Jules Feiffer is an all-but-forgotten name today but his influence is discernible in every contemporary comedy of anxiety, whether on the stage, in the cinema or (especially) on television. Seinfeld, Frazier, My Family, Two and a Half Men, How I Met Your Mother and a host of similar programs owe a sizeable debt to the weekly cartoon strip Feiffer drew for the Village Voice in New York from 1956 to 1998. He was also a playwright (Little Murders, Elliot Loves), a novelist (Harry, the Rat with Women) and a screenwriter (Carnal Knowledge, Popeye). Along with other dimly recalled figures connected with the stage, the nightclub and the off-Broadway review — the comedians Mort Sahl and Shelley Berman and the improvisers Mike Nichols and Elaine May among them — he discovered that urban angst was the modern comic mother lode.

Indeed, Feiffer claims to have invented the Jewish Mother Joke, and one variant of it from the Village Voice is a good introduction to his work for anyone unfamiliar with it. It is a strip cartoon in which the panels show only the face of the mother in question, a face redrawn ten times over with small variations in expression. As is customary in Feiffer’s cartoons the drawing is balanced, at first glance over-toppled, by a substantial text, here nearly 200 words — so many that one might think that it was in the words that all the work was being done. The penultimate panel upsets any such idea. There the mother’s eyes engage silently with our eyes, as we weigh up the implications of all that has been said.

One of Feiffer’s variants on the Jewish Mother Joke, which he might have invented.

The subtle changes from one drawing to the next — “moment-to-moment” rather than “action-to-action” transitions — draw our attention to character, mood, motive and predicament rather than to situation, deed, narrative and comic payoff: in fact there is a payoff, and a good one too. But, as so often in Feiffer’s work, instead of dismissing us into laughter it invites us into thought.

Feiffer must have drawn nearly two and a half thousand cartoons like this, more if one counts his work for other publications like Playboy, the Observer — Feiffer had an early success in London — and latterly the New York Times. But his heyday was undoubtedly the ten years between the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s. It was then that he refined his peculiar mixture of angst and kvetch, material that now discloses itself as the negative space, the psychic dark energy, of America’s affluence, self-confidence and hegemony over its half of a bi-polar world.

He covered everything: male inadequacy, the pretensions of modern dance, the battle of the sexes (pre-feminism), the bomb, the new narcissism, the organisation man, psychosomatic stomach aches, phoney Village bohemianism, through a series of dramatic monologues in which the speaker arrived at a much worse position than where he or she started. These confessional strips were first collected in the bestselling Sick, Sick, Sick (1959) — a phrase that described not Feiffer’s kind of humour, but the people he depicted, and the society that produced them.

Backing into Forward is Feiffer’s lively, funny, fresh, frank, informal memoir, comprehensively illustrated, and beautifully produced in the manner of the best American publishing — an inviting dust-jacket, stylish but restrained layout, elegant typeface, high-quality paper, deckled edging, copious illustrations, a credit to the Nan Talese imprint from Doubleday. Feiffer deftly switches his attention back and forth from life to times to career and one of the book’s many virtues is the way the author helps us grasp the ceaselessly alternating flow between all three.

