Fifty years after Sir Robert Menzies ended his record reign as prime minister, how should Australians remember him? Or rather, how should we imagine him, given that most Australians today are far too young to have any memory of Menzies as prime minister?

Among those who recall that era, Menzies’s legacy remains divisive. Oldies on the right look back in pride and remember a benevolent leader, extraordinarily articulate, able and reliable in running a government, and presiding with wit and wisdom over the nation’s greatest period of economic growth and stability. Oldies on the left look back and remember a smug, old-fashioned relic of the imperial age, “a frozen Edwardian,” as Donald Horne put it, who clung slavishly to what he called our “great and powerful friends” and had the luck to rule Australia while Labor tore itself apart over communism and nearly the whole world was enjoying economic growth and stability.

Both perspectives are aired in a superb two-part documentary, Howard on Menzies, presented by John Howard, our second-longest serving prime minister, to be shown on ABC television this Sunday night and the next. Whatever your perspective on Menzies, if you have any interest in Australia in the 1950s and 60s, I urge you to watch it. It is compelling viewing.

It is not just about Menzies, but also about his times. As you watch it, you’ll feel nostalgia growing for the FE Holdens, the simple frocks and the men’s grey hats, the male companionship of the pub and bowling club, the Spartan but adequate homes where the family crowded around a little dining table: a world that seems markedly poorer than ours, but perhaps happier, and certainly one in which people shared more in common than we do now.

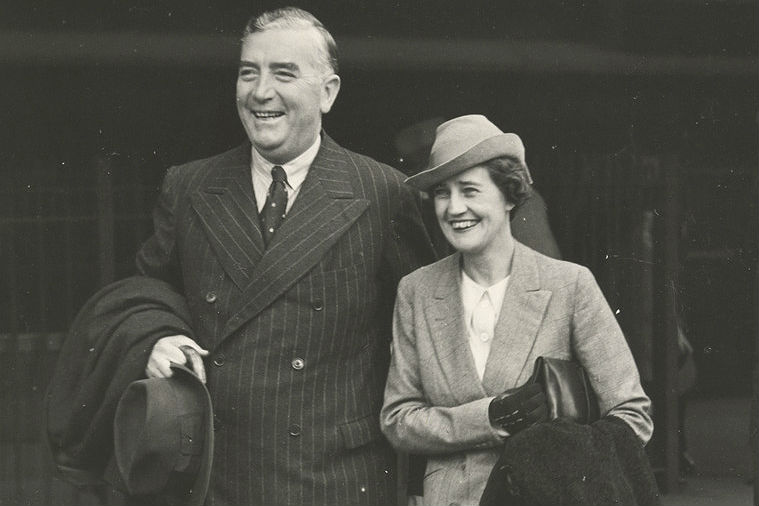

Menzies’s home movies play a big role, as do the newsreels of that age. We see The Lodge as it was then, as Menzies’s daughter Heather Henderson recalls it, surrounded by just “a two-wire fence” and paddocks open to the world. We see Menzies in full flight on the campaign trail, and Mrs Petrov, whose diplomat husband had famously defected, being hustled by Soviet agents up the stairs to a Moscow-bound plane as protestors pushed the stairway away. And, of course, we see the Queen gulping in embarrassment at Menzies’s extravagant public flattery.

Howard idolises Menzies, as he showed in his 660-page The Menzies Era, a hagiography on an epic scale. But the film is better than the book. Director/writer Simon Nasht persuaded Howard to interview dozens of other eminent Australians with different views – to name a few, Bob Hawke, Barry Jones, Thomas Keneally, Bob Gregory, Geoffrey Blainey, Judith Brett, and two of Howard’s fellow students at Sydney University in the Menzies years, Clive James and (former justice) Michael Kirby. They share the narrative with Howard, and it works well – with unusual warmth when Howard is together with his old uni mates.

The ensemble still has Howard’s voice at the centre of it, and its judgements sometimes err on the side of kindness to the great man; we’ll come back to that. But Howard on Menzies is a powerful answer to the question Noel Pearson posed so memorably at Gough Whitlam’s funeral: “What did this Roman ever do for us?”

It is a real question, because much that Menzies did and stood for has little relevance to Australia today. He was a firm believer in white Australia. He was devoted to an ideal of Britain and our British heritage that was outdated in his own time. His government was strongly protectionist and ran a heavily regulated economy. He exuded a charming but old-fashioned paternalism. He had little or no interest in Asia, nor in Aboriginal Australians. He mostly governed Australia well, but he was a cautious reformer, who left a huge backlog of reforms for future governments to tackle.

