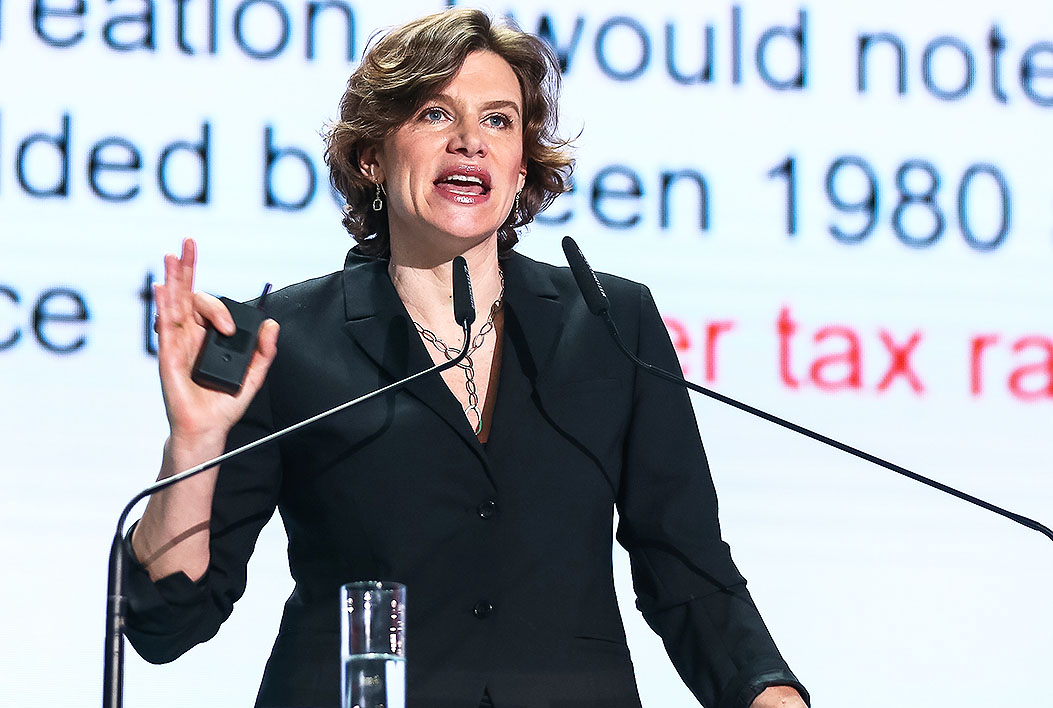

If neoliberalism is dead, what should take its place? In her new book, The Value of Everything, Mariana Mazzucato draws a roadmap to an alternative economic future — one that measures productive activity by the outcomes it generates rather than the money it makes.

In a brave and uncompromising take on the economic developments of the past forty years, Mazzucato calls out the shallow economics that allowed rent-seekers to proliferate and caused policy-makers to lose sight of the public interest. To change our economic system for the better, she says, economists need better tools to distinguish productive from unproductive activity. In other words, we need a new theory of “value.”

Value theory was at the heart of economics when the discipline was born. Adam Smith, writing during the industrial revolution, believed that the value of a commodity comes from the hands that made it — workers. With labour as his starting point, Smith articulated a theory of production, and from there, a theory of economic growth.

David Ricardo expanded on Smith’s ideas to look at the distribution of value across an economy. Holding value theory as the cornerstone of his analysis, Ricardo warned of the dangers of unproductive actors gaining too big a share of the economic pie. Later, Karl Marx built his critique of capitalism directly out of the labour theory of value.

Not long after, value theory fell out of vogue. While it was a useful starting point for our earliest economic thinkers, it was soon discovered the labour theory of value had a fundamental problem — it was impossible to find a general rule to translate the labour-embodied value of a good into a price.

Worse (for many at least), the example of thinkers like Marx and Ricardo showed how one’s theory of economic value informs one’s set of political values. Value theory seemed to undermine the prospect of economics becoming an apolitical, “hard” science.

Modern economics — informed by a school called the marginalists — sidestepped questions of value by defining the worth of a good as the price it can fetch in the market. Today, the economics that gets taught in schools and universities barely mentions value, except superficially — as Mazzucato points out — in terms of “shareholder value,” “value for money” or “adding value.”

But as Mazzucato shows again and again, value-free economic models also have problems. Without a clear idea of what creates value, anything that gets bought and sold on the market is counted as productive. Conversely, any activity that can’t be priced can’t be seen as economically productive.

As a consequence, the new models make it difficult for economists and policy-makers to distinguish economic activity that creates value from activity primarily engaged in value extraction, or rent-seeking. According to Mazzucato, an overemphasis on price risks misidentifying “making” with “taking.”

The book is full of examples of how we’ve got this wrong. Three whole chapters are dedicated to the explosion since 1980 of the finance industry, which Mazzucato sees as more a value extractor than a value creator. And she shows how confusion about value has masked the real story of how value is created. Innovation is mistakenly seen as the result of a few smart inventors tinkering in their sheds, rather than a collaborative and iterative process, often supported by public funds.

The implications are large. Without a strong idea of what sort of activities are productive, policy-makers are at risk of being “captured” by stories of wealth creation. The policies that result (such as tight intellectual property laws) may favour incumbents, inhibit innovation and promote “unproductive” entrepreneurship.

Mazzucato’s book is not a ripping read. It takes a long time to gear up, and it probably could have used a few structural edits. Every chapter is littered with signposts pointing the reader backwards to arguments already used, or forwards with a promise that further explanation is to come. It might have started life as a series of (thoughtful) lectures — I certainly found myself wishing I’d come across Mazzucato’s ideas in the classroom rather than in her prose.

But The Value of Everything has come at exactly the right time. Economics, as a discipline, is suffering an identity crisis. Neoliberalism, the policy doctrine that crystallised an economic framework with no theory of value, is on the way out. Usually associated with free trade, free markets and policies to shrink the size of government, neoliberalism whittled away the power of institutions that shaped the creation of value and the way it was distributed.

Since the global financial crisis, neoliberalism has lost its sheen. Even the old stalwarts of neoliberal development policies, such as the International Monetary Fund, have started to question whether some of its policy prescriptions might have been oversold.

Mazzucato offers a glimpse of an alternative: a framework that puts value back at the heart of economics. Leaving behind the labour theory of the early economists, and moving beyond simply linking of value to prices, she suggests a new way of identifying productive activity: the notion that value comes from actions that promote the sort of economy and society we want.

How to figure out what world we want? That’s an even tougher question. ●