Donald Trump’s second term is going no better than his first. He has failed to end the war in Ukraine, failed to put forward a plan on healthcare, and failed to cut government spending. Inflation is higher, unemployment is up and GDP growth has fallen.

His main achievements have been to give tax breaks to the rich (again), adding to America’s debt problems; set off a wave of brutal raids on migrants across US cities; and create an arbitrary tariff regime leading to endless trade war negotiations while raising prices for consumers. His international escapades — including a belated and shaky Middle East ceasefire — are of little interest to the American public.

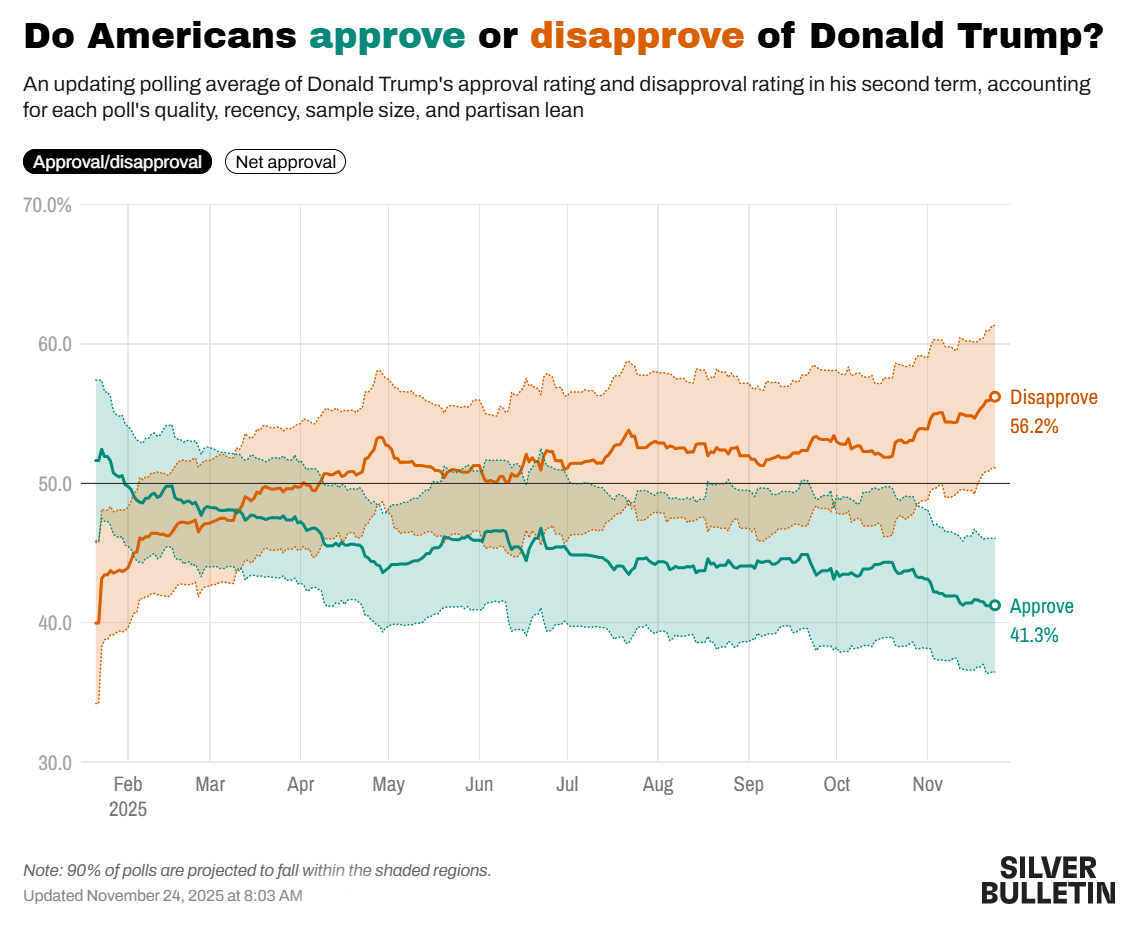

Unsurprisingly, given this record, he is unpopular. His approval rating has dropped to minus 15 per cent, mirroring the fall during his first term. It is negative in thirty-nine states, including all swing states.

Polls aggregation by Nate Silver/Silver Bulletin

Trump’s support has fallen particularly sharply with young people and minorities. Much reporting of last year’s election focused on the “realignment” of these groups away from the Democrats. But they have quickly reverted back. The president’s approval rating on every single issue bar border security is net negative, and is minus 33 per cent on the critical issue of prices and inflation.