A second problem with judging him now is that much that made Menzies stand out reflected the times. In an age when politics was fought out in town hall meetings and street rallies, Menzies was one of the great platform speakers. He had a marvellous voice, mellifluous and cultivated, rich in inflections, which he used with fluent irony and persuasive force. I went to his election meetings as a child; the back of the hall was full of rough men screaming abuse at him, which Menzies would ignore until one gave him the opening for a flash of wit at their expense, which he executed like a batsman leaning back and cutting the ball to the boundary. Whitlam almost matched him as a speaker, but Menzies was more eloquent, less overstated, more humorous. Some of that is on show in Howard on Menzies. Unfortunately, such artistry dies with the artist.

It was easier to define Whitlam’s legacy, because most of it went into carrying out reforms and creating policies and institutions we live with today: Medicare, equal pay for women, no-fault divorce, extensive funding for the arts, Aboriginal land rights, welfare for single mothers, an Australian honours system and, not least, large-scale immigration from Asia. Whitlam’s whirlwind three years in power saw more lasting reforms than Menzies’s leisurely seventeen. By and large, Menzies was not focused on reforming Australia but on governing it. He took Australia as he inherited it from Labor, changed a little, but basically concentrated on making good decisions on each issue that came before him. That is harder for posterity to appreciate, because there is less in it for us.

Perhaps his most important skill was his ability as a leader. As Alan Renouf, who served as head of the Department of Foreign Affairs under Whitlam, remarked, “He knew how to manage and lead a team, the rarest quality in Australian prime ministers.”

John Howard presents a more ambitious view. Howard on Menzies tells us that Menzies was the leader who “built the foundations of modern Australia.” And as you would expect, Howard presents a good case, and it makes for absorbing viewing.

Like Howard, like Malcolm Turnbull, Menzies achieved his greatest political success after being dumped by his own side – in his case, in the depths of war in 1941 after his arrogance and abrasive manner alienated his own supporters. In an amusing interview, Howard and Turnbull concur that Menzies reflected deeply on that rejection, and showed great resilience in acquiring the people skills he had lacked (my words, not theirs). Then he reclaimed the leadership, reforged the Liberal Party from the splintered groups of conservatives, gave it a modern social philosophy and led it to victory in the 1949 election.

Howard highlights fairly that Menzies was helped by Labor prime minister Ben Chifley, who misread the mood of the postwar electorate when he unsuccessfully tried to nationalise the banks (a move ruled unconstitutional by the courts) and maintained petrol rationing in a country where more and more families were acquiring their first car.

Menzies was a man in tune with his times. From the backbench, he prepared for the prime ministership through a series of weekly radio talks in which he defined middle-class Australians as “the forgotten people” in a world where unions looked after the workers and the rich looked after themselves. Restored to Australia’s collective memory by Judith Brett’s book Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People, there has never been a better exposition of what the Liberal Party stands for.

So far, so good. But Howard then makes a more contentious claim. Menzies, he tells us, “launches an era of prosperity” which was to last Australia for a generation. The cameras show us FX Holdens rolling off the production line, workers building the Snowy Mountains hydroelectricity scheme, migrants in their thousands stepping down the gangplanks, new suburbs of red-roofed houses springing up, and shopping streets bustling with people. A bit later, Howard adds as a footnote that actually the Chifley government initiated some of this change, yet his argument that Menzies launched the era of prosperity is central to his case.

But it’s not true. First, because the FX Holden, the Snowy Mountains scheme and mass immigration were all Labor initiatives. Menzies inherited them, and had the good sense to keep them running. He did set about building up home ownership, through cheap housing loans, because he saw it as a way of expanding the middle class. In his time, home ownership rates soared from 54 per cent to almost 70 per cent. He would be appalled to see how the party he led is driving down home ownership rates through its excessive tax breaks to landlords. Even Howard, as he watches an auction today, notes that the average house price in Sydney has risen from four times the average income in Menzies’s time to twelve times the average income now.

Second, as Bob Hawke reminds Howard, Menzies was not really interested in economics. He left that to his strong right arm, John McEwen, the trade and industry minister, to his treasurer (at first Artie Fadden, then Harold Holt), and to the experts he inherited from Labor, the “seven dwarves” of senior public servants including such figures as Roland Wilson, his treasury secretary; H.C. “Nugget” Coombs, who ran the central bank; and John Crawford, head of the trade department. Menzies shouldn’t be given credit for the successes of that period or blamed for its failures – including the 1961 recession which almost cost him government. He focused on what he was good at, and he trusted others to keep the engines running in the areas they were good at.