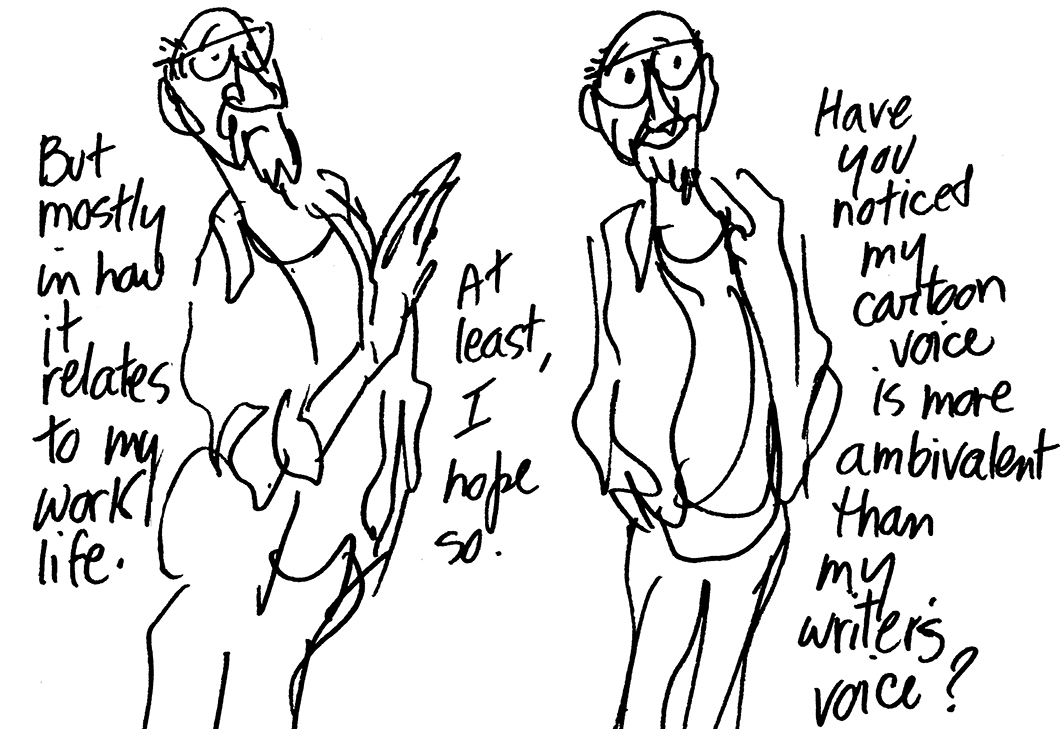

Backing into Forward also reminds us on every page that Feiffer’s gift is verbal as much as pictorial. His modesty is particularly appealing: advised by a well-meaning uncle that he mustn’t put all his eggs in one basket, Feiffer observes that the trouble is he has only one basket and in any case only one egg. Loosely chronological at first, the book becomes more associative in its organisation, leaping from one topic to another. The story is told in a series of vivid, short chapters that are verbal equivalents of the cartoonist’s clearly delineated panel: “Idol” (artist Will Eisner), “Camp Gorgon” (the army), “My Candidate” (a vignette of Democrat Gene McCarthy at the 1968 California presidential primary, preferring to trade lines of poetry with Robert Lowell rather than take a campaign-boosting interview with James Reston), and so on.

Feiffer was a child of the Depression whose parents — Dave (passive) and Rhoda (aggressive) — were genteel-poor, lower-middle-class Jews from the Bronx. A failure academically, he defends himself from the local toughs by chalking up drawings of Popeye bashing up… local toughs, and indulges his secret taste for radio serials and action comic books — the work of Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond and others celebrated in his The Great Comic Book Heroes. (Backing into Forward includes samples of the author’s early work as well as that of his favourite illustrators.)

