This time next month Australia’s immigration policy takes a leap into the unknown. The federal government’s two new regional visas, operating from 16 November, will create significant risks both for the government and for potential visa holders. Take-up could be very low, or — if the numbers meet government expectations — the exploitation of temporary employees could intensify and large numbers of migrants could be left in limbo.

Visas to encourage migrants to settle in regional Australia and smaller cities have existed for around twenty-five years, and at first blush the latest changes seem minor. First, a new regional employer-sponsored visa will replace the current Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme, or RSMS, which has existed since 1995. Second, the provisional state/territory government-sponsored regional visa (subclass 489) will be replaced by a new visa to be called the skilled work regional (provisional) visa.

But the devil is in the detail. Where the old RSMS granted immediate permanent residence subject to a two year employment contract, the new regional employer-sponsored visa will give only provisional status. And while the new state/territory-sponsored skilled work regional (provisional) visa is theoretically easier to access, both will be hard to convert to permanent residence.

Both visas will require their holders to live and work for three years in a regional area or a smaller capital city (Adelaide, Hobart, Canberra and Darwin). Before they can become permanent residents, they will also need to earn a minimum annual salary of $53,400. Provisional employer-sponsored visa holders must also remain in the same occupation for the full three years. For these purposes, occupations are classified according to the six-digit ANZSCO job code used by the home affairs department; even minor changes in work — moving from one type of nursing to another, for instance — could potentially wipe out eligibility for permanent residence.

The existing RSMS visa requires newly arrived workers to enter into a two-year contract with their regional employer, and the existing state/territory-sponsored provisional visa requires them to live in a regional area for at least two years, and to work in that area for a year or more earning at least the minimum full-time wage.

Before we get to the detail of these new visas, it’s worth mentioning that the government is also negotiating additional Designated Area Migration Agreements in a number of regions. These agreements provide opportunities for employers to recruit temporary semiskilled workers with limited English and on very low pay. Meatworkers, farm hands, waiters, cooks and truck drivers are likely occupations. These visas are not counted as part of the permanent migration program.

In effect, these agreements outsource to local and regional authorities the federal government’s responsibility to protect workers from exploitation. Because of their low skill levels and generally poor English, these workers have very little chance of gaining provisional or permanent residence, and most will be required to leave Australia at the end of their temporary visa. In this sense, they are totally beholden to their employers. If they are dismissed, some of them — having spent many years working and living in regional Australia — may become overstayers who are at even greater risk of exploitation.

Designated Area Migration Agreements are poor public policy. By making temporary migrants wholly reliant on a single employer, they replicate mistakes in immigration policy made by the United States and countries in Europe, just when those countries are trying to learn from Australia’s experience.

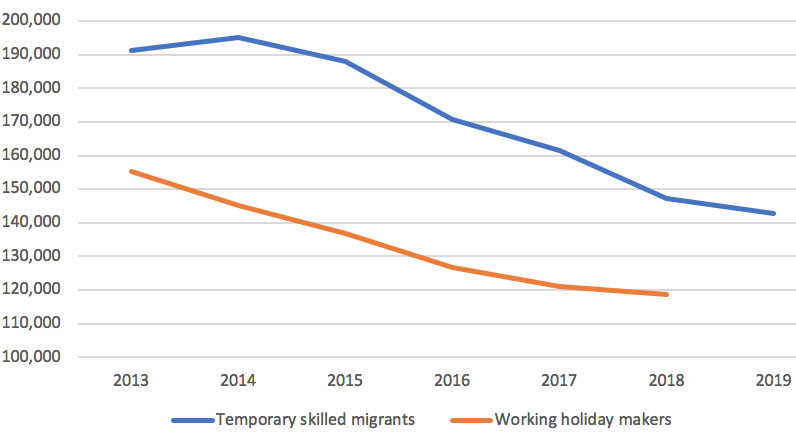

Regional Australia is also feeling the impact of a surge in asylum seekers. The fact that most are working on farms — around 95,000 in recent years — mirrors another feature of failed policy and practice in the United States and Europe. As the chart below shows, the increase in their numbers is being offset by a decline in the stock of working holiday-makers and skilled temporary residents. (None of these people are counted as part of the migration program. But their movements do show up in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’s population figures, which the government can use to reassure business that the migration cuts aren’t as great as they seem.)