Despite some slips, the Menzies era was a golden period for Australia’s economy. For a quarter of a century, the economy grew by almost 5 per cent a year, unemployment averaged less than 2 per cent, and real per capita income almost doubled. But that was not just Australia’s experience: the 1950s and 60s were an era of global expansion unparalleled in human history, and we were part of that.

To his credit, Howard doesn’t gloss over the fact that this was an era of relatively high protection of industry, centralised wage-fixing, quantitative controls on bank lending, and widespread economic regulation: all things with which his hero was perfectly comfortable, but which are anathema to Howard’s own thinking. He points out that centralised wage-fixing and controls on bank lending gave the government useful additional levers to help manage the economy.

He could also have pointed out that McEwen’s protectionist policies gave certainty to investors, and Australia was rewarded with big flows of foreign investment in manufacturing, which generated higher productivity and higher incomes. And that in Menzies’s time, unlike any time in the past thirty-five years of economic reforms, Australia paid its way in the world, regularly running up trade surpluses to balance the foreign investment flooding in.

Menzies himself listed two other areas as among his proudest achievements: the expansion of university education and the development of Canberra. Commonwealth funding for universities was his initiative, and it transformed the scale of tertiary education in Australia, creating a new generation of universities, including Monash, Macquarie, Griffith and Flinders, and making the Australian National University a research institution of global eminence.

Canberra was an unloved, undeveloped little town until Menzies set about transforming it into a real national capital. Other Australians complained that this indulgent father gave his spoilt child fine schools, excellent roads and beautiful suburbs while other Australians did without. Much of the public service was still in Melbourne in 1950; it was Menzies who set about gradually bringing it all together in one place.

Howard deals with the politics of the Menzies era well. In 1951 Menzies fought and won another election against an increasingly sick Chifley, who died weeks later. The Korean war pushed export prices to record levels, inflation hit 20 per cent, and officials slammed the brakes on hard; an election then would have seen his government turfed out. But by the time the election arrived in 1954, the economy had righted itself, and Petrov’s defection – and his claim that there were Soviet agents on Evatt’s staff – saw Menzies romp home.

Communism was a central issue in the 50s. Communist-led rebellions overseas and strikes at home caused widespread concern not just among Liberals, but also on the Labor side, where Catholic activist B.A. Santamaria led a secret movement within the unions to fight the communists.

The government banned the Communist Party in 1951, only to see the High Court rule its action unconstitutional. It then held a referendum to change the Constitution, but the question failed narrowly. For Menzies, Barry Jones argues, this was a blessing in disguise. “He lost the battle, but he won the war,” he tells Howard. “The Labor Party split over it, which meant he could use it against Labor for the next decade.”

Evatt’s mental health, always suspect, worsened after the Petrov claims. Later in 1954 he turned on Santamaria and tried to ban the industrial groups. Labor eventually split in two, most severely in Victoria. Santamaria’s followers formed the Democratic Labor Party, whose preferences kept the Liberals in office nationally until 1972.

Howard concedes that this made Menzies’s job much easier. “That was a gift of generational dimensions,” he tells us. “But Menzies had to be in a position of trust and strength to exploit it.” Exploit it he did, first against the ruined Evatt, and then against Arthur Calwell when he became Labor leader in 1960.

In the same year, the government ended the quotas McEwen had used to restrict imports, and inflation took off. Alarmed, it slammed on the brakes, then seemed not to notice that unemployment almost quadrupled in a year. At the 1961 election, Menzies got the scare of his life as Labor picked up fifteen seats and got within 120 votes of winning the sixteenth seat, which would have left the House deadlocked. Like a more recent prime minister we all know, he was a little cross on election night. But he got used to having a one-seat majority, and it lasted until he was ready to go to the polls again.

Howard takes us to Goulburn, where the initial election trigger came from a group of Catholic nuns at the Our Lady of Mercy school. Angry that the Labor state government refused to pay for essential repairs to its toilet block, the nuns went on strike and closed the school, forcing the students to flood into government schools. Menzies, already dependent on the Catholic-based DLP, saw his opportunity. He offered Commonwealth funds to repair the toilet block, then followed up by promising to finance new science laboratories in non-government schools, which for decades had received no public funding. State aid became a powerful force pulling Catholics away from their traditional home in the Labor Party. It was the key issue of the 1963 election, at which the government regained a healthy majority.

It was Menzies’s eighth and last election win. His final term was dominated by his decisions to revive compulsory national service and then send Australian troops (including the nashos) to fight against the communists in Vietnam’s civil war. Howard concedes that, in this, Menzies ignored the advice of his experts, but he defends the decision to go to war as (a) essential to retain the loyalty of our protectors, the United States, and (b) worth it because it bought time to shore up democracy in the rest of Southeast Asia.