This frustration with cost increases led to a dire set of election results for the Republicans at the start of the month. Voters whose main issue was the economy strongly backed the Democrats — a big switch since last year. They won everywhere — taking back the Virginia governorship with a fifteen-point win; defeating attempts to unseat liberal supreme court judges in the critical swing state of Pennsylvania by more than twenty points; and winning their first non-federal statewide election in Georgia since 2006 by the same margin.

This needn’t be existential for the Republicans. It’s not unusual for parties to do badly after winning a presidential election and they tend to start distancing themselves from unpopular presidents, especially second term ones. But with Trump, they’ve gone all in, sacrificing any sense of independence on the MAGA altar. While many have plenty of criticisms of Trump in private they have so far seen the threat of retribution as more dangerous than unpopularity by association.

At the margins we’re starting to see this attitude shift slightly as the midterms come into view. Four House Republicans signed the petition to release the Epstein files, which forced Trump to admit defeat and agree to their publication. One of the signatories — the formerly uber-MAGA Marjorie Taylor Greene — has had a very public falling out with the president, leading to her resigning from Congress. Elsewhere, Republicans in several states are refusing to support efforts to gerrymander seats ahead of the midterms. Indiana is proving particularly resistant, despite a series of escalating threats from the president.

None of this means that Trump’s coalition is about to collapse, or that he won’t be able to do an enormous amount of damage over the coming years. He still has immense loyalty from his base, and people are still scared of him. But a growing numbers of Republicans are realising they’re in serious trouble and frustration is growing. The longer the party is a personality cult, the harder it will be to emerge from his shadow.

In the rest of this article I’ll look at why Trump’s ratings are likely to keep deteriorating; the faultlines this is exposing in his party; what it means for the midterms — including an early look at the key races — and the next presidential election; and why the Republican Party is looking increasingly trapped.

The cost of living problem isn’t going away

At first glance, the level of Americans’ anger over prices seems surprising. Inflation has gone up to 3 per cent from 2.7 per cent at the election last year, after dipping at the start of 2025, but is far lower than the 2022–23 post-Ukraine invasion spike that did for Joe Biden.

Part of the issue is that the earlier inflationary rise is baked in. Prices are going up slower than before but are still rising from what feels like a high base to consumers. Many voters had the impression that Trump would bring prices down, though that was never plausible. Additionally, some critical expenses — including housing — are rising more than the average. Health insurance is also going up well beyond inflation due to rising medical costs.

That’s a particularly critical issue for the Republicans because Obamacare subsidies are about to run out. These help the twenty-four million Americans paying for insurance via that route — and if they disappear premiums will double in cost. The Democrats have made this their big issue, and many Republicans are extremely worried about the political consequences. But so far there isn’t agreement within the party on a plan to extend the subsidies. Nor is there time to replace them with an alternative means of support.

This highlights a broader problem for the GOP. Historically their coalition skewed towards higher-income voters, but that wasn’t true in 2024 — Trump won the poorest third of voters and saw his biggest gains in the counties with the highest rates of poverty. In the past the party could follow its ideological instincts and reduce welfare entitlements to pay for tax cuts without doing too much harm to their own voters. That’s no longer true.

We saw this when food assistance for forty-two million Americans (known as SNAP) was temporarily halted during the recent government shutdown. Despite Trump’s assertion that it was a Democrat problem, he was hurting a lot of his own voters. Though these benefits have restarted there will be long-term damage from the party’s willingness to let families go hungry.

On top of this the US economy is suffering from the twin effects of Trump’s tariffs and crackdown on immigration. So far estimates suggest tariffs have added around half a point to inflation but this could rise as suppliers’ stockpiles of pre-tariff imports diminish and more of the cost increase is passed on to consumers. Concern amongst Republicans about the impact led to Trump removing tariffs from 100 food products — most of which can’t be grown at scale in the US — but notably included beef, which has rocketed in price this year.

Reductions in immigration risk a potentially even bigger hit to the economy. One study estimates reduced inflow and disruptions from fear of ICE will reduce GDP growth by half a point this year. The long-term effects could be much greater. Because undocumented migrants are so important to the agricultural and construction sectors, ICE causing extreme disruption in places it’s focusing on. Another study from California found a “20–40 per cent reduction in the agricultural workforce, leading to $3–7 billion in crop losses and a 5–12 per cent increase in produce prices” following ICE raids. Meanwhile, international enrolment at US universities has fallen by 17 per cent.