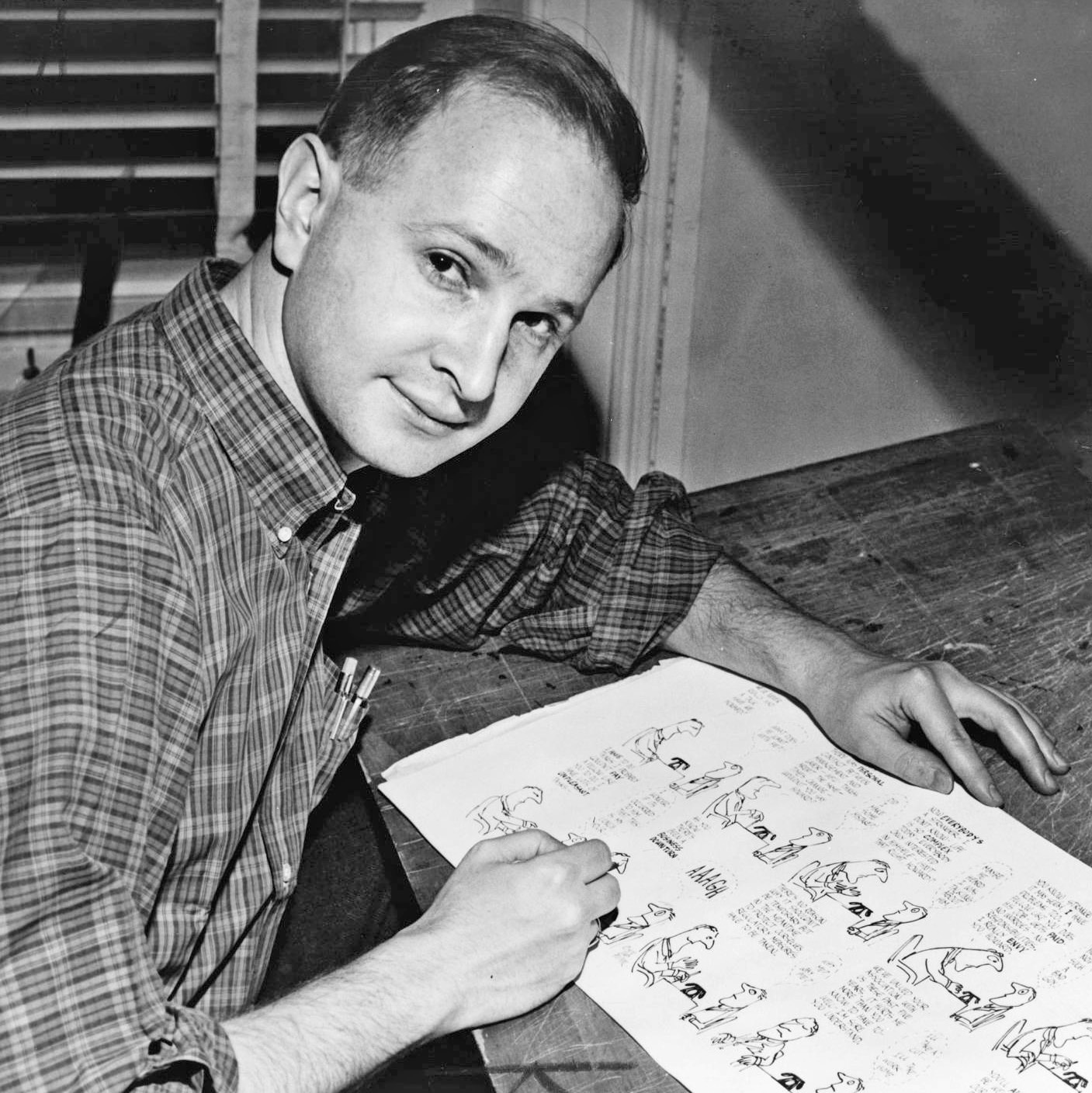

Feiffer by Feiffer, from Backing into Forward.

The politics of Feiffer’s generation were uniformly left-wing: Feiffer’s sister, Mimi, is a Stalinist, Feiffer himself a socialist, and both quarrel with the local Trotskyites. He brings his ideological disposition into the McCarthyite fifties and has some informative tales to tell about the betrayals of playwright Clifford Odets, director and choreographer Jerome Robbins and director Elia Kazan. With no obvious career in sight, he parlays himself into an unpaid “job” as a gofer in Eisner’s studio, where he discovers he can’t draw figures, can’t draw backgrounds, and can’t letter. He does, however, eventually persuade Eisner to let him write the storyline for his comic strip, The Spirit.

There follow some dispiriting years in the army and some equally dispiriting years in an East Village bedsitter, where he struggles unsuccessfully to make his mark in the art departments of advertising studios and magazines, and even in animated cartoons. Finally he presents himself at the Village Voice (then a year old) and repeats the Eisner episode. The editors look at his drawings, inform him that they will publish anything he brings them, but won’t edit him and certainly won’t pay him. They don’t pay him for the next eight years, the years of his astonishing early fame. So ends Part One, “Gunslinger.”

Particularly interesting in Part Two, “Success,” is Feiffer’s account of working on the various productions of Little Murders with Robert Brustein and Elliott Gould (he has his share of failure and rejection, and the chapter on the play is simply titled “Flop”), and with Mike Nichols , Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel on Carnal Knowledge. Here — perhaps inevitably — the story tends towards anecdotes about the great and famous, with whom Feiffer now starts to hobnob. He has his criticisms to make — of Woody Allen’s late-developed taste for “conspicuous shyness,” for example — but he never conceals his wonder at where his talent has taken him. At one dinner party he listens to Kenneth Tynan explain to Marlene Dietrich how he and Ernest Hemingway are no longer on speaking terms. Dietrich shakes her “no-less-beautiful-because-of-the-years-head” and like a very convincing Dietrich imitator huskily croons, “Oh no Ken. No no no, Ken. We can never be mad at Papa.” Ken! Marlene!! Papa!!! Feiffer cannot believe what the boy from 1225 Stratford Avenue, Bronx, is witnessing.