Hawke will have none of that. He points out to Howard that 521 Australian soldiers died in that conflict, 60,000 Americans and two million Vietnamese. Fifty years later, we are friends and trading partners with the very regime we sent our soldiers to fight. Can’t we ever admit that we made a mistake?

As prime minister, Howard himself repeated that error by sending troops into Iraq. Look where it is now, and ask: what good did we do it, or ourselves? Unlike Menzies in Vietnam, however, Howard was shrewd enough to have the Australians assigned essentially to patrolling duties, not combat. Not one Australian soldier died in combat in Iraq.

The line that the Vietnam war protected democracies in the rest of Southeast Asia is clearly wrong. By the time the US agreed to pull out its forces in 1973, there was not one genuine democracy in Southeast Asia, just dictatorships and the pseudo-democracies of Singapore and Malaysia. And if Australia ever needs the US to protect us, its decision is very unlikely to hinge on whether we followed it into the Vietnam war.

Howard on Menzies treats Menzies kindly on foreign affairs, by far his weakest area. This very clever man at times allowed his emotional attachment to Britain and the United States to override his judgement on what was in Australia’s interests. His futile mission to Egypt on Britain’s behalf during the 1956 Suez crisis was undertaken against the advice of his more knowledgeable foreign minister, Dick Casey, and ended in humiliation. That is dealt with fairly, but the general issue of relations with Asia is not.

Casey’s biographer, W.J. Hudson, drew an important contrast between the two. Casey was not as bright as Menzies, but he had lived much of his life overseas, including stints in Egypt and India, and he had learnt much of value and developed, if not a liking for Asian and Eastern societies, then at least empathy for them and a genuine interest in their progress.

Menzies never lived overseas, and never developed empathy or interest in our giant neighbours. Meg Gurry’s recent book Australia and India: Mapping the Journey 1944–2014 documents the mutual antipathy that developed between him and India’s democratic but neutralist leader, Jawaharlal Nehru. As Walter Crocker, a Menzies supporter and twice high commissioner to India in the 1950s, wrote in his diary in 1955, “Menzies is anti-Asian; particularly anti-Indian; yes, anti-Asian. He just can’t help it.” After hosting a rare visit from Menzies to New Delhi in 1959, Crocker noted sadly: “he didn’t ask a single question about India… He wanted to see none of the sights and he had no curiosity about and no interest in India or Indians.”

That aspect of Menzies is airbrushed out of Howard’s portrait, but it can’t be ignored. He was a man of his time. In many respects, he remained a man of the time he grew up in, in the Edwardian era, when most Australians were racist, when it was our proud boast that the British Empire was so vast that the sun never set on it, and that we were, as he put it, “British to the boot heels.”

The real puzzle is why someone as intelligent, educated and, at times, fearless as Menzies never shed those attitudes he learnt as a child, when so many less clever people around him had moved on to embrace the modern world. Howard on Menzies sheds no light on this.

Howard also overstates Menzies’s role in some of his government’s key initiatives. Menzies was certainly the dominant figure in his ministry, but he ruled Australia with a personal staff of just four people; Howard as prime minister had a staff of forty-four. As a rule, Menzies allowed ministers more freedom to carve out their own agendas than any minister today has – and some of the praise Howard heaps on him belongs elsewhere.

Percy Spender is barely mentioned in the program. Yet as Menzies’s first external affairs minister he was the driving force behind the ANZUS treaty, the Colombo Plan and Australia’s participation in the Korean war – which he pushed through cabinet while Menzies, who at that stage opposed sending troops, was incommunicado on the high seas between London and Washington.

Hawke and Howard rightly praise Menzies for having the political courage to go out and sell a trade agreement with Japan in 1957, just twelve years after the end of the war had left most Australians with a bitter hatred of the Japanese. But Menzies was a late entrant to that battle, which really did change Australia’s future; it was initiated and led by trade minister John McEwen. Twenty years later, Japan, our one-time foe, was buying a third of our exports.

Menzies finally retired in January 1966, aged seventy-one, and moved back to Melbourne, where supporters bought him a house in Haverbrack Avenue, Malvern. (Menzies used to call it “Have-a-look Avenue” because so many people drove past to stickybeak.) A stroke in late 1971 left him incapacitated, and his last years were not happy ones; wisely, Howard does not go into them.

Menzies died in 1978. His funeral was held in Scots Church, and the streets of Melbourne were full of friends and foes alike, recognising that, as Geoffrey Blainey has put it, they had seen a “remarkable political innings. The merits and defects of his policies will always be debated. His towering role in Australian postwar life is beyond dispute.” •

• Earlier articles in our series on the turning points of 1966