The timing of US president Joe Biden’s visit to Belfast and Dublin this week could not have been more delicate. The occasion was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, but the trip was as much an exercise in salvaging a peace process that has been teetering for some time.

The fallout of Brexit in 2016 brought an immediate souring of relations between the British and Irish governments, the likes of which had not been seen in decades. More critically, though, it rekindled communal tensions north of the border, culminating in the closure of the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont and the suspension of power sharing in May last year.

Much is now riding on a new British government with Rishi Sunak at the helm, signalling a more pragmatic approach to the Northern Ireland border. The recently negotiated “Windsor framework” for regulating goods crossing the Irish Sea has produced a tentative thaw in relations with the European Union, renewing hopes that Stormont might soon be reopened. Biden’s hastily planned visit was thus a calculated move to tip the balance at a crucial juncture.

His devout Irish Catholic affinities, however, also risked achieving the very opposite by raising the question of whether a presidential visit was the very last thing Ireland — north or south — needed at this time.

At his first and only public engagement in Belfast on Wednesday morning, Biden called on the people of Northern Ireland to leave their history behind and embrace the opportunities of a shared future. “Renewal,” “progress” and “repair” were the dominant themes in a speech that made only scant reference to the divisions of the past.

It was a big ask of a community only just emerging from the “decade of centenaries” — a rapid succession of major anniversaries marking some of the most difficult moments in modern Irish history, from the Ulster crisis of 1912, through the Great War, the struggle for independence, and the fateful partition of Ireland in 1921.

Historian Ian McBride recently said of his country’s acute sensitivity to the weight of history, “We’ve come to believe that dealing with the past or working through the past is somehow good for us.” But it’s only ten years since many people feared that the coming wave of commemorations would be anything but good for the peace process in Northern Ireland. Academics, politicians and community leaders were enlisted to find ways of ensuring that raking over the past would not spark a recrudescence of communal discord.

In the end, the decade of centenaries came and went largely without incident, foreshadowed by a historic visit to Dublin by Queen Elizabeth II — the first of its kind since her grandfather George V in 1911. Even the bedrock enmities evoked by the iconic year 1916 — Dublin’s Easter Rising and the loyalist veneration of the Battle of the Somme — produced few complications when it came to the commemorative program.

But 2016 brought dim tidings of an entirely different kind with the Brexit vote of June that year. Ultimately, it was not the inner workings of Irish memory that tested the mettle of the peace process, but the entirely unforeseen exigencies of a crisis manufactured in England.

An extraordinary inattention to the past was arguably Brexit’s defining characteristic — and its most potent legacy in Ireland. The referendum was notable for the almost complete absence of debate about the possible effects of leaving the European Union on a key plank of the Good Friday Agreement — keeping the Northern Ireland border as invisible as possible. It was one thing to dispense with border checks when both sides were members of the EU single market, but another matter entirely after the imposition of a hard border between the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

Even as these problems came painfully to light in the referendum’s protracted aftermath, advocates of a so-called “hard Brexit” continued to display a callous disregard for the Good Friday Agreement’s brittle compromise. “Softer” options were available to successive Tory governments, but any dilution of Britain’s freedom to chart its own course proved unacceptable to the Brexit ultras. Polling data corroborates this, suggesting that the most passionate leavers were less likely to care about the peace dividend in Northern Ireland.

Biden’s heartfelt message to his hosts — that “for too long, Ireland’s story has been told in the past tense” — somehow failed to capture the issue in all its complexity. Much of the recent turmoil might have been avoided had the past tense — not least the astonishing gains of the last twenty-five years — been given considerably more airplay.

In any event, Biden soon dispensed with his own maxim as he crossed the border into his ancestral home of Carlingford in County Louth. Suddenly, talking “in the past tense” seemed the only thing on the president’s mind in a place that felt “like I’m coming home.” It was as though he had stepped into an entirely different world. The fifty-mile drive from Belfast might as well have been fifty years.

Addressing the Irish parliament in Dublin the following day, Biden notched up eighteen references to “history” and the “past,” reflecting on the “hope and the heartbreak” of his ancestors upon “leaving their beloved homeland to begin their new lives in America.” These stories, he urged, comprised “the very heart of what binds Ireland and America together” — a story of shared “dreams,” “values,” “heritage,” “hopes,” “journeys” and, crucially for Biden, “blood.”

