If Monte Punshon is remembered today, it is for two things: she lived to 106 and in her last years she was feted as “the world’s oldest lesbian.” This woman — born a century earlier but happy to declare in the 1980s that she had always loved women — had always resisted the label. For her, unlike the lesbian feminists of a new era, the personal was not political: “I’m not labelled anything. I’m just me myself. I hate that name.”

Tessa Morris-Suzuki’s biography of this intriguing figure, A Secretive Century: Monte Punshon’s Australia, takes as its inspiration “a new wave of biography and microhistory writing that sees the exploration of individual lives as a vantage point” for scrutinising and challenging established versions of history and thus making “forgotten histories visible.” The key to her approach lies in the book’s title, and her subject’s long and varied life provides the opportunity to examine the byways of Australian history from the late nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth. Punshon’s life as a devotee of Japanese culture also gives Morris-Suzuki, a distinguished scholar of East Asian and Pacific History, scope to use her expertise.

Much of the author’s material derives from a memoir by Punshon herself. Encouraged by her Japanese friends and aided by former diplomat Warren Reid, Punshon recorded her recollections after she entered her eleventh decade. Under the title Monte-San, with two subtitles, The Time Between and Life Lies Hidden, the memoir was published by the Kobe Japan–Australia Society. Morris-Suzuki scrutinises it carefully, correcting for errors of memory and exploring the persona Punshon created in her narrative and the elements of her life she chose not to reveal.

Life Lies Hidden may have been Punshon’s original title, and would perhaps have been a more suitable one. Far from attempting a confessional memoir of the kind now popular, Punshon “treasured her privacy,” writes Morris-Suzuki, “even as she embraced the limelight” thrust upon her in her old age. A woman with a multiplicity of identities, she became at various points in her life Miss Montague, Monte, Mickey and Erica Morley Punshon.

By the time Ethel May Punshon was born in Ballarat in 1882, the Victorian town had been transformed from a wild collection of goldfields shanties to a prosperous provincial centre with impressive architecture, wide streets and horse-drawn Cobb & Co coaches. Her family was solidly middle-class and Methodist, and for the first eleven years of her life, until the birth of a sister, she was an only child.

After the family moved to the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, Punshon shifted to the front of the classroom; by the age of fifteen was teaching a large class of five-year-olds. But theatre was her first love. Although her respectable family would not have condoned her desire to be a professional actress, she performed in amateur theatricals and travelling children’s theatre as Miss Montague.

Despite a stint in radio broadcasting, though, teaching remained her mainstay throughout her life, with inner-suburban, bohemian St Kilda her preferred Melbourne base. Mingling with artists, writers and theatrical people, she also frequented the Café Australia’s Walter and Marion Griffin–designed tea lounge that had opened in the city in 1916.

Punshon’s love affair with Japan began with her first trip there in 1929, the lucky result of being chosen as the travelling companion of a friend who had won a first class return trip. She went on to visit Korea alone. As Morris-Suzuki writes, Australian attitudes towards the region have alternated between Good Asia and Bad Asia over the decades:

Good Asia was pleasingly exotic, full of picturesque costumes and intriguing rituals… Bad Asia was violent, incomprehensible and menacing… [S]erious journalism and political analysis at this time tended to depict Japan as “Good Asia.”

These depictions would be dramatically reversed in the late 1930s. But what strikes Morris-Suzuki is the new visitor’s ability to go beyond one-dimensional oversimplification on her 1929 trip.

Punshon would make several more trips to Japan during her lifetime, the last as the “roving ambassador” for Expo 88 in the final year of her life. She would also go on to take Japanese-language evening classes at the University of Melbourne, which introduced her to a new group of friends. During the war, when Japan was Australia’s enemy, she was appointed as a warden at the Tatura Internment Camp in inland Victoria in 1942 and discovered that one of the internees was her beloved former Japanese teacher, Mowsey Inagaki.

Monte Punshon continued to take on new challenges and in 1948 accepted a temporary teaching position at the Bonegilla migrant reception centre in northeast Victoria. In 1952, she boarded a Qantas seaplane bound for Noumea and then flew onwards to Port Vila, the capital of the Anglo-French condominium of the New Hebrides (now independent Vanuatu) where she would work for a year as teacher in charge of the Port Vila British School. In spite of the position’s grand title, the school barely existed and Punshon, by then in her seventies, took the opportunity of the relaxed atmosphere to organise a sports day and stage a Christmas play with the children of the British settlers.

A Secretive Century adds little about Punshon’s sexuality and love life to what was revealed in the pioneering work of historian Ruth Ford in the 1980s and in Margaret Bradstock and Louise Wakeling’s anthology of lesbian life stories, Words from the Same Heart. Punshon’s own reticence about the part of her life that had been necessarily shrouded in secrecy for most of her adulthood is understandable. For those of us who identify with the queer community, “coming out” is still a contingent position that may need to be reconsidered in particular situations.

Morris-Suzuki does uncover a little more about the woman Punshon described as the “love of her life,” Debbie, with whom she lived in the 1920s. Debbie Sutton was married when the two met, though she was divorced by her husband after he returned from war service. Her relationship with Punshon started to fray when Sutton became involved in Christian Science and trained as a practitioner. She moved in with another woman, also a Christian Scientist, but died of tuberculosis in 1931.