Yearly snapshot of skilled temporary entrants and working holiday makers residing in Australia

Source: Department of Home Affairs website. Stock data for working holiday-makers at end June 2019 not publicly available, but first visa grants for these fell significantly in 2018–19.

The government has also set aside 5000 places in the permanent migration program for its new “global talent visa,” which targets people with special skills relevant to niche and emerging industries. Despite the government’s hopes, migration agents advise that take-up of this visa remains low.

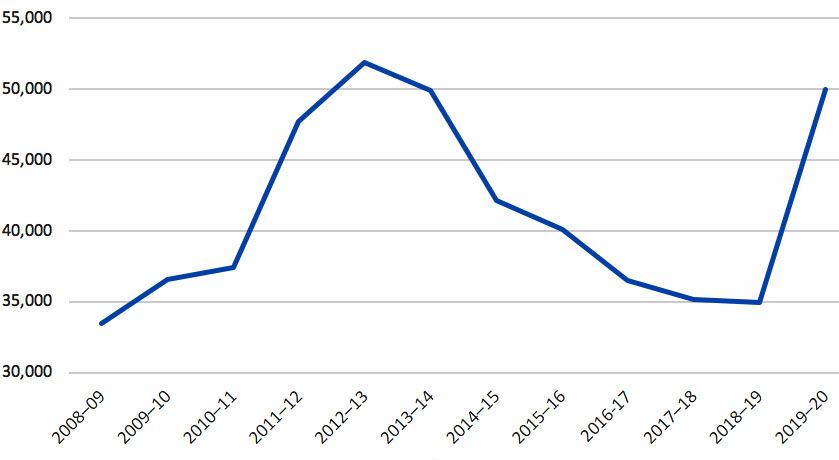

According to the government’s March 2019 population plan, the primary objective of the 2019–20 migration program is to increase the number of skilled people settling in regional Australia while reducing the number who settle in major cities. As this chart shows, the anticipated increase in regional visas is indeed dramatic.

Newly issued state-specific and regional migration visas

Source: Department of Home Affairs migration program reports, 2018–19.

Note: For 2018–19, the chart includes only provisional and permanent residence visas counted as part of the formal migration program. Outcome for 2018-19 does not include a small number of state-sponsored business visas. Designated Area Migration Agreements are not included because they offer no pathway to permanent residence. The 2019–20 planning level includes an assumed 3000 Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme visa grants, but is likely to be less than the actual backlog of applications if there is a surge in RSMS applications ahead of 16 November 2019.

While the overall number of state-specific and regional migration visas planned for 2019–20 may be less than the peak in 2012–13, the risks for individual visa holders are increased by four factors: the speed of the increase in numbers; the relatively subdued demand for labour in regional areas; the increase in the proportion of provisional visas; and the much more difficult conditions for securing permanent residence.

The first challenge, though, will be to issue the planned 50,000 state-specific and regional migration visas in 2019–20.

Demand is strong for permanent residency among the rapidly growing group of temporary graduate visa holders currently in Australia. At the end of June, around 90,000 temporary graduates were resident in Australia, and thousands more had returned to a student visa to acquire additional qualifications and/or acquire the three years of skilled experience required for employer-sponsored permanent visas. Most are living in the major capital cities, of course, but perhaps the federal government thinks that many of them will readily move to regional Australia to apply for the new visas.

The new version of RSMS has 9000 places in 2019–20 to be delivered over seven to eight months — around the same as the number granted for the whole of 2018–19 under the current scheme. Changes made in 2018 have already led to a decline in RSMS application rates so great that a large portion of the 9000 visas granted under RSMS during 2018–19 went to people who had lodged an application under the old rules. The maximum age for applicants was reduced from fifty to forty-five; the English-language requirement was tightened; the minimum required skilled work experience was lifted to three years; and a Skilling Australia Fund charge of $3000 was imposed on small businesses and $5000 on large businesses for each migrant worker nominated. All these conditions carry over into the new version of RSMS.

The new version of RSMS will also require the applicant to undertake a formal skills assessment. No waivers will be available, even if the applicant had undertaken a skills assessment in the process of obtaining a temporary graduate visa after graduating from an Australian educational institution.