Alongside these policies that are deliberately harming the economy there is the question of whether the US’s AI-driven growth will continue. The rise in US stocks since 2022 has come almost entirely from tech companies, with spending on data centres and other infrastructure has offset falls in investment elsewhere. If, as many think, we’re looking at a bubble not far off bursting that could have a very serious impact on the economy (not just in the US). Either way it’s hard to see a resolution to Americans concerns about living costs, and easy to see plenty of ways things could get worse.

Faultlines

It’s the economy that’s causing the Republicans problems for now. There are, though, other faultlines in their coalition. They’ve always been there but have been submerged beneath the Trump personality cult. His unique ideological flexibility allowed him to manage disagreements and the need to show fealty meant people largely followed whatever line he picked. As his power slowly starts to fade they will become more prominent.

One obvious split is around the US’s international role. True “America Firsters” like Taylor Greene are frustrated by Trump’s focus on international diplomacy and deals rather than domestic concerns. Notably, quite a few congressmen and women went on the record after this month’s elections to suggest, cautiously, that the White House might want to pay more attention to the cost of living. J.D. Vance released a similar statement, carefully praising his boss’s achievements while adding that “we need to focus on the home front.”

Trump isn’t going to change his behaviour — dealmaking (or the illusion of such) is what he enjoys most about the job and he’s been meeting a stream of foreign leaders over the past few weeks as well as trying to restart negotiations with Russia and Ukraine. As the party looks beyond him for 2028 candidates, though, it’s likely to prove a divisive topic. Plenty of senators and grandees still see the US’s ability to project international power as critical (as debates about the proposed Ukraine plan have highlighted in the past week). One can imagine the issue being important in, say, a Vance versus Marco Rubio contest for the nomination.

Then there’s the growing rift between the more culturally extreme elements of the MAGA coalition and those who still have some sense of where the mainstream might be. The problem was exposed recently when Tucker Carlson gave a softball interview to Nick Fuentes, an avowed racist and antisemite who regularly attacks “organised Jewry.” While the bulk of the GOP have been content to let by all sorts of racist behaviour, overt antisemitism is a step too far for some. One of the main conservative think-tanks — Heritage Foundation — found itself in the middle of a noisy row after its president recorded a video defending Carlson and Fuentes.

This isn’t a minor issue. Fuentes is the leader of the “groyper” faction on the right (the name comes from a cartoon about an overweight frog). This is essentially the latest manifestation of the online alt-right that emerged out of 4chan and gamergate in the 2010s, aided by Steve Bannon with a view to helping Trump. It’s prominent among young male Republicans — as revealed by leaked WhatsApp group chats — and is characterised by extreme language and offensiveness, done with so many layers of intent and irony that even the groypers seem unsure what they really mean.

Politically it’s a complete dead-end for the Republicans — a vicious and nihilistic cult that has no meaningful purpose. There has been something of a backlash from conservative figures, but Trump has refused to condemn Carlson and other senior figures have opposed the backlash. It’s a divide that has potential to seriously derail future political campaigns. One can easily imagine Carlson launching a presidential bid, and even Trump endorsing him if he felt it was in his interests. It’s certainly no more ridiculous than a Trump bid seemed back in 2014.

This is all part of the Republicans’ wider problem — one that’s shared with radical right parties around the world. They have defined themselves in opposition to social liberalism but have no ideological coherence, or project, beyond that. That often makes them dependent on a strongman leader, leading to serious problems when he (or she) loses popularity or ages out of office.

Different interest groups who share an aversion to the “professional managerial class” and “woke” are all jumbled together. They’re caught between economic liberalism and autarkic nationalism; ultra-hostility to foreigners and the need for immigrants to power tech industries; AI accelerationists and those wanting to regulate; America First-ism and a desire to exert soft and hard power; groyper inanity and sober religiosity. Without the Trump cult to hold it all together it’s hard to know what’s going to emerge from that mess. And it’s not at all clear that party leaders will be able to hold in check the darkest forces they have allow to fester in their movement.

The midterms

Next year’s elections may well surface more of these tensions. Trump’s low approval ratings mean the Democrats are favourites to take the House next November. In generic party polling they are leading by somewhere between five and fourteen points, depending on which poll you believe. Given how narrow the Republican majority is, it’s not impossible that they’ll lose it before we even get to the elections if a couple more representatives in competitive seats resign or die.