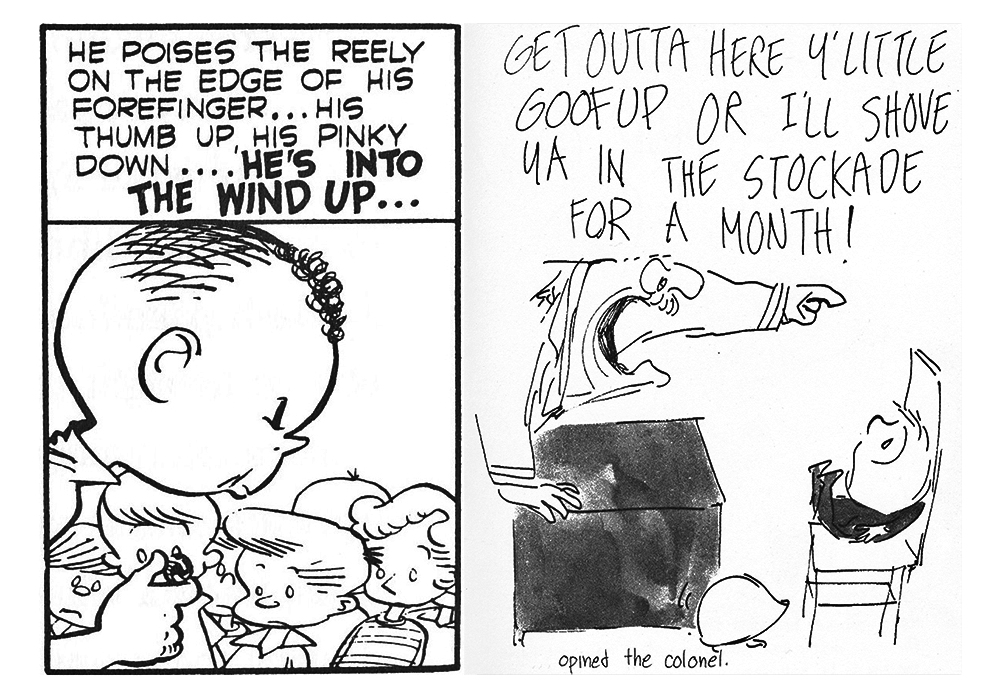

Any artist has to make it new not just in material but in form and Backing into Forward is most interesting in showing from the inside the formal revolution that underpins Feiffer’s work. Simplifying a little one can say that this occurs around 1950–51 with the shift from Clifford to Munro. Clifford was the hero of a comic strip that Eisner allowed Feiffer to draw for the last page of The Spirit lift-out syndicated across US newspapers. Munro was the hero of the first truly Feifferesque comic story, dreamed up during Feiffer’s miserable time in the army in 1951, a story he couldn’t get published for eight years.

Clifford stands somewhere between Pogo and Charlie Brown. That is to say, he is a standardised, cute, lovable child cartoon character of the period. He is delineated in the crisp, professional style favoured by the Eisner studio — deftly inked-in, or brush-flicked, character outlines set against a realistic background. His story is told in a series of nine or so bordered panels with conventional speech bubbles filled with lettering probably done by a lettering specialist and the rapid action-to-action transitions characteristic of the classic comic strip. It is droll, but controlled, conventional and off-the-peg.

Action and reaction: Feiffer’s Clifford (left) and Munro.

Munro, a four-year-old boy drafted into the army, is idiosyncratically and authentically Feiffer. He is drawn in an exhilarating free and informal style that owes something (Feiffer tells us) to the effect on him of seeing the work of Saul Steinberg, William Steig and André François. What Feiffer liked about Steinberg was the cultural critique Steinberg’s art implied (his line “indicted,” he says; it was a form of cultural anthropology); what he liked about Steig (later the author of Shrek), especially the Steig of books like Till Death Do Us Part, was the fusion of Freud, Reich and cartooning; what he liked about François was the careless, improvised, confident freedom of his line:

It was François’s sense of the moment… immediacy on paper… drawing as if it were coming from inside the page out, a scrawl by an invisible hand announcing itself on the page without consciousness of layout, composition or design… art that just happened… that’s what I was after.

It is an apt description of where Feiffer ended up. What he contributed was that overabundance of words — the narrative of inner states of being.

“Munro” represents a complete rejection of Eisner’s cartoon world: both as to draftsmanship (Feiffer comments admiringly on Eisner’s mastery of anatomy, pose, expression, point-of-view, his melodramatic contrast of light and shade, but admits these effects are quite beyond him), and as to subject matter (in Eisner’s case a noirish, melodramatic, quasi-allegorical storyline, for which Feiffer substituted an acute psychological realism).