One of A Secretive Century’s great strengths lies in Morris-Suzuki’s forensic probing of how an Australian woman of English heritage discovered much of her life’s meaning in East Asia rather than by identifying with the British Isles and Europe. The book’s cover features an image based on one of those collected by Punshon in her scrapbooks of women defying gender conventions. Curiously, though, it is a 1928 portrait by British artist Laura Knight of a tweedy young Englishwoman with an Eton crop holding a rifle who looks for all the world as if she is about to go duck shooting.

Morris-Suzuki’s microhistorical approach to biography can at times present a challenge to readers like me who might follow biographer Hermione Lee’s approach: “Whether we think of biography as more like history or more like fiction, what we want from it is a vivid sense of the person.” There are occasions when the focus on Punshon recedes and she seems to become something of a conduit for the author’s political and geographical analysis of Australia’s relationship with Asia and the Pacific throughout a complex century.

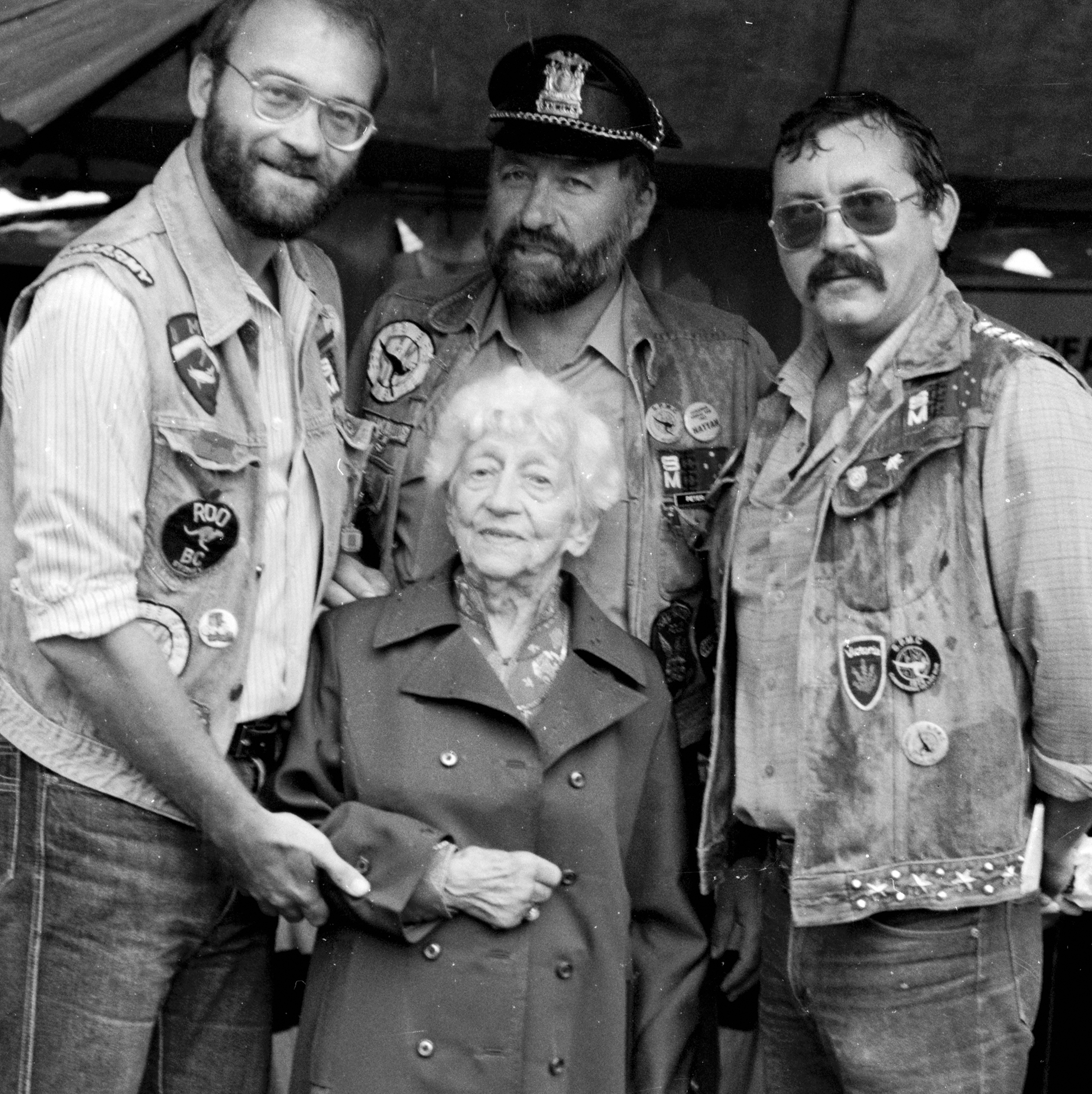

But that focus returns vividly and poignantly to Monte Punshon in the last decade of her life as she enjoys the attention of her lesbian activist friends and “homosexual boyfriends,” going with them to the theatre to see plays like Torch Song Trilogy and drinking one too many glasses of Cointreau at the theatre bar while she would “enthral — or even startle — her young companions with her flirtatious comments and her intimate revelations about past loves.” A new intense friendship developed over these last years with Margaret Taylor, a trained nurse many decades her junior, who took an ailing Punshon into her own apartment in her final months and was there on 4 August 1989 when Monte “died peacefully in her hospital bed.” •

A Secretive Century: Monte Punshon’s Australia

By Tessa Morris-Suzuki | Melbourne University Press | $35 | 330 pages