The Republicans have responded to the threat by attempting to gerrymander seats in states they control to maximise their midterms total by shifting strongly Republican areas into seats that are currently Democrat or toss-ups. So far they’ve made limited progress, both because the Democrats have done the same in California (and will likely do so in Virginia) and due to recalcitrant state party officials. A federal court in Texas recently ruled the gerrymander there illegal on the grounds that it was partly done on the basis of race. This will be appealed and may well be overturned but if it isn’t the Republicans will likely be in net negative territory when it comes to re-districting.

A House victory would be enough to cause Trump serious problems. His administration would be flooded with subpoenas and investigations. Legislation would become exceptionally hard. If the Democrats were to take the Senate too, he would also find it much more difficult to make appointments (which are only signed off by that chamber) — something that would be particularly critical if a Supreme Court vacancy were to appear.

But taking the Senate remains a tall order for the Democrats, despite the positive national picture for them. To do so they need to hold all their current seats — including some tricky defences in Georgia, Michigan and New Hampshire — and flip another four. They have two good, albeit by no means certain, chances in North Carolina and Maine. Finding another two will be a challenge.

Trump’s approval, though, has dropped to the point that a bunch of seats are at least contestable, including in Texas, Florida, Ohio, Iowa and Alaska. Early polling in Alaska is particularly promising and the Latino shift away from Trump should help in Texas (though Democrats have been hoping and failing to win there for a long time).

At the moment the Republicans remain favourites to hold the Senate. But if they continue to struggle on the economy and start arguing more among themselves a dramatic loss is plausible. If the Democrats can’t win then they should at least be able to get to forty-nine seats, which would give them a good shot at taking control in 2028, when there will be further winnable contests in North Carolina and Wisconsin.

Beyond the midterms

If the Democrats do win the House then the sense of decline and chaos around Trump will only increase as he gets embroiled in any number of investigations. Discussion will quickly move to prospective presidential candidates.

Normally there would be little a president could do to stop this shift of attention. But because Trump has been so willing to act unconstitutionally, he can use the prospect of running for a third term in an attempt to avoid becoming a lame duck. Given his desperate need to be the centre of attention, it’s hard to believe he will happily accept diminishing power and interest.

As I explained in a recent Q+A, I don’t think he is, ultimately, going to try to run again, and if he did he wouldn’t succeed. Until he rules out the prospect, though, he will make it extremely hard for the Republicans to run a normal selection process because prospective candidates will be nervous about looking like they’re undermining him, and will want his endorsement. At very least he will hold back that endorsement as long as possible — when asked in interviews he tends to talk about there being lots of suitable candidates.

This is problematic for the GOP because a rushed or chaotic contest will be easier for a more extreme candidate to hijack, and will make it harder for potential successors to build their own brand free of Trump. Vance is the strong favourite, partly because there are so few viable candidates. (Rubio is second favourite at 20/1, and Donald Trump Jr is third, which gives a sense of the dearth of options.) But Vance’s approval rating, while not as bad as Trump’s, is negative too. And among Trump’s voters support for him is hardly overwhelming. A recent Politico poll found 35 per cent wanted the vice-president to run in 2028, while 28 per cent said they wanted Trump for a third term. Vance would also have to run on his administration’s economic record.

Whoever is the candidate, they’re going to find it very difficult to manage the ideological conflicts within the party without Trump’s cult, his ability to deflect with humour, or his willingness to shift positions as required — and with the president making life difficult for them whenever it suits him to do so. In all three of his elections Trump has outperformed polling thanks to a pool of supporters who rarely vote and don’t respond to polls. But other Republicans have not benefited from the same boost. Like many of his fellow Senate candidates, Vance underperformed the polls when he narrowly won in Ohio in 2022. There is good reason to think Trump can access a crucial sliver of the electorate that no one else in his party can reach, while alienating wealthier voters they’ve historically relied on.

Given this, and if things keep going badly for the Republicans, there will be growing speculation about how they could rig or steal future elections. I continue to think this is low likelihood. Not because they wouldn’t want to — we know Trump would have no qualms — but because there are no obvious way to do so beyond a full-blown coup, or the Supreme Court deciding to explicitly ignore the direct wording of the constitution.

There will, no doubt, be further attempts to find advantage within the existing system, as per current redistricting efforts, and if results are very close things could get messy. But it is likely elections will be free and fair enough to punish the Republicans for their failure to put up any fight against the Trump cult when they had the chance. •