Although the new visa will include a larger number of eligible occupations, its various conditions mean that it will be less attractive than a general employer-sponsored visa — the opposite of what the government says it intended. Its 9000 places are unlikely to be filled by a sizeable margin.

Perhaps in recognition of this problem, the federal government is taking steps to limit other options for potential migrants and force more of them to apply for regional visas. Overall, only 30,000 places are available in 2019–20 for employer-sponsored visas (far less than the 40,000 to 50,000 of recent years), and that figure includes any visas granted under the existing RSMS.

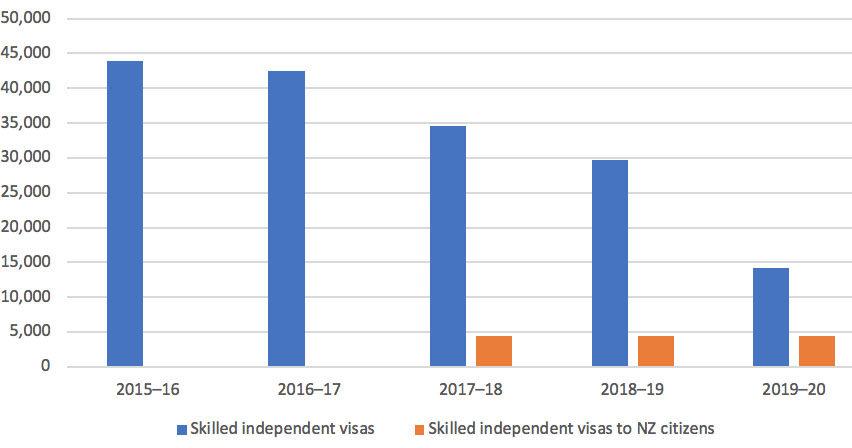

To shift the focus of the migration program to regional Australia, the government has also significantly reduced the number of places in the traditional points-tested skilled independent category, as the chart below highlights. This is the visa category that has most distinguished Australia as a migrant nation over the past thirty years, and has often been approvingly referred to by British and American politicians because of the strong labour-market performance of these migrants.

The decline in these visas in 2019–20 may be even greater than the chart suggests because the government virtually stopped releasing places in this category in August and September this year. If the government persists with this strategy for many more months, it may run out of time to process even the reduced number of places in this category planned for 2019–20.

Newly issued points-tested skilled independent visas

Source: Department of Home Affairs website.

Notes: The figures for 2018–19 and 2019–20, which are projections, assume the same level of skilled independent visas to New Zealand citizens as in 2017–18. Prior to 2017–18, NZ citizens accessing skilled independent visas were not counted as part of the migration program.

These declines in numbers leave state/territory government-nominated visas to play a crucial role in delivering the 2019–20 migration program.

The Commonwealth has planned for 24,986 places in 2019–20 for two of the existing state/territory-nominated visa subclasses — the direct permanent residence subclass 190 as well as the provisional subclass 489 — in 2019–20. During July and August this year, state/territory governments nominated 1130 migrants under subclass 190 and 3197 migrants under subclass 489. In the latter, the Coalition-held states of South Australia (1662 nominations), Tasmania (703) and New South Wales (649) led the way, with very few nominations from the other states/territories.

At that rate, the planning level of 24,986 looks achievable. But once the old subclass 489 is closed to new nominations on 16 November, all state/territory governments will need to significantly increase nominations under subclass 190 compared to the first two months of 2019–20.

Demand for subclass 190 from temporary graduates in Australia will be very strong. But if the labour market weakens further, state/territory governments may choose to severely limit the number of migrants they nominate under subclass 190. That would result in a shortfall in visa grants compared to the 24,986 planning level.

The Commonwealth has allocated a further 14,000 places for the new state/territory-nominated provisional visa starting from 16 November 2019. Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory are likely to use it very sparingly given the possibility of exploitation and the risk that these migrants will be unable to find employment that pays $53,400 per annum over three years. The Labor governments of these states/territories are likely to prefer the subclass 190 visa, which allows for immediate permanent residence — though only for people in the health, aged care and other occupations with critical shortages.

