Media Legends: Journalists Who Helped Shape Australia

Edited by Michael Smith & Mark Baker | Wilkinson Publishing | $44

For anyone with ink in their veins (as the expression used to go), even a book with the hyperbolic title Media Legends is an irresistible read, provided it comes – as this volume does – with the subtitle “Journalists Who Helped Shape Australia.”

For yours truly, who was inspired to become a journalist by the legendary exploits of Messrs Woodward and Bernstein four decades ago, the idea of reading about the exploits of characters who always appeared larger than life, and in some cases actually were, takes me back to the days when the impossible took just a little bit longer and all wrongs were writable, because that’s what second editions were for.

The opportunity to participate in momentous events, if only on the periphery of them, was another motive for becoming a reporter. Although I cannot claim to have been under attack in Beijing – as was one of the legends, “Chinese” George Morrison of Geelong via London – every time that familiar video sequence of Bob Hawke at the National Tally Room on the evening of 5 March 1983 comes on the screen it’s reassuring to see the younger, long-haired me behind and to the left of his exulting figure, a confirmation that I was there, a front-row observer of history (and taking notes too!).

None of that or much else qualifies this reviewer for legend status, but it is a sobering thought how many of the modern top-flight journalistic practitioners whose lives are explored in these pages I have had the privilege to meet, and in some cases to know well*, not to mention those chosen to pen their potted biographies.

Through that generation just past, we are introduced to those we were too young to know personally, but heard wondrous tales of. Jack Williams, mid-century press baron of the Herald & Weekly Times, is one of those whose reputation long succeeded him. Well-loved Melbourne columnist Keith Dunstan, whose life story is told by veteran columnist Lawrence Money, related Williams’s keen mental picture of the average reader of the Sun News-Pictorial (as was), which had one of the highest circulations per capita of any morning newspaper in the English-speaking world. Williams told his journalists back in the 60s to keep in mind that the typical Sun reader lived “in a triple-fronted brick veneer in Moorabbin, was married with two children – struggling on a mortgage – and had a mental age of fourteen.”

I recall hearing much the same pep talk given at the Herald Sun when I was subediting in the newsroom there in 2006–07, except that by this time the story’s punchline was crediting the reader with a mental age of twelve. (Perhaps they adjust it after every census?)

The story reminded me of another media legend – one who didn’t make the cut here. Clive Malseed was a rakish (as in spare-framed) pipe-smoking production editor at the Age when I joined the paper at the end of the 1970s. Notably for someone whose job was one of the most stressful on the paper, Clive maintained the most remarkable sangfroid while all around were losing theirs. One of his favourite homilies was to remind us young cadets that, whatever we wrote, it had to make sense to “Mavis Stringbag of Maidstone.”

