personal attacks on West to stop. “It does no good to tear strips off people because you don’t agree with what they say,” she is reported to have said. “Play the ball not the man.” It’s a shame that Calvert’s message didn’t fully register with fellow trade unionist Paul Howes, Labor Party powerbroker and secretary of the Australian Workers’ Union. On a recent fly-in-fly-out visit to Hobart, Howes called for Tasmania to stand up to the environmental movement for the sake of the state’s future, warning that its opposition to the proposed Gunns pulp mill in the Tamar Valley is bound to translate into threats to the aquaculture industry as well. Howes told Tasmanians to “muscle up” and give “the middle finger” to mainlanders meddling on the pulp mill and other issues, especially those from the eastern suburbs of Sydney.

On one reading that’s a cheapish dog whistle designed to criticise high-profile players in this debate — people like Sydney-based businessman Geoffrey Cousins, an outspoken opponent of the pulp mill. It’s also startlingly reminiscent of the message delivered by John Howard to 2000 forestry workers in Launceston on the eve of the 2004 federal election. And it overlooks the fairly glaring fact that Howes lives in… well, Sydney, actually.

A while back, Sydney was also the home of Peter Whish-Wilson, the newly anointed replacement in the Senate for retiring Greens leader Bob Brown. Unlike Jonathan West, Whish-Wilson does have a tangible bias in the field of Tasmania’s contemporary forestry conflict. A Tasmanian resident since 2004 and currently an owner of Three Wishes Vineyard on the banks of the Tamar Valley, he has actively campaigned against the proposed pulp mill and ran on exactly that platform for the Greens in elections for Tasmania’s upper house in 2009 and for the Senate in 2010.

Once he was fingered as a likely successor to Brown, though, mainstream commentators, mainlanders mainly, began working hard to drive a wedge between the two senators by painting Whish-Wilson into a “light green” corner, presumably a place with less appeal for the Greens’ more traditional, activist-oriented supporter base. Given the catchcry that the Greens are anti–big-end-of-towners, it was surprising that analysts made nothing very substantial of Whish-Wilson’s professional experience working in equity capital for Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank in places like New York, Hong Kong, Melbourne and Sydney. They also largely left unexamined the curriculum content he’s delivering in the School of Economics and Finance at the University of Tasmania, including what’s said to be the world’s first environmental finance course. A better tagline to attach to Whish-Wilson might have been “bright green.”

If choosing someone like Whish-Wilson is indeed part of rebranding the Greens as a party, it seems unlikely to alienate rusted-on Greens voters in significant numbers. It could even pull across more of the disaffected from both the Labor and Liberal camps, whose leaderships have noticeably lost connection with chunks of their own heartland constituencies. Parties with dramatically declining and ageing memberships, and a growing cadre of parliamentary advisers and aspirants with few visible beliefs, are unlikely to attract and hold latent Greens voters.

LIKE Brown, and like those men who came to my office (and unlike Howes, in this case), Whish-Wilson has a big personal stake in the issues he’s prosecuted politically. In the 1980s, Brown gained public purchase by being arrested, assaulted and shot at in now-iconic protest actions against flooding the Franklin and logging Farmhouse Creek. Twenty years younger than Brown, Whish-Wilson has relocated a sizeable chunk of his financial capital, his family and his career onto Tasmanian land — no small investment. He’s surfing a New Tasmanian wave that today features even fresher arrivals and returnees, lured by the notion that Tasmania is an optimal testbed for a niche range of clever cultural and economic initiatives. Which brings us to the broader, and changing, state of Tasmania’s economic and social makeup.

At its best, the small scale of Tasmanian society means it’s relatively easy here to connect across all kind of divides that keep mainlanders more huddled in educational, occupational and ethnic “ghettos.” Tasmania can function like a salon, lending itself unusually well to interdisciplinary conversations and collaborations across familiar and established divides. That quality has long nurtured rich clusters of creative types that Richard Florida (best known for his book The Rise of the Creative Class) would die for, and was recently picked up in the trend-spotting international magazine Monocle.