The federal government will be pressuring South Australia and Tasmania in particular to significantly increase the number of migrants they nominate for the new provisional visa. Both governments will be wary of the risk of exploitation and destitution, South Australia especially so given that nominated migrants in that state have in the past complained that they were misled about the ready availability of well-paying skilled jobs.

The key point is that jobs that pay recent graduates $53,400 per annum — the same minimum salary required for skilled temporary entrants in Sydney and Melbourne — are not common in South Australia or Tasmania, or indeed in many parts of regional Australia. This might be a low salary for experienced skilled workers in large cities, but it is too high for relatively recent graduates in regional Australia. (In May this year, average annual earnings for all private sector employees in South Australia were $52,265, and $49,322 in Tasmania. In regional centres — Albury, for example, on $45,382, or Griffith on $41,042 — the figures were even lower.)

In time, of course, most skilled migrants attract much higher salaries. But to expect them to do so soon after graduation puts them at risk of exploitation and/or immigration limbo.

Add to that the high and rising rates of unemployment in these states, and the South Australian and Tasmanian governments would be foolhardy to make extensive use of the new visa. Trend unemployment in South Australia increased from 5.5 per cent to 6.8 per cent over the year to August 2019, with the rate for people looking for full-time work increasing to 7.4 per cent. In Tasmania, trend unemployment increased from 5.9 per cent to 6.6 per cent over the same period, with the rate for people looking for full-time work increasing to 7.3 per cent.

The challenge in South Australia, Tasmania and regional Australia will be to match the skills of potential applicants with the vacancies that do exist (11,500 in South Australia and 3700 in Tasmania as at August 2019). Experience shows that this isn’t straightforward.

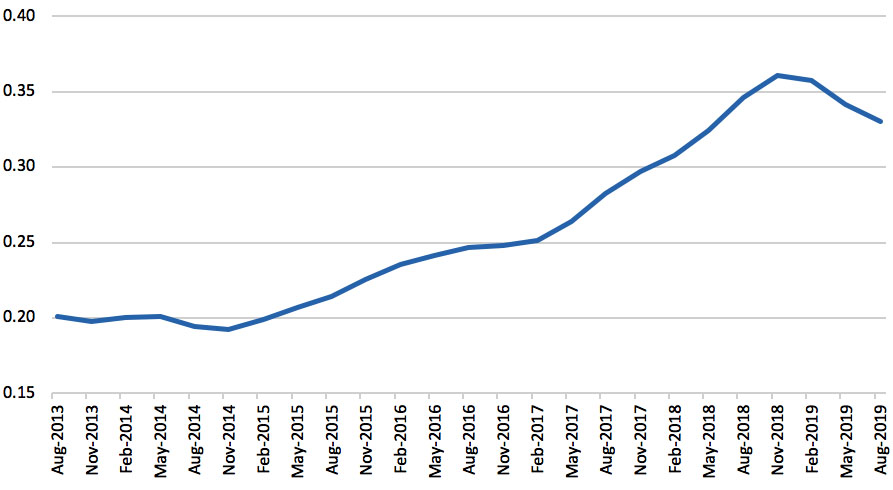

Of course, the largest numbers of job vacancies in August 2019 were in New South Wales (76,200) and Victoria (65,400), and most likely mainly in Sydney and Melbourne. As the next chart shows, while the number of job vacancies has risen strongly as a portion of the number of unemployed in recent years, this trend reversed in 2019. Nevertheless, the overall number of job vacancies remains substantial.

Job vacancies as a proportion of total unemployed

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics catalogue nos. 6202 and 6354.

The government’s skilled migration strategy will do little to tackle these shortages, and cuts to funding for post-school education and training of Australian residents will make them worse. The fact that many overseas students study commerce and finance, occupations that are not in high demand in regional Australia, will also complicate skills matching by state/territory governments.

As it stands, the most likely outcome for the 2019–20 migration program is that the Commonwealth’s skilled migration projections won’t be met without significant policy changes. When the shortfall attracts criticism from the business sector, the government may try to shift the blame to state/territory governments. And to maintain its preferred balance of migrants — two-thirds skilled, one-third families — the Commonwealth might also need to cut back further on the family stream, which would raise a whole fresh set of issues. •