One gradually comes to see Eisner as Feiffer’s “strong predecessor,” an artistic father figure whom he had to confront, overcome and repudiate. His success depended, as so often, upon a combination of rebellion, self-acceptance, and innovation. Feiffer’s strengths never lay in the direction of his heroes like Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond and Will Eisner: in the tough, disciplined world of professional cartooning Feiffer was a flop and he had to give up his investment in it. He couldn’t even draw a convincing gun; “my guns were made of melting butter,” he confesses. His breakthrough came when he took that melting-butter style, accepted it as his own, and applied it to the depiction of the mid-century unhappy consciousness.

CRUCIAL to Feiffer’s story is the story of his mother, Rhoda Feiffer. Rhoda is the cartoonist’s antagonist in this book; although she has been dead for many years you sense that much of the book is directed to her, that the quarrel, the need to defy, justify, explain and reject is still strong in him. (Dave, gentle, irritable, ineffectual, is dispensable.) Rhoda is affectless, accusatory, dominating, lacking maternal warmth: “Not a hugger, a holder, a kisser, a squeezer, or a pincher. She didn’t go in for bodily contact, certainly not with my father. I’ve suspected for a long time that mine was a virginal birth.” She was, he says, “a control freak… a micromanager who managed ineptly,” who sought some perverse justification for her position by welcoming acts of defiance by others: “endless letdowns, betrayals… weakness on the part of men who left her holding the bag…”

Among many stories of betrayal, Feiffer relates the story of his adored dog, Rex, whom Rhoda gives away to a “fairy tale farmer and his daughter” without telling Jules what she is doing (he is at school when the dog is taken), on the grounds that while the boy might take care of the dog for the moment he will eventually “fall down on the job.” Feiffer remembers the phrase, says that Rhoda “patented it,” and, after all these years, still flinches from its assault.

Feiffer’s sense of his mother’s implacable hostility to her children continues to the end of the book. In Feiffer’s account she engineers her own death with one eye on how it will affect her children: “It was her breath. I believe she was driven to hold it. ‘I’ll show you, I’ll hold my breath till I die.’” She did show us. ‘I’ll die and then you’ll be sorry!’ She died. We weren’t sorry.” Near the front of the book is a cabinet photograph of Jules, aged nine, a beautiful, adored child — but we see the photograph has been folded, torn, and ripped: we can only guess at the history of that disfigurement, and guess too at the circumstances of the photograph’s rescue.

Rhoda’s sad story is a Depression-era counterpoint to her son’s Age of Affluence success. The child of immigrant Jews who settled in the mid-West, she returns to New York conscious of her superiority to the shtetl Jews around her — unlike them, unlike Dave, the third-best man she settles for as a husband in the name of security, a man who mixes up his double-u’s and vees, she speaks in a perfect “accentless English.” Rhoda has talent, artistic taste, ambition. She hopes to succeed as a fashion stylist, a term she believes she invented. Her aim is to get her designs adopted by dress manufacturers, and when Jules sets off on a coming-of-age trek across America he travels with samples of her designs in his rucksack to show to dress manufacturers en route. They throw him out and copy the designs. Success eludes her. All that remains is her resentment, her sense of entitlement, her fierce ambition, qualities that Jules himself, for all his nebbishness, his hatred of his mother, has inherited, along with her artistic talent.

What else drives him to present himself, unannounced and barely nineteen years old, at the door of Eisner’s studio to ask for a job? To work for Eisner just as, later, he works for the Village Voice, for no pay? In both cases he is convinced he has something — something — to offer, not as the inheritor of Eisner but as the founder of a new comic style. This could be presented heroically of course, but more modestly, alert to the role of accident, chance and contingency in even the most driven personality, it is for him just “lucking into the zeitgeist,” or the “backing into forward” of his title.

Rhoda is a monster, and a late chapter details a truly astonishing incident late in her life concerning Feiffer’s younger sister, Alice. But she is also the book’s tragic, unlovable, off-stage anti-heroine, her fall the counterweight to her son’s rise, and for that son, you feel, a piece of unfinished, and unfinishable, business. The stories of Jules and Rhoda go together and give the memoir a satisfying if discomforting coherency — negative space again — and exemplify, comically, tragically, triumphantly, D.H. Lawrence’s observation about the huge mountain of failure that American success is built on. •

Backing into Forward

By Jules Feiffer | University of Chicago Press | $89.99 | 456 pages