Among these newer entrepreneurial thinkers are social researcher and author Ross Honeywill, now living in Hobart, who for some time has mapped a trend driven by “the four million Australians and fifty-nine million Americans” who, he estimates, “value experiences that directly touch the human mind and feed the human spirit... who spend more, earn more, read more, know more, and are better educated.” Another relatively recent arrival is Sydney restaurant critic Matthew “Gourmet Farmer” Evans, who farms a small landholding in the Huon Valley, further south. Back in town, Sri Lankan–born New Yorker Varuni Kulasekera has opened a remarkable tea emporium near the headquarters of Arts Tasmania, and the glowingly gonged Garagistes wine-bar-and-diner team of Luke Burgess, Katrina Birchmeier and Kirk Richardson serve fare of distinctively Tasmanian provenance on the site of an old inner-city garage.

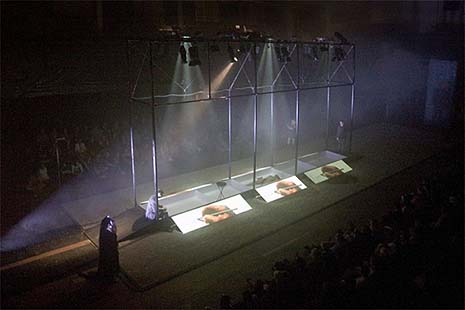

They’ve joined longer-embedded Tasmanians like former antiques trader Penny Clive, whose art foundation Detached, housed in a heritage church in Hobart, is complemented by an impressive high-end dining venture she runs with her funds manager husband Bruce Neill at Peppermint Bay on the D’Entrecasteaux Channel. More blockbusting are the efforts of gambler David Walsh, who’s invested around $180 million to build and service the increasingly internationally famous Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart’s northern suburbs. There’s also a companion music festival called MONA FOMA (curated by ex–Violent Femmes bass player Brian Ritchie, who originally hails from Wisconsin), which recently included a commissioned work called The Barbarians, an immersive opera by Hobart composer Constantine Koukias with an award-winning set designed by local multidisciplinary design practice Liminal Studio. This summer also saw the arrival of a seasonal, sustainability-focused community market called MoMa on the museum’s roof, featuring Tasmanian craft, design, produce, food, wine and music, all housed in a Minnie Mouse snake monster tent by New York Artist Daphane Park (the brainchild of David Walsh’s partner Kirsha Kaechele, an art curator born in California and raised in Guam).

Increasingly, the MONA juggernaut is credited locally as one of the best human-made things Tasmania has going for it right now — partly because it attracts tourist dollars to the state’s sagging economy, partly because it’s already inspiring a range of smaller-scale spin-off ventures, and partly because it’s no drain on the public purse at a time of severe budget constraints.

That last point is increasingly pertinent. The scope of MONA’s potential ongoing activities hinges quite dramatically on the size of the back-tax bill the Australian Taxation Office may or may not deliver to the reclusive Zeljko Ranogajec, another Tasmanian gambler who’s generously backed Walsh’s bankrolling of MONA. If the ATO claws back, say, tens of millions of dollars or more, where might that leave MONA and the evident public good it delivers to Tasmania? Would or could the state government pick up a shortfall at a time when it’s struggling to maintain baseline funding for schools, hospitals and policing — and when the Liberal opposition has hammered it on all those bread-and-butter fronts, throwing in promises to axe the office of the State Architect and halve public funding to Tasmania’s Ten Days on the Island arts festival? And would any federal government come to the party at a time of increasing strain across the Commonwealth about the fairness of current GST distribution, persistent complaints by mining-rich states like Western Australia that it unfairly props up its “mendicant” southern cousin, and signs from opposition leader Tony Abbott that in government he’d at least contemplate cutting up to $700 per annum in GST revenue from the state?

Right now, Tasmania does need a real circuit-breaker, if not a game-changer. If we can’t yet strike a better deal on forests, giving MONA a fair break would be a sensible start. •

Natasha Cica is Director of the Inglis Clark Centre for Civil Society at the University of Tasmania and a Sidney Myer Creative Fellow. Her latest book is Pedder Dreaming: Olegas Truchanas and a Lost Tasmanian Wilderness.