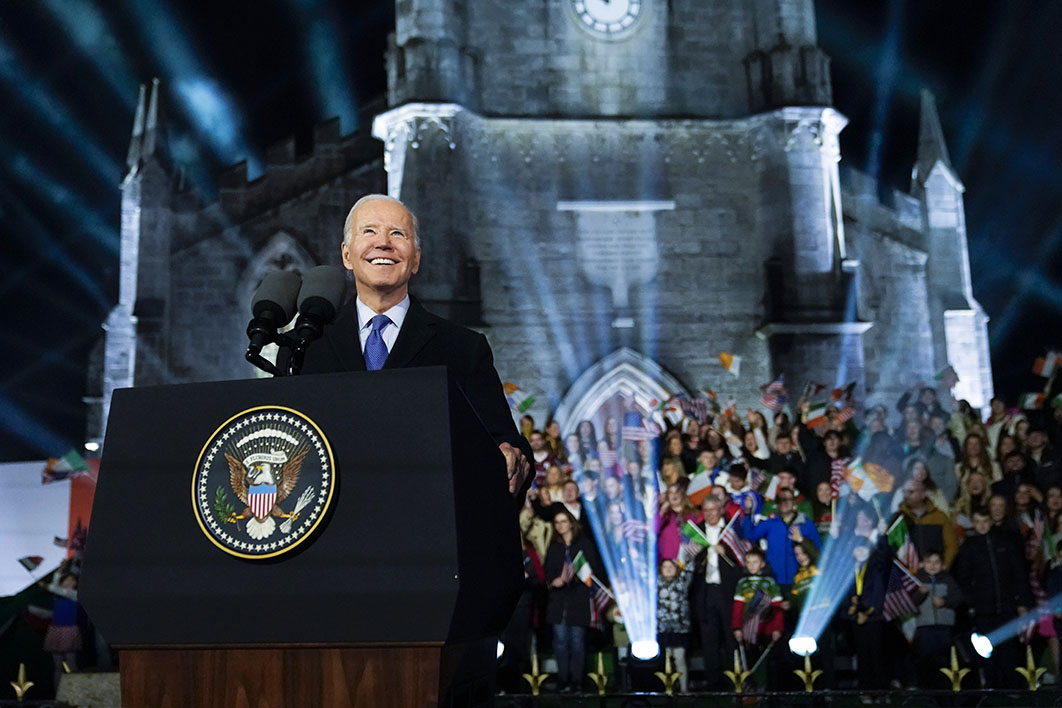

The remainder of his trip was an act of personal homage, flying to County Mayo to visit a family history and genealogical centre before proceeding to the Catholic pilgrimage site of Knock Shrine (the scene of a purported holy apparition in 1879). He rounded off his visit with a major speech to a crowd of some 27,000 outside St Muredach’s Cathedral — another site of deep family significance. “I’ll tell you what,” he assured his audience, “it means the world to me and my entire family to be embraced as Mayo Joe, son of Ballina… the stories of this place have become part of my soul.”

As only the second Catholic president of the United States, Biden rivals John F. Kennedy for the sheer intensity of his identification with his Irish “soul.” As with Kennedy, his Irishness is bound inextricably to his Catholicism, which is why his equally English heritage (on his father’s side) consistently plays second fiddle. Moreover, it is a memory of Ireland rooted in a bygone age — “that fusion of ethnicity and religion,” as Fintan O’Toole puts it, “that has lost much of its grip on the homeland.”

Conspicuously, it is also an Irishness aligned with the very atavisms that the Good Friday Agreement was meant to transcend. Biden’s uncorked nostalgia for his family ties can be irresistibly endearing in its simplicity and humble authenticity. But it also carries unnerving undertones given the tragic consequences of tribal loyalties over the last fifty years.

Little wonder, then, that leading Unionist figures spent much of the week dismissing his credentials as a potential peace broker. Former first minister Arlene Foster was the most forthright in declaring that the president “hates the United Kingdom.” Other Democratic Unionist Party figures concurred that Biden was by far “the most partisan president there has ever been when dealing with Northern Ireland” — suspicions that were only compounded by Biden’s veiled criticism of a UK government that “should be working closer with Ireland” to resolve the wreckage of Brexit.

Though Biden seems largely unaware of the recidivist slant of his Irish colours, he nevertheless understands that his appeal is limited in the North. There would be no reprise of Bill Clinton’s celebrated role in brokering the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The trip itself was cobbled together hastily, at unusually short notice, with an itinerary shrouded in secrecy.

At no stage did the president sit down for direct talks with the key stakeholders or engage directly in problem-solving of any kind. Indeed, the total length of his stay in Belfast was barely sixteen hours (much of it in bed). No press conference ensued from his brief encounter with Rishi Sunak, nor was it possible to deliver his keynote address from the symbolic chair of the Stormont Assembly.

This may have represented a form of political leverage in its own right — holding Sunak and the DUP at arm’s length until they commit fully to implementing the Windsor framework and minimising the disruptions of Brexit. In that sense, the contrasting warmth in Carlingford sent its own clear message.

But if the president had hoped that his mere presence in Northern Ireland might move the dial on a rapid restoration of power sharing, the decision to mix the political with the personal was probably ill-judged. In a week when petrol bombs were hurled at police in Derry by the “New IRA,” he might have chosen instead to prolong his stay in Northern Ireland and leave the family history tour to his retirement. •