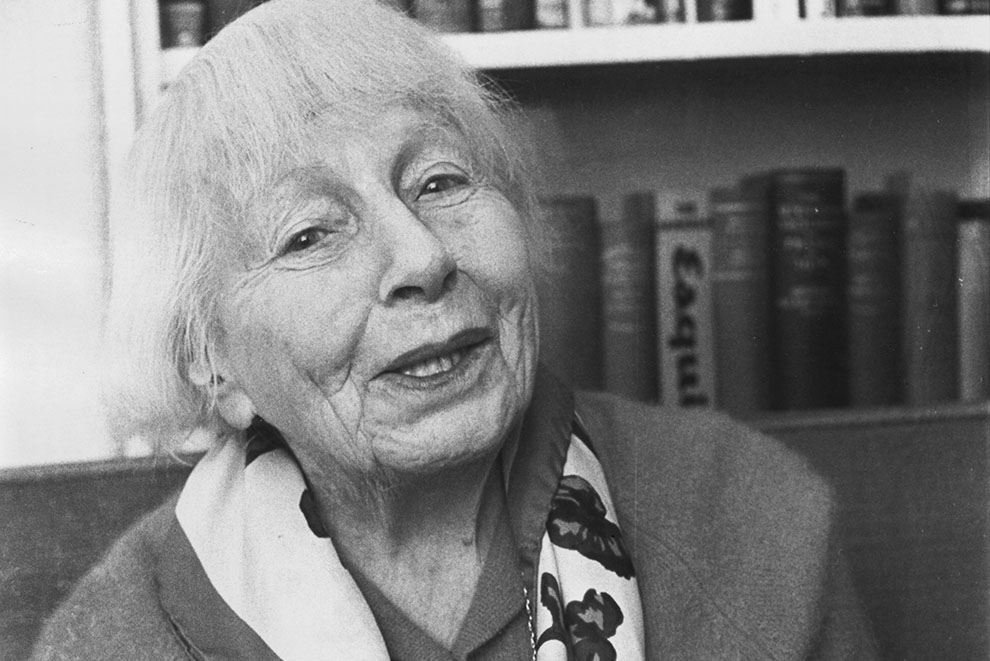

Of course, in a book such as this even the reader with a fair knowledge of “the players” will meet many he or she hasn’t come across before. You don’t have to be a feminist to feel like cheering on May Maxwell, who lived to 101, and had trodden the boards as a soubrette and thespian in her salad days, only to trade the applause for the often thankless career of a journalist in later years. You don’t have to be a feminist to enjoy reading how she took on entrenched arrogance at every turn – but read enough about her and it’s enough to make you one.

For what purports to be – and readers have every right to expect to be – a thoroughly factual record, it is disappointing to come across the odd easily prevented mistake, such as a reference to Ronald Ryan being hanged in 1966 (it was a year later). Sometimes these faults spoil an entire article for the careful reader. When it comes to the inclusion of B.A. Santamaria as a subject in this volume, I fail to see any rationale: he was many things, the éminence grise of the Democratic Labor Party being just one of them; he wasn’t – and I doubt he ever professed to be – a journalist.

But, given that the old shellback’s in the hardback, was it too much to hope that the Labor Split of 1955, which he helped foment, would not appear as “the great ALP split of 1953” (the equivalent of an arithmetic primer instructing us that 3 x 4 = 10) or that he wouldn’t be credited with founding the Catholic Worker Movement in 1957 – making it a trinitarian heresy in toto, given that it was the Catholic Social Studies Movement he had established, a trifling sixteen years earlier.

But such groan-inducing moments are vastly outnumbered by passages of sublime prose. Admire the craft of former Age editor Mike Smith as he weaves a perfect metaphor through this description of investigative reporter Ben Hills’s phone-interviewing technique. Hills would initially disarm his interlocutor with small talk, jokes and flattery. “Then came a series of questions that were the equivalent of slow full tosses on leg stump, luring the victim into playing shots and chancing his arm. Gradually the questions became more relevant, and pointed, including references to facts just conceded… Then came the bouncers, the throat balls and the blood on the pitch. The conversation would end and Ben would curse the corruptness of his prey.”

The schema chosen for deciding where journalists pop up in this work is elegant in its simplicity: the organising principle is the subject’s birth year. The very first entry – with condign justice to the choice, given that he was Melbourne’s first published journalist – is the joint claimant to the title of the city’s founder, John Pascoe Fawkner, born in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

Media Legends, a large-format production of the Melbourne Press Club, comes replete with photographs that add to the atmosphere of every era in which the most talented wordsmiths left their running commentary on the times that shaped them – and, yes, the nation. In an era when the death of newspapers is widely foretold, it is – like former editor of the Times Harry Evans’s My Paper Chase, published five years ago – a glowing tribute to the worldwide empire of newspaperdom which once wrapped its dreams in reality and dropped them on the dewy grass of every front yard in the civilised world six days a week just in time for breakfast.

Like Amazonia, it is a lost world. But books such as this make it easy to go there, wander, linger and return – a round trip encompassing several action-packed lifetimes in the voyage of a single day. Where else could you get such value? •

* Of the book’s twenty-four media subjects still alive, – a former Age reporter and subeditor – was surprised to discover he knows fifteen more or less well. Mr Haley has written this review without fear – but wishes it to be known he wouldn’t be averse to the odd favour.